(Thread on Money & Credit: 1/n) How does monetary policy affect #Pakistan's economy? Which economic agents adjust their behaviour the most in response? Wat led to the recent crisis and why the broad money supply has increased so much since Nov-19? Let's look at all this below.

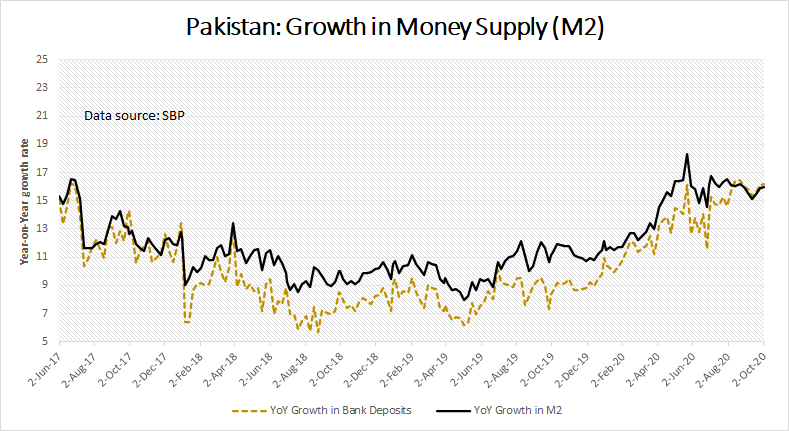

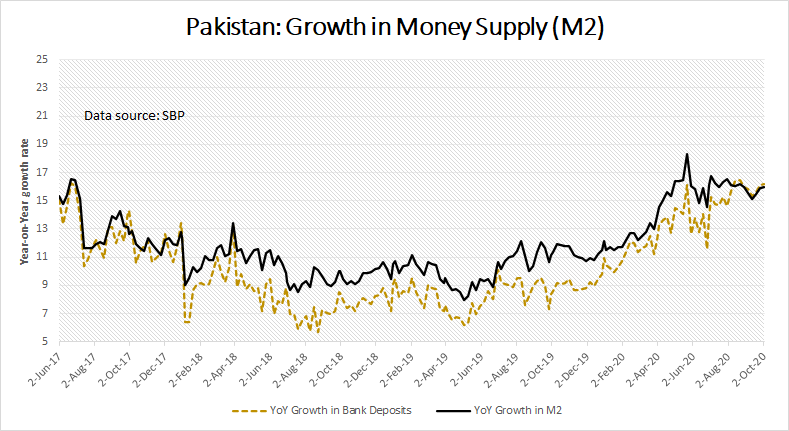

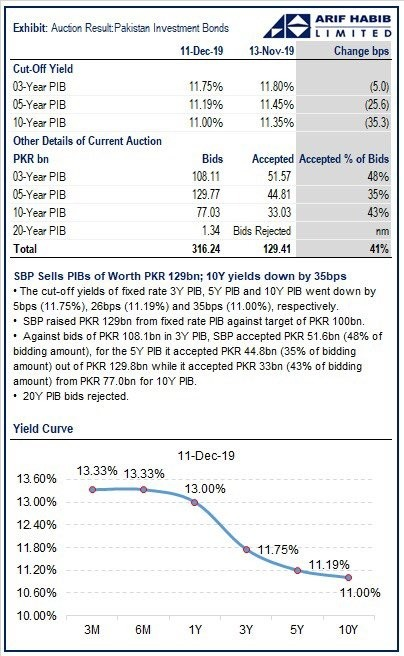

(2/n) The figure in (1/n) shows that, after remaining stable between 2018-20, growth in broad money supply has increased considerably from 11% in Nov-19 to 16% now. This trend took off much before COVID & can have implications going forward. We return to this later in (8/n).

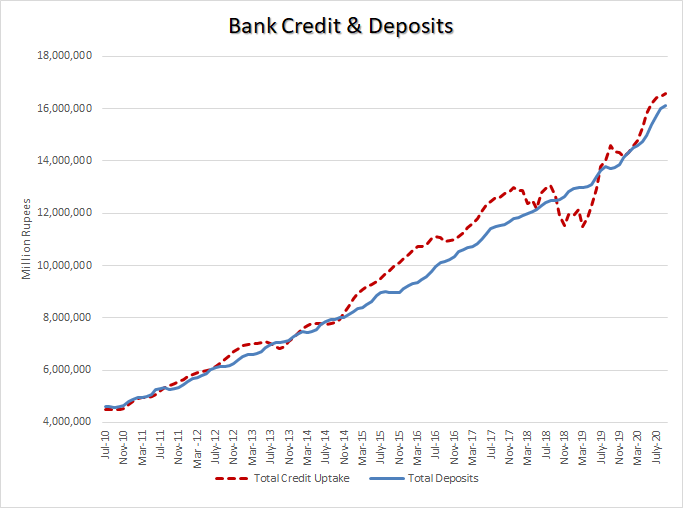

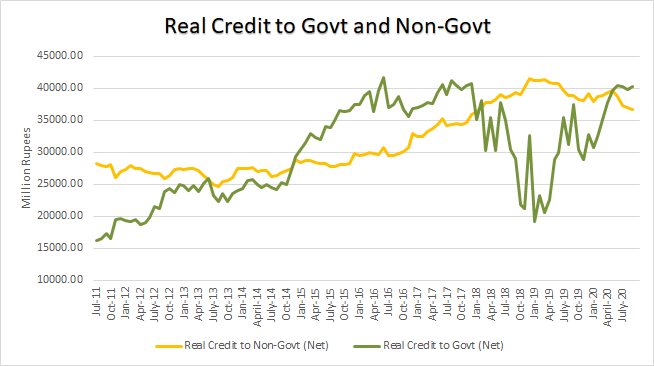

(3/n) First, some history. This graph shows that total credit (private & govt) & bank deposits move together. But something changed in 2015. Total credit started growing much faster between 2015-17. It then collapsed between 2017-19 before recovering back to its trend.

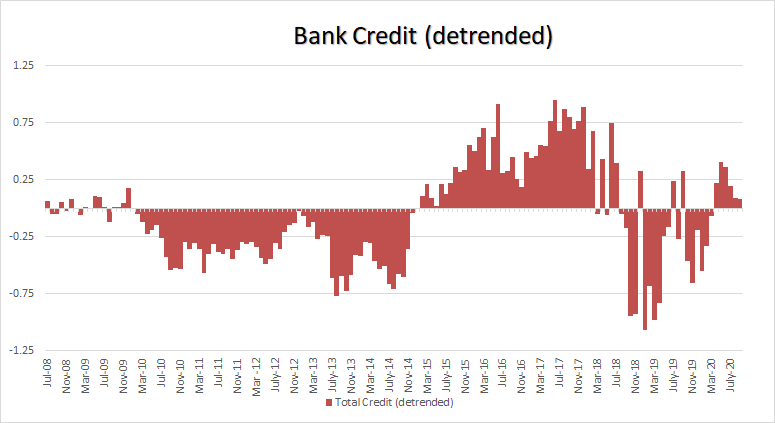

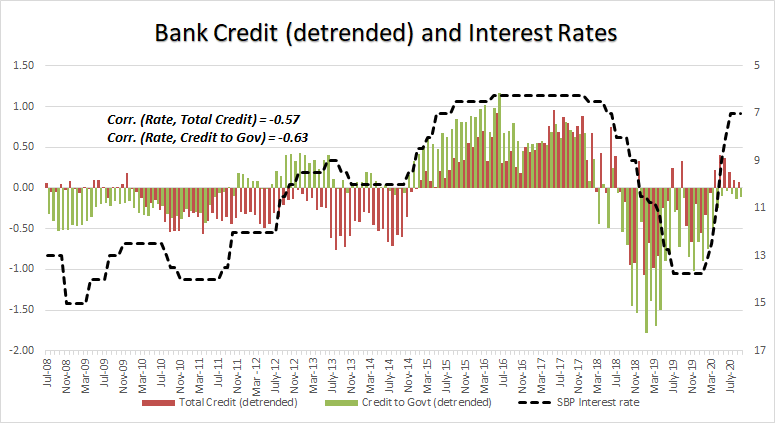

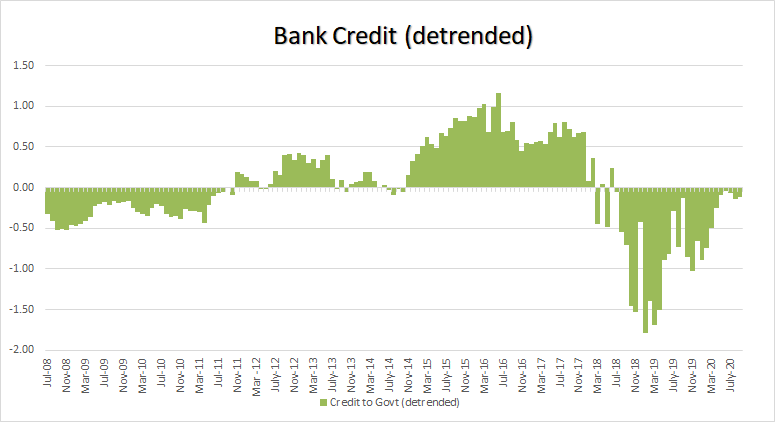

(4/n) Adjusting data on credit uptake (from Jul-07 until Sep-20) for inflation and then detrending the series shows an even clearer picture. Total credit uptake (in real terms) started to increase above its trend from Jan-15 and continued to stay so all the way till elections.

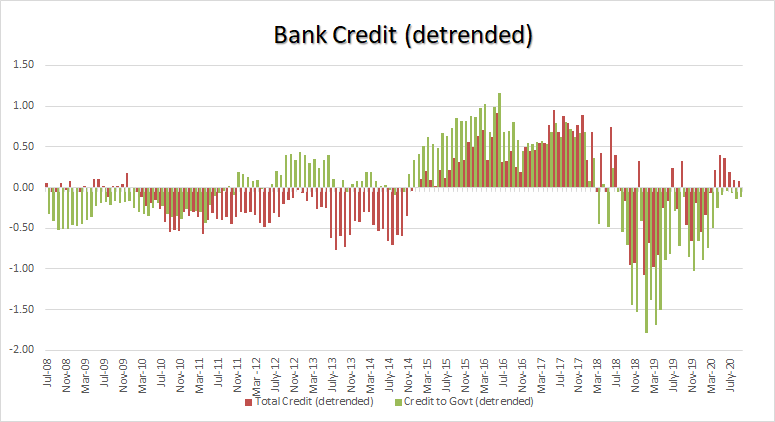

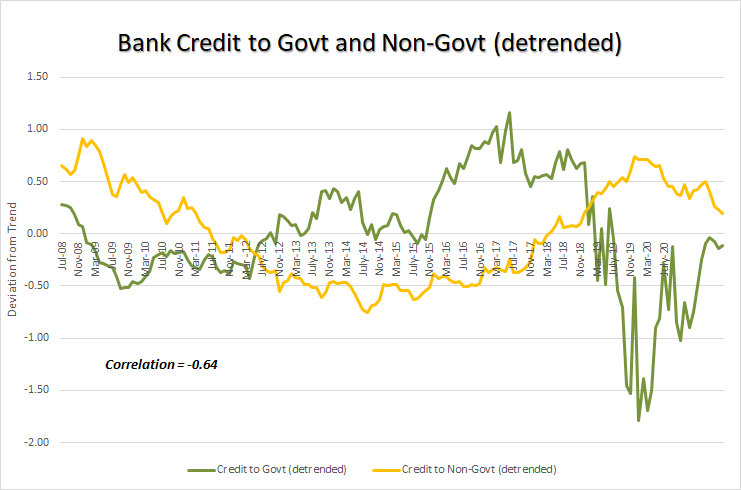

(5/n) It turns out that much of the boom and then the collapse in credit uptake was driven by an increase in government borrowing. While credit to non-govt sector did increase as well from 2016 onwards, it does not explain much of the boom-bust we see in total credit uptake.

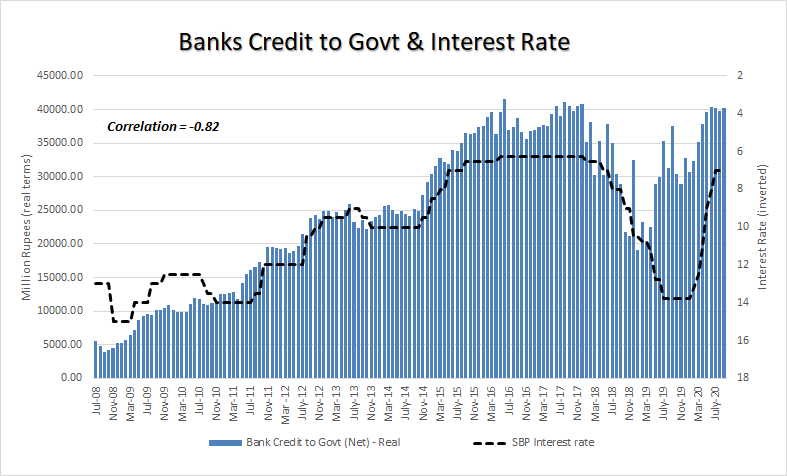

(6/n) Now the elephant in the room: why credit-to-govt behaved the way it did? Interest rates! The figure shows a strong correlation of -0.82 between (net) real credit uptake by govt and interest rates. The correlation is strong at -0.63 even after removing the trend component.

(7/n) What is the implication of this? Since (net) government borrowing equals 55% of bank deposits and close to 40% of broad money supply on average, changes in interest rate have a significant effect on aggregate demand via changes in (net) real credit uptake by government.

(8/n) While different datasets continue to point in the same direction that the economy was starting to overheat from 2016 onwards, the policymakers (both fiscal and monetary) did not respond and delayed important decisions until the crisis was inevitable. https://twitter.com/ajpirzada/status/1272512472654721024?s=20

(9/n) Now, what about the increase in money supply I mentioned in (2/n)? The increase in broad money supply since Nov-19 is largely driven by increase in the deposit component of money supply. This is quite obvious from the figure. But why are deposits increasing?

(10/n) With credit to non-govt sector not increasing much over this period, all of the increase in money supply (bank deposits) is explained by govt increasing its (net) borrowing frm banks (Note: see here on how new borrowing/loans increase money supply: https://bit.ly/384xOqp )

(11/n) In short, as borrowing costs started coming down from Oct-19 onwards, government once again increased its net borrowing from the banking system by a significant amount. While govt borrowing is still slightly below its trend, there is not much room for any misadventure.

(12/n) Besides, there is also a strong negative correlation of -0.64 between deviation in credit to govt and to non-govt sector. While this is not conclusive, it does point to government borrowing crowding out the private sector.

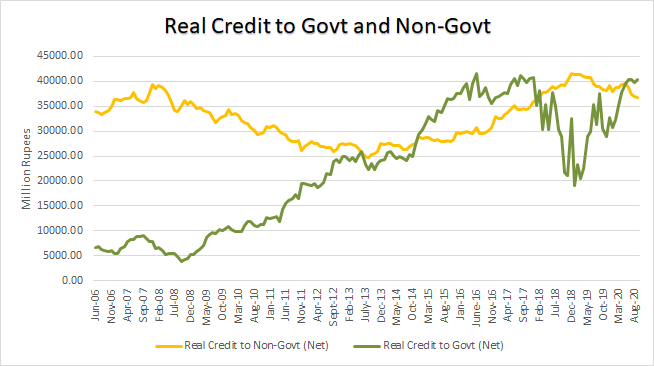

(13/n) Looking at the actual series all the way back to 2007 presents an even dramatic picture. Some structural change seems to have happened in 2008 which caused (net) govt borrowing to start increasing in real terms at the expense of private sector.

(14/n) As a result, the share of govt borrowing in broad money supply has increased from around 8% in 2007 to close to 40% now. This suggests that an important channel through which monetary policy affects aggregate demand today is via public/govt demand than via private demand.

(15/n) So, wat r the key takeaways? First, government borrowing is now an important part of broad money supply and, therefore, an important channel through which monetary policy affects aggregate demand. This is inline with what is suggested in this paper http://www.princeton.edu/~moll/HANK.pdf

(16/n) Second, since govt borrowing now plays such an important role in driving aggregate demand, fiscal authorities hav an even bigger incentive to undermine SBP & stop it from taking corrective measures when needed. Meaning, SBP autonomy is even more important now than before.

(17/n) Third, government should also keep an eye on its own actions to not cause any overheating down the road which may then create frictions between the fiscal and monetary authorities. Finally, government will have to step back and reduce its borrowing from the ...

(18/n) ... banking system if it wishes for the private sector to take the centre stage in how economic activity is organised. To expect private sector to step-up while absorbing any liquidity from the banking system yourself whenever borrowing conditions ease is counterintuitive.

(n/n) Growth is important. But policymakers must achieve it through productivity reforms than relying on policies which result in boom-bust cycles. This does make their life harder but that is wat they promise us before every election. We dont expect more! https://twitter.com/ajpirzada/status/1272312447370747911?s=20

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter