New paper alert

New paper alert

Very excited about new paper with @SayWhatYouFound title:

Improving data access democratizes and diversifies science

forthcoming in @PNASNews

with @esther_shears & @MathijsdeVaan ( @BerkeleyHaas)

link: https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2020/09/02/2001682117

Thread

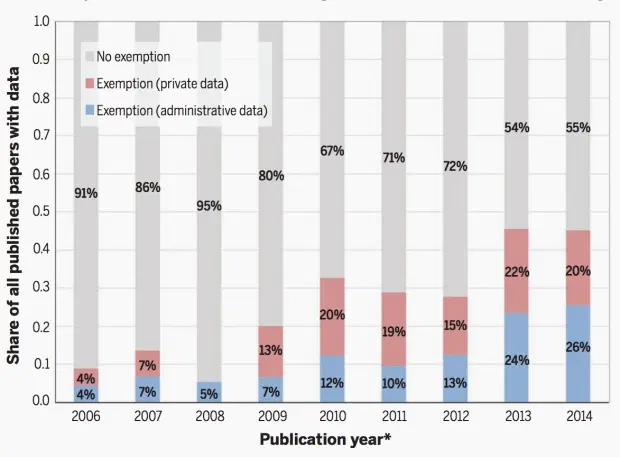

Most modern science relies on empirical data & yet access to many types of data is often restricted or costly (think IRS data in econ, see below https://qz.com/297790/the-remarkable-rise-of-big-data-economics/)

how do costs of data affect who participates in science and what science gets produced?

how do costs of data affect who participates in science and what science gets produced?

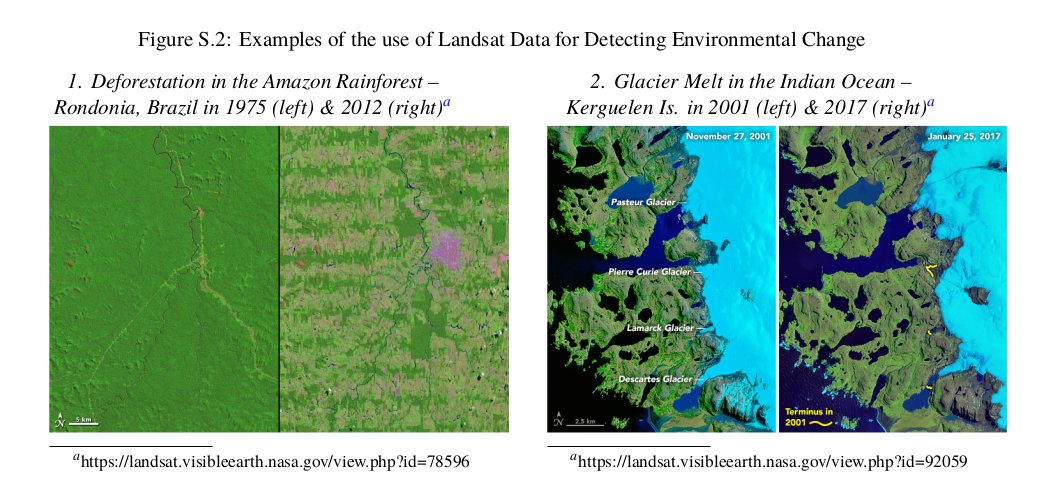

To tackle this question we study data from @NASA_Landsat (one of the most important source of satellite imagery) and its use in earth and environmental science (for e.g. to study glacial melt or deforestation).

Landsat data was commercially available at high cost in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but was de-privatized and moved into the public sector in the mid 1990s. Costs came down and data sharing was also allowed.

How did this change affect academic science?

How did this change affect academic science?

To identify the causal effect of Landsat data we exploit the fact that Landsat data was not available for all places equally (due to cloud coverage for e.g.) -- some places had high coverage and were more affected by cost changes, while other places can act as controls

We also exploit a unique dataset of 24,000+ Landsat pubs that we match using ML/NLP techniques to 3000+ "study locations" as well as to 34,000+ authors.

With these data & a plausible ID strategy, we can map out how data access and sharing costs shape science.

With these data & a plausible ID strategy, we can map out how data access and sharing costs shape science.

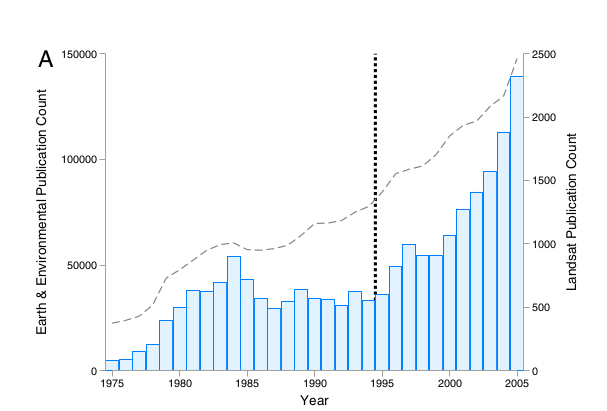

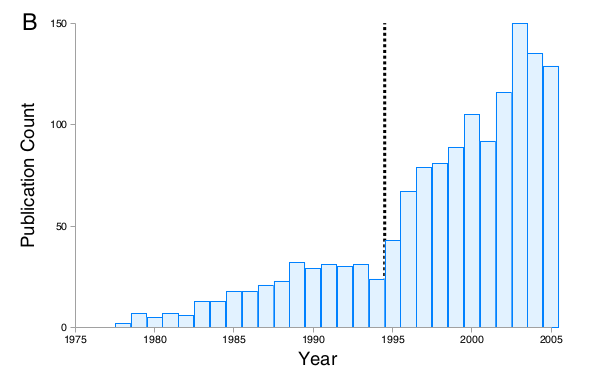

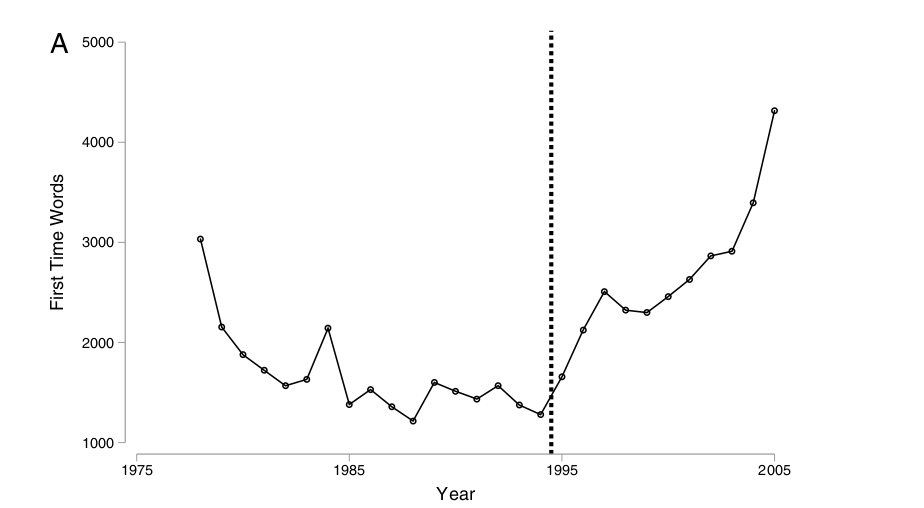

We first document that lower costs were good for science overall. 3x more publications (left) & 6x more pubs with 100+ cites (right).

This result is robust to a number of alternate specifications, including comparing with non-Landsat controls.

This result is robust to a number of alternate specifications, including comparing with non-Landsat controls.

Who are these new pubs coming from? Are those who published before now publishing more or is it from new people?

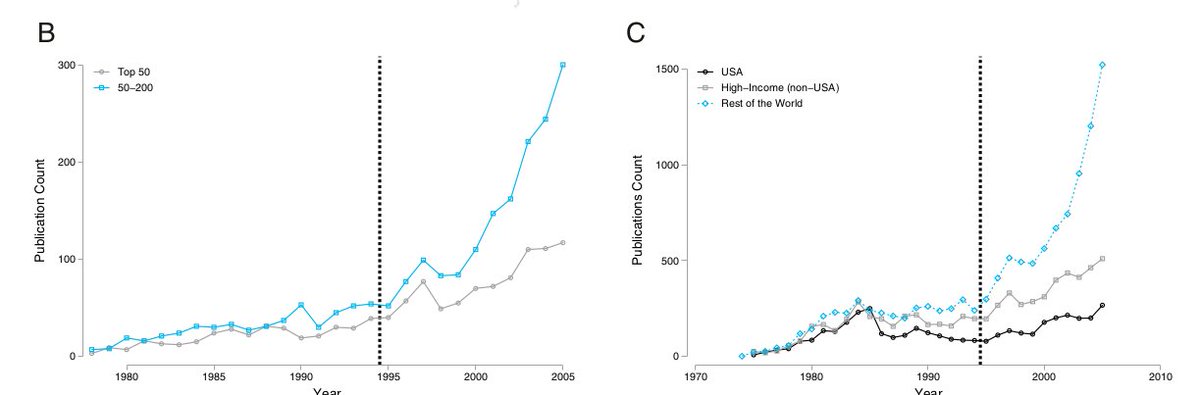

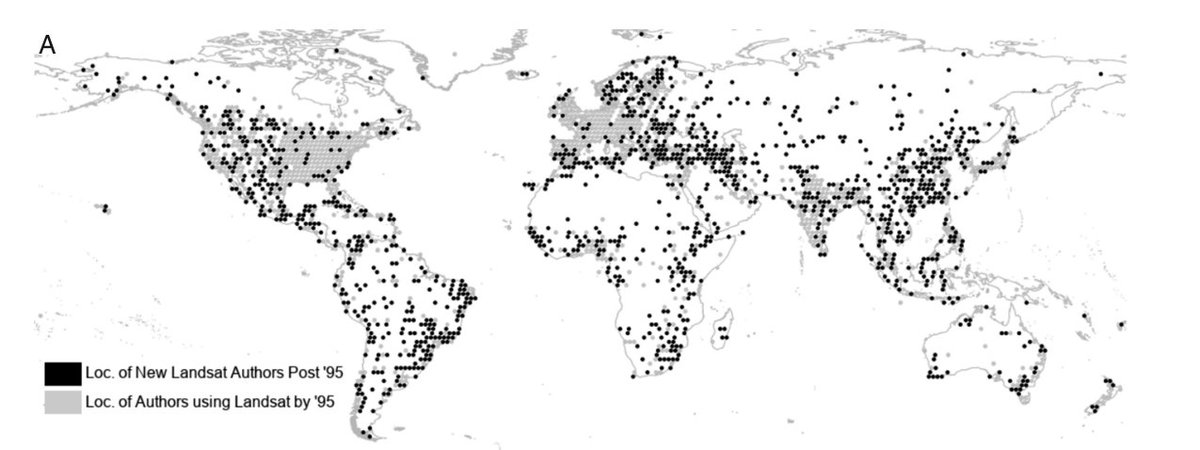

We document that the increase is much stronger among authors in non Top-50 academic institutions and from low and middle-income countries.

We document that the increase is much stronger among authors in non Top-50 academic institutions and from low and middle-income countries.

A striking way to see this is to compare new author locations (black dots) with pre-existing author locations (grey dots). The black dots are much more in south america, eastern europe, the middle east and africa

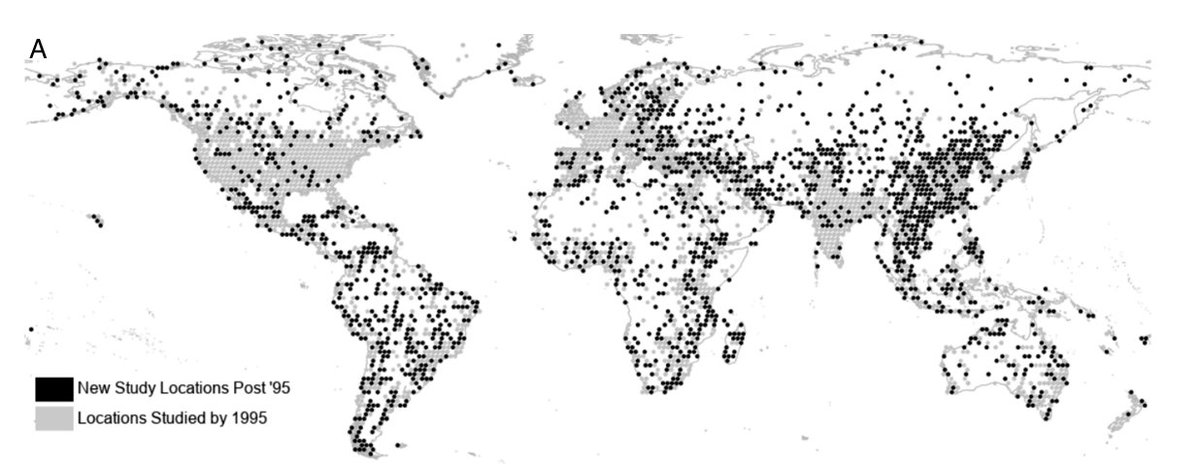

What are these new authors studying? As it turns out -- a more diverse set of regions & a more diverse set of topics!

For e.g., African authors start studying African wildlife using newly accessible data, a topic that was previously ignored even though the data were available.

For e.g., African authors start studying African wildlife using newly accessible data, a topic that was previously ignored even though the data were available.

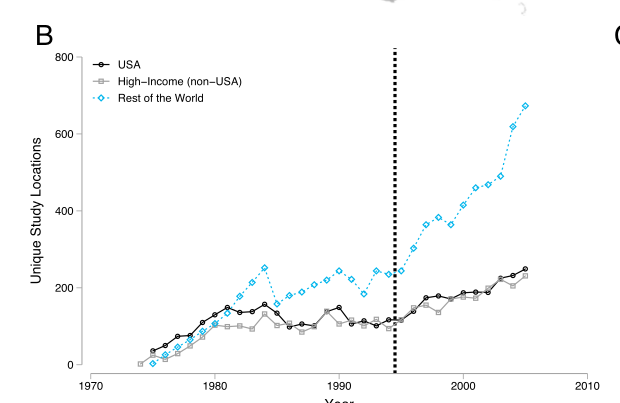

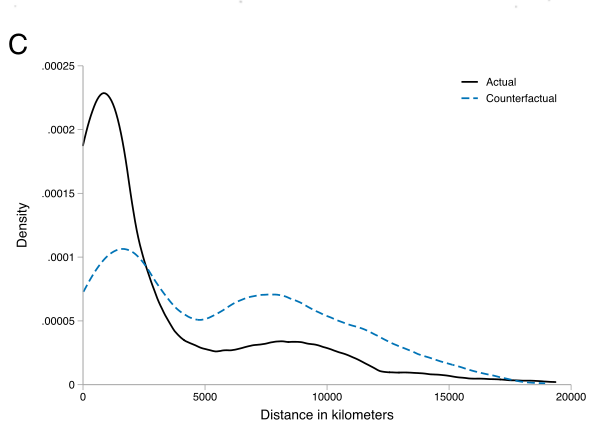

Look at how the number of places that are now researched for the first time (black) expands dramatically when new authors enter the field.

What's more -- these new authors are not only diversifying science in geographic space, but also in topical space. They introduce more novel topics and introduce "first time" concepts to the literature.

The upshot is that data access policy shapes science and scientific diversity in important ways.

By excluding those who cannot afford data, we are losing high impact research AND neglecting research topics that are disproportionately important for the disenfranchised

By excluding those who cannot afford data, we are losing high impact research AND neglecting research topics that are disproportionately important for the disenfranchised

I worry than the turn to expensive, proprietary "big data" in the social sciences will make us less diverse, but I'm also excited about modern initiatives like @placekeyio which provide open access to high-quality data for all to work with.

Thanks to @MathijsdeVaan and @esther_shears for fun time writing this paper. Our data and code can be accessed at: https://osf.io/mw34x/

Thanks for reading this far! My inbox is open for any feedback.

/FIN.

Thanks for reading this far! My inbox is open for any feedback.

/FIN.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter