(Thread) I have a story for you. A story about medieval employment law, in a time of pandemic. A story set in the year 1410, when an ambitious lad who spent years shovelling horse manure finally secured a coveted training contract to enter the legal profession, only to be sued

(2) by his former employer. It starts with a "writ on the statute of Labourers" in the Court of Common Pleas, held at Westminster Hall. If you'd like to know more abt medieval courts and procedure, read the linked article, otherwise read on for the story; https://orderofthecoif.wordpress.com/2018/03/04/a-day-in-the-life-of-a-15th-century-barrister/

(3) The Statute of Labourers 1351, the first employment law statute, was a product of the Black Death. In 1348, the Bubonic Plague arrived in medieval Italy, and even in a time of painfully slow communications, within a year it had reached even the remotest English villlage.

(4) It was deadly beyond all previous known diseases, killing around a third of the population. Many interpreted it as a sign of God's wrath for sin. The king of France's astrologer asserted it was the result of an unfortunate conjunction of three planets in 1345.

(5) Whatever the cause, it killed off huge numbers of people, in every social strata but particularly the poor. An unexpected effect, however, of removing a third of working-age individuals from the labour market was to create a profound labour shortage. As a result, wages

(6) skyrocketed even as prices fell. Some peasants simply dropped their ploughs and walked off the land. Many others took the opportunity to renegotiate their relationship with their lord and become leasehold farmers paying a cash rent. It was the death of serfdom in England.

(7) The upper classes were horrified by the impudence of working-class people demanding higher wages, and in 1349 the king passed the Ordinance of Labourers. As his lawyers would have told him, he lacked the power to alter the common law by executive fiat, and in the parliament

(8) of 1351 the tenor of the ordinance was enacted as statute law. It says it is directed against the "malice of servants who are idle and unwilling to serve after the pestilence without excessive wages". It provided for three major emplaw provisions; first, it fixed wages at

(9) pre-plague levels (extremely low given England was overpopulated). Second, those lacking a landed income sufficient to support themselves, if unemployed, could not refuse an offer of employment. If they did, they could be imprisoned. Third, they could not hire out their

(10) labour by the day but only by the year. They could not leave their master's employ within that year without licence or exceptional circumstances. While the statute speaks of criminal enforcement, the common law courts innovated civil procedures both against "idle servants"

(11) and also against masters who took into their service servants who had left their previous master unlawfully. And this is the crux of the issue; the upper classes themselves ignored the statute, paid higher wages and pinched employees from other masters. This led to

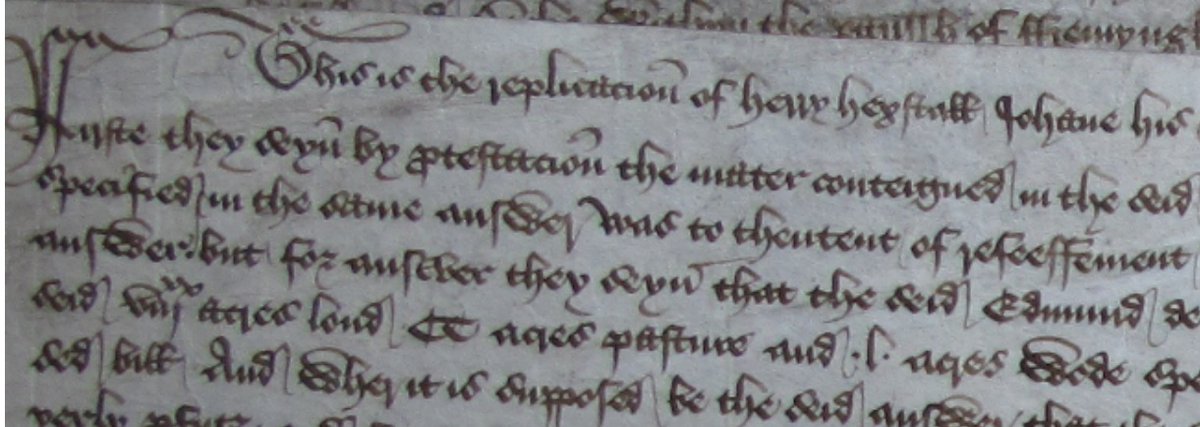

(12) litigation, and the present case. The writer of the the medieval law reports, known as 'Year Books' (20,000 such cases fully translated, cross-referenced and searchable thanks to the magnificent Professor Seipp of Boston University), did not record or particularly care about

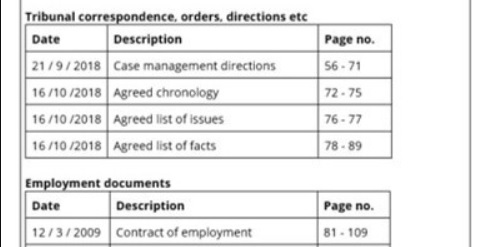

(13) the names of the parties, or even the ultimate outcome. They recorded legal argument at hearings occurring at Westminster Hall, which were mostly preliminary hearings to secure 'joinder of issue' (or agree a 'list of issues' for you emplaw practitioners), before remitting

(14) it to a jury (as civil juries were still a thing back then) to decide and render verdict on issues of fact. So we have a "writ on the Statute of Labourers" brought in the Court of Common Pleas in 1410. The plaintiff alleges that he hired the defendant servant in an "animal

(15) husbandry" position, on a yearly basis, for four years, but in the fifth year the lad left without licence, in contravention of the statute and his covenant of employment. The plaintiff also brings an action against the defendant master for taking in the lad and giving him

(16) a seven-year apprenticeship as a scrivener. Scriveners were the profession that drew up legal documents, and were an integral part of the legal profession. There is no doubt that this was an extraordinary opportunity for the lad, to go from manual labour to a literate

(17) professional career / apprenticeship. It was an opportunity and social mobility leap that perhaps one in one hundred boys of his class might make (often through the church, but as has always been the case, the legal profession is a machine for upward social mobility). The

(18) defendants were repped by the talented Serjeant (medieval QC) Chaunterell, who enjoyed an exceptionally long and successful career at the peak of the bar. 26 years after this case he is recorded doing an arbitration on a dispute between a baron and three sisters over a manor

(19) Serjeant Chaunterell tried several legal arguments (demurrers) to avoid going to a jury trial. He argued first that it was an improper form to bring a single writ against two defendants. The court shot down this argument (although, interestingly, accepted it in a later case

(20) where two serjeants acted as legal aid advocates for two vagrants who an abbot demanded enter his service, and sued them for failing to comply). Chaunterell then said that the defendant master had engaged the lad as an apprentice, not as a servant, and thus this was outside

(21) the scope of the statute. The court also shot down this argument. The Year Book then records (translated), "All the Court said that defendants should deny that defendant servant was defendant master's servant". What this means is that the entire bench of six justices said

(22) the only defence was to plead a factual denial (a "traverse") that he had taken the lad into his service. Pleading a traverse would lead to joinder of issue (the issue for the jury would be, "Did D take servant into his service?") and remitting of the issue to a jury. It was

(23) clearly not an issue on which they could win. Then, as now, winning the arguments at the preliminary hearing about what issues most favourable to your client would go forward to liability stage, was extremely important. Babington CJCP (Chief Justice Common Pleas) then

(24) issued a ruling that apprentices are servants for the purposes of the statute of Labourers. That is where the Year Book writers leave the story. They had little interest in what happened to the characters, only the legal argument at the preliminary hearing. I'd like to hope

(25) that the defendants successfully applied for a 'licence to imparl' (an adjournment to engage in settlement negotiations), and that they were able to resolve this, and the lad went on to a successful career as a scrivener. We don't know, but I'll fill the gaps with my wishful

(26) thinking and imagination. If you've enjoyed this thread, please consider making a donation to the Citizens Advice Bureau. At the moment they are working night and day to provide free employment law advice to those caught in the covid disaster. Please give generously if u can

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter