Halloween is viewed as a traditionally American cultural export enjoyed all over the world, but the spooky celebration actually has its roots in Ireland. It all dates back to ancient times when people across Ireland celebrated Samhain.

A traditionally Gaelic festival signalling the end of the harvest season and the beginning of the colder, darker nights that accompanied winter, Samhain was an annual night of celebrations that ran from October 31st to November 1st.

Bonfires were lit and rituals performed as part of a night many believed saw the real world and the world of the spiritual briefly intertwined.

Malevolent spirits were said to roam free, leading many to perform any number of strange ceremonies and incantations as a way of warding off these evil spectres.

It was believed by the Celts that on the night of 31st October, ghosts of their dead would revisit the mortal world and large bonfires were lit in each village in order to ward off any evil spirits that may also be at large.

Celtic priests, known as Druids, would have led the Samhain celebrations. It would also have been the Druids who ensured that the hearth fire of each house was re-lit from the glowing embers of the sacred bonfire

in order to help protect the people and keep them warm through the forthcoming long, dark winter months.

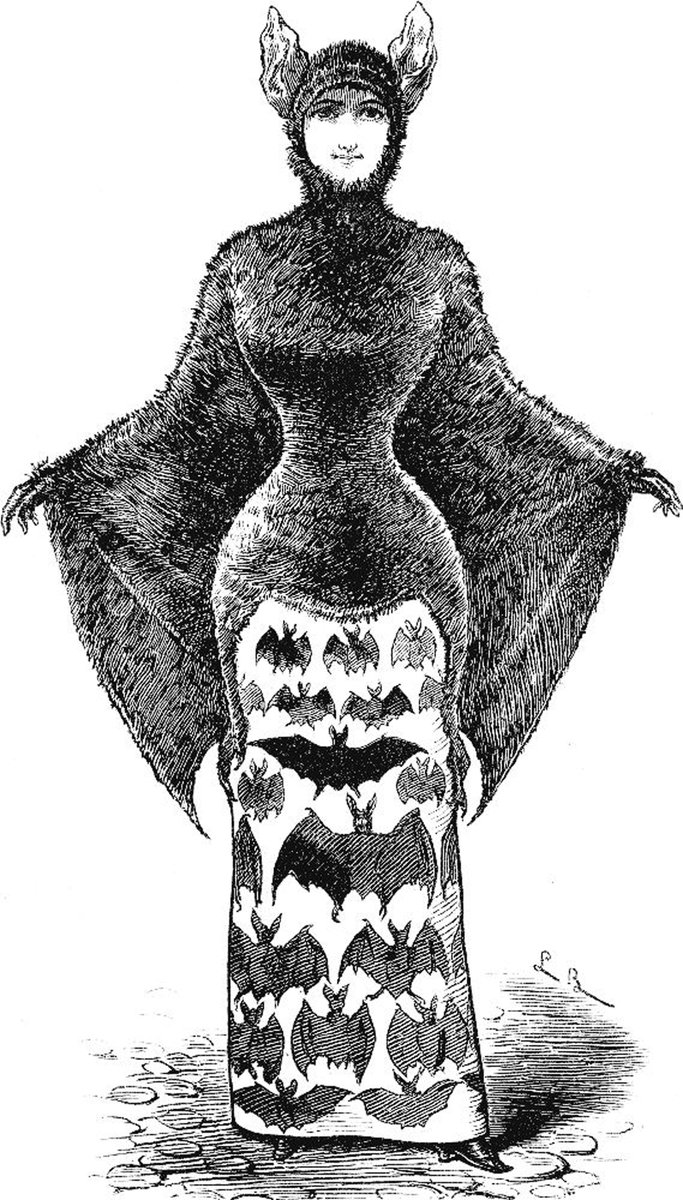

During the celebration, the Celts wore costumes, typically consisting of animal heads and skins, and attempted to tell each other’s fortunes.

In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III designated November 1 as a time to honor all saints. Soon, All Saints Day incorporated some of the traditions of Samhain. The evening before was known as All Hallows Eve, and later Halloween.

Hence, the Druidic festival that took place on October 31 st morphed into All Soul’s Evening (a.k.a. all Hallow’s Eve). The festival on November 1st became the Feast of All Saints. All Souls Day, the day to honor all dead, followed on November 2nd.

All Souls’ Day was celebrated similarly to Samhain, with big bonfires, parades and dressing up in costumes as saints, angels and devils.

By the 19th century, Samhain celebrations had completely become Christianised by the Church and renamed Halloween, amid concerns over Samhain's previous Pagan roots.

They were commonplace across Ireland, with the traditions of pranks and door-to-door donations evolving into something approaching trick-or-treats.

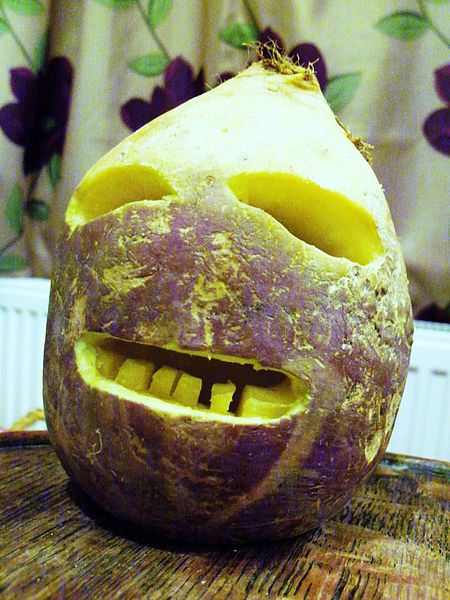

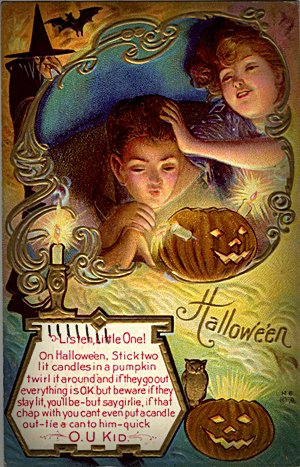

By this time Jack-O-Lanterns had also emerged as a popular tradition, though they were often carved out of turnips rather than pumpkins.

It is believed that the custom of making jack-o'-lanterns at Hallowe'en time began in Ireland. In the 19th century, "turnips or mangel wurzels, hollowed out to act as lanterns and often carved with grotesque faces," were used on Halloween in parts of Ireland.

By those who made them, the lanterns were said to represent either spirits or supernatural beings, or were used to ward off evil spirits. For example, sometimes they were used by Halloween participants to frighten people

and sometimes they were set on windowsills to keep harmful spirits out of one's home. It has also been suggested that the jack-o'-lanterns originally represented Christian souls in purgatory, as Halloween is the eve of All Saints' Day/All Souls' Day.

On Halloween in 1835, the Dublin Penny Journal published a long story on the legend of "Jack-o'-the-Lantern". In 1837, the Limerick Chronicle refers to a local pub holding a carved gourd competition and presenting a prize to "the best crown of Jack McLantern".

An old Irish folk tale from the mid-18th century tells of Stingy Jack, a lazy yet shrewd blacksmith who uses a cross to trap Satan.

One story says that Jack tricked Satan into climbing an apple tree, and once he was up there, Jack quickly placed crosses around the trunk or carved a cross into the bark, so that Satan couldn't get down.

Another version of the story says that Jack was getting chased by some villagers from whom he had stolen.He then met Satan,who claimed it was time for him to die.However, the thief stalled his death by tempting Satan with a chance to bedevil the church-going villagers chasing him

¡Jack told Satan to turn into a coin with which he would pay for the stolen goods (Satan could take on any shape he wanted); later, when the coin (Satan) disappeared, the Christian villagers would fight over who had stolen it.

The Devil agreed to this plan. He turned himself into a silver coin and jumped into Jack's wallet, only to find himself next to a cross Jack had also picked up in the village. Jack had closed the wallet tight, and the cross stripped the Devil of his powers; and so he was trapped.

In both folktales, Jack lets Satan go only after he agrees to never take his soul. Many years later, the thief died, as all living things do.

Of course, Jack's life had been too sinful for him to go to heaven; however, Satan had promised not to take his soul, and so he was barred from hell as well.

Jack now had nowhere to go. He asked how he would see where to go, as he had no light, and Satan mockingly tossed him a burning coal, to light his way. Jack carved out one of his turnips (which were his favorite food),

put the coal inside it, and began endlessly wandering the Earth for a resting place. He became known as "Jack of the Lantern", or jack o'lantern.

Nearly everyone in Great Britain also celebrated the holiday. Farmers and tenants came from far and wide to join in the festivities at Balmoral, but of all those celebrating perhaps, Queen Victoria was the most enthusiastic.

She noted in her diary on 31 October 1867 that she had taken a drive with someone and had to hurry back in order to be in time for the celebration.

Anglican colonists living in the south and Catholic colonists in Maryland all recognized All Hallow’s Eve while Puritans remained opposed to the holiday. Almanacs of the late 18th and early 19th century do not indicate that Halloween was widely observed in the United States.

That all changed in the 1840s when the advent of Ireland's devastating potato famine brought millions of Halloween-loving Irish immigrants over from across the Atlantic.

The Great Famine, also known as the Irish Potato Famine, was caused by a disease called the "potato blight" that affected Ireland's staple crop.

As a consequence, a million people died and a further million left the Emerald Isles. When the Irish diaspora arrived in America, their traditions came with them, including the Catholic festival of All Saints and All Souls

Halloween made its debut into proper American society circa the 1870s. Although by then Halloween superstitions and conjuring existed among many ethnic groups, the holiday was most often viewed as the quaint practice of the Scottish, English and Irish.

One of the first mentions of Halloween appears in Godey' s Lady's Book in October of 1872:

"HALLOWE'EN--Time in its ever-onward course, has once more brought us to the month in which this festival occurs. About the day itself there is nothing in any wise peculiar or worthy of notice,

but since time almost immemorial All Hallow Eve, or Hallow-een, has formed the subject theme of fireside chat and published story."

If the destructive element of Halloween was distasteful to Victorians, its Irish history was probably eqyally so. Strong anti-Catholic editorials were published in Harper's Weekly as late as 1875.

The upper classes preferred to remember that their ancestors in Northern England or Scotland, rather than thousands of Irish Catholic immigrants, brought Halloween to America, and that All Saints' Day was an Episcopalian religious day rather than a Catholic one.

Over the next 30 years Episcopal All Saints' Day celebrations grew more public and more popular. Although the Catholic church celebrated All Saints' Day in accordance with its years of history and heritage, it simply did not receive as much acknowledgment in the press.

As a result, vast numbers of American readers came to understand All Saints' Day as Episcopalian in origin.

In the South, Episcopalian All Saints' Day celebrations were reported to the general public, calling to mind descriptions of Halloweens in the churchyards of small Welsh or Irish villages. An Atlanta newspaper noted in 1895:

"The Episcopalians in the city will observe All Saints' Day this year with special devotional services, which will be conducted at 10 in the moming. . .when prayers will be offered for the souls of the faithful and departed. "

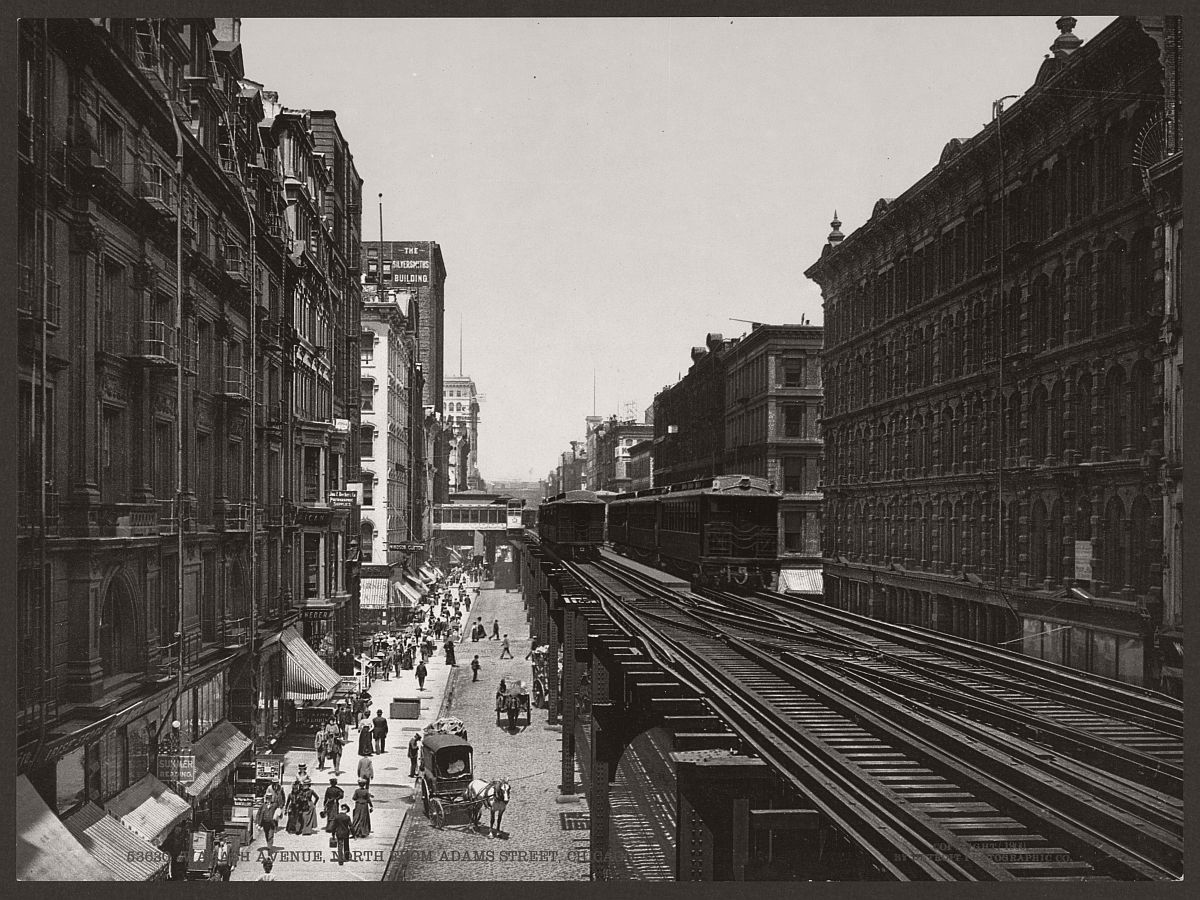

The Victorian middle classes emulated the upper classes, and the periodicals they both were offered often reflected the feelings of old New England stock. On the other hand, history was remembered differently in cities such as Boston or Chicago, where many Irish made their homes.

In the Boston Daily Globe of October 31, 1884, Halloween was given a rare good notice by an Irish joumalist in an article entitled "Why Thousands Will Think of Erin Tonight.":

"To be sure it is a fast night, as is customary on the eve preceding great holidays of the church, but in the evening it is one which, like our own New England Fast day,

knocks all religious or pious canons into smithereens as the lads and lasses enter into the fast and furious fun of its time-honored observance.

This is the season there when the well-to-do country cousins send to their relatives in the towns presents of the richest products of the farm, much of them intended for the components of the savory and hearty Colcannon feast."

Occasionally parties of young men and their sweethearts made the rounds of the houses of their relatives and friends on Halloween, participating in the fun and all joining at the residence of some one

favored with a dwelling of more suitable size for the accommodation of those participating in the fun and Fast day feasting.

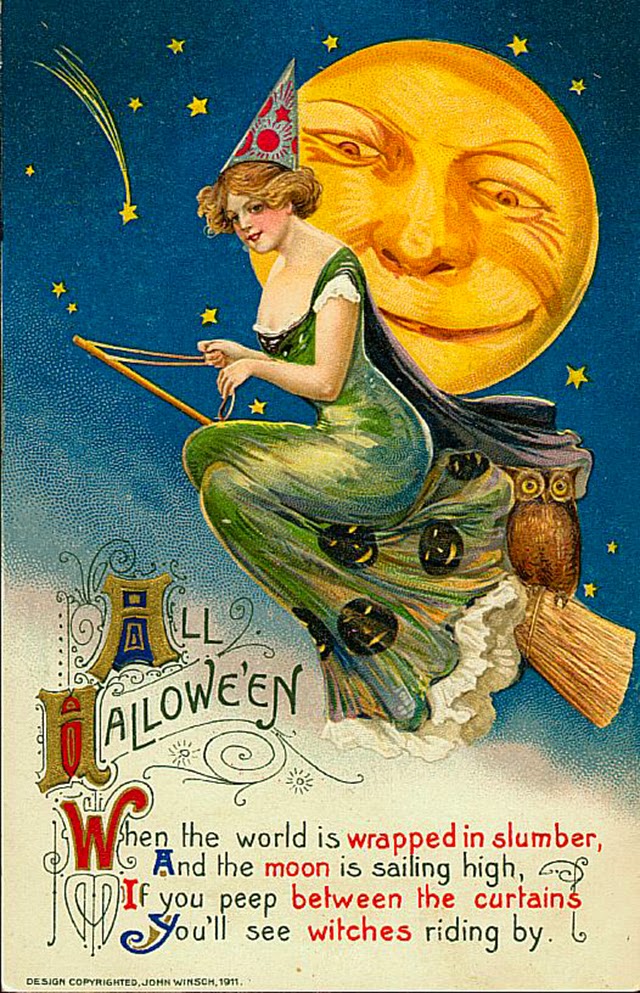

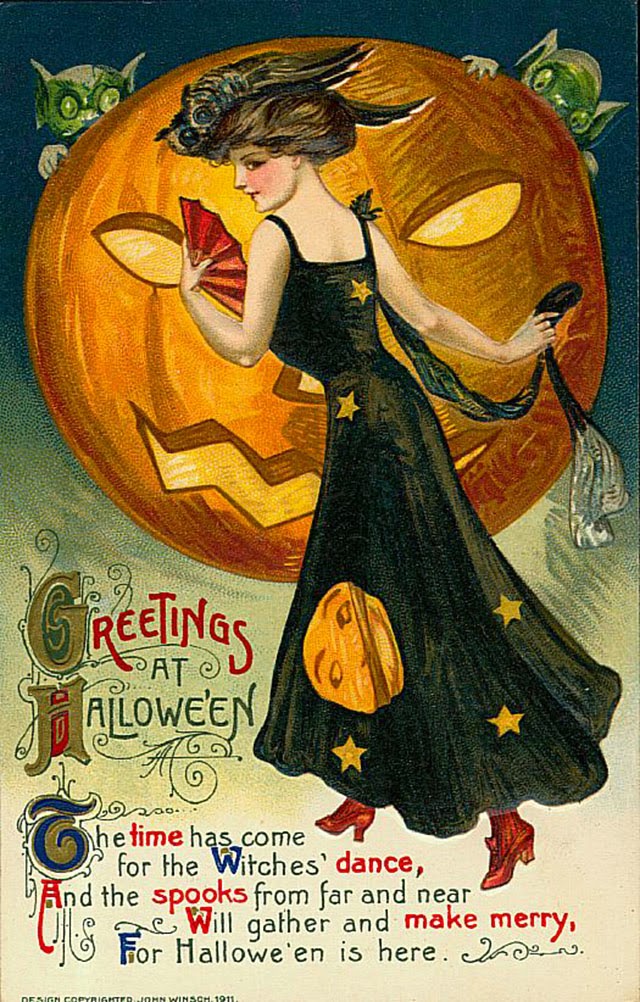

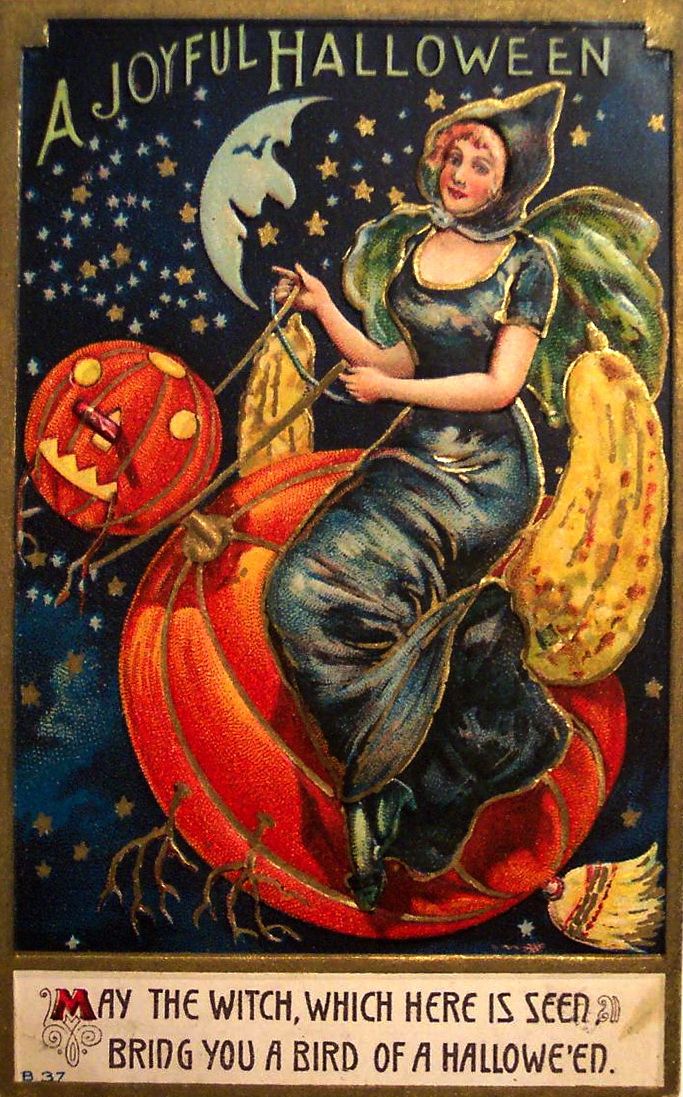

Children's magazines printed pretty pictures of fairies and witches; ladies' periodicals became concerned with how a Halloween party was given--decorating ideas, what foods to serve, how to break the ice.

In 1881, St. Nicholas Magazine intoned a death knell for the old-world "authentic" holiday: "..belief in magic is passing away, and the customs of AII-hallow Eve have arrived at the last stage;for they have become mere sports,repeated from year to year like holiday celebrations."

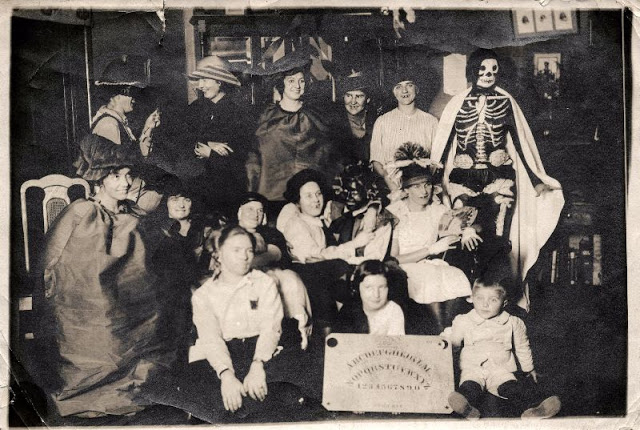

Halloween celebrations in the Victorian age seem to be made of one part romantic inspiration, one part reconstructed history, and one part Victorian marketing.

Halloween stories became almost operatic with regard to passion, and less concemed with actual ghosts. In and amongst the stories offered to female readers, which had such titles as "Love's Seed-time and Harvest," "Love Lies A-Bleeding" and "If I Were a Man I'd Shoot Myself,"

lie gems like "The Hallow-e'en Sensation at Gov'ner Dering's." In this tale the heroine is determined to live loveless because she believes the man she loves does not care for her. She takes up a dare to go into a dark, secret passage on Halloween night.

The lady disappears, the guests grow fearful, but then the hero climbs into the dark after her, finding her frail form crumpled and faint from a fall. Love ensues; Halloween triumphs.

By the 1890s newspapers like the Hartford Daily Courant announced Halloween events under their "City Briefs" sections. Magazines printed Halloween recipes, decorating ideas and games.

The norm was "quiet home parties in recognition of the quaint customs of days gone by," as reported by the Atlanta Constitution. Most of America had now heard of Halloween: lt was an occasion for a party.

Invitations to Halloween parties had to foreshadow the fun to come. Some innovative hostesses left jack-o'-lantems on the doorsteps of their guests, each bearing an invitation.

Others sent tiny boxes containing a handmade witch, with the invitation wrapped around her waist.

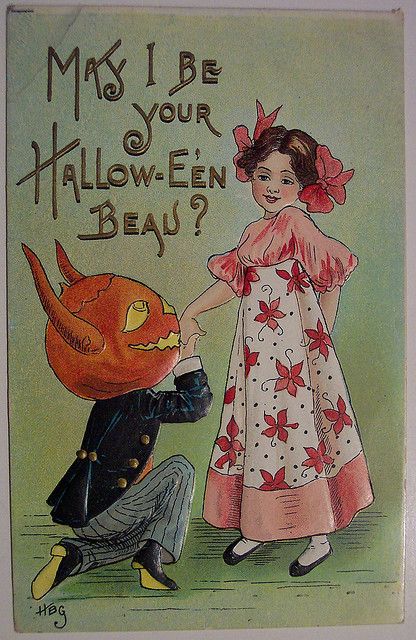

As Victorian ladies were expected to be handy with crafts, most Halloween party invitations were handmade in the shape of Halloween symbols and featured a rhyming verse.

The first Halloween parties, like any young people's party at the turn of the century, were used often for matchmaking.

As one Halloween story attests, special care was taken to ensure that guests were able to present themselves as favorably as possible, and that there was ample opportunity for romance:

A splendid bonfire was soon in operation, and the party danced around it. The sight of the flames was extremely becoming, and the young ladies had never appeared to such advantage before.

At all parties, but especially at Halloween, a highly dramatic entrance was a must. The party-giver's house was completely dark, lit only with jack-o'-lantems, fireplaces or, in some cases, long snakes made of tin and fastened above a light, whose heat made the serpent writhe.

Cornhusks decorated door knockers and silent, dark-robed figures led the guests to the cellar, the kitchen or some other darkened room before they could remove the wraps.

Some hostesses greeted their guests with an old elbow glove filled with sawdust; others, with active decorations such as tall hanging ghost or monstrous cobwebs made of yarn.

Yellow chrysanthemums were suggested for table decor in the advice columns of early 20th-century magazines, and use of these flowers was reported in the society pages of the same.

Autumn leaves, cornstalks and berries adorned party rooms, and open doorways were accented with dangling apples and horseshoes.

Halloween party guests dined on nuts served in fresh cabbage shells, brilliant half-pumpkins piled with apples, purple grapes and pears, and chicken salad in hollowed-out tumip shells. Some hostesses served Scottish scones; some opted for New England's Indian pudding.

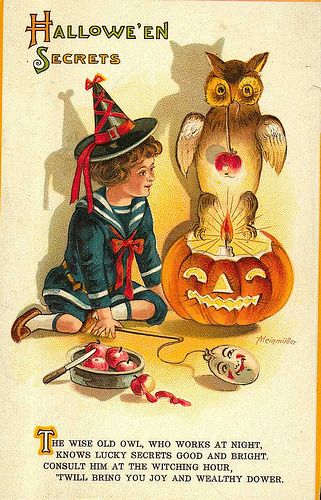

Victorian parlor games drew on all of history, unearthing traditions that probably hadn't been used for centuries, such as jumping over a candle flame.

The Welsh had purportedly jumped the Samhain fires and boys in England had long ago leapt over bonfires at Midsummer's Eve. Now the Victorians, with full dress trains and tight, hitched-up pants, were jumping over candle flames to determine their luck.

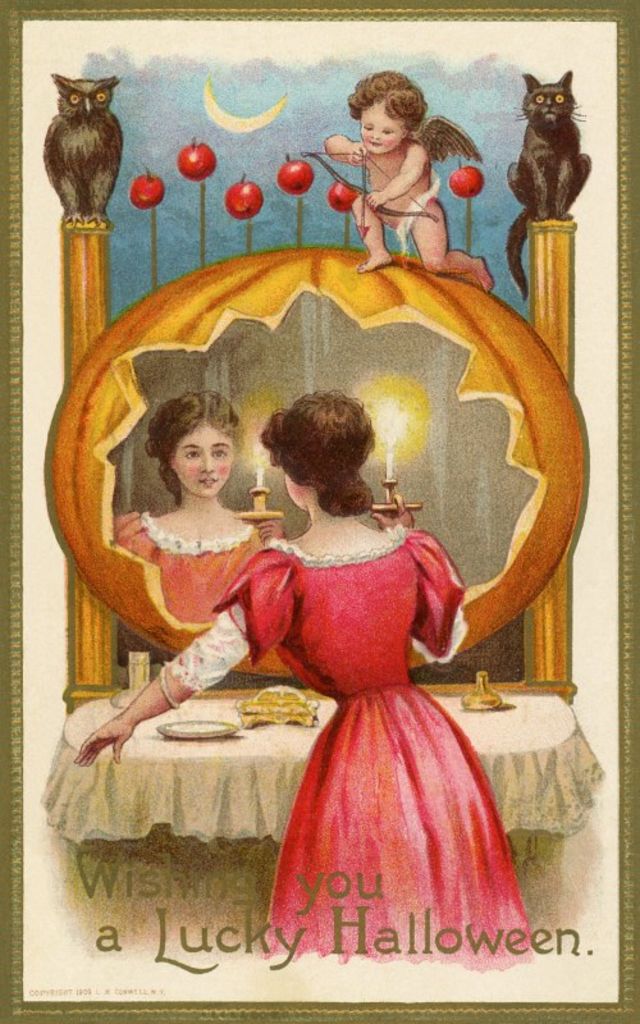

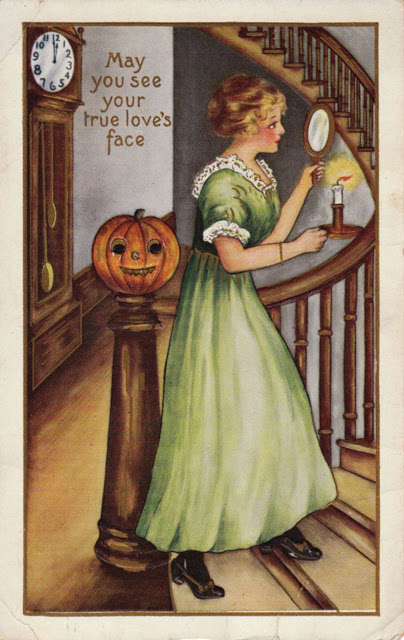

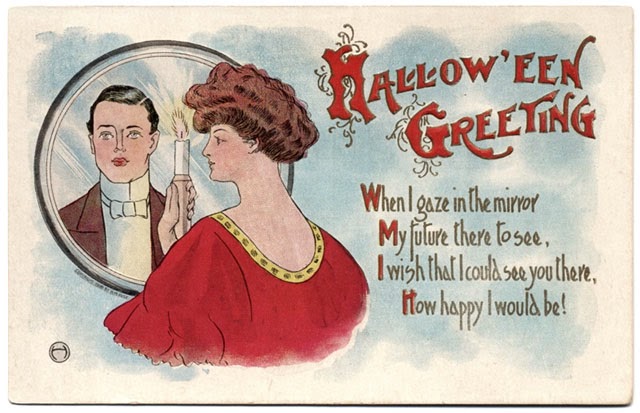

Parties included bobbing for apples, burning nuts in the fire, mirror divinations, snap-apple, apple paring and the test of the three bowls. But there were also many innovations, such as a hodgepodge of futuring games.

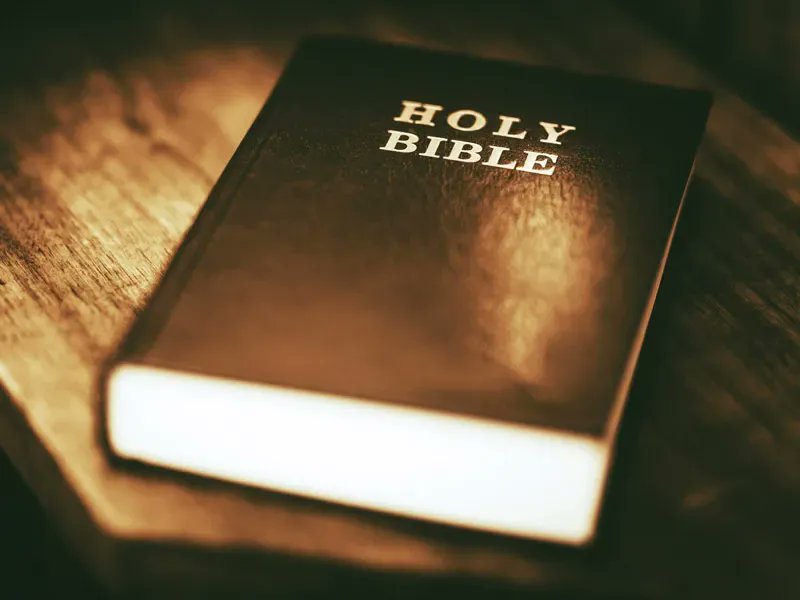

Maidens very anxious to know something about their future husbands will do well to try the Bible trick. lt's a good, old-fashioned and very popular trick. Take a Bible and place a key in it, leaving the ring protruding.

While the Bible is being supported by the little fingers of two boys or girls recite these words: "If the initial of my future husband's name begins with 'A' turn, key turn."

SlowIy repeat the letters of the alphabet, and when the right initial is reached the key will swing around and the Bible fall.

Storytelling contests around the fire were given a new edge by combining the tales with an old counting-off game. Guests each took a twig and set it burning, at the same time telling an impromptu ghost story.

Old Halloween games were given new twists and those new twists spawned new games, until many Halloween parlor games had absolutely nothing to do with the holiday.

In a "Halloween weight test," guests were weighed and each number in the weight was assigned a fortune.

"Kissing the Blarney Stone" was a game in which blindfolded guests had to try to kiss a white stone set on a table.

Young Victorians tried to bite of bags of candy hung by threads from chandeliers or doorways, and bobbed for apples using forks dropped from their full height rather than using their teeth.

They carved initials on pumpkins, blindfolded each other and tried to stick a pin in an initial to determine the name of their future mate.

They set tiny walnut- shell candle boats afloat in a tub of water and predicted the course of their lives based on the movements of the fragile vessels.

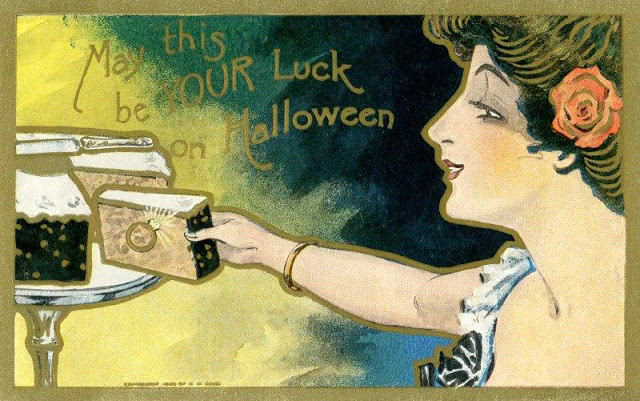

A popular game was the Halloween pudding. In this game, the host would bake a fruit cake with five objects hidden inside – a ring, a coin, a thimble, a button and a key.

At 9pm, the oldest person would silently cut the cake and gave the pieces. The first words spoken after the cake was cut would be prophetic for the year.

Person getting the piece with the ring would get married that year, the coin would be wealthy, the button meet their love, the key go on a journey, and the thimble be an old maid/bachelor.

Another game involved a single woman going alone into a darkened room with a mirror and a candle. She would take an apple with her and try to peel it all in one piece, or slice the apple.

It was believed your true love’s face would appear in the mirror. If you were going to die that year, a skull would appear.

Then there was a game where young women would go one by one into a dark room, which was claimed to be haunted, with a chest of drawers with boxes in them. They would then to go into the room in silence and collect a box from the drawer without screaming.

In a never-ending attempt to throw a better party or find something new to do, party hostesses added details to their celebrations that confounded the holiday's purpose.

On October 31, 1897, in a letter reprinted from the Philadelphia Times, the Atlanta Constitution reported the use of mistletoe as an October 31st tradition.

In the late 1800s, there was a move in America to mold Halloween into a holiday more about community and neighborly get-togethers than about ghosts, pranks and witchcraft.

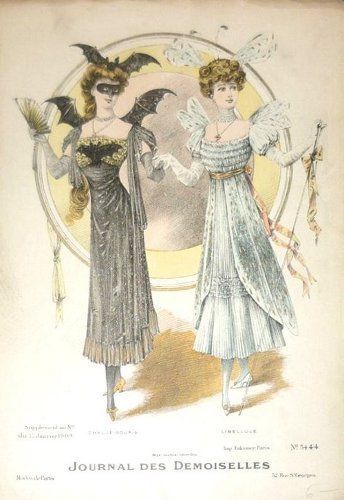

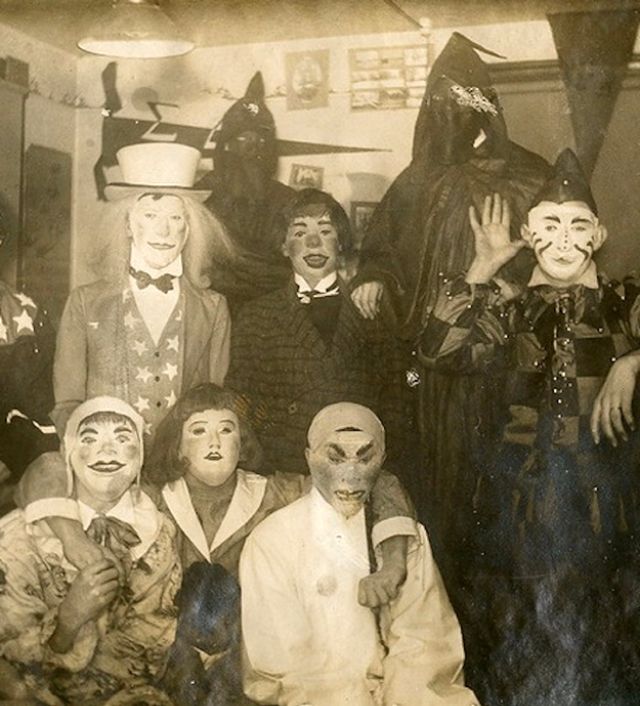

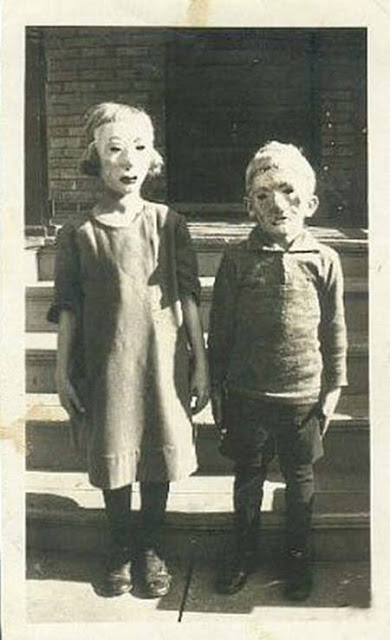

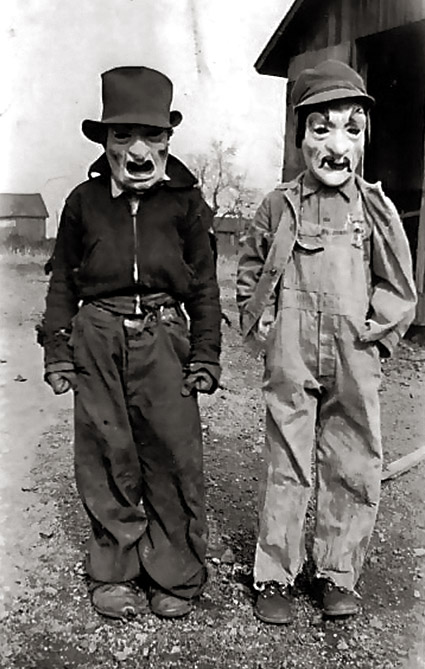

At the turn of the century, Halloween parties for both children and adults became the most common way to celebrate the day. Parties focused on games, foods of the season and festive costumes.

Parents were encouraged by newspapers and community leaders to take anything “frightening” or “grotesque” out of Halloween celebrations. Because of these efforts, Halloween lost most of its superstitious and religious overtones by the beginning of the twentieth century.

Popular theme parties appeared in the early 1900s. Young people gave Cinderella parties on Halloween, Black Cat parties even parties with a Mother Goose theme.

The November 5, 1898 edition of the Western Mail describes a Halloween tea held by a young lady by the name of Anna Leighton. Miss Leighton is reported to have invited sixteen of her female friends to “an early candlelight tea.”

The guests arrived to find the Leighton’s parlor decorated with autumn leaves, fruits, nuts, and ears of corn. There were jack-o-lanterns arrayed on the mantel and candles burning under crepe paper shades.

Wax candles illuminated the table and, beside every place setting, there was a cluster of red and yellow roses tied with ribbons and accented with a “silver horsehoe stick-pin” that could be taken home as a souvenir.

In keeping with the holiday theme, the menu for the Halloween tea consisted primarily of “nuts, fruit, and candy.” The guests were also served “fancy cakes” and ices which contained “either a needle, thimble, dime, or ring.”

After an evening of tea drinking and marriage forecasting, the young ladies at Miss Leighton’s party gathered around a coal fire and roasted marshmallows. They then told ghost stories.

Although Halloween disguises were still a novelty at adult parties as late as 1900, they gained popularity during the first decades of the 20th century. Halloween pageants and spectacles were also included by clever hostesses of the time:

"It was announced that couples should form for a grand march. A goblin bowed to a queen of hearts, a clown to a nun, and just as fancy seized them, gay and sober, joined hands to trip together a merry two-step

in and out of the rooms, through door and portieres, a line of fantastic figures. The music changed to a lanciers; the eight ghosts formed, the rest as they happened to be together, and all went through the figures in a way that would have amazed the originators of that dance."

Borrowing from European traditions, Americans began to dress up in costumes and go house to house asking for food or money, a practice that eventually became today’s “trick-or-treat” tradition.

In the early years of the 20th century new traditions emerged such as town-wide Halloween parades, which served an American culture that was growing more diverse, democratic, and populist.

Jack o’lanterns became increasingly popular so that by the 1920s carving pumpkins had become a tradition embraced by most Americans, which then also made its way overseas to Great Britain and resulted in farmers growing special pumpkins for pumpkin carving.

In addition, Halloween parties, costumes, and “trick or treating” that make up Halloween festivities today in America and Great Britain, did not actually become the norm until the 1930s.

The End

The End

Thank you for reading until the end! This was the last thread of this Spooky Month. I hope you enjoyed this thread, as well as the others.

Happy Halloween!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter