1/ OK, so I just carved out some time to really watch The Video attentively. And I think it’s great, an excellent account of @philewell’s work. Really draws together a lot of important ideas.

2/ And though the opening schtick is a tad reductive, it gets better & better as it goes on. It's an awesome model of longform video that makes some potentially arcane material just as legible as the more obvious aspects of this issue. A great achievement, @its_adamneely!

3/ If you watched very carefully, you might notice that I’m cited in it briefly. I was actually going to re-up that article of mine in response to something I recently saw floating around—but now it turns out there are two reasons to do so now.

4/ This was an article I wrote about the tendencies of “thinkpiece music theory” in outlets like Slate, Vox, etc. Public facing music theory, but written by journalists or guest contributors rather than theorists. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:25671/

5/ While I try to put a positive spin on things by pointing out that there is actually huge demand for content about music theory, and that more theorists ought to occupy themselves with providing it - there are some troubling things I identified in this genre.

6/ I’ll preface this by saying I have no interest in being a gatekeeper - I love to see anyone trying their hand at explaining theoretical concepts or analyzing songs, and there are plenty of awesome creators and writers outside of academic music theory.

7/ Anyway, as this paper argues, it’s clear to me that there are at least three common pitfalls that music theory journalism often falls into:

8/ 1. While grounded in actual facts about music, those facts are deployed vaguely, incompletely, or incorrectly. They’re often taken too literally, or perhaps distorted by the game of telephone that seems to happen between the author and whomever they consult with about music

9/ Thinkpiece theory is often grounded in ideas that have filter outwards from academia: either to students, or to popular culture/urban legend more broadly. That is to say, they are grounded in real academic ideas, but often dated or exaggerated versions those concepts.

10/ In that way, thinkpiece analyses often re-enact music theory’s historical debates. From another angle—they sometimes reflect the worst aspects of the discipline: academic music’s worst impulses, as filtered through someone who often knows just enough to be dangerous.

11/ 2. Thinkpiece analyses are *filled* with appeals to authority. This authority may be a journalistic “source” of some kind, often a friend or acquaintance. It might be a scholar. It might be an old historical theorist, or a scholar in another field.

12/ At the top of this rung is Science, with a capital S but no specificity, because we all know that if you call it science, it’s the ultimate authority. Doesn’t matter if it’s good science or bad. Second to that is music theory itself, naturally, as an amorphous master concept.

13/ 3. Thinkpiece music theory is made to be passed around. Digital scholars call this “churnalism.” Not only are popular articles (or YouTube videos, for that matter) meant to be retweeted or otherwise shared; they are also fodder for other publications.

14/ One outlet publishes the article, and a dozen others write “stories” about the article. They might block quote it or give a few choice excerpts, but they basically exist to grab some traffic based on the headline, and then link to the real thing. Then the blogs start up, etc.

15/ So, the passage quoted by @its_adamneely is one of the case studies I quote, in my attempt to problematize the whole framing “using music theory” in a series of Slate articles, some of which are analyzing Katy Perry and Lady Gaga.

16/ I think the framing of music theory as a secret decoder ring for musical insight, an objective lens that will grant you truth or evaluate the quality of a piece of music, is *very* problematic, no matter who is carrying it out: academic, journalist, person on the street.

17/ As I say all the time to my students, “There is no such thing as music theory. There are many theories, about many musics.” [I think I owe that quote to @krisshaffer].

18/ Or, as my PhD advisor Suzie Clark says, “Music theory is something that people made up, in order to talk about music…which people also made up.”

19/ And while I stopped short of describing this as racist when I wrote that paper two and a half years ago, I do call out the framing of the “excellence and supremacy of music theory” as problematic, and critique the specific language used in the Gaga analysis...

20/ ...which attempts to re-inscribe the division between the mind and the body, in order to denigrate the latter: a framing I got from Susan McClary and Suzanne Cusick, et al. I’m proud to have my article cited in this exemplary piece of public music theory.

21/ OK, onto the other topic: So, a few weeks ago these “solfeggio” videos came to my attention. Here's an example [=/= endorsement!]

22/ There are people out there who believe that listening to these frequencies can have healing effects, from—and I quote “liberating guilt and fear” to “restoring spiritual order” and even “transformation and miracles (DNA repair).”

23/ If you Google “solfeggio tones,” you find a lot of websites that want to teach you about them. Sometimes these sites just want your clicks. Sometimes they’re wellness websites talking about solfeggio as only one branch of mystical quackery alongside many others.

24/ [And, I’ll note, their messy distillation of concepts from early modern western music theory mirrors the appropriation of various ideas from different eastern traditions in the service of ‘wellness.’]

25/ Sometimes they want to sell you things: mp3s, or even accoutrements like Tibetan singing bowls tuned to specific frequencies. They reflect at least two of the characteristics I identified in thinkpiece music theory:

26/ 1. They’ve obviously been passed around and filtered multiple times. The internet is a giant game of telephone, or of copying and pasting. (Churnalism). So most solfeggio websites use the *same* language to describe their origins and which health benefit comes from which tone

27/ 2. They’re grounded in real music-theoretical or scientific ideas (musical tones come from vibrations at different speed; Guido of Arrezo invented solfeggio syllables in the 11th century for his choir, based on the existing hymn “Ut queant laxis.”)

28/ These principles are always treated as profound, and described as lost or arcane knowledge that modern musicians and modern science have both lost sight of.

29/ And of course there are problems, both of the mystical woo-woo variety, AND in the getting basic facts of music wrong. Like, I haven’t done the digging to figure out it the frequencies given actually fit within a standard system of intonation or if they’re just random...

30/ or numerologically derived sequences (Numerology is big, as is Da Vinci Code-style decoding. But even from comparing them to their closest equally tempered analogues, they aren’t actually expressing Ut-Re-Mi etc. They’re mostly an assemblage of half steps and thirds.

31/ They aren’t a Guidonian hexachord unless your preferred version goes G, G#, C, Eb, F#, G#. Good luck solmizing a hymn with those notes. Or a plum for that matter. https://twitter.com/oharatheorem/status/1170164256794402817

32/ I’ll round all of this out by saying there’s a not insignificant helping of outright mysticism in the western music theoretical tradition. Music theory has its own origin myth in the tale of Pythagoras and the hammers.

33/ The story may be apocryphal; it gets the details of acoustics wrong (solid objects like bells—or hammers—behave differently than strings and express different tuning ratios); it is subject to accretion, in the form of new details like the discordant and discarded fifth hammer

34/ [The fifth hammer was added to the tale later, by Boethius, for an extra moral edge.] And the theoretical canon includes people like Robert Fludd, whose celestial monochord looks like something straight out of Monty Python. https://www.google.com/search?q=fludd+celestial+monochord&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjynPuc0drrAhWKknIEHQFgALcQ_AUoAXoECAwQAw&biw=1280&bih=666#imgrc=M8xYoYjIF9z1eM

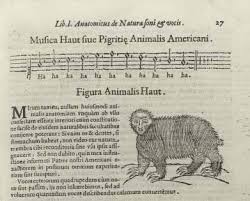

35/ and apocryphal origin stories like Athanasius Kircher’s tale of the sloths in the new world, who allegedly sang in hexachords.

36/ That these untamed beasts in that “untamed” [biiiiig scare quotes there] new world sang in the very same arrangement of tones that Guido used was meant to be evidence that the major scale was natural and inevitable.

37/ It’s worth noting that this kind of spurious origin or numerological justification pops up not only in the ‘quirk’ histories of music theory’s dead ends, but in the most mainstream of canonical theorists: Zarlino (the senario), Riemann (undertones), Schenker (take your pick)

38/ The place of numerology and other spurious modes of argument has been well documented by Suzie Clark [see “Schenker’s Mysterious Five” and her very non-garbage-firey contribution to the garbage fire issue of the Journal of Schenkerian Studies.]

39/ And it’s not just Schenker: any attempted scientific or rational justification of western musical systems will hit a snag, somewhere. No tuning system is perfect. No determination of which intervals are acoustically consonant, or how much of the overtone series...

40/ should be admitted to justify the major [and minor] triad, has a non-arbitrary cutoff. As I say in the “Thinkpieces” paper, a lot of music theory “journalism” is just reflecting our own intellectual histories back at us in newly unexamined ways.

41/ And the takeaway from all this might be that we aren’t as “beyond” these modes of thinking as we like to think we are. Sure, maybe we no longer think that harmonic consonances can describe the orbits of planets...

42/ ...but it’s become clear in the work of @philewell and many, many others that alongside the obviously toxic aspects of our profession, there are many dusty corners and bad habits of thought remaining to be scrutinized and rooted out as well.

43/ FIN for now. Further reading to come!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter