But let me explain what that was a picture of. In March, Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. It included a provision that allowed some workers who were affected by COVID-19 to take two weeks of emergency sick leave with full pay. (2/11)

When I saw this legislation, I hoped that it would reduce the spread of COVID-19. I knew the literature on paid sick days, and how they stopped the spread of illnesses like the flu. (3/11)

But I was also worried. The law didn’t apply to workers at large employers. So millions of food and retail workers were left out. Workers without the resources to stay home without pay, who interact with customers face-to-face if they come in sick. (4/11) https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/14/opinion/sunday/coronavirus-paid-sick-leave.html

Oddly, the law also carved out healthcare providers and emergency responders . (5/11)

. (5/11)

. (5/11)

. (5/11)

I was also worried because I know how hard it can be to get benefits. It takes work to ensure that people are aware of the rights they have and how to access them. Indeed, much was left to be desired with the DOL roll-out of this new benefit. (6/11) https://www.newsweek.com/why-americans-dont-know-about-their-right-paid-sick-leave-opinion-1501532

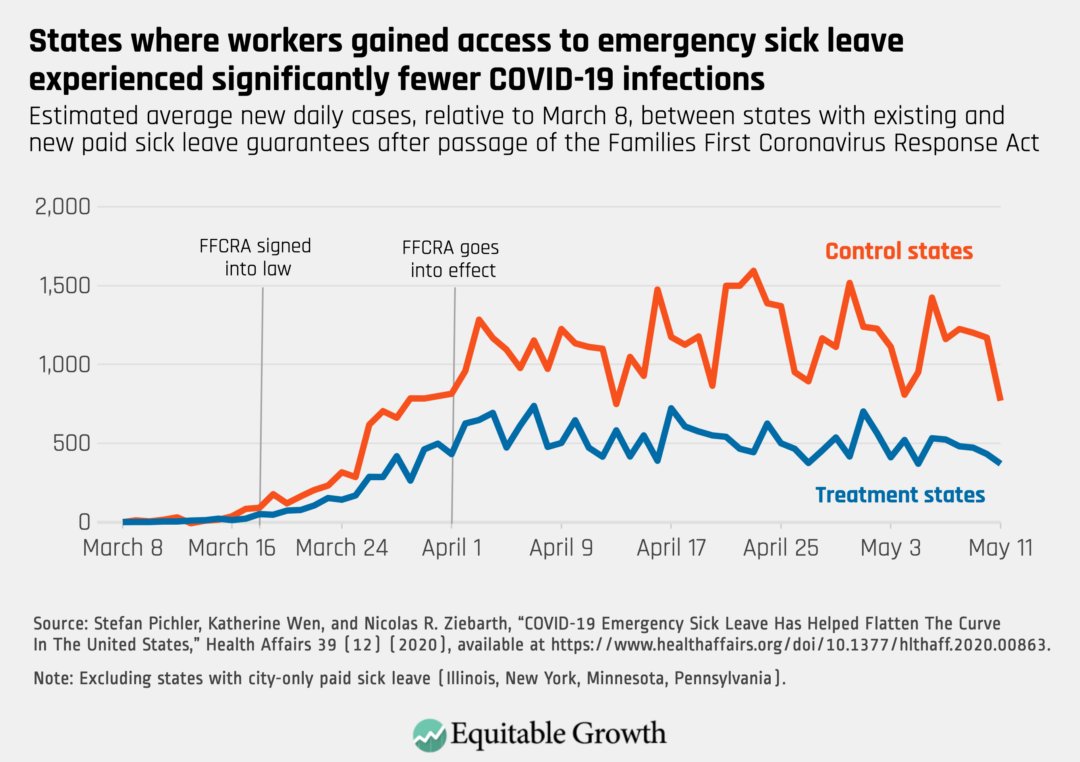

So @NicolasZiebarth, Wen + @StefanPEcon's study made my jaw drop. Comparing the change in reported COVID cases in states that already had paid sick laws to those who didn't, they find that the new law reduced COVID transmission by 400 cases PER DAY. (7/11)

https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00863

https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00863

400 cases per day. 400 cases per day, despite the large numbers of vulnerable workers who were left out. 400 cases per day, despite the lack of a coordinated public awareness campaign. 400 cases per day, despite the fear of employer retaliation in a slack labor market. (8/11)

So of course that made me wonder: how many cases could be prevented, and how many lives could be saved, with a better paid sick leave guarantee?

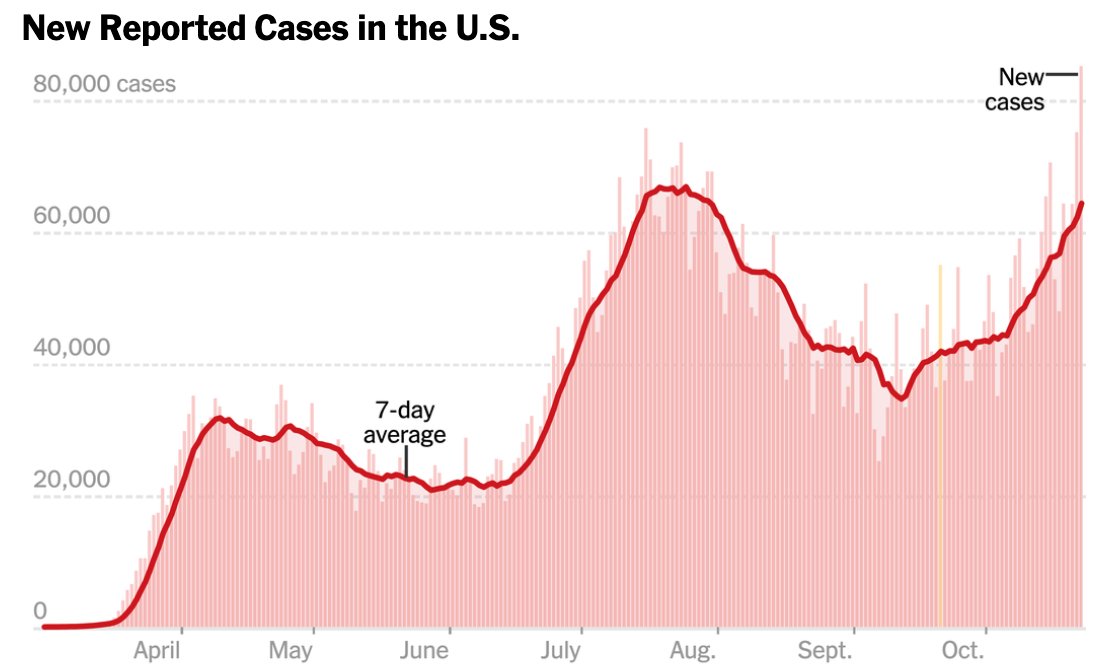

A question that is all the more pressing as the number of new COVID cases hits an-all time high. (9/11)

(chart from @nytimes)

A question that is all the more pressing as the number of new COVID cases hits an-all time high. (9/11)

(chart from @nytimes)

If you are wondering, too, take a look at this new @equitablegrowth fact sheet that provides more details about the study + new policy directions to consider. Thanks @Sam_C_Abbott for making the fact sheet happen. (10/11) https://equitablegrowth.org/factsheet-new-study-shows-that-emergency-paid-sick-leave-reduced-covid-19-infections-in-the-united-states/

And finally, I highly recommend this article by the talented @EmilyRPeck for an accessible and accurate summary of the study its implications. (11/11) https://www.huffpost.com/entry/paid-sick-leave-significantly-reduces-covid-19-cases-study-finds_n_5f8a1d27c5b6dc2d17f6d771

I’m thrilled by the reception this thread has received and have three follow-up points to make… (12/11)

First, I was imprecise when talking about the 400 COVID cases per day that were prevented—that should be 400 cases per day per state without a sick leave guarantee. (13/11)

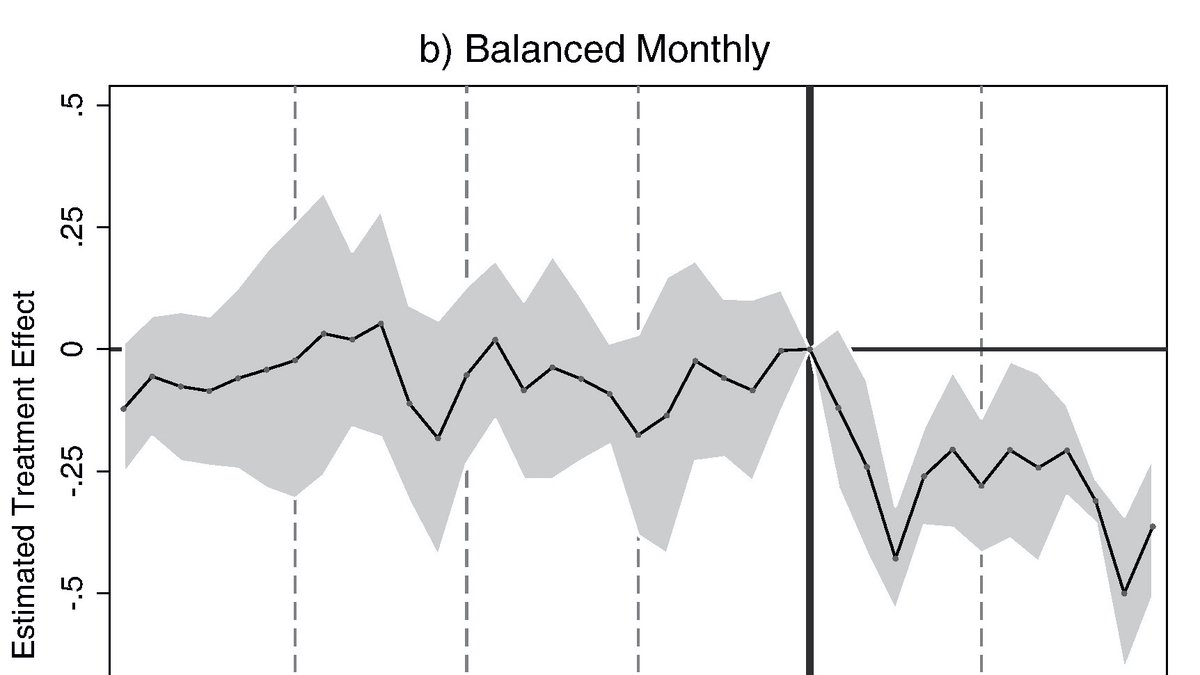

Second, no one study is definitive. Because there is a limited time period in which COVID test data were collected prior to FFCRA passage, and it's uncertain when people began responding to the law, it is tricky to ensure that the parallel trends assumption is satisfied. (14/11)

That being said, the authors have a thoughtful discussion of the issue in the paper, and their findings are in line with other work that shows a behavioral response to FFCRA (see https://www.nber.org/papers/w27138 by #EGgrantee @JCMecon and co-authors:). (15/11)

Despite this limitation, the @HealthAffairs study presents the best available evidence on the paid sick leave guarantee in FFCRA. I look forward to seeing the work of other scholars on this topic + how the important evidence presented here enters the policy discussion. (16/11)

Which brings me to point three: the FFCRA sick leave provision ends on 12/31 unless Congress acts, but the pandemic is likely to rage on. (17/11)

The expiration of the leave would provide a new natural experiment that we could use to study its efficacy, but the evidence in the @Health_Affairs paper suggests that such an experiment would be quite costly. (fin)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter