Though openly opposed to sexual violence against women at a literal level, Claremont’s X-Men does frequently participate in a long-standing comics trope of commercializing implied sexual violence against women. 1/8 #xmen

This trope is entrenched in comics history, tracing its origins back to the first ever superhero comic in Action Comics #1 where Butch Matson is rejected by Lois Lane, so he abducts her (with a clear trajectory toward sexual assault). 2/8

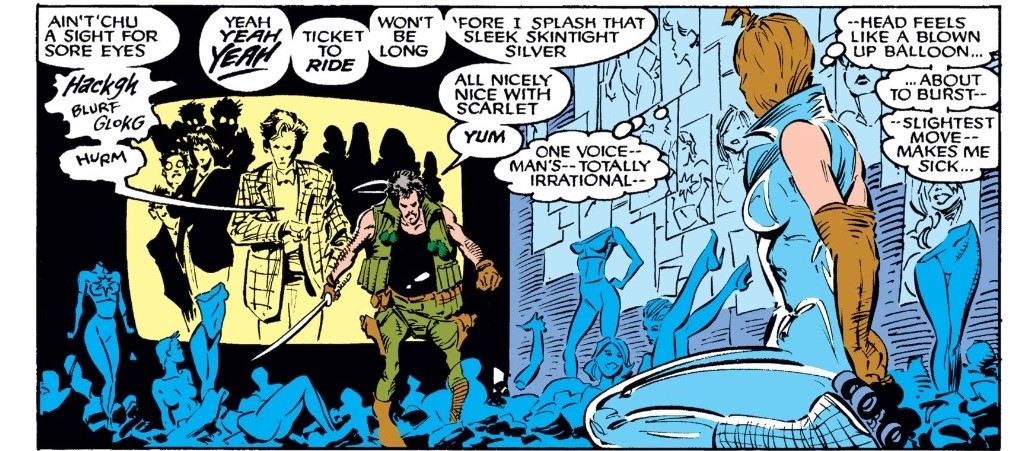

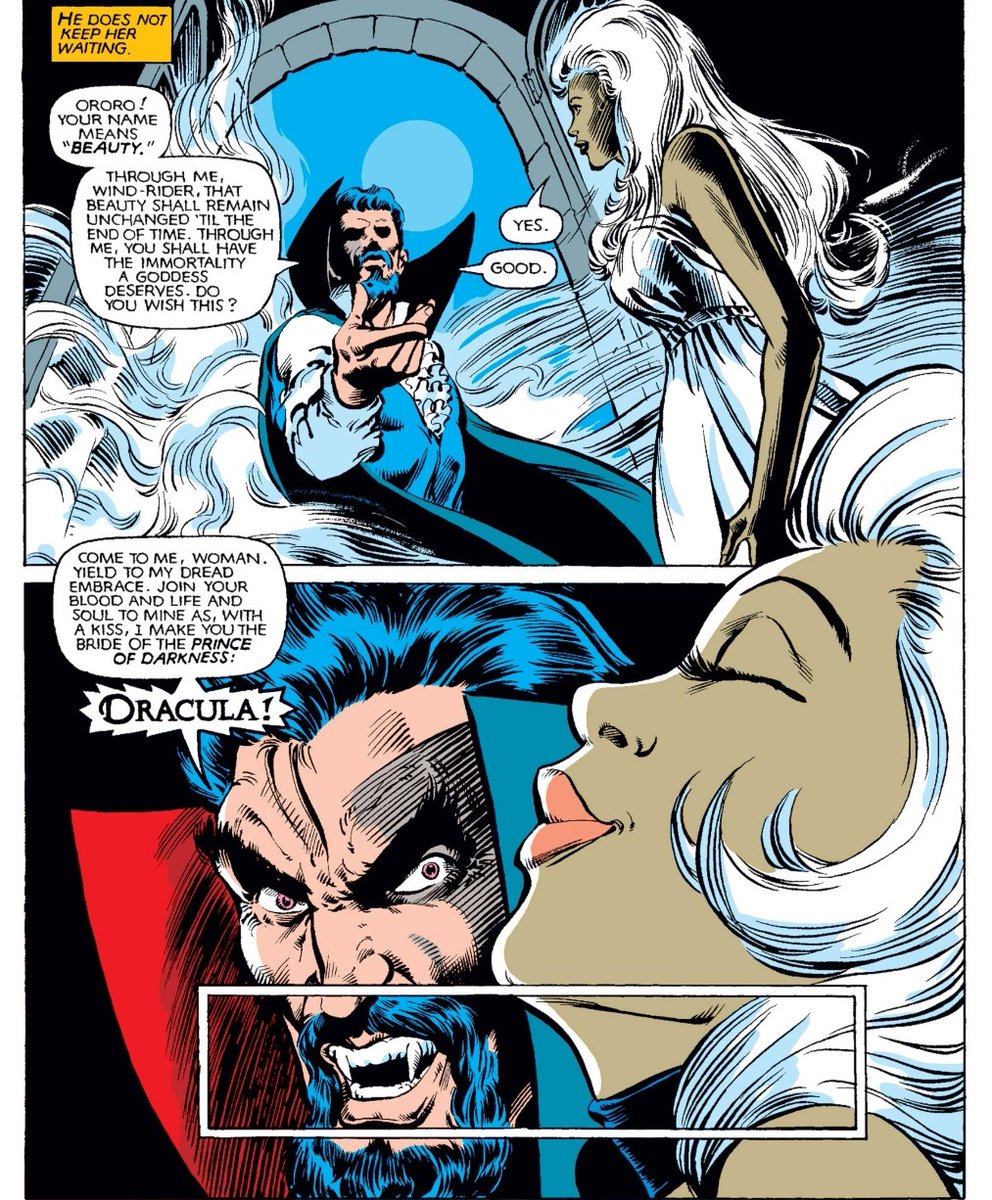

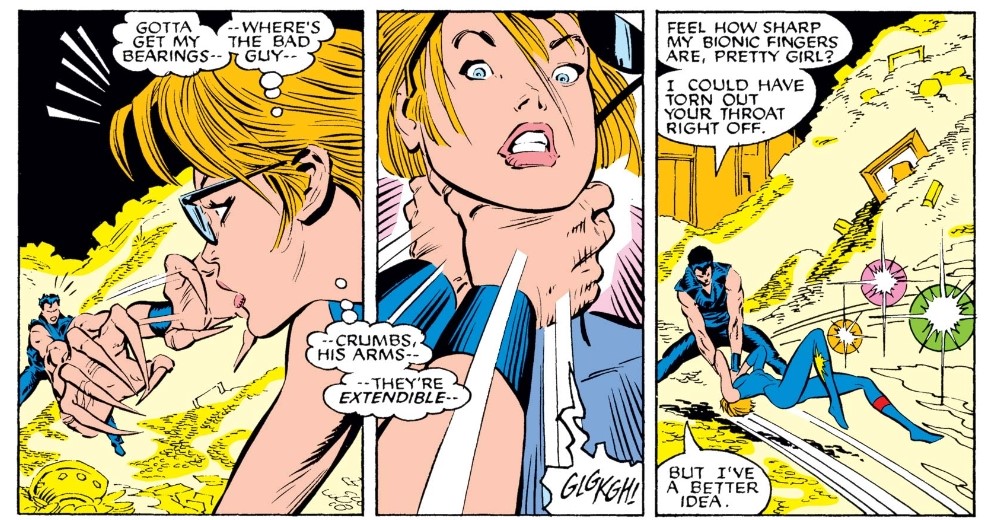

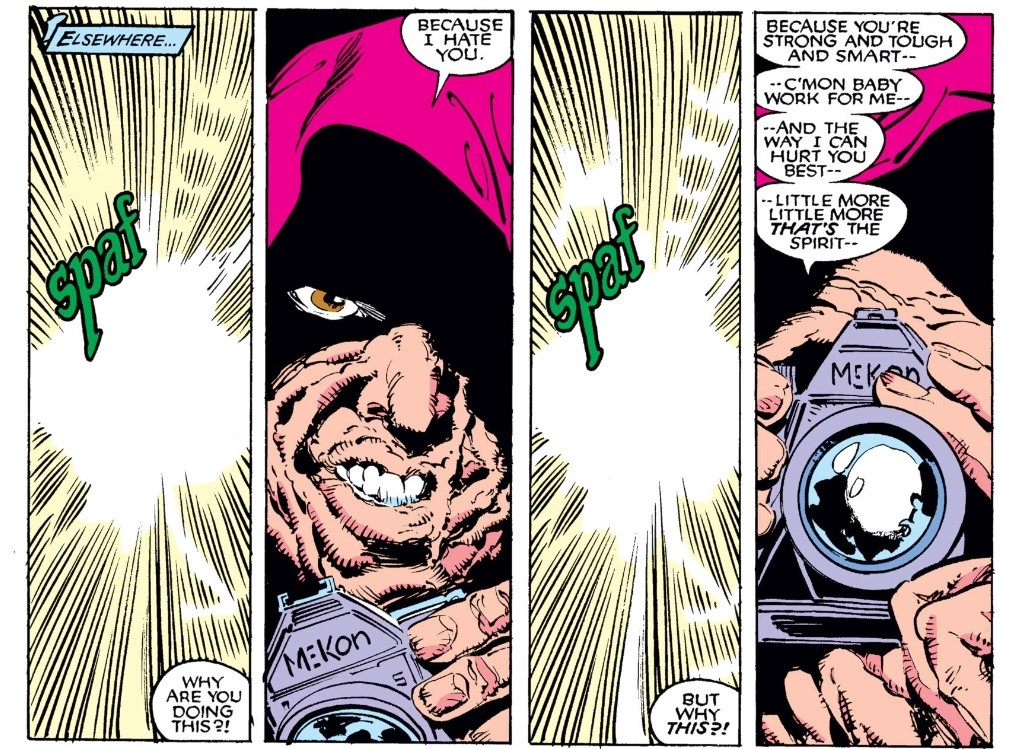

Again and again in comics, women are taken, stripped of their power by a male figure who lusts after them and who (as a villain) would take the next step to sexual assault were it not for the intervention of the hero who saves the damsel in distress. 3/8

But the trajectory was there, and key elements of violent and misogynistic sexual fantasy were there also. That those actions were villain-coded can actually make them more dubious by appeasing the guilt of the audience consuming these fantasies. 4/8

X-Men does this a lot: from Loki/Dracula/Doom making Storm their consort (often undressing and redressing her off-panel in the process) to Caliban’s attempted marriage to Kitty (including a dressing/redressing) to Moonstar being subdued via forced orgasm. 5/8

In this sense, Claremont’s work remains remarkable from the perspective of 2nd wave feminism (which focuses on cultural equality) but less so in terms of 3rd wave feminism (which takes up the dissemination of implied threats of sexual violence against women more directly). 6/8

More broadly, the trope of women being abducted by desirous villains is omnipresent in our culture, extending quite clearly into even G-rated family entertainment (such as the Mario Brothers video game franchise) largely unchallenged. 7/8

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter