Radical War - Meetings at Meikleriggs Muir, 1819

.

The years following the defeat of Napoleonic France at Waterloo in 1815 were years of hardship for Paisley and the textile manufacturing villages of Renfrewshire. High food prices and recurring bouts of unemployment

.

The years following the defeat of Napoleonic France at Waterloo in 1815 were years of hardship for Paisley and the textile manufacturing villages of Renfrewshire. High food prices and recurring bouts of unemployment

contributed to suffering and distress, particularly among weavers, their families and dependents. In Paisley and elsewhere, demands for a reformed and representative House of Commons, able and willing to address the problems of the industrial areas, were revived and

became more insistent.

On 16th August 1819 at St. Peter's Fields in Manchester, eleven people were killed and hundreds wounded and mounted soldiers, acting on the orders of local magistrates, rode into a densely packed crowd of men, women and children assembled for a

On 16th August 1819 at St. Peter's Fields in Manchester, eleven people were killed and hundreds wounded and mounted soldiers, acting on the orders of local magistrates, rode into a densely packed crowd of men, women and children assembled for a

meeting in support of parliamentary reform. News of the so-called 'Peterloo Massacre' soon reached Paisley, where local reformers were soon at work organising a mass meeting to be held at Meikleriggs Moor, just outside the town, on 11th September.

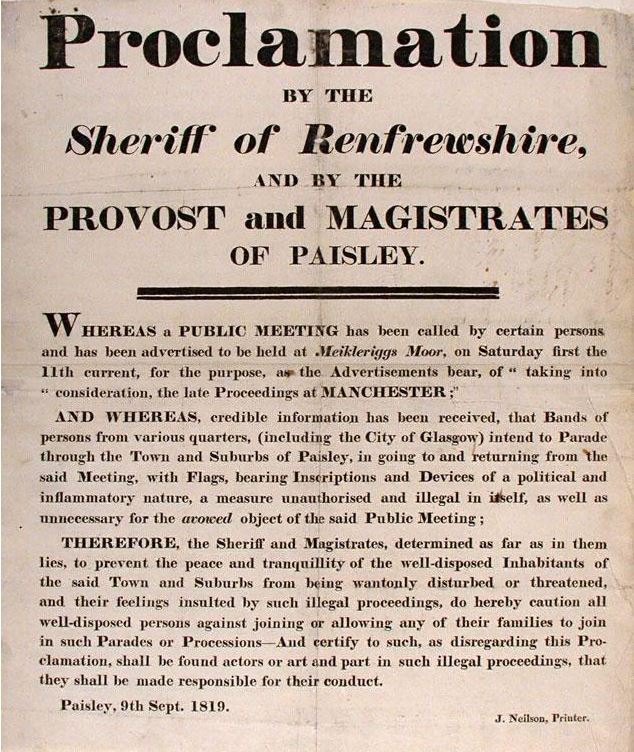

Hearing of the plans of the

Hearing of the plans of the

reformers, the Sheriff of Renfrewshire and Provost and Magistrates of Paisley took steps to ensure that the demonstration should remain peaceful. Notices were posted warning against the carrying of flags bearing political messages, which was considered both

inflammatory and illegal, and local citizens were reminded of their responsibilities in ensuring that peace and tranquility was preserved.

- more to follow -

- more to follow -

Attempts by the authorities to discourage participation in the protest against the Peterloo massacre were unsuccessful. Large numbers of radical reformers and their supporters from the manufacturing towns and villages of Renfrewshire, Ayrshire and Lanarkshire marched

through Paisley and assembled at Meikleriggs Muir as intended on 11 September 1819.

The rally at Meikleriggs passed off peacefully, with the crowds departing in good order in various directions. When a contingent from Glasgow, with banners unfurled in defiance of the

The rally at Meikleriggs passed off peacefully, with the crowds departing in good order in various directions. When a contingent from Glasgow, with banners unfurled in defiance of the

official order, had their banners seized by the Provost at Paisley Cross however, a volley of stones and missiles thrown at the Special Constables heralded a week of rioting.

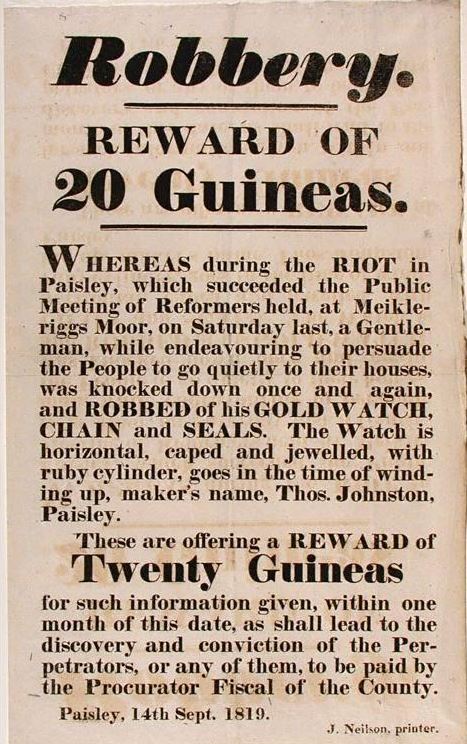

One of the first victims of the disturbances which followed the meeting was a Mr. Burns of Gateside,

One of the first victims of the disturbances which followed the meeting was a Mr. Burns of Gateside,

who visited the Police Office at Paisley Cross to report that he had been assaulted and robbed of his gold watch. Three days later the Procurator Fiscal of Renfrewshire, eager to find out more about those responsible for the disturbances, offered a handsome

Initial attempts to preserve and restore peace in the town depended on the force of volunteer Special Constables enrolled from the ranks of the 'respectable citizens' and first established in1795. Special Constables each carried a baton and the time of the disturbances in

September 1819 the force numbered more than five hundred.

On Saturday 11th September, the first day of the riots, it soon became clear that the Special Constables alone were unable to clear the streets of stone-throwing mobs which appeared in various parts of the town.

On Saturday 11th September, the first day of the riots, it soon became clear that the Special Constables alone were unable to clear the streets of stone-throwing mobs which appeared in various parts of the town.

Cavalry were summoned from Glasgow to assist and found themselves busily engaged for much of the following week. On Monday night the situation was so serious that two Companies of Infantry were also summoned from Glasgow.

The rioters were confident enough, on occasion, to

The rioters were confident enough, on occasion, to

launch showers of stones at combined groups of Constables, Infantry and Cavalry and some attempts were made to unhorse the Cavalry with wooden blocks placed across the streets. When the authorities issued a proclamation on Wednesday 15th September 1819 imposing a curfew

and offering a reward for information on the rioters, the worst of the violence was already over. Apart from injuries to many of the Special Constables, windows in many public buildings and private houses had been broken, along with

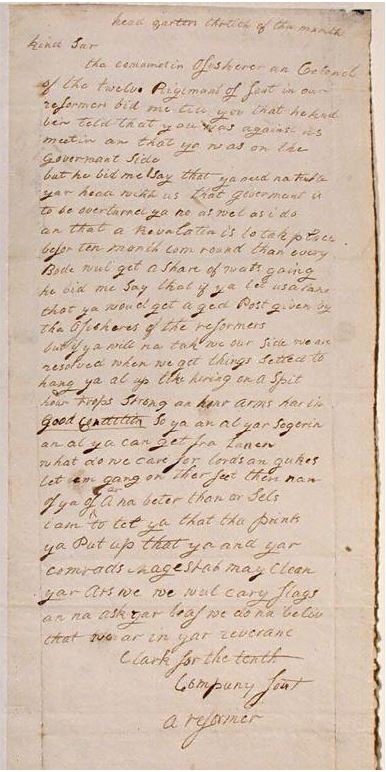

Anonymous Letter from a "Reformer", 1819

.

After a week of disturbances in September 1819, Paisley settled into an uneasy quiet. The town and county authorities expressed relief that the tumultuous proceedings had been suppressed without bloodshed, but agreed on the necessity

.

After a week of disturbances in September 1819, Paisley settled into an uneasy quiet. The town and county authorities expressed relief that the tumultuous proceedings had been suppressed without bloodshed, but agreed on the necessity

of establishing a permanent military garrison in the town as soon as arrangements allowed.

The Radical Reformers, however, remained defiant. A handwritten letter sent to the authorities by an anonymous Reformer spoke of military preparations among the Reformers and of the

The Radical Reformers, however, remained defiant. A handwritten letter sent to the authorities by an anonymous Reformer spoke of military preparations among the Reformers and of the

revolutionary overthrow of the Government which would take place within ten months. Those who opposed the Reformers would, when the time came, be hung up like herring on a spit.

Shortly after the letter was written, Reformers from Paisley and neighbouring villages marched

Shortly after the letter was written, Reformers from Paisley and neighbouring villages marched

to Johnstone for a meeting, flying flags with political slogans in defiance of the authorities as the anonymous Reformer had said that they would in his letter. Forewarned of the meeting, the authorities again had Cavalry at the ready throughout the day. On this occasion the

demonstrators dispersed peacefully, but there were soon disturbing rumours of Reformers preparing weapons and drilling after nightfall in readiness of a forthcoming insurrection.

- more to follow -

- more to follow -

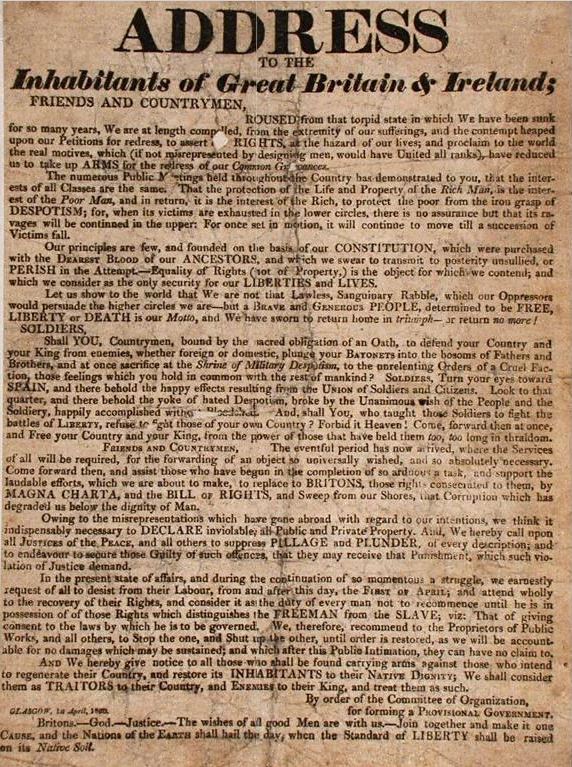

Address to the Inhabitants of Great Britain and Ireland, 1820.

.

On 1st April 1820, copies of the 'Address to the Inhabitants of Great Britain and Ireland' issued in the name of the 'Committee of organisations for forming a Provisional Government' were circulating throughout

.

On 1st April 1820, copies of the 'Address to the Inhabitants of Great Britain and Ireland' issued in the name of the 'Committee of organisations for forming a Provisional Government' were circulating throughout

much of the West of Scotland. The Address issued a call to arms, urged soldiers to join the battle for liberty, and invited those in work to strike immediately in support of the Provisional Government.

The effect of the revolutionary Address in Glasgow, Paisley and some of

The effect of the revolutionary Address in Glasgow, Paisley and some of

the other manufacturing towns and villages was immediate and remarkable. Almost the whole population of the working classes - around 60,000 people in total - obeyed the proclamation by striking work. An armed uprising was to follow, whenever news was received of the

outbreak of a popular revolt in England.

When it became clear that there was no popular uprising in England, plans for a widespread insurrection in Scotland were abandoned. Government spies had infiltrated the societies and organisations involved in preparing the

When it became clear that there was no popular uprising in England, plans for a widespread insurrection in Scotland were abandoned. Government spies had infiltrated the societies and organisations involved in preparing the

Rising and, unbeknown to virtually everyone active in it, the members of the 'Committee of Organisation' had been under arrest since 21st March. At the time and later, many felt that the events of the 1820 Rising had been instigated by Government spies and agent-provocateurs.

Assault on the Prison of Greenock, 1820

.

Attempts to organise armed support for the insurrection in April 1820 took place in the suburbs of Glasgow and in many of the manufacturing villages in the counties of Lanark, Renfrew, Ayr, Dumbarton and Stirling.

.

Attempts to organise armed support for the insurrection in April 1820 took place in the suburbs of Glasgow and in many of the manufacturing villages in the counties of Lanark, Renfrew, Ayr, Dumbarton and Stirling.

Following its failure, the authorities were soon at work arresting those suspected of involvement, who faced charges of High Treason with the grim punishment which that implied.

On Saturday 8th April, a detachment of Port Glasgow Volunteers provided an escort for five

On Saturday 8th April, a detachment of Port Glasgow Volunteers provided an escort for five

Radical prisoners who were being transferred from an overcrowded Paisley Tolbooth to Greenock Jail.

Despite attentions of a hostile Greenock crowd, they succeeded in delivering their prisoners to the Jail. On their return march, however, goaded and intimidated beyond

Despite attentions of a hostile Greenock crowd, they succeeded in delivering their prisoners to the Jail. On their return march, however, goaded and intimidated beyond

endurance, they ended up firing into the stone-throwing Greenock mob, killing eight and wounding ten others. In revenge, an angry mob stormed Greenock Jail, overpowered the military guard and released the Radical prisoners.

Despite the reward offered by the Greenock Magistrates, only one of the prisoners was recaptured.

- more to follow -

- more to follow -

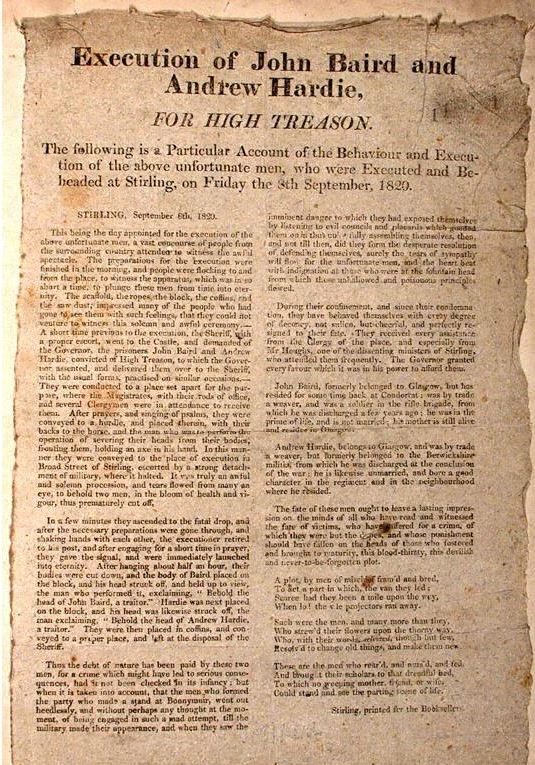

Execution of John Baird and Andrew Hardie for Treason, 1820

.

In the aftermath of the failed rising of 1820, the authorities exacted a grim and bloody retribution on its leaders.

Some leading reformers managed to make their escape from the country, but there was to be no

.

In the aftermath of the failed rising of 1820, the authorities exacted a grim and bloody retribution on its leaders.

Some leading reformers managed to make their escape from the country, but there was to be no

escape for nineteen radicals convicted of High Treason and transported, as an act of mercy, to New South Wales, nor for James Wilson, Andrew Hardie and John Baird.

Found guilty of Treason for leading a group of armed reformers from Strathaven towards Glasgow, James Wilson

Found guilty of Treason for leading a group of armed reformers from Strathaven towards Glasgow, James Wilson

ascended the scaffold at Glasgow Green on 30th August 1820, where he was hanged and beheaded as an angry crowd looked on. On 8th September, Andrew Hardie and John Baird followed Wilson to the scaffold, hanged and butchered outside Stirling Prison for their part in the

rising, including an armed stand against a troop of cavalry at the 'Battle of Bonnymuir.' Accounts of the executions circulated at the time reflected great popular sympathy for the victims who, it was felt, suffered for a crime for which others were responsible.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter