Temperance and tee-total reformers offered another way of changing society and the temperance movement was a major cause of social reform in Victorian Britain. Our ' witnesses ' in the following are The 'Society of Friends', also called Quakers, a Christian group that arose

in mid-17th-century England, dedicated to living in accordance with the ‘Inward Light,’ or direct inward apprehension of God, without creeds, clergy, or other ecclesiastical forms. In this instance, they are on a temperance mission.

The writer, of their journey, is

The writer, of their journey, is

' Shadow ' . We know nothing about Shadow.

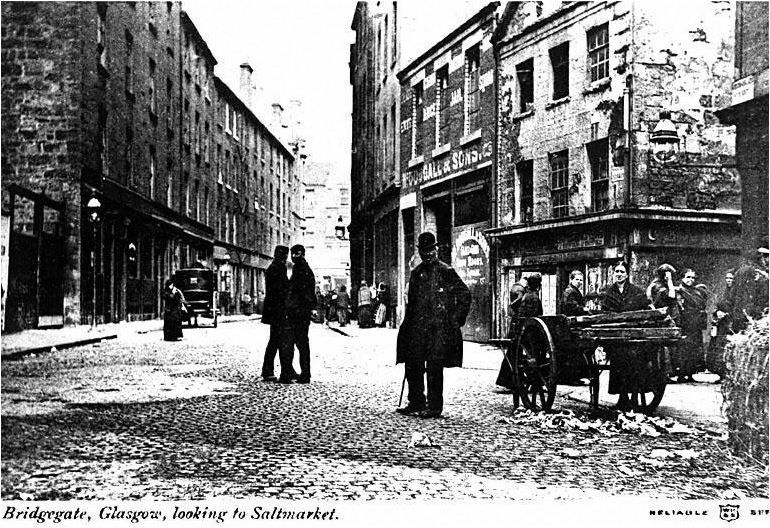

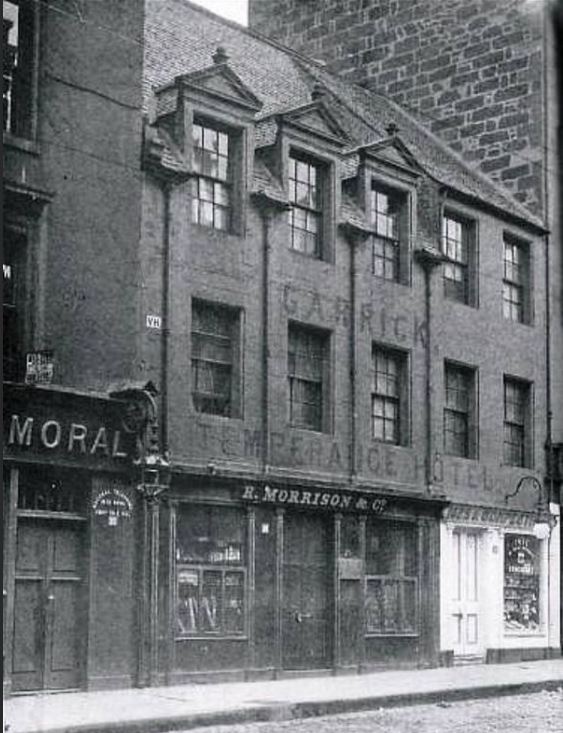

It's Sunday evening and our ' visitors ' have spent the day observing differing church services around Saltmarket, Trongate, Bridgegate areas. These quakers dined at the Garrick temperance Hotel in Stockwell Street before

It's Sunday evening and our ' visitors ' have spent the day observing differing church services around Saltmarket, Trongate, Bridgegate areas. These quakers dined at the Garrick temperance Hotel in Stockwell Street before

continuing their exploration. First stop - Bridgegate or Briggit area of Glasgow.

...Some of the inmates on the second floor also form exceptions to the general squalor and wretchedness. The air of comfort and cleanliness which characterise their homes — each consisting

...Some of the inmates on the second floor also form exceptions to the general squalor and wretchedness. The air of comfort and cleanliness which characterise their homes — each consisting

of but one small room — is particularly noticeable. One household consists of a widow and her two daughters, engaged during the week in factory labour. The eldest girl, as we enter, is busy reading the Bible. Round the walls of the room is a great variety of crosses and

pictures representing the crucifixion, the Virgin Mary, and several of the saints, some of them coloured and in frames, carefully and neatly set ; others, simply small figures in well-polished iron, suspended by a cord from a nail in the wall.

Thoughtlessly forgetting the sensibility of the Catholic, we remark, pointing to the playfulness of the cat, which has mounted the table for its share of observation.

Quitting with pleasurable emotion, the home of these pious people, for it seemed a sort of oasis in this

Quitting with pleasurable emotion, the home of these pious people, for it seemed a sort of oasis in this

moral wilderness, we proceed to visit several houses in another close, all representing more or less wretchedness, vice, and ignorance. In no case, however, do we find any of the inmates the worse of drink.

Their extreme poverty, together with the difficulty of obtaining liquor, seems to render their being so, an impossibility.

- more later -

- more later -

A case of distress particularly arrests our attention. It is that of A Poor blind widow, with three or four young children around her. They live in cellar, within a yard or two of a dung-heap, sending forth its noxious smells, and fever-causing exhalations.

By the uncertain light of a small glimmering fire, we can recognize at a glance the wretchedness of the abode. It reminds us more of a charnel house than a dwelling place for the living. Amid this desolation sits the afflicted widow in her faded tattered tweeds.

Poor woman ! Poor woman ! she has seen " better days" — worse she cannot. Around the hearth are squatted her dirty ragged boys, each tearing from the other a filthy bone picked up in the street. On our expressing surprise at a thing so horrible, she says,

" On aye, sir, they're glad o' ony thing, puir things, but they maun gang to bed." Upon this the youngest of the four — a poor fleshless child of four years old, pale and emaciated — rises, rubs his little eyes, scratches his hands, and shakes himself terribly, as if

suffering from some cutaneous disease. The scene is sadly pitiful. In a corner of the room is their bed of dirty matted straw. Fortunately, a wreck of a bedstead keeps them from the damp floor. We visited this place again at midday, and found that

this " home" was dark as the grave ! God pity us, we exclaimed, — can such things be in a Christian land !?

- more later -

- more later -

''In almost all the other places visited, the children are playing about in back courts, and at the bottom of stairs. In few of the houses are the beds entirely unoccupied. Some of the men are smoking by the fire, or reading a penny newspaper.

The women, such as are well to do, are engaged in cooking. Out of the whole of the families called on, not one of the number, so far as we can learn, has been at church, or is accustomed to attend; the usual excuse being the want of decent apparel. The majority, however, are

Roman Catholics. In many instances, the filthy and crowded state of the apartments is simply indescribable, — there being as many as three and four beds in one room, meant to accommodate male and female, old and young, the sick and the healthy, the living and the dead.''

As we quit the hovels of the Bridgegate, the sonorous sound of the Cross bell proclaims, the hour of Nine.

Trongate, the Saltmarket, High Street, and all within a stone's throw of this once aristocratic vicinage, is literally crowded.

- more later -

Trongate, the Saltmarket, High Street, and all within a stone's throw of this once aristocratic vicinage, is literally crowded.

- more later -

''In almost all the other places visited, the children are playing about in back courts, and at the bottom of stairs. In few of the houses are the beds entirely unoccupied. Some of the men are smoking by the fire, or reading a penny newspaper.

The women, such as are well to do, are engaged in cooking. Out of the whole of the families called on, not one of the number, so far as we can learn, has been at church, or is accustomed to attend; the usual excuse being the want of decent apparel.

The majority, however, are Roman Catholics. In many instances, the filthy and crowded state of the apartments is simply indescribable, — there being as many as three and four beds in one room, meant to accommodate male and female, old and young, the

It's ten o'clock. And making our way towards the Glasgow cross/Trongate we find the locality still crowded with people — and almost every third or fourth shop is open for a long time together — the victualer's shop, the sweet shop, and the low pie shop. Stepping into the

latter, down a small narrow stair, accompanied by our friend before referred to, we are politely shown into an empty box, secreted by a sort of green curtain. Not feeling perfectly satisfied with our quarters, we open a neighbouring apartment, very much to the

displeasure of the landlady, and a company of six or eight boys and girls, about twelve years of age, who sit within, ragged and filthy, and looking as womanly and manly as they can, with a row of ginger-beer bottles set before them, and as many empty plates.

" Beg your pardon !" is our apology, and forthwith return in disgust to our own crib, ordering a couple of pies, which we do not eat.

We next visit some of the lowest lodging houses for " travellers and others " one in particular beggars description. The " close mouth " as usual, is surrounded by a few dirty idle women, the stench almost insufferable.

Proceeding up an outside stair, a window on the left arrests our attention. Several of the squares of glass are broken,their utility partially supplied by bundles of old rags. The light of a small twinkling fire reveals to us the interior of the apartment.

In it are placed two beds, occupied respectively by two men. Round the fire-place is collected a group of rather repulsive-looking women. Utensils with dirty water are scattered about the floor. One or two strings are suspended from wall to wall, over which hang a few articles

of dress. Observing our arrival upon the landing of the first floor, one of the women, in a state of apparent excitement, comes to greet us, " Whit dae ye waant here ?" she asks. " We want the Lodging house,'' we answer. " It's in therr," pointing to one of two or three

doors facing us. And just as we are going to knock, the lodging-house door is opened by a woman of strange appearance, with a brush in one hand and a black cutty pipe in the other. " Weel," she says, in rather a hasty tone, " Whit's yer wish ? "- " Are there any beggars

sleeping here?" we ask. "Beggars! Naw sir; therr's nane but respectable folk sleep wi' me." As the words fall from her lips, we cast an eye round the room — a perfect pig stye, with three beds in it, all occupied by some poor traveller or outcast. " What do you charge

for your beds ? " " Oh, different prices,'' §he replies; " We can gae ye a very nice clean bed for tuppence ; but it depends upon whether you would ha'e onybody to sleep wae ye or no."

''What is the greatest number, now, you ever accommodate in these beds?" we inquire. "

''What is the greatest number, now, you ever accommodate in these beds?" we inquire. "

As many, sometimes, as nine, bit usually six or eight." " Both sexes ?" " Oh, aye, we're no very partiklar."

- more later -

Leaving the good lady and her lodgers to sleep as they best can, we visit three or four other houses in the small wynds that lead off Glasgow cross, containing private families. Suffice it to say, that the scenes are simply dreadful.

Living in a small room, not more than 8 feet by 9 or 10. In it, on a handful or two of straw, scattered in different corners, sleep three poor women. One of them old, blind, and deaf with age. Another confined with a child but twenty-four hours or so before.

She is already up, and commences her work on the mor- row. On the floor, in a corner of the wretched abode, facing the door, lies a bundle of filthy rags. " What is that there ?" we say. " That is my baby," the poor woman smilingly replies, with a pride which a

mother's heart only knows.

" Dear me, you do not mean to say that the poor infant lies there?" "Aye; that is where she wis born, poor wee lamb, an' a sweet child it is," lifting it up and presenting it to us. " Yes, it is," we remark, " a dear, lovely child." But how hard,

" Dear me, you do not mean to say that the poor infant lies there?" "Aye; that is where she wis born, poor wee lamb, an' a sweet child it is," lifting it up and presenting it to us. " Yes, it is," we remark, " a dear, lovely child." But how hard,

we thought, that the poor innocent should be cradled in misfortune ; not even blessed, as we were afterwards told, with the decent dowry of legitimate birth.

A somewhat different scene now comes under our notice. It is that of a tall and gentlemanly-looking man lying

A somewhat different scene now comes under our notice. It is that of a tall and gentlemanly-looking man lying

prostrate upon the ground, close to the Cross Steeple. His head is resting on the pavement in a pool of blood, and his feet and body in the sewer. He lies perfectly senseless. In a moment a crowd of spectators contemplate the horrid sight. The policeman on the beat is

attracted thither. The shrill sound of his whistle calls neighbouring policeman to the spot. " Does any one know about this man ?" inquires the most active of the force. No one replies. Not a word can any one tell respecting him.

To all appearance he is severely injured, and the worse of drink.

- more later -

- more later -

Just as he is being lifted by the watchmen, a little man dressed in fustian jacket and trousers approaches in a state of great excitement, exclaiming, — " Here's the men wha did it," pointing to two black- guard-looking fellows in the hands of two policemen.

The case is forthwith removed to the central office. As we enter, the Lieutenant calls out, — " Hey! what is the matter with you now, man ?" addressing the poor fellow with the broken head. By this time the blood is streaming down over his face, rendering him, with his

great sandy-coloured moustache, and one eye, an object of pitiful disgust. The policeman, on whose beat the tragedy occurred, explains the case, and submits for examination the cowardly ruffians who perpetrated the assault. " Did any one see this man," referring to the

prisoner, " knock the gentleman down?" "I saw him," says the spirited little man in fustian, the only eligible witness in the case ; " and this man too, his companion, saw him knock him down, and then kicked him." The Lieutenant — " Did you see that ?" Witness —

" No, I didn't." Lieutenant — " What, then, did yon see ?" " The man was drunk, and he assaulted us. " Lieutenant — " Aye, that's enough, go away with you, and come here to-morrow morning, and get out your friend." Second Lieutenant — " You're a set o' cowardly scoundrels.

- more later -

That man is well known to us. He is as harmless as a child." The poor fellow, who turns out to be an unfortunate artist given to drink, is taken into a side room, and has his wounds dressed by the surgeon in attendance. While this is being performed, he is curious to know

what he is " in for noo," and what he has done. We were told he lost his eye some months before through a similar encounter.

TWELVE o'clock strikes as we are about to quit the police office, when a reporter from one of the newspapers makes his appearance, wearing a Jim Crow

TWELVE o'clock strikes as we are about to quit the police office, when a reporter from one of the newspapers makes his appearance, wearing a Jim Crow

hat. In an instant, he is inside the bar, as much at home as the night-lieutenant himself, humming in a low tone some favourite ditty picked up at the latest performances of "the Royal" or " Princess's." As the leaves of the Police book — that dark side of

" our civilisation" — are being unceremoniously turned over with one hand, a small eye-glass is made to perform sundry revolutions round a delicately-formed finger of the other. " A case" or two forthwith arrests attention. The pencil is now substituted for the eye-glass,

and in a second it transfers to the pages of a note book, certainly " fearfully and wonderfully made" characters, such paragraphs as " Body Found" — " Alarming Fire" — " Drank and Disorderly," etc. Imagination, for a moment, follows this highly useful and intelligent

functionary to the editor's room, and the printing office. In the former place, " Telegraph !" resounds in the ears of the listener, as a model member of the rising generation, dressed in the Company's livery, casts a bundle of telegrams upon a huge table, already

groaning under a load of newspapers and rejected manuscripts.

-more later-

-more later-

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter