How do we go in the space of a few years, a few months rather, from 'the future is urban' to 'the death of the city'? A thread on what I think we're getting right and wrong about the current moment

For the last 20 years, thinking about planning and cities has been dominated by 'The Urban Agenda' (see https://www.lse.ac.uk/cities/publications/books-and-chapters/The-Quito-Papers-and-the-New-Urban-Agenda ) but in the aftermath of Covid there have been foreboding pronouncements about the end of the city like the article above https://www.politico.eu/article/the-death-of-the-city-coronavirus-towns-cities-retail-transport-pollution-economic-crisis/

The tipping point for 'the urban age' was a statistical milestone, sometime over the past decade half of the world's population was living in cities. The dominant discourse in professional and academic circles was that dense cities are the future and we should plan accordingly.

Cities were upheld as better environmentally, they use less land and limit sprawl, better culturally and socially, they allow for interaction and the arts, even better politically as the fear of the insular suburban mentality became a theme, whereas cities are more diverse

How do we then explain this sudden shift? Has the virus completely destroyed all the reasons why we love and want to live in cities? I think there are two things at play here: the dominant urban thinking was flawed and the current pessimism is premature and shortsighted

Let me start with the first, in the West in particular a formula emerged over the past 20 years: denser cities are better, suburbs are bad, commuting is better than driving, etc. An idealised image of city life was created that didn't match the reality, but policy was based on it

The idealised image failed to understand the exurban form of Western cities and why they were emerging economically and socially, cities are not their tourist centres and living/working on the periphery isn't anti-urban but part of a new form of urbanity enabled by technology

Meanwhile the pro-density policies had an unintended consequence that is still not fully recognised, as urban flight was reversed and city centres became more desirable they became increasingly exclusive and expensive, pushing poorer communities out to the peripheries.

In parallel there was a severe degradation in the quality of low-income housing within cities, more people crammed together, new 'slum' dwellings emerging, less space, so it was either move further out or accept less. Meanwhile, the affluent had their pick of luxury apartments.

Those who had championed urban policies that partially led to this situation were slow to recognise the impact these policies were having, it was simple: as you make city centres more desirable without social policies to protect low incomes residents, the affluent will take over

It was a fantasy sold on appealing images of healthy people sipping coffee in city squares, but its obsession with a narrow definition of urban life within historic centres with elegantly designed new apartment blocks ignored what real urban life was like to the majority.

So the first problem is that we have a prevailing urban narrative that doesn't quite understand the complexity and scale of the modern metropolises. They are large networks of urban, suburban and exurban forms that are intensely connected, not postcard cities, a new urbanism.

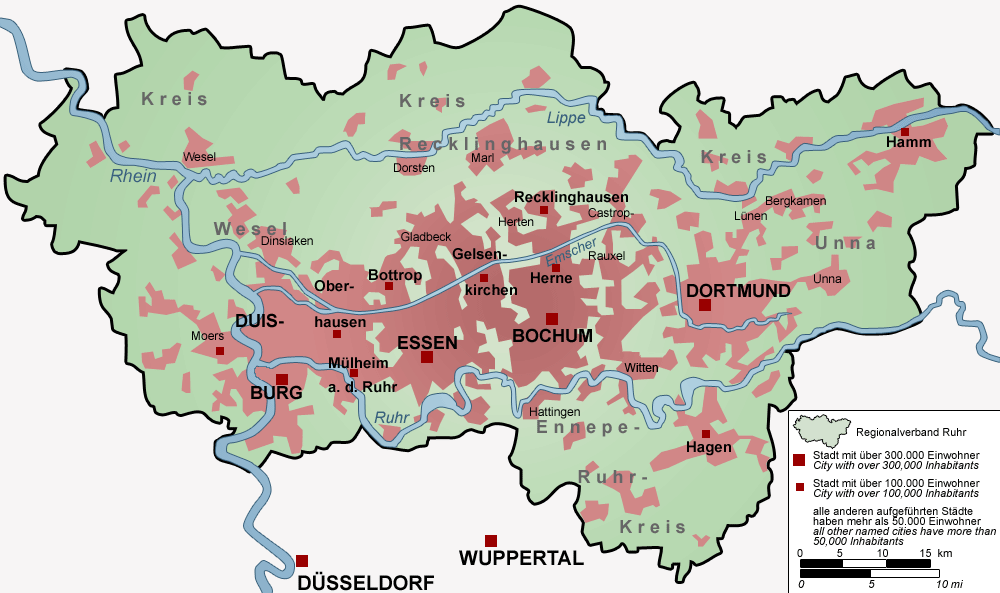

Take the Ruhrgebiet for example, it's arguably the largest urban area in Germany with somewhere between 5 and 10 million people depending on how you define the boundary, but no single city within is larger than 600,000 people.

It's possible to live anywhere within the area and commute to another part. You might go entire days without going to a traditional 'city', like Dortmund or Essen. Is your life less urban? Certainly not. You have access to culture, social interaction, the whole range of activity

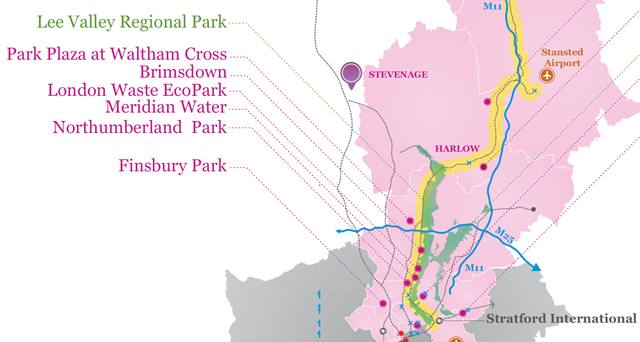

Another form exists in the London/Cambridge corridor. In both contexts there are large green areas within those metropolitan zones with significant economic activity, but the patterns of urban life are not strictly defined by traditional forms of commuting, living, and working.

So the first issue is we failed to understand what cities were becoming. The second, which is emerging with the scepticism towards the fate of cities, is that we don't know what cities are for. Even the keenest advocates of cities seem to be lost for words in the face of Covid

There are some half-hearted attempts to revive 'the narrative' by lumping in Covid and climate change/environmental issues together and arguing cities, in the narrow definition, are still the solution, but they are unconvincing.

Let's admit that we have been through over the past six months has had a massive impact on our worldview. Overnight we all had to absorb the message that other people are a danger and they should be avoided. How we build back society and trust is a challenge.

Rinsing the same old 'urban' thinking won't cut it. Many of its advocates are clearly flummoxed, everything you have argued for is now seen as a problem: close human interaction, density, public transport. And these can't just be waived away with platitudes about the city.

Which takes us to the second issue, the pronouncements about the death of the city. Much of it is based on many people realising they can work from home and thus leading to offices becoming obsolete and hence the end of cities as we know them.

The same thing could be said of the arts, culture, sports, socialisation. The people who are calling on governments to save them are not prepared to go to a theatre or the pub. With both this and the office, this seems to be a particularly Anglo-Saxon issue.

It's legitimate to ask questions about the durability of the current model of the city in light of this, but the mistake is not to take history into account, how cities have transformed themselves when they faced crises, and their resilience and adaptability.

The most recent example is post-industrialisation in the Western context and the impact it had on cities. Cities had to reinvent themselves and did, and while the trends vary in terms of growth/decline of specific cities the intensity of urban activity zones has increased overall

The economic raison d'être of cities is but one factor, an important factor but not the decisive one. The problem is that much of these assessments are made in the heat of the moment and in response to the crisis mode. Most predictions are projecting too far on a narrow basis

So for example I started seeing 'predictions' about future cities with wider pavements, spaced work environments, compartmentalised public transport, etc, all of which think that we are going to redesign cities wholesale to avoid the threat of contagion.

None of this is likely to happen. Cities are notoriously hard to adapt physically and these processes take decades. Nobody knows how long this period will last but we simply don't have the resources to adapt cities permanently to stop contagion, nor should we.

The bigger questions that we will be focusing on in the coming years will be how we deal with the huge economic and cultural impact of this withdrawal from cities. Again, we need to answer the question what cities are for, why do we (some) love cities and what we want from them

And this not just about how we plan these changes. There will be organic development and trends that can fill any vacuum left by the aftermath of the virus. This is equally true of office space as it is of city districts. Adaptability is key and I feel it's being neglected now.

The area I live in in north London for example lost a lot of the original residents as they moved towards the suburbs but today it's a thriving area with a large Turkish community and other migrant groups. Nobody purposefully planned this but it would been in decline otherwise

But let me go an important tangent to address the issue of the workplace and offices. I have been designing offices (mostly) for 25 years, and I have been involved in researching their future, development and adaptation over the last ten years. I don't buy into the pessimism.

We're definitely seeing a pattern to reduce real estate by office occupiers. But this will create opportunities also. Over these years we have realised that the standardised office space isn't ideal and office design has transformed to allow for more diversity of uses/layouts

We also know that different types of activities require different settings. If you wanted to focus on writing a report you could do it better from home, but if you're in a creative meeting then the right office setting might be better, galvanising that spark of interaction

In parallel, there's more emphasis on the work/life balance and flexible working. Think in gender terms and how beneficial this could be for women in particular. So there's an emerging picture of how you can allow for flexible working and redesign your office to be more focused.

On the face of it, you could end up with less space as nobody needs to be there all the time, but the space you have will be more exciting/healthy/flexible etc. The savings on rents could go towards improving work settings at home and even creating off-site hubs.

but in many fields, we will still need that physical space and the physical interaction, we need the creative spark, the pushback, the informal interaction, all of these are valuable. In many cases of homeworking when people assumed things were 'working', they clearly weren't.

Maybe it's a function of how all of this happened quickly and an improvised way, but we're discovering that as work becomes compartmentalised there are fewer informal quality checks, less critical inquiry, and overall less coordinated results. Hence the need for the 'real'.

But an important factor that gets missed here is the nature of office work isn't just a product of the design, there have been many damaging trends over recent decades, more transient work, less job security, freelancing, all of which break the bonds that form among workers.

In many respects this helps why so many people think of office work as unsatisfying. The conditions were created to weaken the ability of workers to create connections, solidarity and meaning through their work. That remains a struggle in any setting.

Equally, for every dazzling corporate office with bells and whistles there are many box offices with tiny standardised desks and mostly no daylight. I can't blame anyone for preferring to work from home instead of those conditions. But again this is a bigger issue than design

So the trends that we are looking at, and a lot of this will be down to workers formulating clear demands and having a say in the outcome, is demanding more flexibility and better space. The question remains what will happen to the empty office space?

There will be several dynamics at play. Lower rents might mean more companies can afford to move into more central locations. Small industry and crafts might find a home in cities. Then there's adaptability, do we look at converting offices into housing? Into schools?

There's something terrible about London now, because of the pressure on space for office and residential there's hardly any space for anything else. Few swimming pools, few bowling alleys, a general squeeze on amenity. Will freeing up office and retail space create more?

As I say, many of these trends will happen organically but we need to plan for resilience and adaptability to get out of this and get positive outcomes out of it. The right public investment and right choices can achieve that, but this requirements engagement not withdrawal.

But above all, we need to answer the question what cities are for. The pessimistic headlines are focusing shortsightedly on narrow and immediate concerns and can't see beyond them. Doom sells. But we have great lessons from the past on the adaptability and resilience of cities

So let me close with a positive message. Our recent proclaimed fondness of cities was superficial and that's why it doesn't have answers now. We need to appreciate that cities are great places for coming together and accept that change is part of their nature, let's embrace it.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter