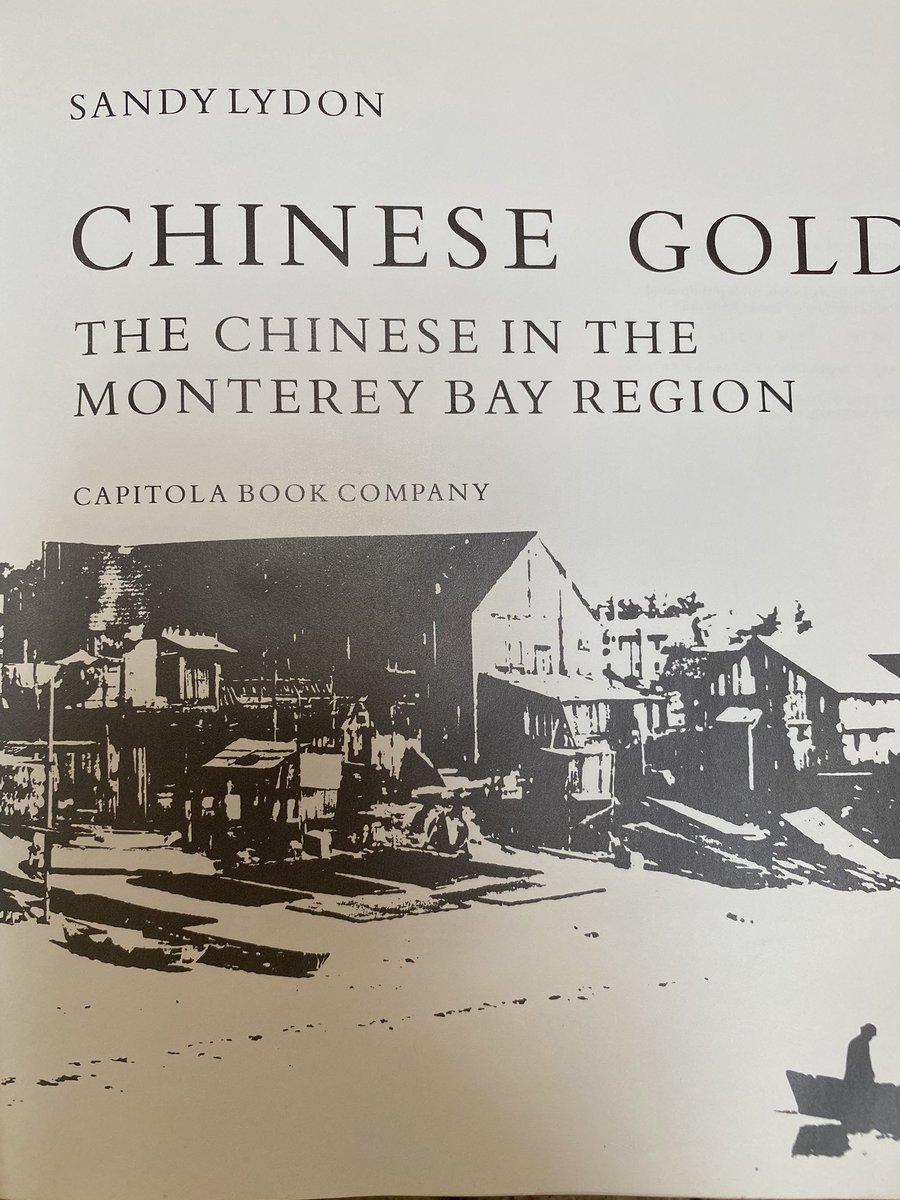

Picked up this out-of-print 1985 treasure of scholarship on the cultural/labor history of #MontereyBay by Professor Sandy Lydon, Historian Emeritus @CabrilloCollege. Won Book of the Year, Association for Asian American Studies, research supported by @sjsu. http://www.capitolabook.com/chinese.html

“Driving Highway 17 north of Santa Cruz, you will cross the dark and deserted Laurel-Glenwood tunnel and the sounds of the Chinese tunnel crews, the ring of the sledge, the explosions, will haunt you for miles.” p9.

“...In the sloughs around Watsonville and Salinas, you will see Chinese in the waist-deep mud digging out the willows and tules, turning swamp into prime agricultural land... The entire Monterey Bay region is a monument to the Chinese. This book is intended to help you see it.”

“Until their arrival in the 1860s, wheat was the dominant crop. The sugar beet industry which led an agricultural revolution in both the Salinas and Pajaro Valleys was built on the backs of the Chinese.”

“At the turn of the century the Chinese helped pioneer the fruit-drying industry which made the difference between profit and loss on the apple crop..“

“In Monterey where Cannery Row is now a tourist attraction, the Chinese founded the commercial fishing industry.. #SantaCruz became a resort town because Chinese made cuts, drilled the tunnels, & laid the rails which brought the trainloads of tourists to @sccounty / @SeeMonterey.”

“The strongest hint of the early Chinese contacts along the California coast is found in the legendary history of the land of Fu-Sang. In 499 a Buddhist monk named Hui-Shen returned to China and recounted his visit to a land called Fu-Sang which lay east of China.” p14

“One of the few histories of California to dwell on the subject of early Asian contacts by sea is Charles Chapman’s History of California the Spanish period, published in 1921. Chapman indicates that for some Chinese & Japanese sailors the problem was not how to make the journey,

..but how to avoid making it, as the black tide could easily drag even the cautious sailor & his craft over the horizon. During the Spanish colonial period, there is said to be an authentic record of 60 craft [from Asia] driven across the Pacific in the 18th & 19th centuries.”

In 1774, when Juan Bautista de Anza saw Carmel Bay, “he saw a strange wreck, of a construction which none of the Spaniards there had ever seen... Eventually, the sketchy physical evidence of early contacts by Asian sailors became intertwined with the story of Fu-Sang.” p15

The Spanish colonial administrative unit was connected by clockwise currents & winds. “Spain dispatched a single annual ship to make the Pacific loop and deliver a years worth of directives letters and payroll...

From 1565-1815 the ship’s annual voyage tied the Philippines to Mexico City, capital of New Spain. On the Acapulco-Manila leg the galleon was loaded with Peruvian & Mexican silver which traded in Manila for goods from all over Asia; particularly Chinese silks, porcelain jewelry.”

“Designed and built by Chinese craftsmen in Manila, crewed in part by Chinese sailors, the Manila galleons were known as

*naos de China* - China Ships.” p17

*naos de China* - China Ships.” p17

“To return to Acapulco from Manila, the galleon sailed due north into it caught the marine conveyor belt, the Kuroshiro current, which carried it across the Northern Pacific to the coast of North America. Upon sighting the California coast...

the galleon turned south and ran before the prevailing northwesterly to Acapulco. The ship was often out of sight of land for 6 months on the eastward journey, and the crew usually caught beri beri or scurvy long before reaching Acapulco. It was not unusual for half of the crew..

..to be incapacitated by the end of the voyage, and in one particularly ill-faded instance, the entire crew died on the return ship and the galleon was found drifting of Acapulco filled with *silk and cadavers*”.

“The return voyage of the galleon so tested human endurance that in 1602 New Spain sent Sebastian Vizcaíno north from Acapulco to find a harbor which the galleons might use as a place to refit take on freshwater and food for the last leg of the trip down the coast...”

Vizcaíno selected the oval shaped depression between Punta de Año Nuevo & Punta de Pinos as the best available harbor naming it after the Viceroy of New Spain, the Conde de Monterey.”

“Soon after Vizcaíno returned with the news of his discovery of a perfect haven for the China Ships at Monterey, the Spanish bureaucracy was distracted by other international concerns, and for 160 years more, the China ships sailed down the California coast.”

“Monterey had grown to be such an ideal harbor in the imagination of the Spanish that once Portola‘s expedition finally came north to the site in 1769, “the best part that could be desired” did not fit the reality of Monterey’s open roadstead.” p18

“The plan to make Monterey the harbor of refuge for the China Ships had gained such bureaucratic momentum that even when one of the greatest natural harbors in the world was discovered nearby at San Francisco...

..the Spanish tenaciously stuck to the original plan of making Monterey the capital of the province & harbor for the galleons from Manila..

Monterey never became a regular harbor of refuge for the galleons, but a half dozen of the China Ships stopped there between 1769 and 1815.”

Monterey never became a regular harbor of refuge for the galleons, but a half dozen of the China Ships stopped there between 1769 and 1815.”

“most Galleon captains preferred to stay out to sea and make the final run to Acapulco rather than risk either the shallow harbor or the rocky coast nearby.”

“A large number of Chinese merchants found their way to Mexico via the galleons and over the years & had taken the necessary steps to become citizens of New Spain.

When the colonial system spread to Alta California some who came north were ethnic Chinese or Spanish chinos.” p19

When the colonial system spread to Alta California some who came north were ethnic Chinese or Spanish chinos.” p19

“The first documented Chinese resident in the Monterey Bay region was Annam, a native of a village six miles from Macao in Kwangtung Province... who was employed as cook for Pablo Vicente Sola, the Governor of Alta California.” (~1815)

“One other tantalizing Chinese remnant -Arroyo del Chino- ravine of the Chinese, found on old deeds. Given to the ravine near present-day Aptos cut by Aptos Creek on its way to the sea, the name dates from when Rafael Castro was granted the Aptos Rancho by the Mexican government.

The only Chinese listed in either Monterey or Santa Cruz County in the 1850 census lived in the house of Rafael Castro, next to the Arroyo.

The handwriting on the manuscript census appears to be Sanquie (San Kee?).” p20

The handwriting on the manuscript census appears to be Sanquie (San Kee?).” p20

“scattered references to Chinese in the Monterey Bay area before Alta California became part of the United States in 1848 are probably a fair representation of the extent of the Chinese presence. The local Indians provided the raw [sic? forced?] labor for the agriculture...

.. and there was little commerce to attract Chinese merchants to Monterey because the Spanish & Mexican governments had severely restricted commerce along the Alta California coast.

But circumstances were permanently altered by unrelated events on opposite sides of the world...

But circumstances were permanently altered by unrelated events on opposite sides of the world...

Unrest in Kwangtung Province

and the California Gold Rush.

and the California Gold Rush.

*Kwangtung is known today as Guangdong.

Economic and political dislocation brought in part by British military activity around **Canton (**Guangzhou) in the 1840s increased pressure on the people of (Guangdong).”

Economic and political dislocation brought in part by British military activity around **Canton (**Guangzhou) in the 1840s increased pressure on the people of (Guangdong).”

“Revolt and civil war raged in the late 1840s and 1850s, and many families...sent sons and husbands away to supplement income or reduce the number of mouths to feed... (many) headed for California - *Gum Shan* - the Golden Mountain.

California was the Golden Mountain not because there was gold, but because there was the opportunity to transform so many different things into wealth.

Clumps of willow meant a swamp to the Yankee, and each farmer had a “worthless” section of “willow land”... grumbled about, and ignored... But to the Chinese the willow was a symbol of life and regeneration.. a clump of willows indicated freshwater and fertile land.” p24.

“The Gold Rush in the Sierra Nevada instantly realigned California geography, erasing the legacy of Vizcaíno & a harbor of refuge for the China Ships. The route from San Francisco to the Mother Lode became the most important area in California; Stockton & Sacramento flourished.”

“Monterey lost the capital.. rather than try to wretch the land.. away from its Mexican inhabitants... the impatient Yankees moved the capital to a new site where there were few Mexicans, and where opportunities were not stifled by complicated Mexican land grants...

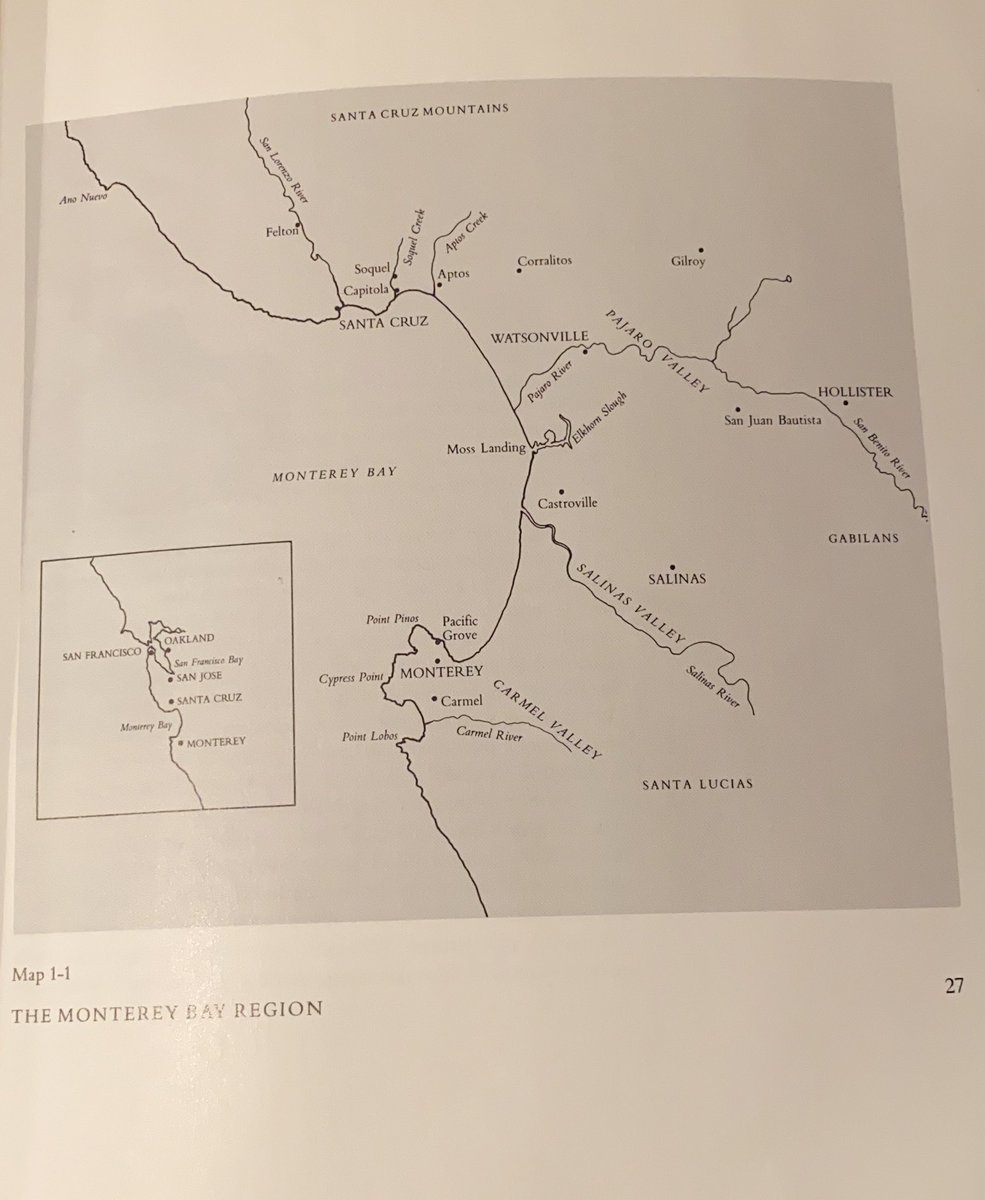

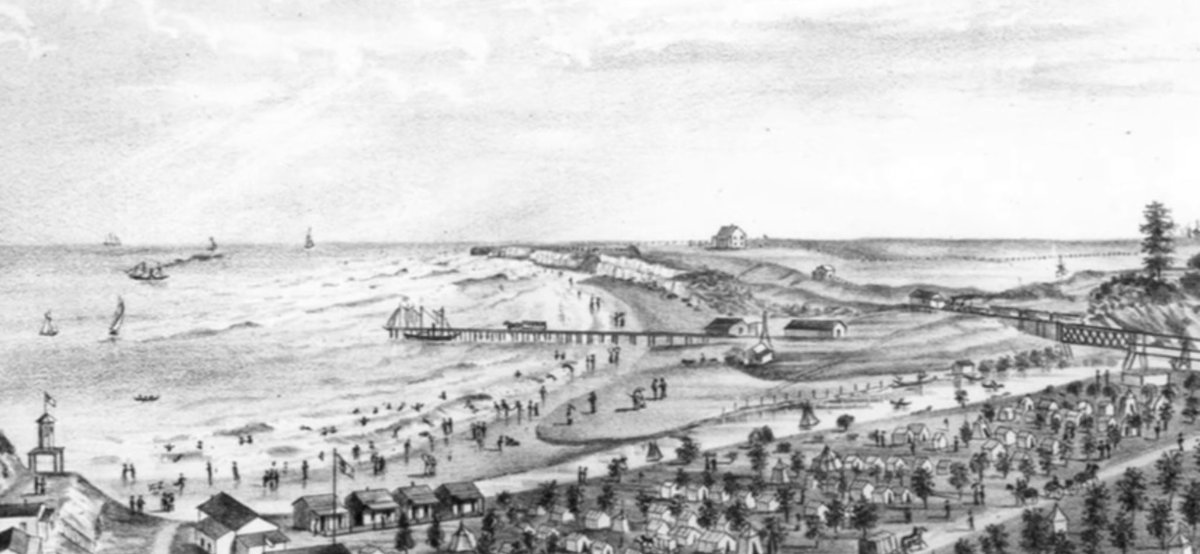

On the north side of Monterey Bay, a knot of Yankees was turning #SantaCruz into the image of #NewEngland. Neither Santa Cruz Mission or Villa de Branciforte were successful in converting Indians or attracting Mexican settlers so in the 1840s a vacuum filled up w/Yankee settlers.

By 1845 more Yankees and foreigners lived near Santa Cruz than anywhere else in Mexican Alta California...

By 1850, Monterey Bay was braced by two communities, a replica of New England on the north and of Mexico on the south.” p26-27

By 1850, Monterey Bay was braced by two communities, a replica of New England on the north and of Mexico on the south.” p26-27

“In the early 1850s while most Chinese immigrants boarded British sailing ships for the journey to the Golden Mountain, a half-dozen families set sail in small junks to follow the black current. The first Chinese colonists in the Monterey Bay area came directly from China by sea”

“The skilled and imaginative Chinese fisherman who set up fishing camps along the California central coast challenge the stereotype of the Chinese as mindless, machine-like workers who provided nothing but the labor for railroad or levee building.” p29

“Though evidence is circumstantial, it’s possible families who came directly to Monterey Bay were “boat people” or Tanka, a distinct minority group living along the southeastern coast. Boat people were treated as outcasts; prohibited from living onshore in the early 1800s.”

“fishing families spoke a different dialect of Chinese from that of the single men who lived in Monterey... these Chinese immigrants knew the value and potential of the sea. To a Chinese, the seashore is the best insurance against starvation.” p31

“Indians fished extensively for shellfish, salmon, & steelhead, prior to colonialization. Yankee otter hunters (with Mexican partners) worked up the coast killing otters for their pelts.. Abalone populations exploded, Inadvertently setting the stage for the abalone rush”

p32

p32

“The Spanish left us with the mollusks’ unusual name, which is either a variation on their Indian name Aulon or a “corruption” of the Spanish ‘orejones’ or ‘sea ears’..

in 1866 the Monterey County assessor declared the abalone supply exhausted between Monterey & San Diego.”

in 1866 the Monterey County assessor declared the abalone supply exhausted between Monterey & San Diego.”

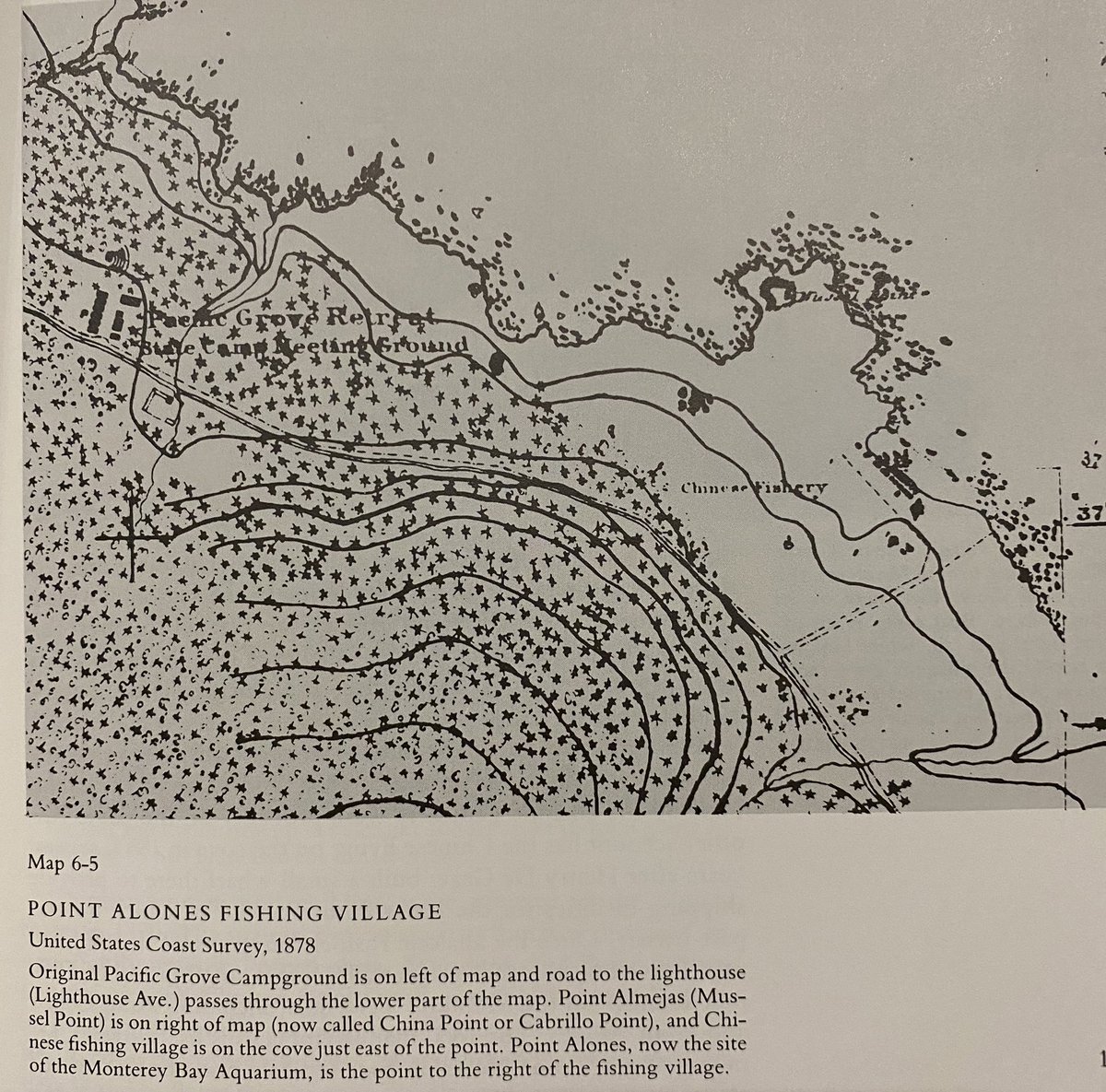

“In 1875 the three Chinese fishing villages near Monterey had 30 boats between them.. the largest vessel was a 12-ton junk used to transport fish and supplies.. between Point Alones and Pescadero.. The junk was a common site along the coast, raising suspicions of smuggling...

..in 1889 a United States officer staged a dramatic raid on the junk as it lay off Point Alones, and with visions of a hold full of opium, the officer stormed down into the junk’s hold only to find strong smelling dried fish.” (Point Alones is site of @MontereyAq / Cannery Row)

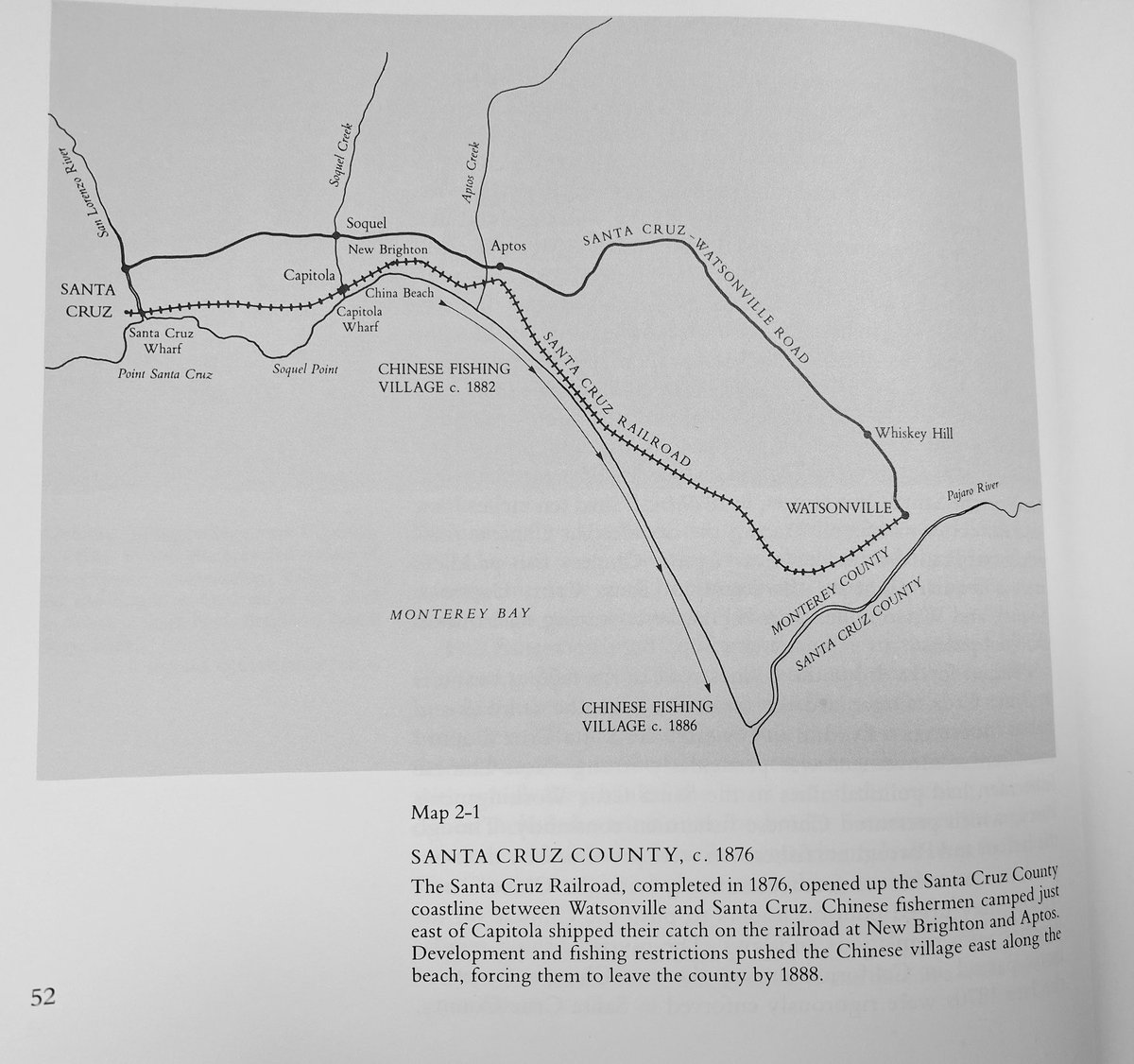

“When the railroad was completed 1875, a company of Chinese fisherman set up a permanent fishing camp on the beach just east of Camp Capitola and begin shipping boxes of fresh fish.. By 1878 over half of the fish caught in Santa Cruz County were by the Chinese near Capitola.” p49

China Beach was the name for the fishing camp at what today is New Brighton State Beach @CAStateParks.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Brighton_State_Beach

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Brighton_State_Beach

“Chinese who competed with whites were met with mobs and violence.. sportsmen complained to the California legislature, by the late 1870s it was illegal to catch trout with a seine... (violence &) political forces drove the Chinese out of the fishing business in Santa Cruz.” p51.

“Italian and Portuguese fisherman were prevented by their dependence on wharves from competing with the Chinese near Aptos, they urged political leaders to push the Chinese of beaches with regulations and laws...

The myriad of fishing regulations passed in California during the anti-Chinese frenzy of the late 1870s were rigorously enforced in Santa Cruz County though often ignored in Monterey. 1887 the Chinese made their last fishing camp in @sccounty at the mouth of the Pajaro River.”p51

“It seemed only a matter of time before the Italians, Portuguese, and anti-Chinese proponents in Monterey might drive the Chinese fishermen off the Peninsula..

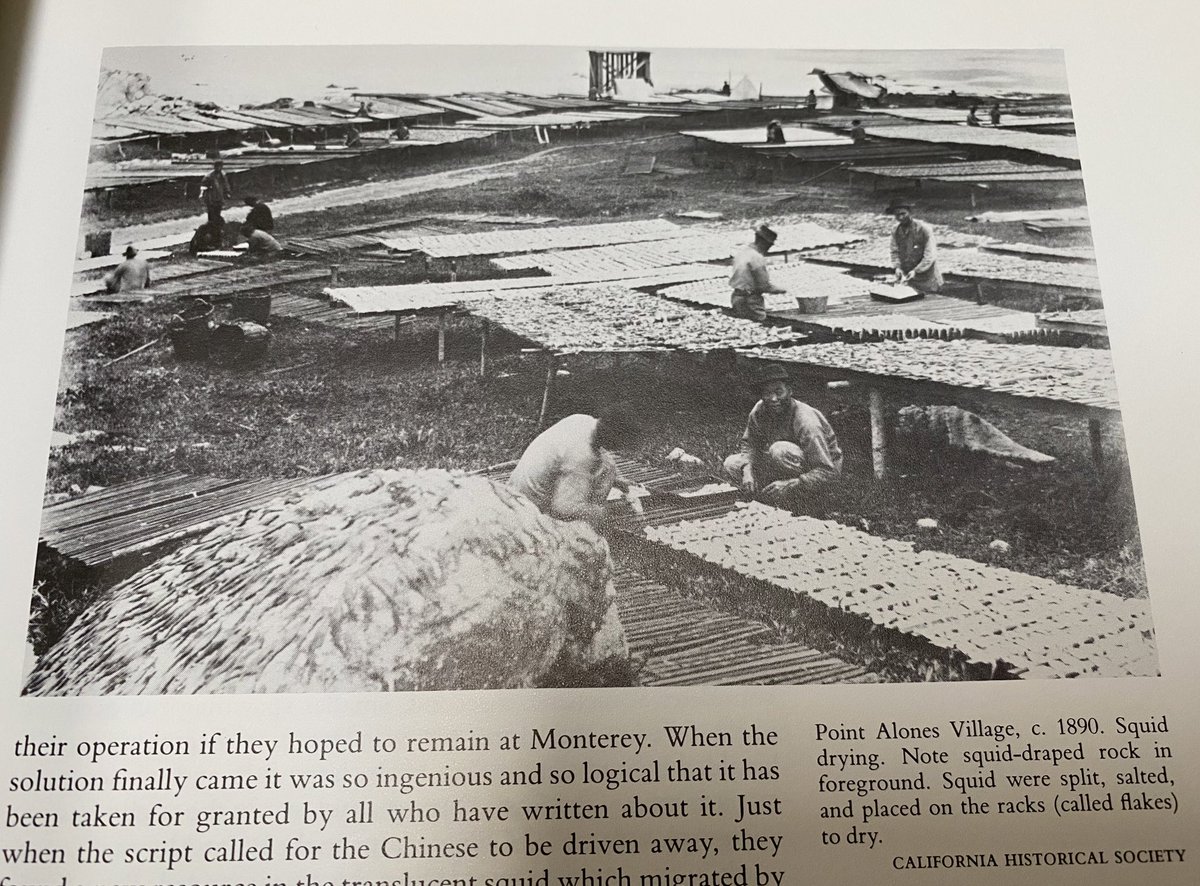

Just when the script called for the Chinese to be driven away, they found a new resource in the translucent squid..”p55

Just when the script called for the Chinese to be driven away, they found a new resource in the translucent squid..”p55

..Fisherman in China discovered years before that some species of fish were attracted to light suspended over water at night. Squid would eventually swim to the surface and surround the light, all the fishermen need to do is scoop fission to their boats...

..While Italian fisherman we’re home in bed sleeping, the Chinese caught squid and returned to Point Alones by daybreak to unload the squid and spread them to dry.. This gave new life and energy to Point Alones when many other Chinese fishing villages were dying out.” p56

“Interviews with descendants of the fisherman explain differences between split and cleaned squid, which were dried on flakes, and whole squid, which were dried on the ground.

Whole, poor-quality squid were packed into barrels in alternating layers of squid & salt. During the late 19th century the Chinese government had a monopoly on salt production in levied a high tax on it. The squid were imported as fertilizer but were really purchased as salt.”p57

“Squid arrived off Monterey in late April, remaining in the bay for two months before spawning cycle was complete. Sometimes a second, smaller run occurred in the fall; it’s beginning heralded by a phalanx of seabirds, large fish, and whales intent on partaking of the feast.”

“As the first canneries moved into Monterey in the late 1890s, and displaced the economic value of the squid, objections to the odor of drying squid reached a peak and eventually caused the end of Chinese squid fishing.” p59

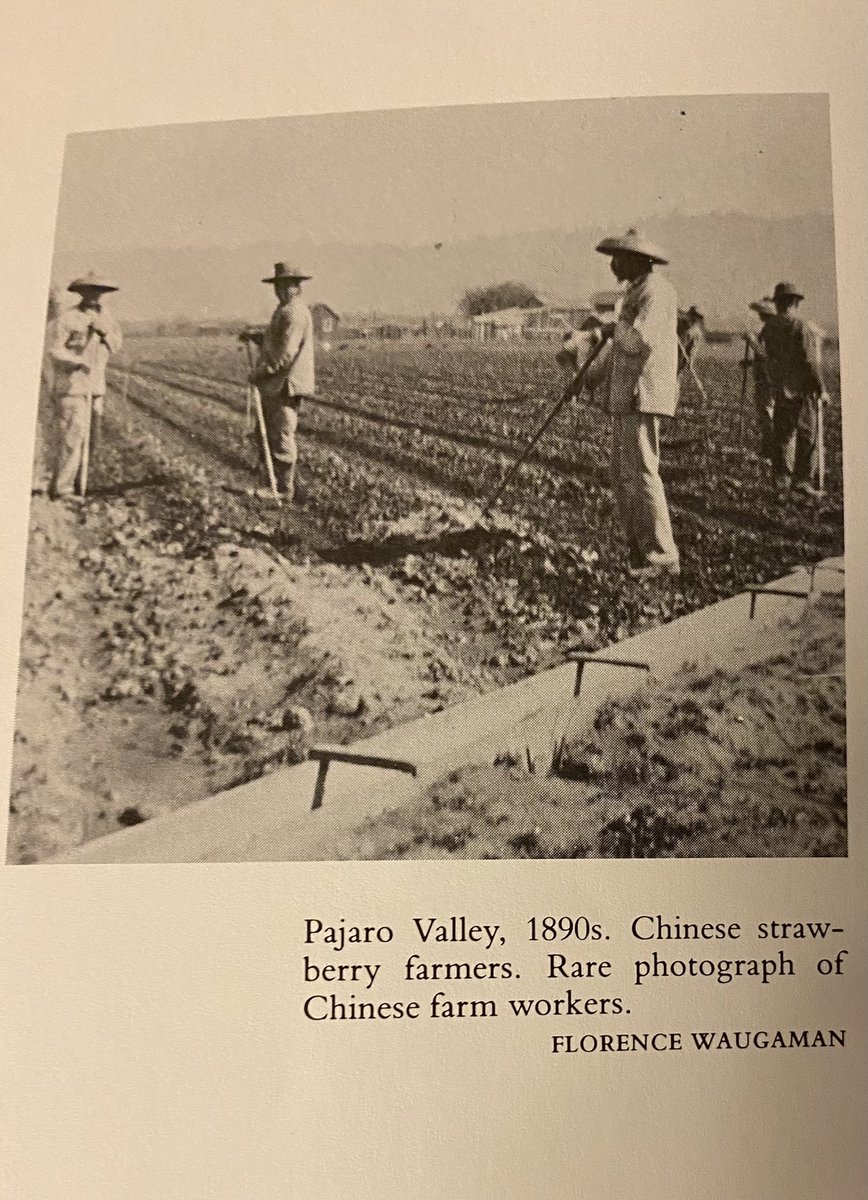

“1850-1860, the region was dominated by a single crop: wheat. When the first crews of Chinese farm laborers entered the region in the summer of 1866, they brought the same resourceful attitude toward working the land that they brought to harvesting the abundance of the sea.” p61

“from 1770 until the 1860s most of the field labor in Northern California was provided by California Indians. As late as the 1860s white labor contractors herded in bands of dispirited Indians through the valleys each summer to harvest the grain... Chinese farm laborers were used

extensively for the first time in the 1866 harvest. Many of the Chinese working the 1866-1868 harvests had been miners in the Sierra Nevada.. This pool of labor swelled in May 1869 when the Central Pacific Railroad released its construction crews.. Farmers introduced crops more..

labor intensive than wheat.. in 1869 the tobacco industry.. cigar making, boomed. Tobacco acreage spread from Gilroy to Hollister; the world’s largest cigar factory was in Gilroy, another near Hollister; Virulent lobbying against Chinese-made cigars put them out of business.” p64

“Mustard was introduced during the Spanish era.. quickly crowding out native grasses. Ranchers and farmers considered mustard a nuisance.. picturesque to travelers.. fields of mustard were seen as an opportunity for the Chinese... Working as a crew, they cut the mustard..

..spread it over a canvas, and beat it with flails to remove the seeds.. The first Chinese to exploit the value of wild mustard was “Poison Jim”.. a French mustard buyer (paid) $35,000 in gold.. farmers began to hire Chinese farm laborers to harvest the mustard.” p69.

“Sugar beets finally revolutionized agriculture in the Monterey Bay region..when the largest beet sugar factory in North America began operating in Watsonville in 1888. The industry brought profound changes.. including the establishment of an essential Chinese labor force.” p70

“The California Beet Sugar Company began when the first successful beet sugar plant in the United States was built in 1870 on the east side of San Francisco Bay in a place called Alvarado (now Union City) in Alameda County. In 1874, the company recapitalized and moved to Soquel.

..firewood and lime were plentiful, and the nearby Soquel Landing (Capitola wharf) facilitated shipping, and the route of the Santa Cruz Railroad (under construction 1874) would pass within 100 yards of the factory.

Most importantly, the factory could draw on some hundreds of acres of rich alluvial soil, both in Soquel Creek flood plain and the Pajaro Valley to the east... The first beet crops was planted on the alluvial plain surrounding the factory site (present the Capitola).

While assisting with the construction of the factory, Chinese farmers cultivated, thinned, and weeded sugar beets.. cut and loaded firewood for boilers, lifted and moved 180-pound syrup cans... and packed four tons of sugar processed per day..145 / 200 employees were Chinese.”p72

“To encourage farmers to grow sugar beets and to guarantee that there would be beets to crush each fall, the company offered contracts to the farmers before the crops were planted… This helped revolutionize the region’s agriculture; farmers sold their crop before it was planted.

This contract system is still in use. The farmers subcontracted the actual growing of the beets to Chinese labor contractors..

Later Watsonville became the sugar capital of North America thanks to the Chinese workers willing to bloody their knees in the fields.” p75

Later Watsonville became the sugar capital of North America thanks to the Chinese workers willing to bloody their knees in the fields.” p75

“During the 1850s the Santa Cruz area strawberry fields were contracted out to Chinese market gardeners... Later, Irrigation, together with the surplus of Chinese farm laborers, freed up by the collapse of the Soquel sugar beet factory, saw strawberry acreage to jump by 1885...

Each year the transformation of the region’s agriculture moved south & east. The Salinas Valley was undergoing a similar shift from wheat to more specialized crops. Chinese farm laborers were the catalyst for transforming a vast wheat field into the “salad bowl of the world.” p77

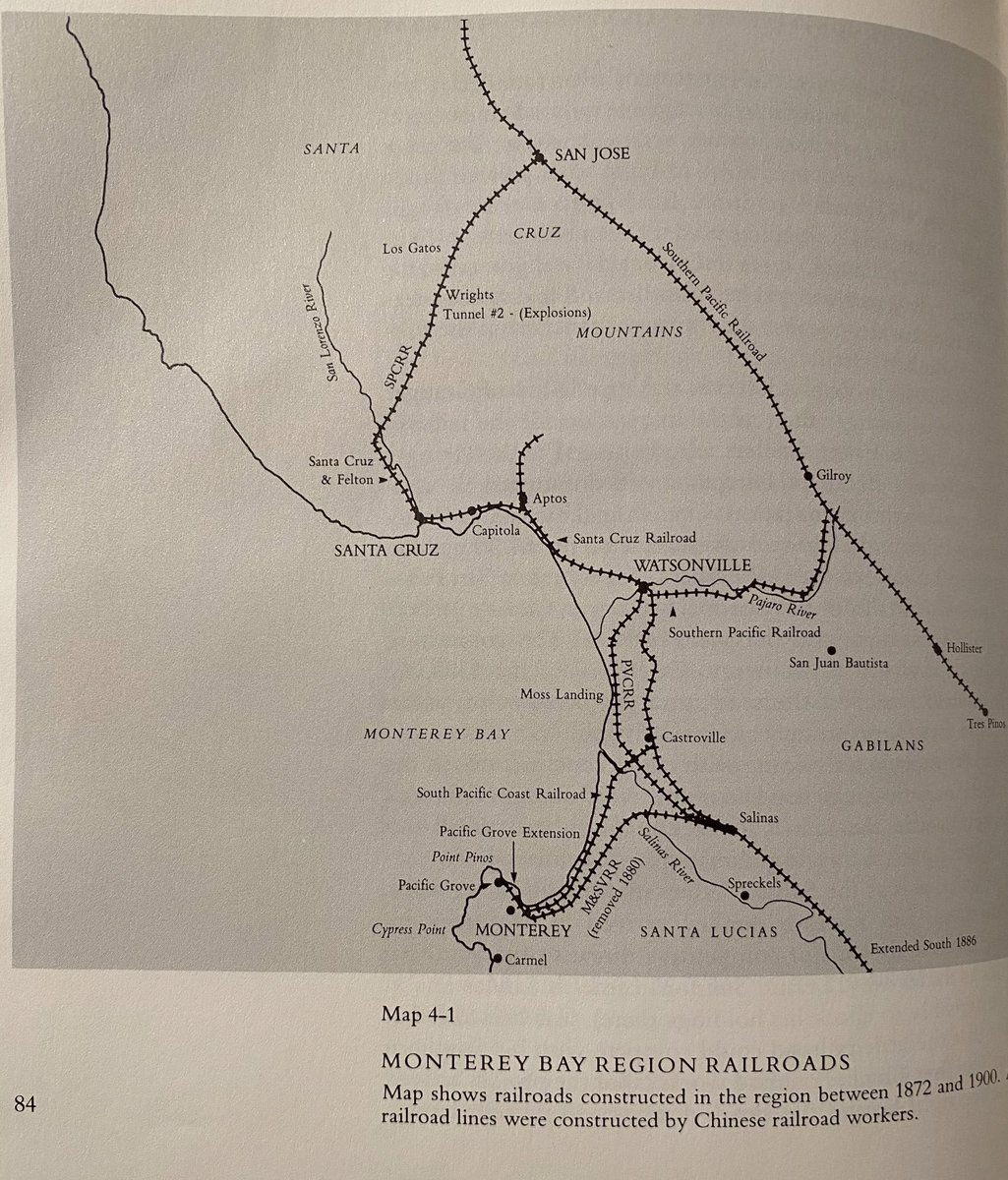

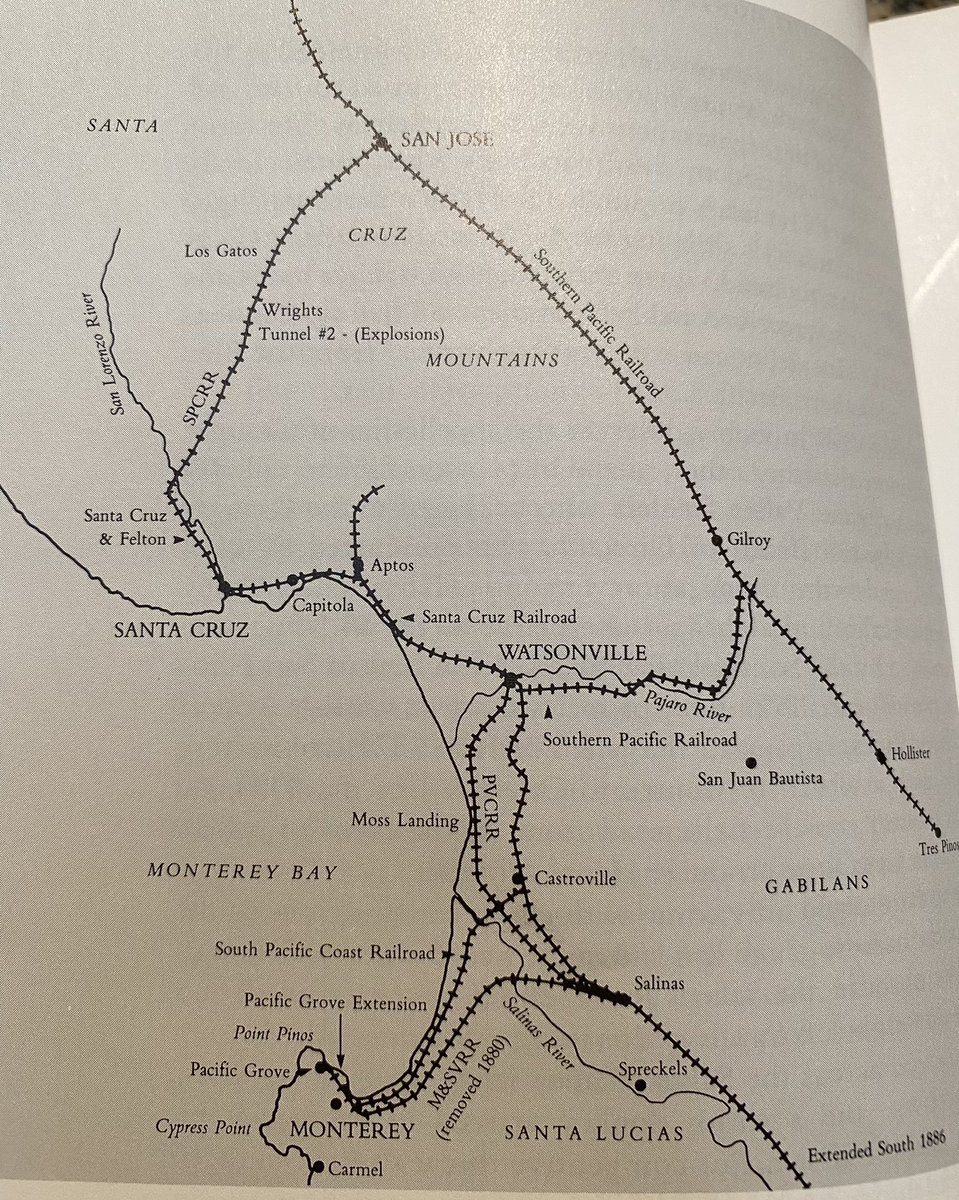

“When the Central Pacific and Union Pacific joined in Utah in 1869, the Central Pacific released an estimated 5,000 railroad workers who provided the labor for a decade of railroad building throughout California.

In 1870 there were no railroad tracks in the Monterey Bay region..

In 1870 there were no railroad tracks in the Monterey Bay region..

By 1880 Chinese railroad builders dug cuts, laid ballasts, drilled tunnels, built trestles, laid track, and risked death to build almost 100 miles of track, bringing Santa Cruz and Monterey counties into the industrial age.

Isolated by natural barriers, fragment to be difficult terrain such a sloughs, swamps, and mountains, the Monterey Bay region was unified by the railroads and connected with the outside world.. transformation was made possible by the courageous Chinese railroad workers risking...

life and limb to build the roads under seemingly impossible conditions - drilling over two miles of tunnels through the Santa Cruz Mountains during the construction of the South Pacific Coast Railroad, or pushing..through the tortuous Aptos Canyon for the Southern Pacific.” p.80

“During the Civil War Chinese Railroad crews pushed the railroad south from San Francisco to San Jose, opening in 1864; extending to Gilroy in 1869; with the completion of the Transcontinental railroad, owners wanted route south from San Francisco and Sacramento to give them..

..a monopoly on rail traffic in California. Southern Pacific pushed the railroad through the Pajaro Gap and into the Pajaro Valley, reaching Salinas in 1872 to tap the wheat-rich Salinas Valley.. replacing freight wagons that carried increasing amounts of wheat to Moss’s Landing.

Most of the Chinese working on the Salinas extension were veterans of the Transcontinental, and laying down rails through the Pajaro Valley and into the Salinas city was easy by comparison.”p82

“But the boom the Southern Pacific brought the Salinas Valley quickly lost its luster... extortion of right of ways, depot acreage, decisions about routes and schedules shrouded in secrecy, a cavalier attitude about setting rates, the Southern Pacific aroused animosity..

Encouraged by Salinas Valley farmers eager to find a cheaper alternative than shipping wheat to San Francisco, two influential Monterey property owners organized the Monterey & Salinas Valley Railroad in 1874, connecting Salinas with a wharf in Monterey.

The Monterey & Salinas Valley railroad was the first of several proposed Granger railroads constructed in central California. The Grange was founded in the Midwest in 1867 as a farmers protest against railroad abuses, and by 1874 a unit of the organization was active in Salinas.

1/3 of the $300,000 capital used to construct the road came in the form of a loan from Santa Cruz lime producer Henry Cowell.

Leland Stanford came to Salinas late in April 1874, and scoffed at the idea that the little railroad can compete with his Southern Pacific.

Leland Stanford came to Salinas late in April 1874, and scoffed at the idea that the little railroad can compete with his Southern Pacific.

By May, 150 Chinese were cutting the grade between between Monterey and Salinas. Throughout the next 7 months the railroad tried to supplement it’s construction crews with white laborers, but few came forward for the arduous work, so the Chinese provided the bulk of the labor..

Upon completion, the 18.5 mile granger railroad became celebrated throughout California.

*Monterey county has solved the problem of how to cut loose from the grinding extortions of the railroad monopoly,

*Monterey county has solved the problem of how to cut loose from the grinding extortions of the railroad monopoly,

their little narrow gauge railroad has taken the kinks out of a small section of Stanford’s line.. and made the people of that locality no longer depending upon the wheel in pleasure of the Railroad King* p84.

The Salinas River trestle proved to be the railroads’s undoing. A flood in January 1875 swept it away and it took Chinese crews two months to get the railroad running again.. The trestle went down again the following January, this time for six months..

Unable to make payments on the construction loan, in December 1878, Henry Cowell foreclosed on the railroad, driving it into bankruptcy.

Leland Stanford and the Southern Pacific paid their final respects, by buying the Monterey & Salinas Valley Railroad at auction.” p87

Leland Stanford and the Southern Pacific paid their final respects, by buying the Monterey & Salinas Valley Railroad at auction.” p87

“If 19th century Monterey County owed much to the coming of the railroad, Santa Cruz County owed everything.

Until the mid-1870s the tiny settlements along the coastal terrace were temporary beachheads isolated by a beautiful, but convoluted landscape..

Until the mid-1870s the tiny settlements along the coastal terrace were temporary beachheads isolated by a beautiful, but convoluted landscape..

Winter storms often trapped residents of Santa Cruz between impassible creeks and mountains and one side and southwestly gales and mountainous seas on the other. In the 1860s it was not unusual for the county to be out of contact with the outside world for weeks at a time.

The road between Santa Cruz and Watsonville was so precarious that during the smallpox epidemic of 1868, some Santa Cruz citizens attempted to isolate the disease in Watsonville by destroying the bridge across Aptos Creek.

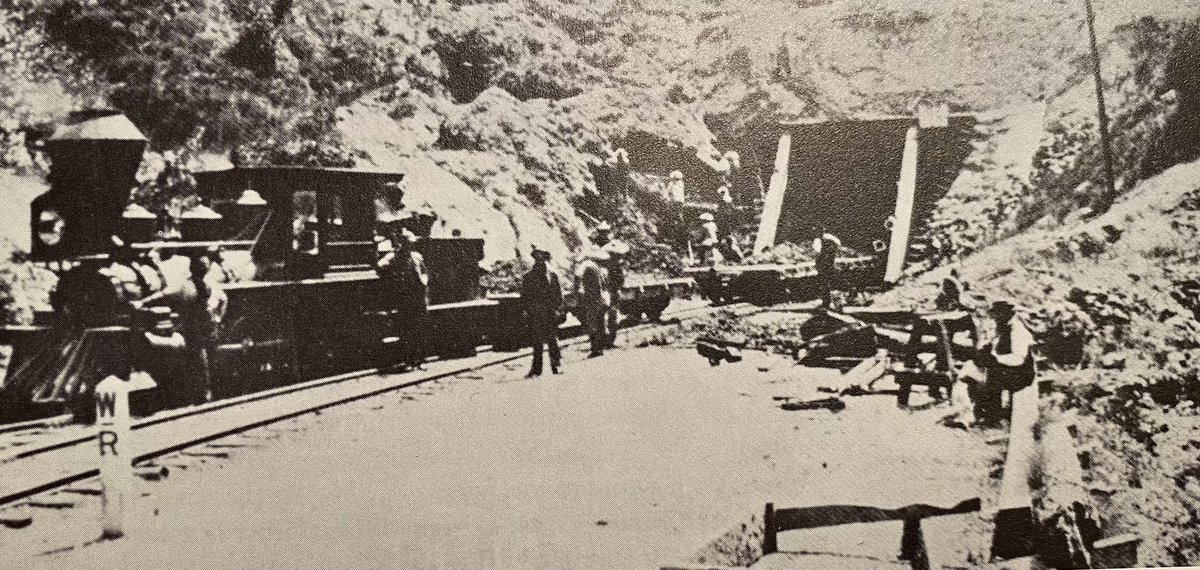

Between 1875 and 1880 the Chinese built three separate railroads, laid 42 miles of track, and drilled 2.6 miles of tunnels to stitch Santa Cruz County together and attach it permanently to the world beyond the Santa Cruz Mountains.

At least 50 Chinese were killed in accidents while building those railroads.

For every mile of railroad, one Chinese died.

For every mile of railroad, one Chinese died.

The 1st railroad on the north side of Monterey Bay was a tenuous narrow gauge connecting the San Lorenzo River Valley and it’s redwood and lime deposits with the wharves of Santa Cruz.

In 1874, the Santa Cruz & Felton railroad opened, eight months after Chinese railroad workers started the eight-mile line, engineered around rocks and trees. Lumber cut in the canyons was loaded onto an amazing 14-mile flume that shot each board to the Felton railhead.”p.89.

“Early efforts to coax the railroad over the Santa Cruz mountains failed; in 1872 businessmen watched with disappointment as the Chinese crews working for the Southern Pacific came through the Pajaro gap and turned south toward the Salinas Valley rather than north into @SCCounty.

Local businessmen, including Claus Spreckels and Frederick Hihn organized their own railroad, and with the aid of a subsidy approved by the county voters, began construction of the Santa Cruz railroad in December 1873.

Despite the anti-Chinese movement which gripped Santa Cruz at the time, most of the construction was done by Chinese. Chinese railroad workers worked six ten-hour days a week and were paid one dollar a day, with two dollars subtracted each week for food.” p 91.

“Even on the relatively straightforward Santa Cruz Railroad, work was dangerous business. In April 1876, months before the railroad was completed the brakes failed on a construction train and it plowed into a group of Chinese working on the railroad. killing one, injuring others.

The next month, the bank of a railroad cut fell onto Chinese workers, breaking their legs.. The most melancholy accident on the Santa Cruz Railroad occurred in January 1876 when a construction train ran over a Chinese worker mangling his legs.. against all odds he survived.”

“The dream of a railroad over the #SantaCruzMountains to San Jose had tempted Santa Cruz businessman since the early 1860s.. construction costs for a railroad through the mountains would be extremely high, and would be in direct competition with the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Senator James Fair was not awed by the challenges.. with his briefcase filled with Comstock mining money, Fair incorporated and begin construction of the South Pacific Coast Railroad (SPCRR) in 1876.

Compared with the soaring majestic Sierra Nevada, the Santa Cruz Mountains are small and round, covered with redwoods and douglas fir. On closer inspection, the Santa Cruz Mountains are dark, brooding, mean little mountains, twisted and gnarled by faults..

Fair decided to go through the mountains rather than over them... the route included a 6,243 foot tunnel at the summit and a 5,325 foot tunnel between Laurel and Glenwood. Tunnels leveled out the grade so the narrow gauge would be able to operate safely and efficiently.

Chinese did all the grading, tunneling, track-laying, and ballasting.. by 1879 approximately 1,000 Chinese railroad workers worked in the Santa Cruz Mountains.. most were experienced railroad crews.. many were probably veterans of the Transcontinental Railroad.” p94

“By mid 1878 as Chinese crews worked at both ends of Wright’s tunnel, a pocket of coal gas was struck.. oil seeped from the walls of the tunnel, collecting in pools on the tunnel floor while gas mixed with air in the tunnel, creating an extremely volatile and dangerous situation.

On February 13, 1879 during a routine burning of the coal gas, some oil caught fire and a sheet of flame roared through the tunnel, badly burning everyone in the tunnel, which acted like a huge cannon, railroad cars and equipment standing outside blown about like toys.” p97

“November 17 1879, twenty-one Chinese and two whites were working at the tunnel face 2,700 feet into the mountain when a small dynamite charge ignited undetected gas. With a roar and shock that shook the mountains from base to summit, a sheet of flame roared out of the tunnel.

Hearing the explosion, 20 Chinese rushed out of their tents and into the tunnel to rescue their comrades. When they were 1,500 feet into the tunnel a 2nd explosion occurred, followed by a sheet of lurid flame which the great mountain belched forth, consuming everything before it.

Of 41 Chinese in the tunnel, 24 were killed outright and the remaining 17 were badly burned. Some of the wounded were taken to Chinatown, San Francisco for treatment, but despite the efforts of Chinese and white physicians, 7 more Chinese died bringing the death toll to 31.” p.99

“In February 1881, a huge mud avalanche swept down a mountain above Felton and buried a camp of Chinese railroad workers. A dozen bodies were eventually recovered but it is not known how many others may have been swept down the rain-swollen San Lorenzo River.

The Chinese never received any public recognition for their enormous contributions to the construction of the South Pacific Coast Railroad; they weren’t mentioned in the railroad dedication speeches.. only reminders at Wrights; 31 Chinese grave markers beside the tracks.” p.101.

“As the Chinese tunneled through the Santa Cruz Mountains the Southern Pacific made its first move to counter the network of narrow-gauge railroads that threatened it’s hegemony. It bought Monterey & Salinas Valley Railroad in 1879; Chinese labor tore up the narrow-gauge tracks..

..and began grading a broad-gauge line..

The Santa Cruz Railroad went under when its San Lorenzo River trestle was knocked down by a flood in February 1881. In a Sheriff’s sale in spring 1881, much of the railroad’s stocked passed to the Southern Pacific.

The Santa Cruz Railroad went under when its San Lorenzo River trestle was knocked down by a flood in February 1881. In a Sheriff’s sale in spring 1881, much of the railroad’s stocked passed to the Southern Pacific.

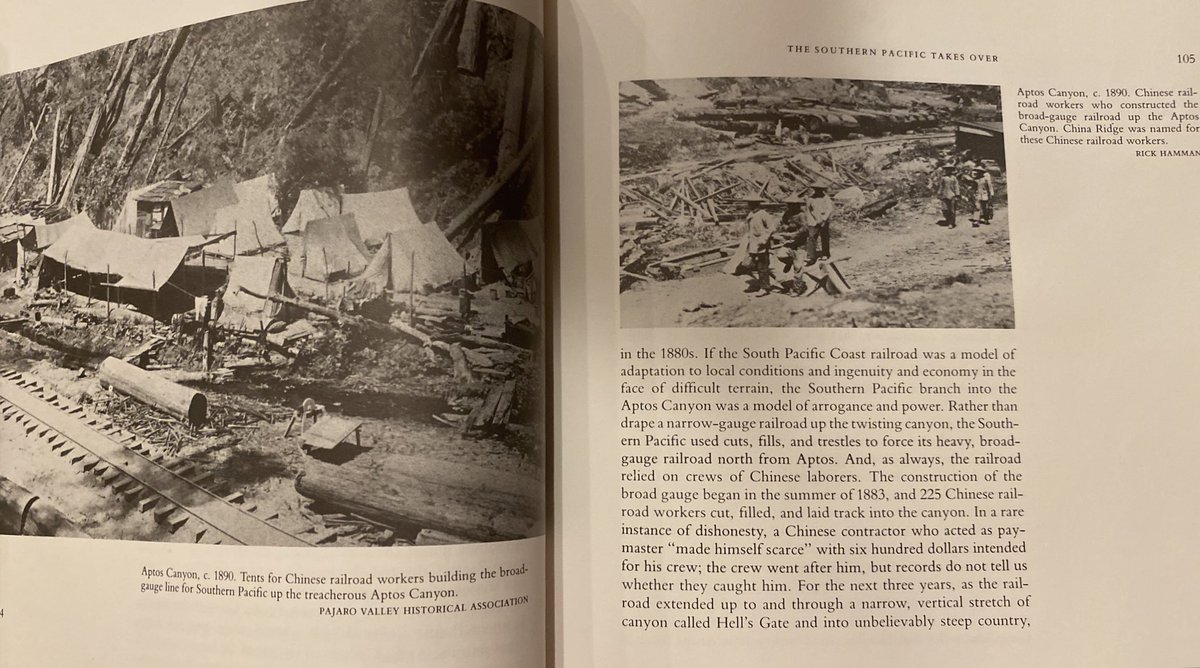

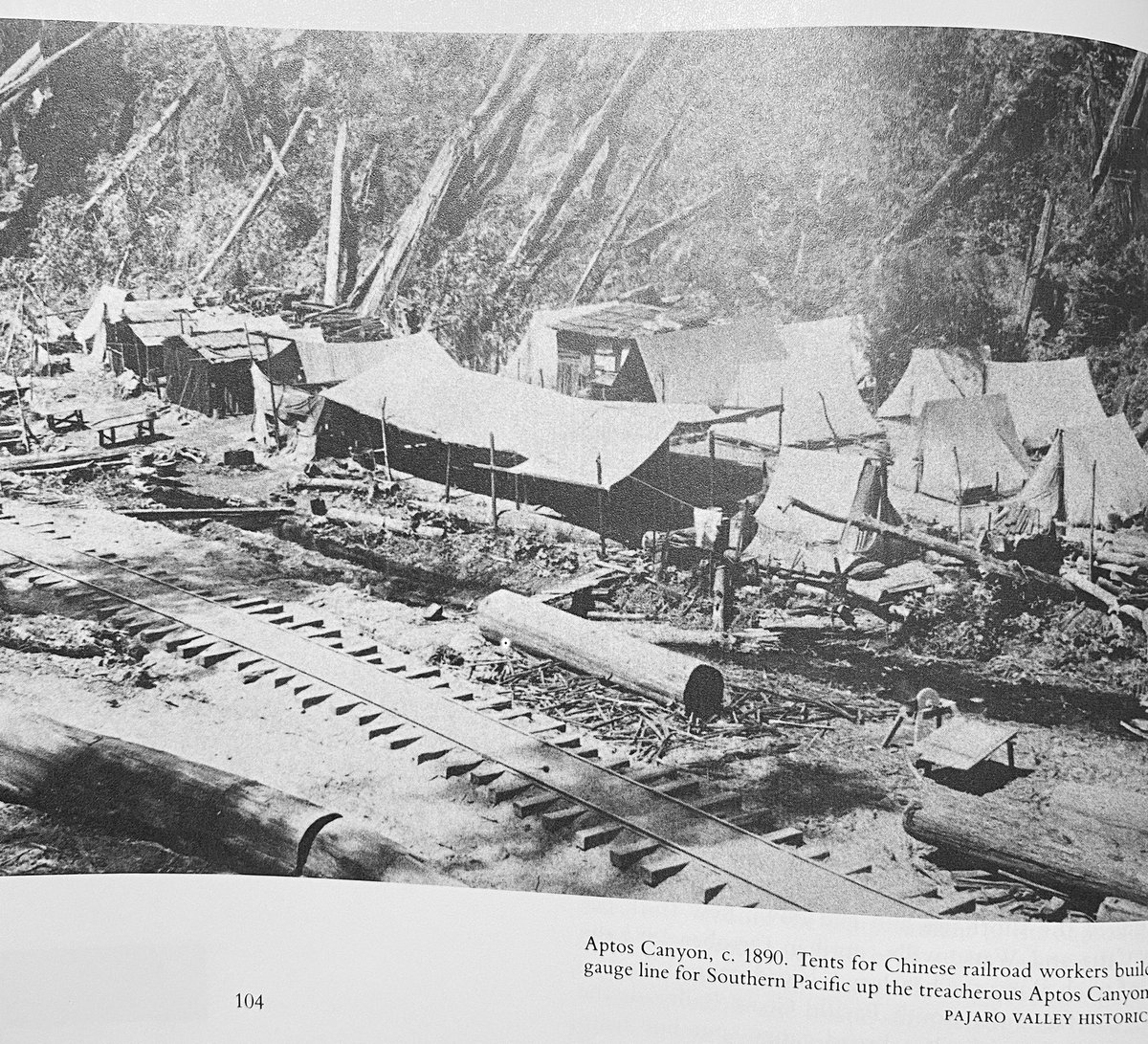

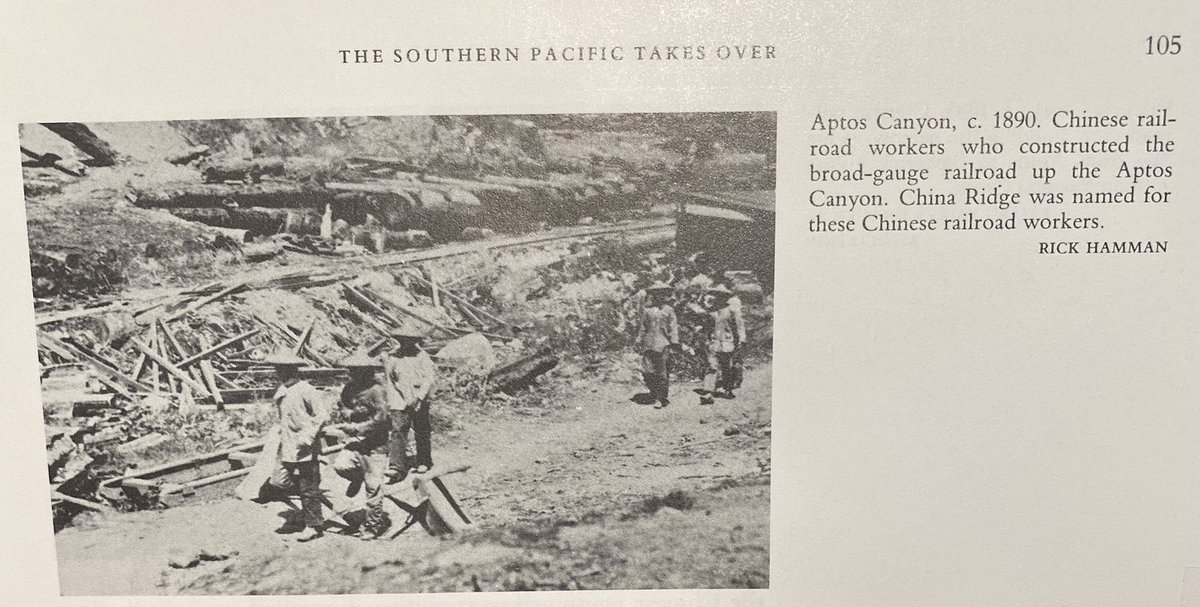

The Southern Pacific Railroad built a broad-gauge spurline from Aptos into the Aptos canyon to tap one of the largest stands of old-growth redwood timber still standing in Santa Cruz County (*today Forest of Nisene Marks). As always, the railroad relied on Chinese labor.” p. 103.

“Southern Pacific’s branch into Aptos Canyon was a model of arrogance & power. Rather than drape a narrow-gauge railroad up the twisting canyon, they used cuts, fills, and trestles to force its heavy broad-gauge railroad up a narrow canyon called Hell’s Gate.” p.105 #ChinaRidge

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter