THREAD: Time for a welcome distraction.

Which passage of the Bible comes to mind when you think about a garden, a tree, thorns, angels, swords, and flames?

Genesis 2–3, right?

It’s an option. But so is John 18–19.

For more details, please scroll down.

Which passage of the Bible comes to mind when you think about a garden, a tree, thorns, angels, swords, and flames?

Genesis 2–3, right?

It’s an option. But so is John 18–19.

For more details, please scroll down.

Image: « http://deviantart.com »

John’s passion narrative is a work of genius.

At one level, it’s simply a historical narrative—an account of events which took place in 1st century AD Israel.

At one level, it’s simply a historical narrative—an account of events which took place in 1st century AD Israel.

It describes the death of a man named Jesus,

who died at the time of the Passover,

at the hands of a governor named Pilate.

who died at the time of the Passover,

at the hands of a governor named Pilate.

These details are historically verifiable (e.g., we have independent attestation of the time of Jesus’ death and the governorship of Pilate),

and are part of a credible historical sequence of events:

and are part of a credible historical sequence of events:

Jerusalem’s leaders want Jesus killed,

but, since they don’t want to—and can’t legally—do it themselves, they send Jesus to Pilate.

To their chagrin, Pilate declares Jesus to be innocent,...

but, since they don’t want to—and can’t legally—do it themselves, they send Jesus to Pilate.

To their chagrin, Pilate declares Jesus to be innocent,...

...which prompts the Jewish leaders to stir up the crowds (gathered in anticipation of the Passover) against him,

and, anxious to prevent civil unrest, Pilate kowtows to the Jews’ wishes.

and, anxious to prevent civil unrest, Pilate kowtows to the Jews’ wishes.

John’s passion can hence be read in a straightforward historical manner.

Submerged beneath its surface, however, are multiple undercurrents of intrigue and imagery,

each of which hints at the deeper significance of what takes place on Calvary’s cross.

Submerged beneath its surface, however, are multiple undercurrents of intrigue and imagery,

each of which hints at the deeper significance of what takes place on Calvary’s cross.

For a start, John’s narrative raises political questions.

If Jesus is a king, then what kind of king is he?

What and where is his kingdom?

And what exactly is the ‘power from above’ which is granted to Pilate?

If Jesus is a king, then what kind of king is he?

What and where is his kingdom?

And what exactly is the ‘power from above’ which is granted to Pilate?

At the same time, John’s passion is laden with sacrificial imagery.

We have a victim bound with cords (like a sacrifice),

led into a priestly courtyard with a fire (like an altar) at its centre.

We have a victim bound with cords (like a sacrifice),

led into a priestly courtyard with a fire (like an altar) at its centre.

And, later, we see Jesus surrounded by cultic imagery such as wood, scarlet fabric, hyssop (dipped in wine/blood), and fresh water (cp. Leviticus 14).

In addition, John’s passion has a legal dimension.

Jesus is declared innocent by Jerusalem’s legal authorities, yet is nevertheless treated as a guilty party,

which is an enactment of the theological significance of Jesus’ death;

Jesus is declared innocent by Jerusalem’s legal authorities, yet is nevertheless treated as a guilty party,

which is an enactment of the theological significance of Jesus’ death;

indeed, it is the very re-assignment of guilt described in Isaiah 53, where YHWH’s ‘righteous servant’ is ‘reckoned among the transgressors’—or, in Pauline terms, where God makes ‘him who knows no sin’ to be ‘sin on our behalf’.

In the present thread, however, I want to consider a different layer of imagery altogether, namely creation-related imagery.

——————

——————

That John’s passion narrative contains allusions to creation is well known.

John’s Gospel opens in darkness, against the backdrop of which the Spirit hovers above the waters (of baptism),

and a greater and lesser light emerge (Jesus and John).

John’s Gospel opens in darkness, against the backdrop of which the Spirit hovers above the waters (of baptism),

and a greater and lesser light emerge (Jesus and John).

And, in John’s passion, we again encounter creation-related imagery: a garden, a source of life drawn forth from a man’s side, and so on.

John’s use of these images is often skimmed over lightly, as if John’s intention was simply to bring to mind the general notion of creation (because a new era was about to dawn in his Gospel).

Yet John’s use of imagery is careful, specific, and precise.

Yet John’s use of imagery is careful, specific, and precise.

It can be divided up into three broad categories, each of which has its own individual purpose.

——————

——————

First, high-level imagery.

John’s narrative involves a number of images which are intended to define its overall context.

Unlike the Synoptics’, John’s passion is set within a garden.

John’s narrative involves a number of images which are intended to define its overall context.

Unlike the Synoptics’, John’s passion is set within a garden.

To be precise, it is bookended by two references to gardens—first the garden near the river Kidron, and second the garden in which Jesus’ tomb is located.

In addition, while the Synoptics emphasise a period of darkness which overshadowed Jerusalem at the time of the crucifixion, John’s entire passion is enshrouded in darkness.

It is initiated by Judas, as he heads out into the night (to betray his master).

It is initiated by Judas, as he heads out into the night (to betray his master).

It begins in earnest when Jesus is arrested in the ‘dark valley’ (‘Kidron’ = ‘darkness’).

And it concludes as Nicodemus, who has come to Jesus by night (a detail John repeats in his passion narrative), carries Jesus’ body away.

And it concludes as Nicodemus, who has come to Jesus by night (a detail John repeats in his passion narrative), carries Jesus’ body away.

Note: As Mary sets out for Jesus’ tomb on the first day of a new week, it is still dark.

These details are uniquely Johannine and are significant.

For John, Jesus’ crucifixion is decreational.

At the close of John’s passion week, darkness descends on a land in which great violence has been done, just as the floodwaters once enveloped the pre-flood world.

For John, Jesus’ crucifixion is decreational.

At the close of John’s passion week, darkness descends on a land in which great violence has been done, just as the floodwaters once enveloped the pre-flood world.

It is a bleak scene.

Yet John’s is not a darkness which will overcome the light; it is a darkness which marks the cusp of a new era, pregnant with hope and anticipation.

And, in ch. 20, that hope is realised.

Yet John’s is not a darkness which will overcome the light; it is a darkness which marks the cusp of a new era, pregnant with hope and anticipation.

And, in ch. 20, that hope is realised.

In and through Jesus’ resurrection (the Son-rise), the darkness is dispelled and new life sprouts forth from the ground.

God’s good creation will not end in death and de-creation.

——————

God’s good creation will not end in death and de-creation.

——————

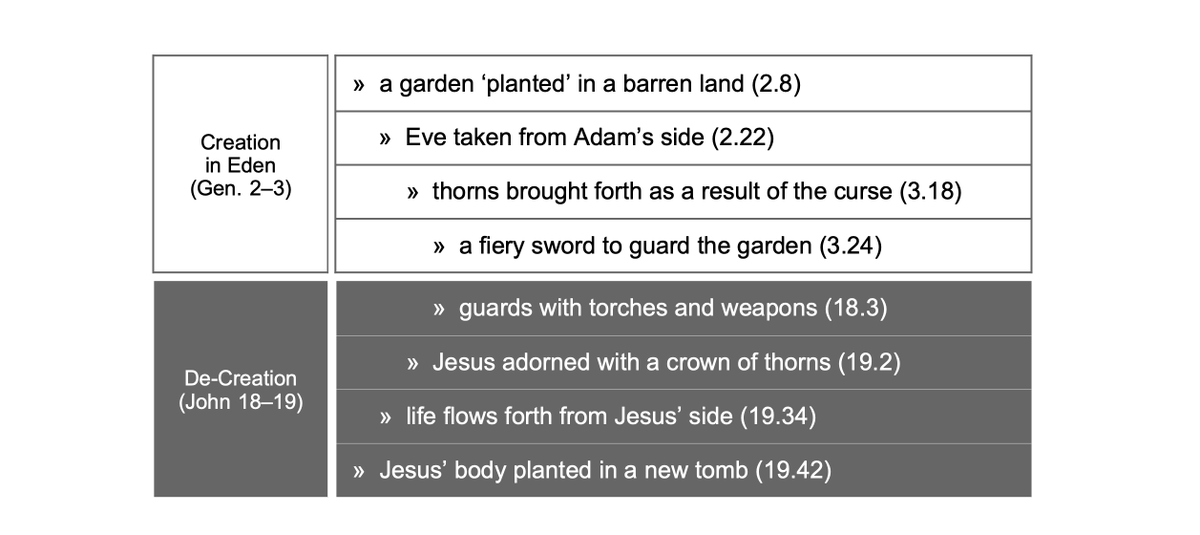

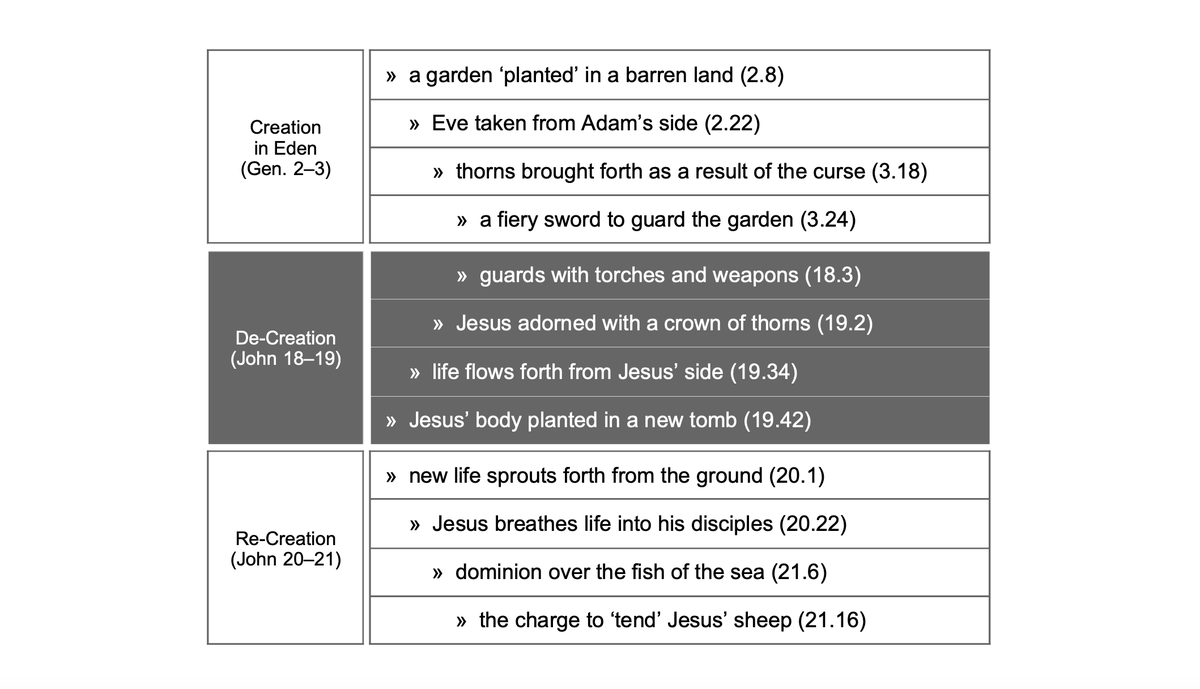

Second, ordered imagery.

John’s narrative involves a selection of images ordered in such a way as to depict a reversal of man’s fall.

John’s narrative involves a selection of images ordered in such a way as to depict a reversal of man’s fall.

These images begin with allusions to the effects of Adam’s sin (Genesis 3),

rewind through the cultivation of Eden (Genesis 2b),

and end in a barren garden (Genesis 2a), as shown below:

rewind through the cultivation of Eden (Genesis 2b),

and end in a barren garden (Genesis 2a), as shown below:

As can be seen, as we read through the events described in Genesis 2–3, we move from a barren garden to its (divine) cultivation to the commission and fall of mankind,

while, as we read through the events of John 18–19, we move through the same events arranged in reverse order.

while, as we read through the events of John 18–19, we move through the same events arranged in reverse order.

First, Jesus passes the garden’s guards (equipped with torches and weapons), who fall backwards as he announces his identity (‘I am the one!’). The way to the tree of life is about to be reopened.

Afterwards, Jesus approaches Pilate’s judgment seat, where he is crowned with thorns—i.e., where he takes responsibility for Adam’s sin—and tastes the dryness of the curse (‘I thirst!’).

Next, a spear is thrust into Jesus’ side as he pays the price for Adam’s sin (‘You shall surely die!’).

And, finally, just as Eden is ‘planted’ in a land in which no man has worked, so Jesus is planted in a tomb in which no man has laid. Like Adam, he ‘returns to the ground’.

And, finally, just as Eden is ‘planted’ in a land in which no man has worked, so Jesus is planted in a tomb in which no man has laid. Like Adam, he ‘returns to the ground’.

John’s narrative hence brings us back to a time prior to man’s transgression, a place prior to man’s expulsion, and a state prior to creation’s curse.

(And, aside from its reference to Jesus’ crown of thorns, it does so with uniquely Johannine imagery.)

(And, aside from its reference to Jesus’ crown of thorns, it does so with uniquely Johannine imagery.)

Yet the barrenness of John 19’s garden is not the barrenness of a land which has become dry or infertile;

it is a barrenness which anticipates new life, since buried within it is the body of Jesus.

it is a barrenness which anticipates new life, since buried within it is the body of Jesus.

A grain of wheat has died and fallen into the ground, and will soon bear much fruit.

Hence, in John’s new creation, on the back of Jesus’ resurrection, the disciples receive a new Adamic commission.

Hence, in John’s new creation, on the back of Jesus’ resurrection, the disciples receive a new Adamic commission.

The disciples’ new ‘life’ isn’t merely physical breath, but the Spirit of life, and is inherently connected to the forgiveness of sins (20.23).

Meanwhile, the disciples’ dominion over the fish of the sea concerns their role as ‘fishers of men’, and their charge to tend Jesus’ sheep is a continuation of the work of Jesus, the Good Shepherd.

——————

——————

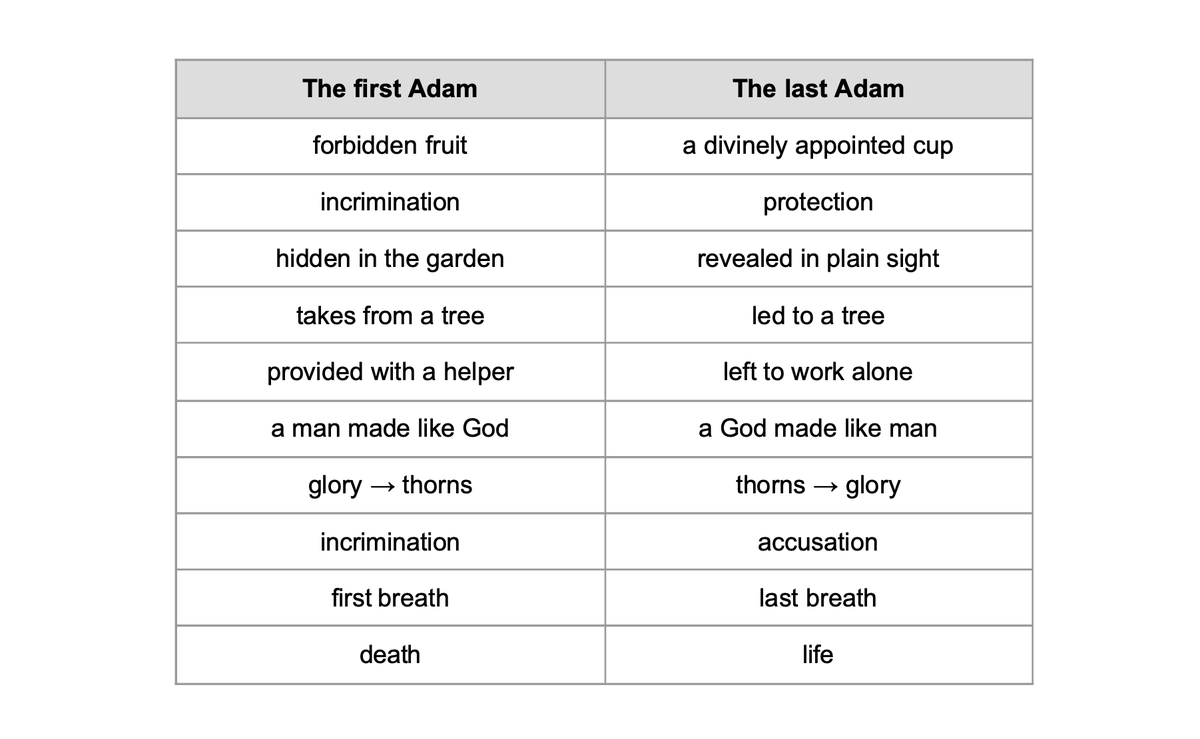

Third, inverted imagery.

John’s narrative involves a number of images which stand in contrast to those of Genesis 2–3 and, by extension, portray Jesus as the man who triumphs where Adam fails.

John’s narrative involves a number of images which stand in contrast to those of Genesis 2–3 and, by extension, portray Jesus as the man who triumphs where Adam fails.

Whereas the first Adam consents to eat forbidden fruit, the last Adam consents to drink from a divinely appointed cup.

Whereas the first Adam incriminates (‘The woman gave it to me!’), the last Adam protects (‘Let these men go!’).

Whereas the first Adam incriminates (‘The woman gave it to me!’), the last Adam protects (‘Let these men go!’).

Whereas the first Adam hides in the garden, the last Adam steps forward, and, whereas the first Adam fails to take responsibility for his sin, the last Adam takes responsibility for the sins of others.

Whereas the first Adam takes fruit from a tree in disobedience, the last Adam is led to a tree in obedience.

Whereas the first Adam is provided with a helper, no-one is able to help the last Adam in his work. Like the Levitical high priest, he must enter the sanctuary alone.

Whereas the first Adam is provided with a helper, no-one is able to help the last Adam in his work. Like the Levitical high priest, he must enter the sanctuary alone.

Whereas God declares ‘Behold the man!’ at the end of the first Adam’s trial, since man in his pride has ‘become like God’, Pilate declares ‘Behold the man!’ at the end of the last Adam’s, since God in humility has become like man.

Whereas the first Adam is given glory and honour, later to be exchanged for a crown of thorns, the last Adam is given a crown of thorns, later to be exchanged for a crown of glory.

Whereas the first Adam’s reference to a ‘woman’ is an accusation, the last Adam’s (‘Woman, behold your son!’) provides for his mother.

Whereas the first Adam takes his first breath in the garden, the last Adam takes his last.

Whereas the first Adam takes his first breath in the garden, the last Adam takes his last.

And, whereas the first Adam’s failure brings death on his descendants, the last Adam’s triumph brings life to his people. Per Caiaphas’s suggestion, ‘one man dies for the nation’.

In short, where Adam fails, Jesus triumphs.

——————

In short, where Adam fails, Jesus triumphs.

——————

REFLECTIONS:

John’s narrative brings all of the aforementioned images together into a single and beautiful story,

which is not a story of his invention, but a record of historical events.

And creation-related imagery is merely one of its many strands.

John’s narrative brings all of the aforementioned images together into a single and beautiful story,

which is not a story of his invention, but a record of historical events.

And creation-related imagery is merely one of its many strands.

Jesus is not only the last Adam, who heads back into the garden and unravels the effects of the fall;

he is also the prophet who speaks truth to Pilate’s power,

the sacrifice on God’s holy altar,

the priest who offers himself up before God,

and the king of a royal kingdom.

he is also the prophet who speaks truth to Pilate’s power,

the sacrifice on God’s holy altar,

the priest who offers himself up before God,

and the king of a royal kingdom.

‘Never has a man spoken like this man’,

nor has any man acted like him.

And one day he will return to our fallen world to take his rightful place.

‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom!’.

THE END.

With thanks to Nicholas Schaser’s 2020 paper, ‘Inverting Eden’.

nor has any man acted like him.

And one day he will return to our fallen world to take his rightful place.

‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom!’.

THE END.

With thanks to Nicholas Schaser’s 2020 paper, ‘Inverting Eden’.

P.S. Please retweet if you’ve enjoyed these thoughts and would like to distract others with them.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter