Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, Chelsea have been spending big in this summer’s transfer window with their estimated outlay well over £200m. This thread will look at the financial implications and explain how #CFC will still be able to meet the Financial Fair Play (FFP) targets.

We should note that the amounts used for transfer fees and wages are not officially published, so the numbers used in this analysis might not be 100% correct, but they should be sufficiently accurate to illustrate the financial impact.

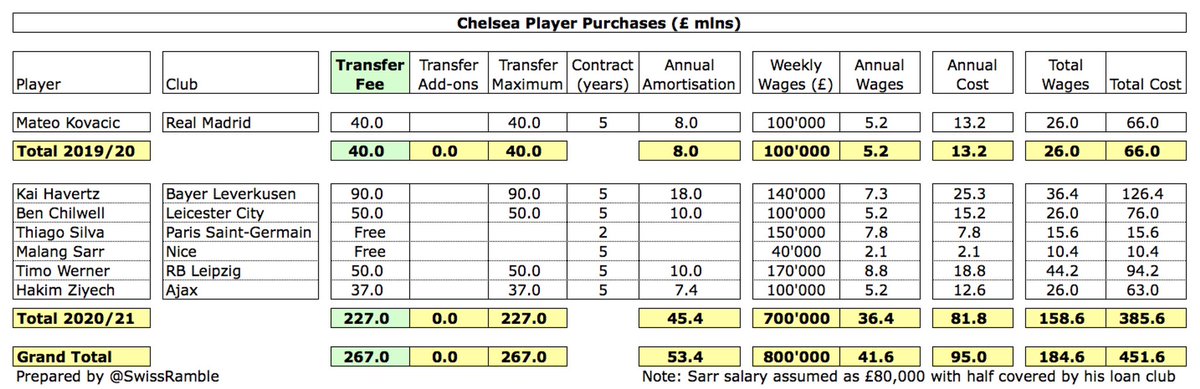

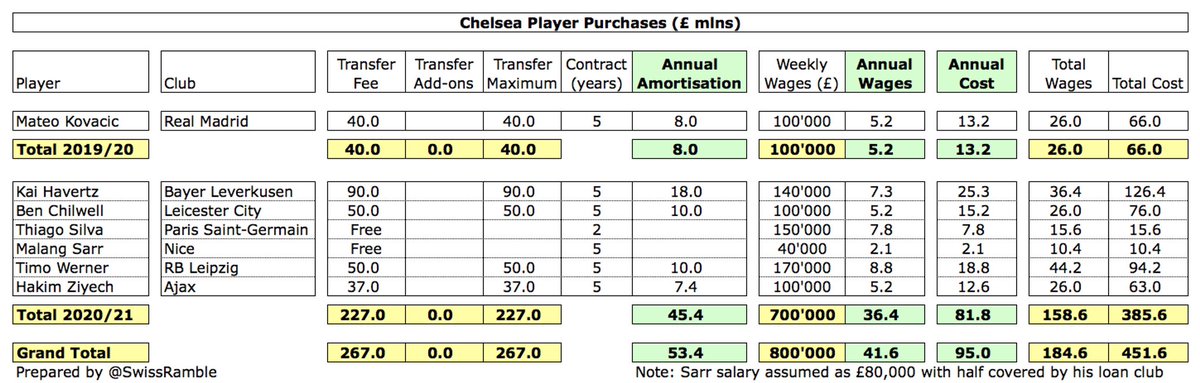

Assuming that #CFC acquire Kai Havertz £90m, their spend will be around £227m, including Timo Werner £50m, Ben Chilwell £50m and Hakim Ziyech £37m. They have also added Thiago Silva and Malang Sarr on free transfers. Prior season only saw purchase of Mateo Kovacic £40m.

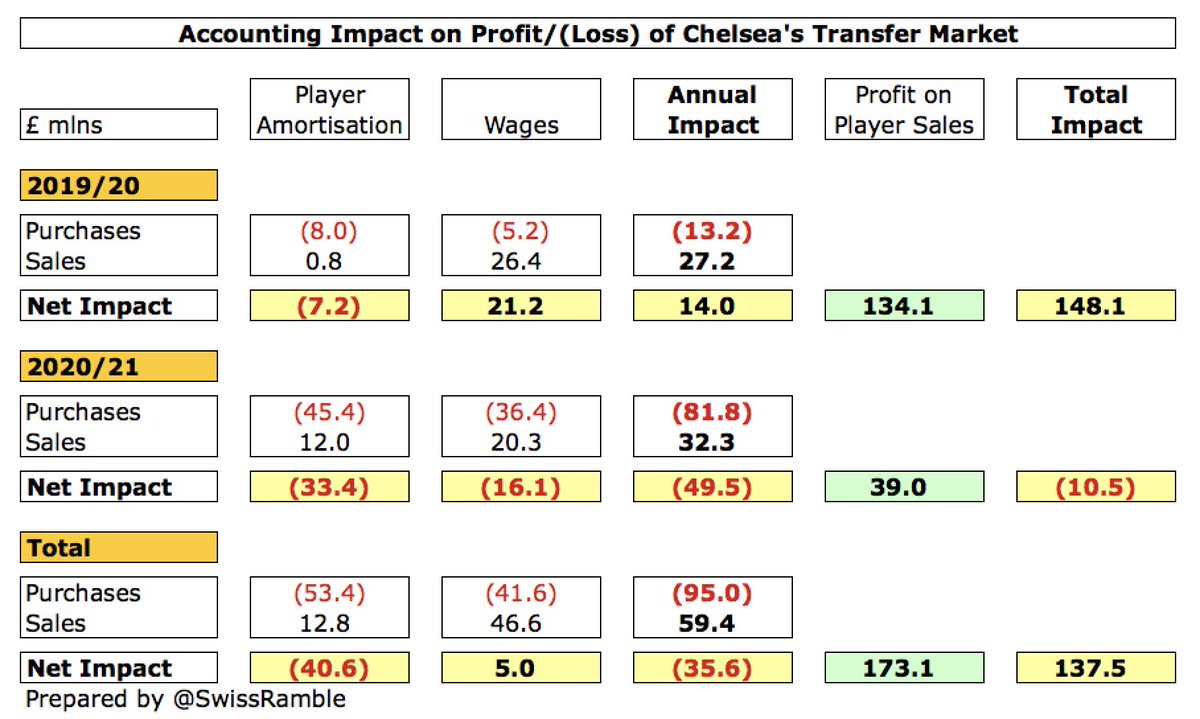

The impact on #CFC profit and loss account will be driven by two factors: (a) wages of the new purchases, which I have estimated as £42m for the last two years; (b) player amortisation, the annual cost of writing-off transfer fees, which is £53m. This adds up to annual £95m cost.

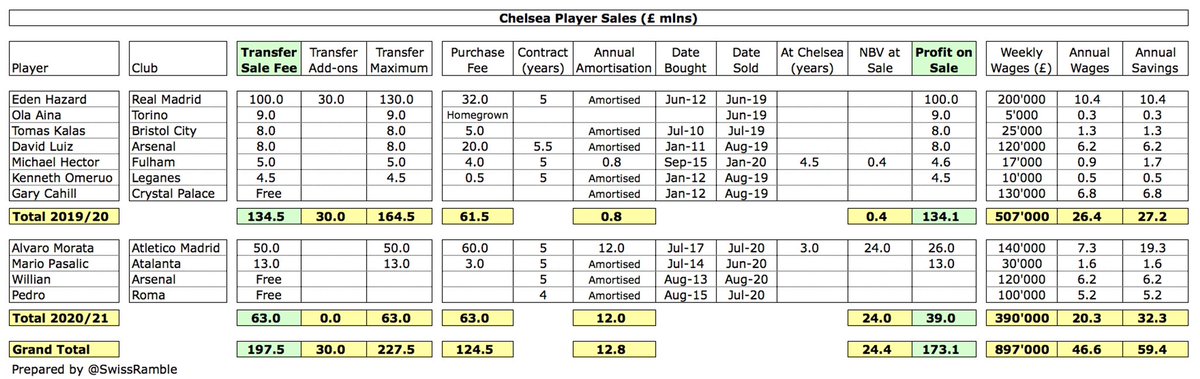

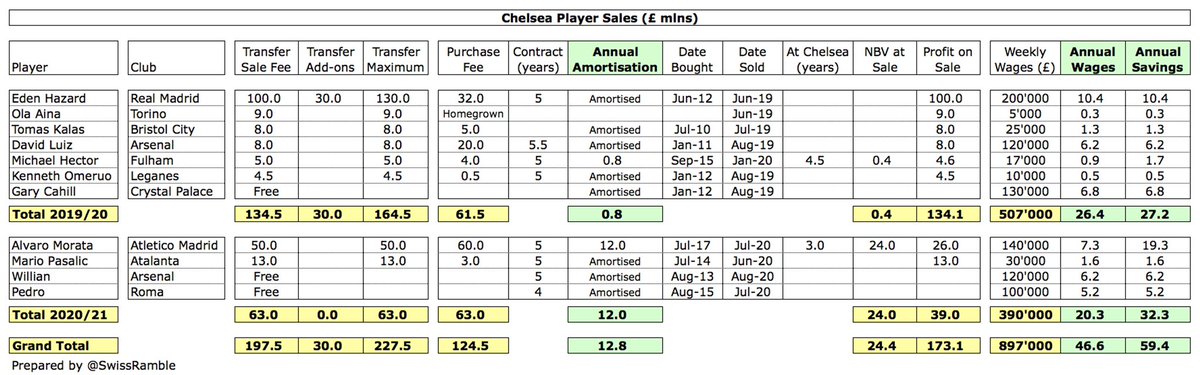

Against that, #CFC have sold players for £198m over last two years, mainly Eden Hazard £100m (excluding add-ons) and Alvaro Morata £50m, booking an estimated profit from those sales of £173m. The profit is so high, as most departing players were fully amortised in the accounts.

In addition, #CFC benefit from reducing their wage bill and player amortisation for those exits, even when no transfer fee received, e.g. Gary Cahill, Willian and Pedro. My estimates (last 2 years) are annual savings of £46m wages and £13m player amortisation, so £59m in total.

At this point, I should probably explain how player trading is shown in a club’s accounts. The key point here is that when a player is purchased costs are spread over a few years, but any profit made from selling players is immediately booked to the accounts.

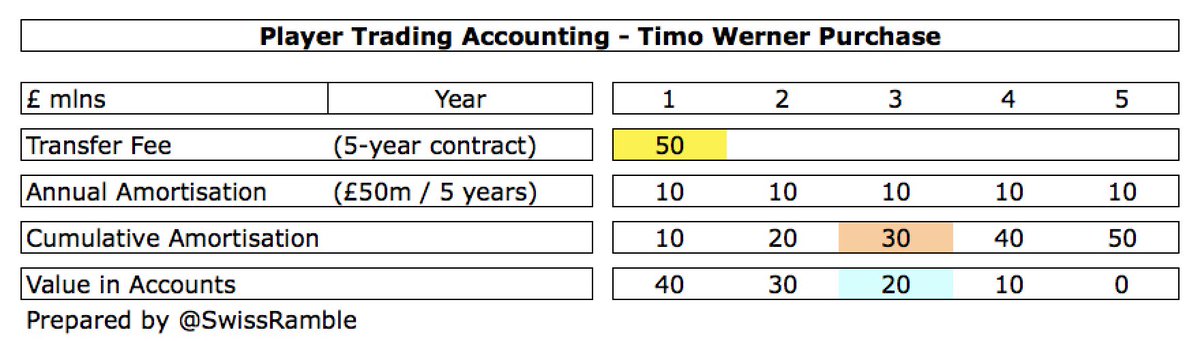

Basically, football clubs consider players to be assets, so do not fully expense transfer fees in the year a player is purchased, but instead write-off the cost evenly over the length of the player’s contract via player amortisation (note: not the same as stage payments).

For example, Werner was bought for £50m on a 5-year contract, so annual amortisation in the accounts would be £10m, i.e. £50m divided by 5 years. This means that his book value reduces by £10m a year, so after three years his value in the accounts will be reduced by £30m to £20m.

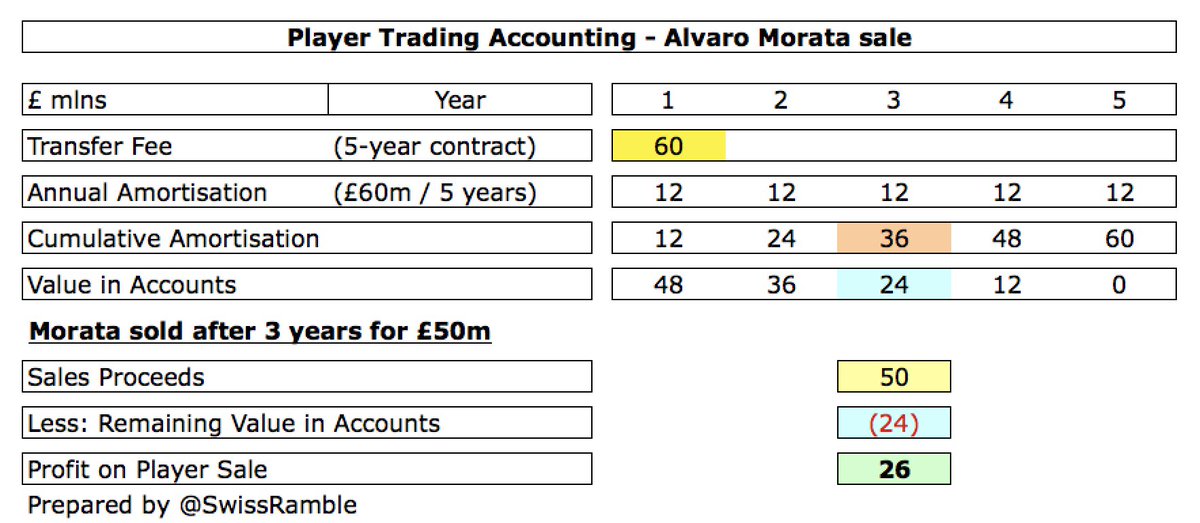

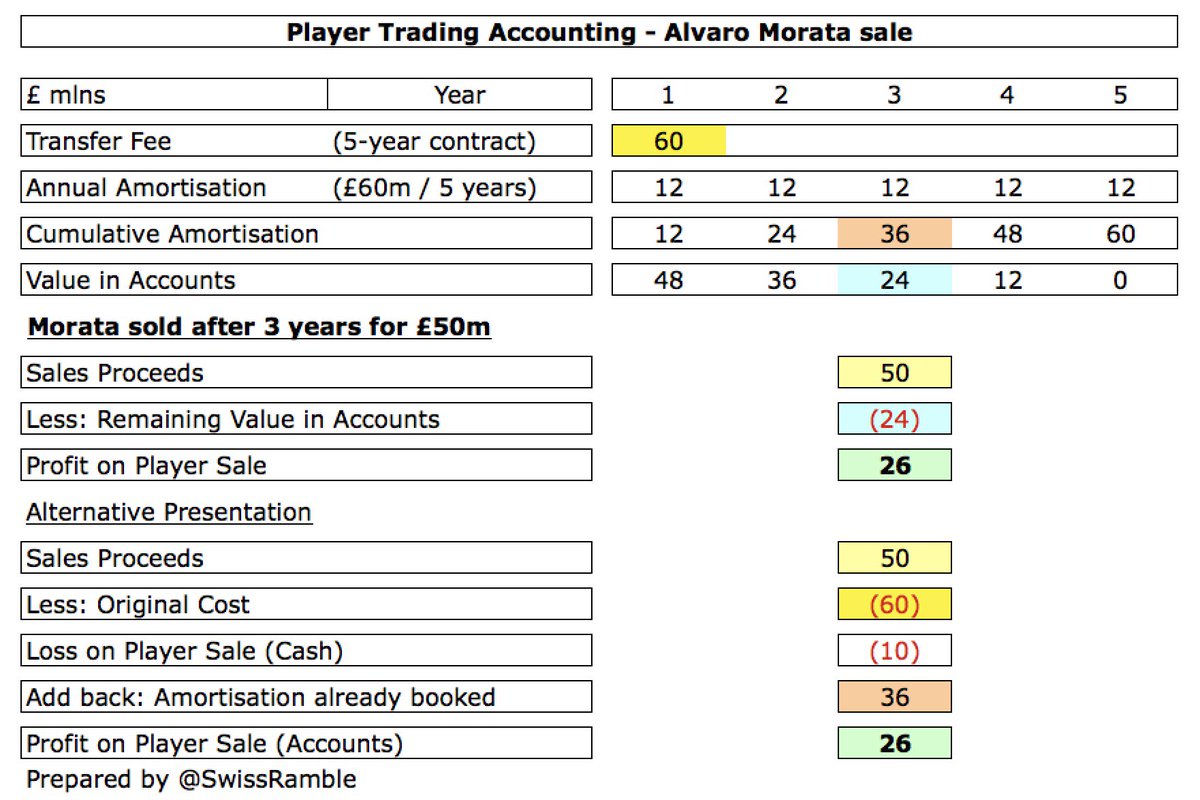

When Morata was sold for £50m, his value in the accounts after 3 years was £24m (after reducing his £60m cost by £36m amortisation), so the profit on sale from an accounting perspective was £26m – even though the sale price was lower than the purchase price.

Another way of looking at this is that the cash loss was £10m (sales proceeds of £50m less £60m purchase price), but we then add back £36m of player amortisation already booked to the accounts to give the £26m accounting profit. As the late, great Sid Waddell said, “Magic darts!”

So the overall result of #CFC transfer activity for last 2 years in the accounts is a net cost increase of £36m, with player purchases growing the cost base by £95m, partly offset by £59m reduction from sales. This will be more than offset by £173m profit on player sales.

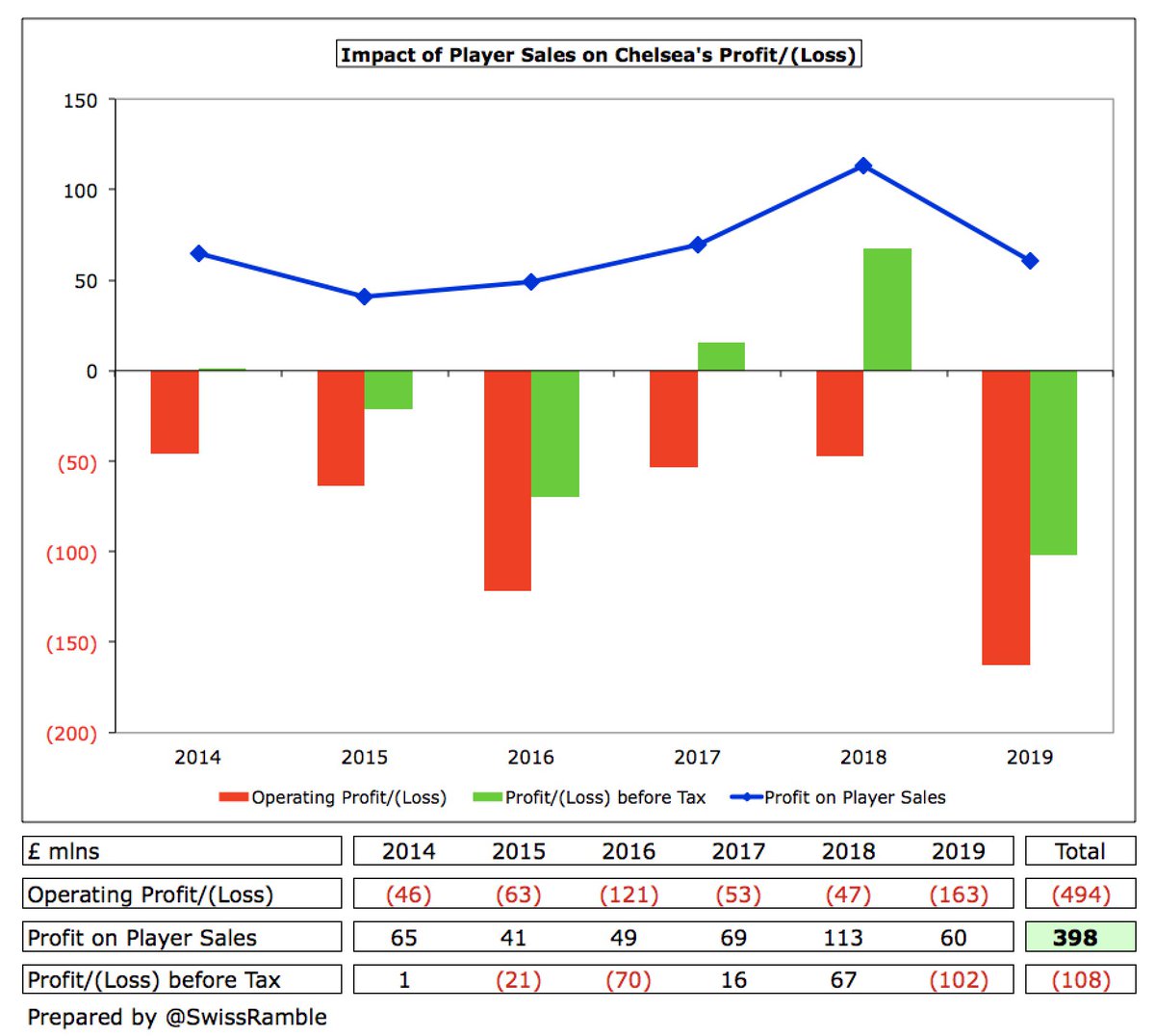

This approach is nothing new for #CFC. In fact, over the last 6 years, they have reported a hefty £494m operating loss, but have largely offset this with an impressive £398m profit from player sales, resulting in pre-tax losses of “only” £108m.

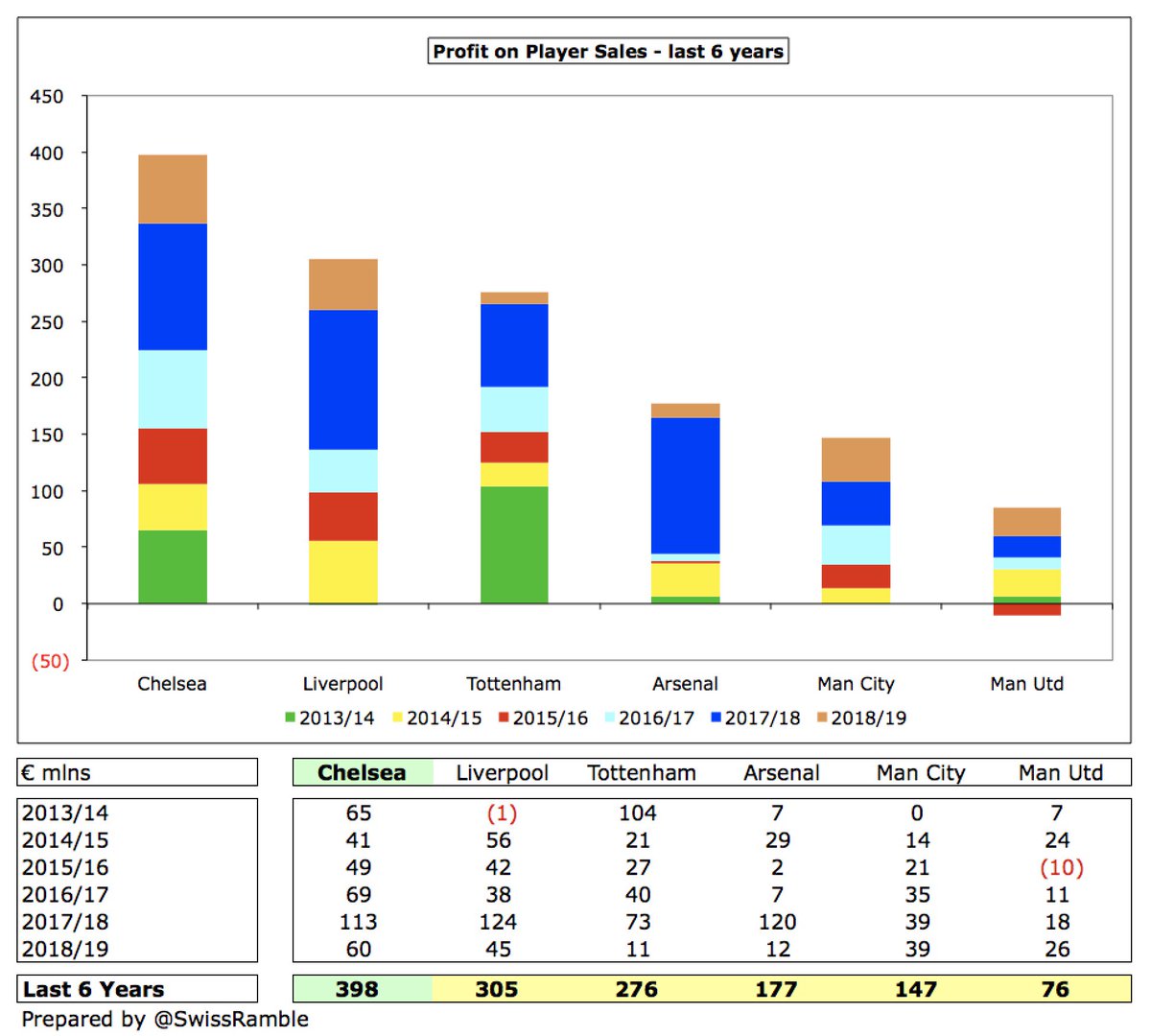

#CFC business model is far more reliant on player sales than any other major English club. In the last 6 years, their £398m from this activity is nearly £100m more than the next highest ( #LFC £305m & #THFC £276m) with the others much lower ( #AFC £177m, #MCFC £147m & #MUFC £76m).

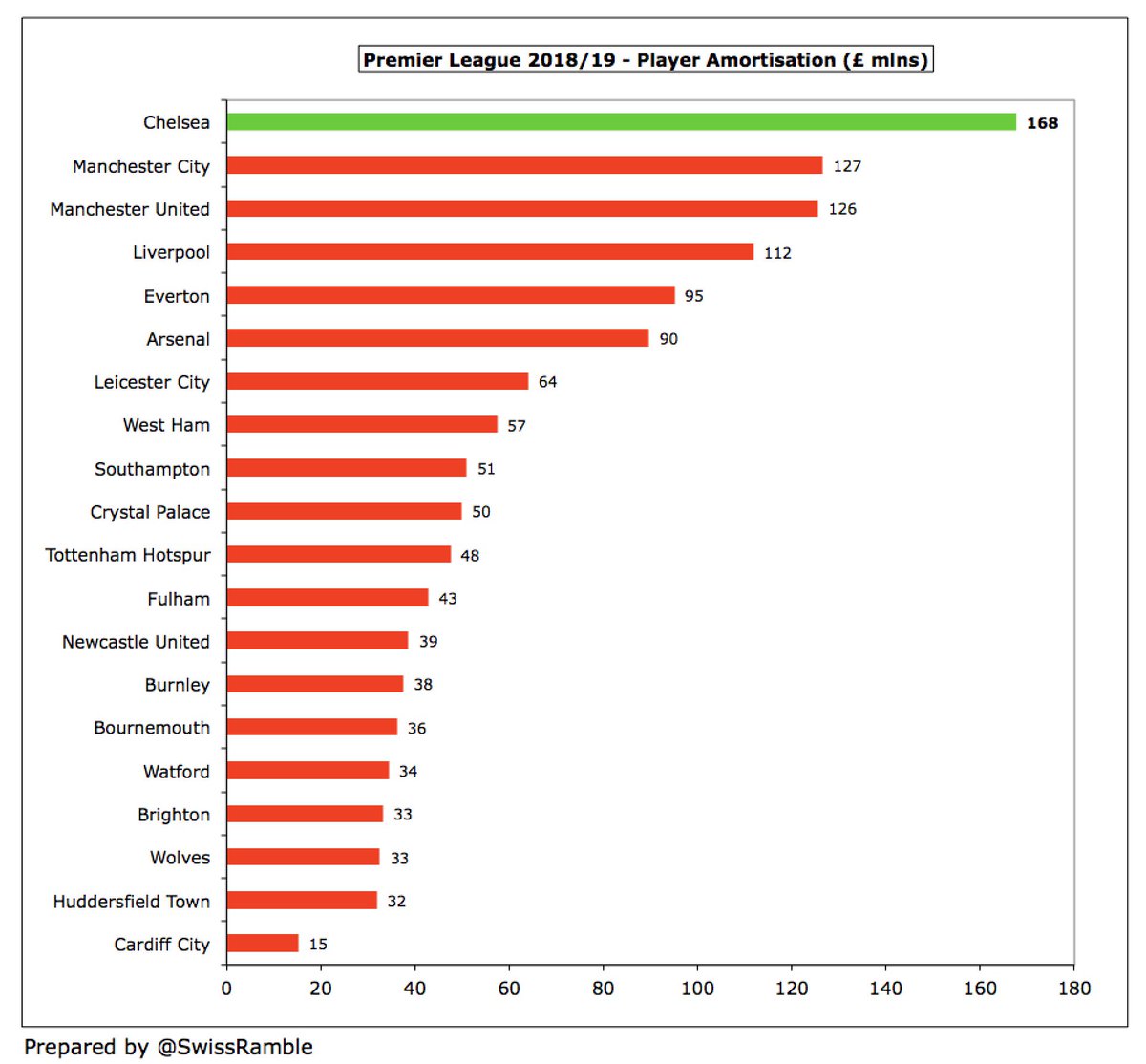

Obviously, there’s no such thing as a free lunch, so clubs eventually have to pay the cost of a spending spree in the transfer market via higher player amortisation. Indeed, #CFC £168m was by far the highest in the Premier League in 2018/19, ahead of #MCFC £127m and #MUFC £126m.

To an extent, #CFC are also playing catch-up, by spending again after last summer’s FIFA transfer ban, linked to a breach of regulations on registration of Academy players, meant that they were only allowed to spend £40m to acquire previous loanee, Mateo Kovacic.

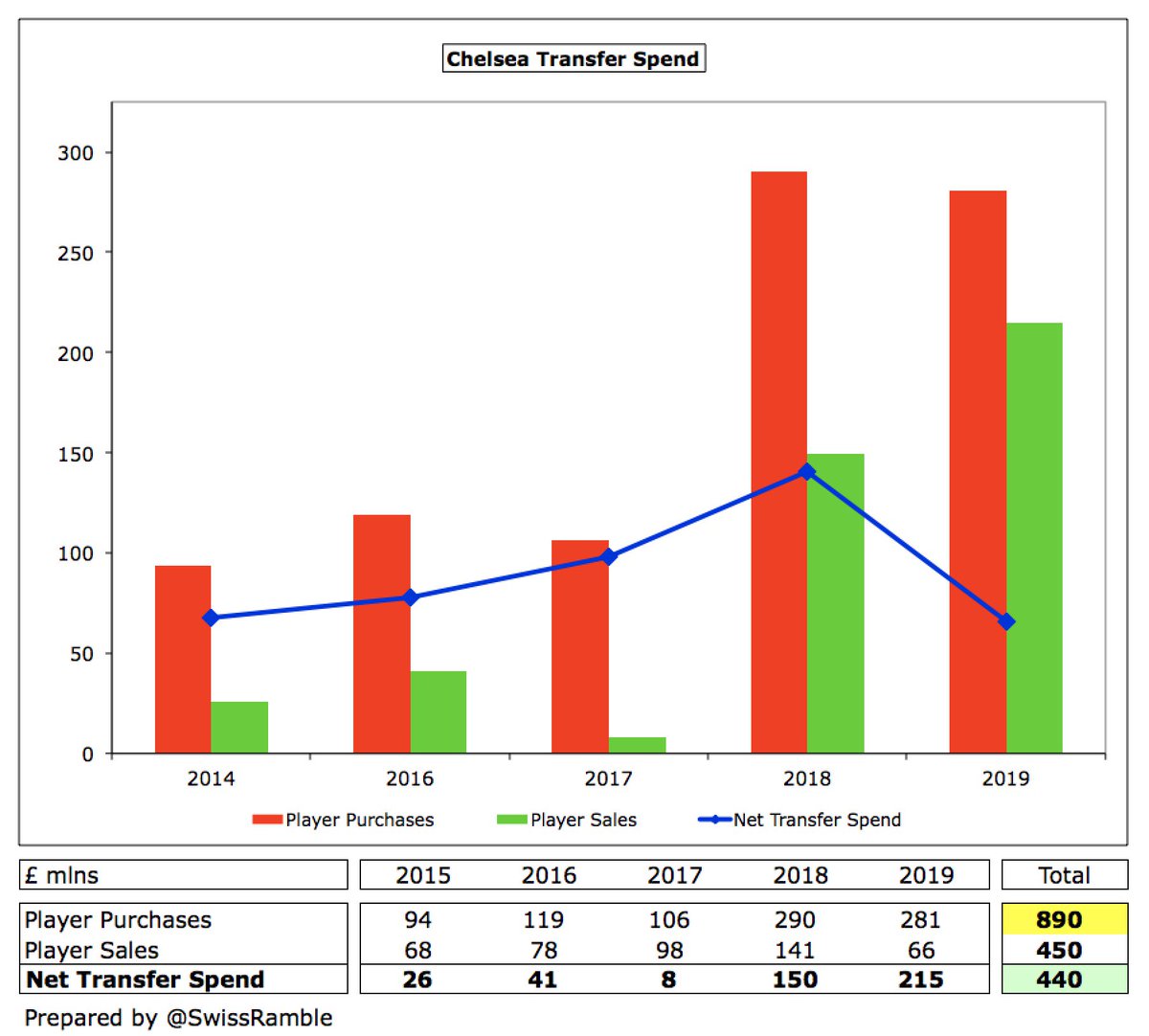

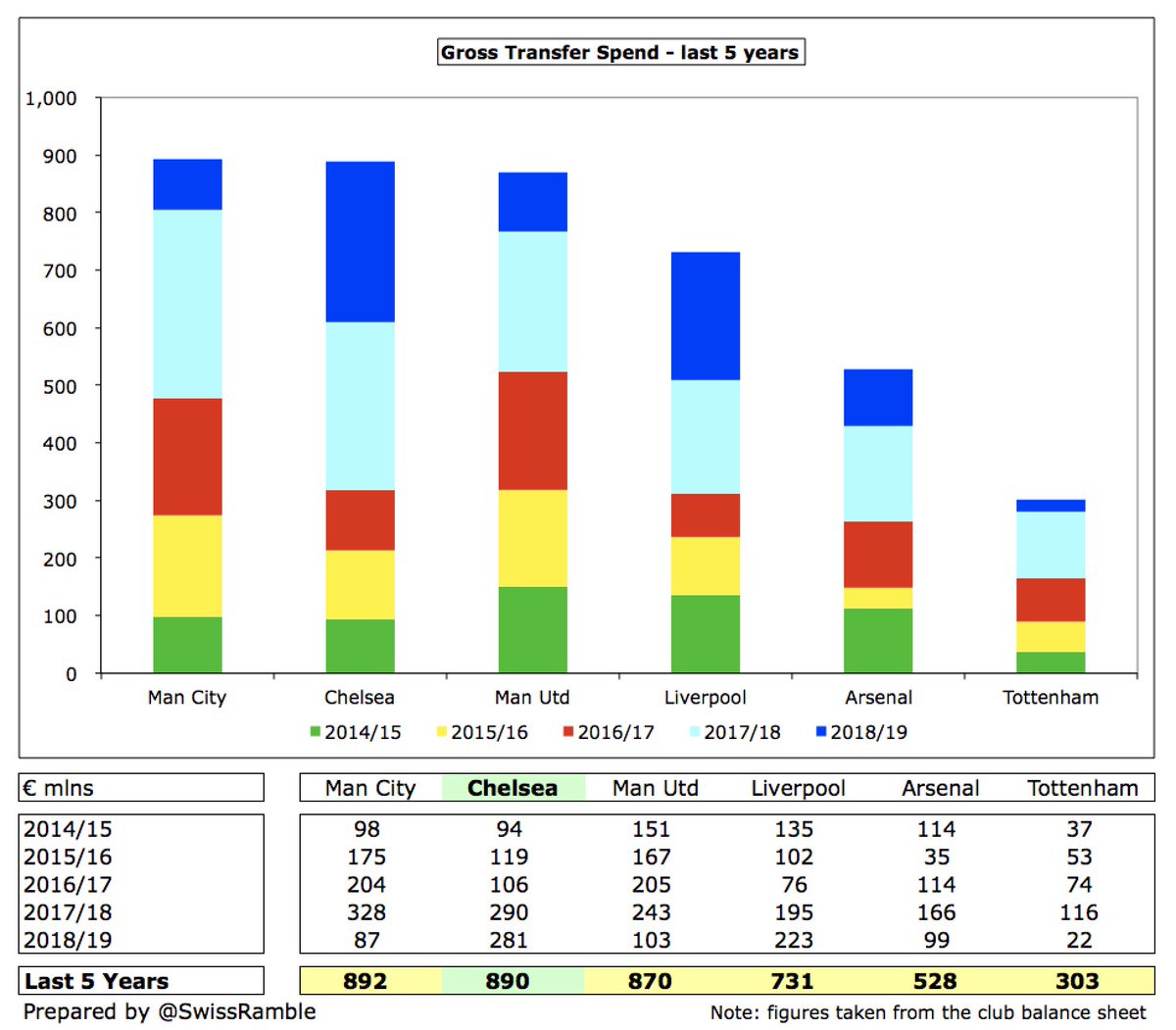

Before the transfer ban, #CFC had splashed out £890m in the last 6 years on player purchases, though this was reduced to £440m net spend after receiving £450m for player sales. Interestingly, the last 2 years before the ban saw expenditure of £290m in 2018 and £281m in 2019.

To keep up with the Manchester clubs, it could be argued that #CFC have to spend big, as their £890m over the last 6 years is almost exactly the same as #MCFC £892m and just ahead of #MUFC £870m. Long way ahead of rest of Big 6: #LFC £731m, #AFC £528m and #THFC £303m.

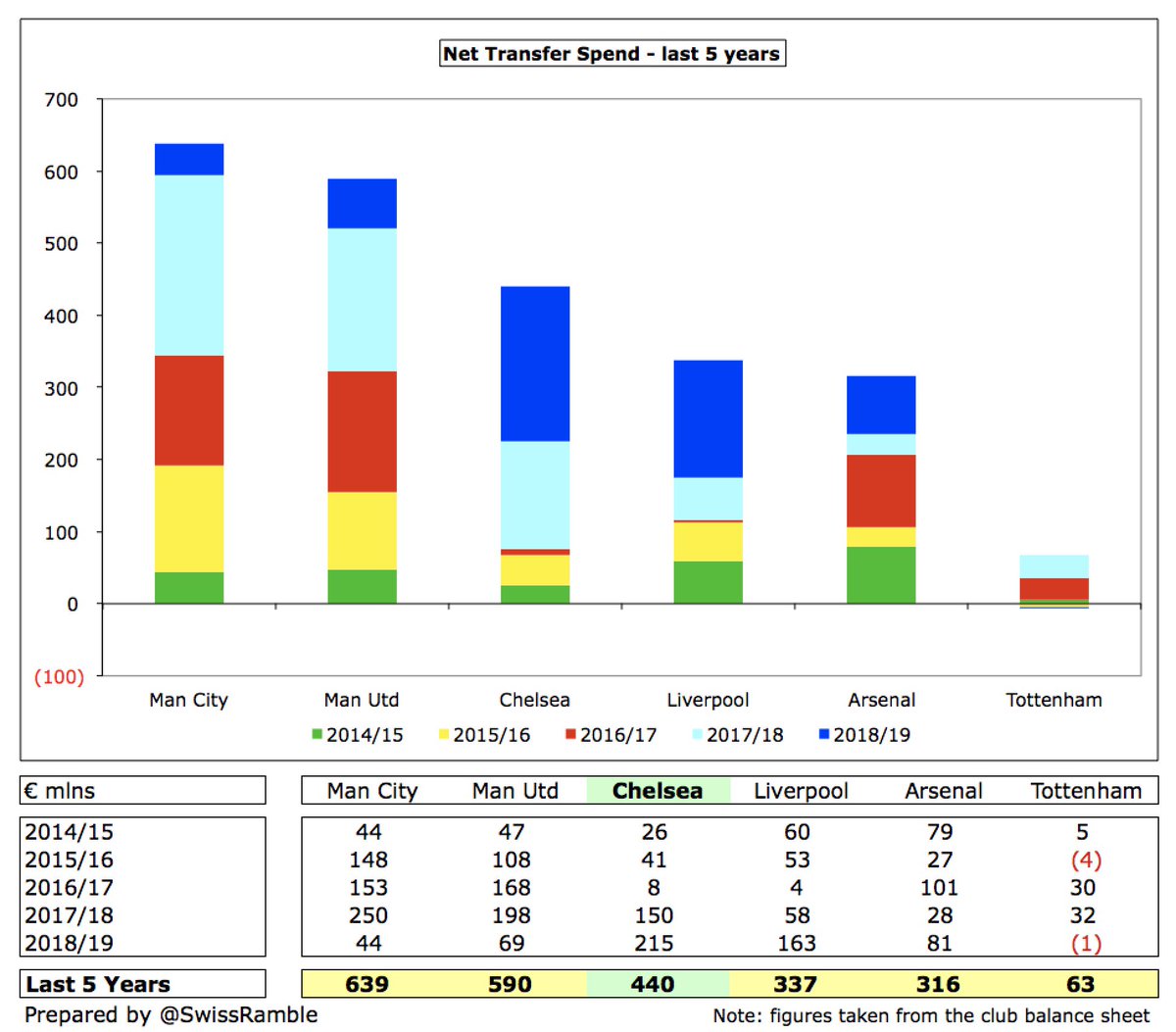

However, the picture is a bit different for net spend, thanks to #CFC ability to generate profits from player sales, as their £440m is a fair way below #MCFC £639m and #MUFC £590m, though is still comfortably ahead of #LFC £337m, #AFC £316m and #THFC £63m.

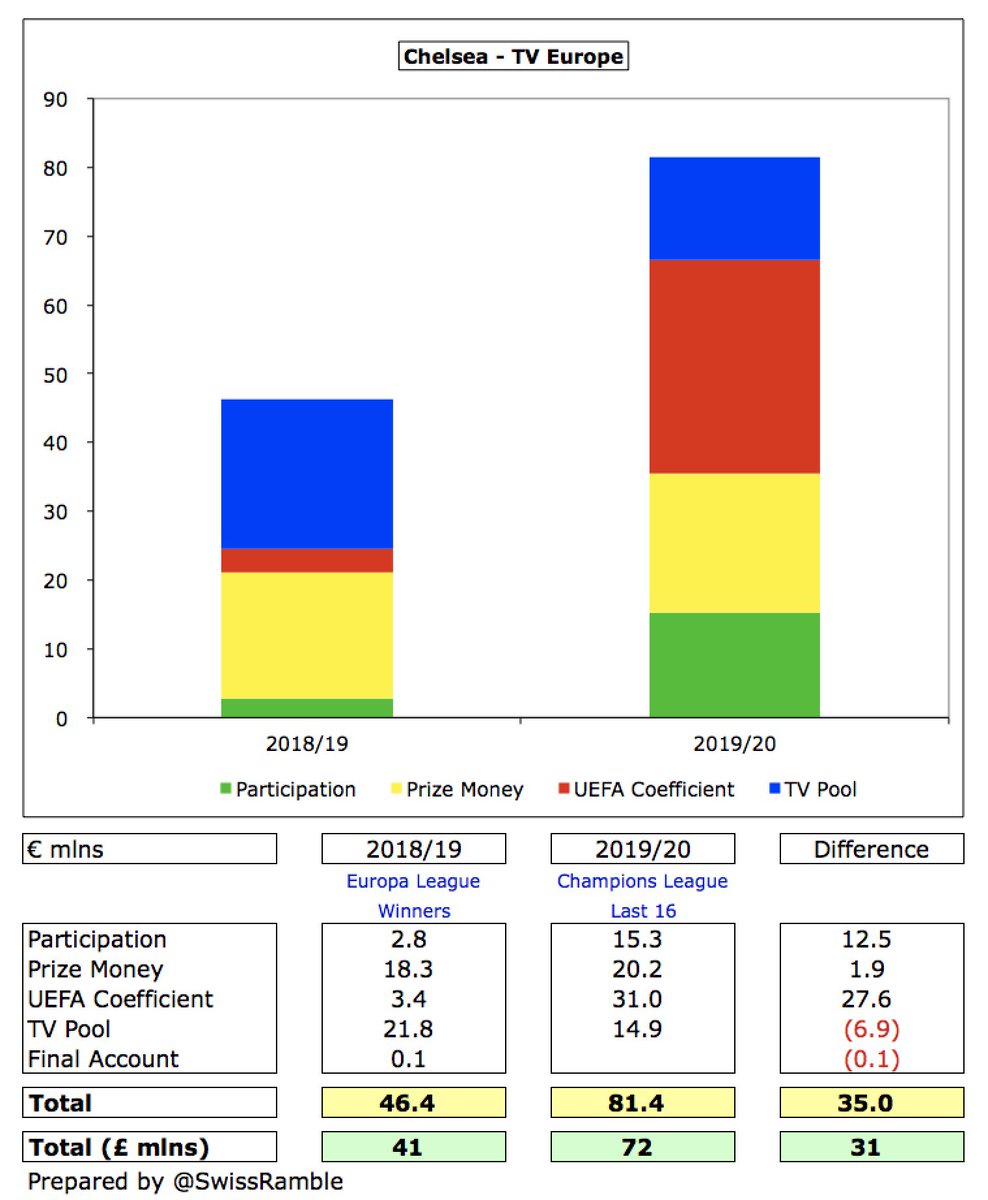

The other major boost for #CFC accounts is their return to the Champions League. In 2018/19 they earned £41m TV money for winning the Europa League, but I estimate they will receive £72m for reaching the Champions League last 16 in 2019/20, which is a revenue increase of £31m.

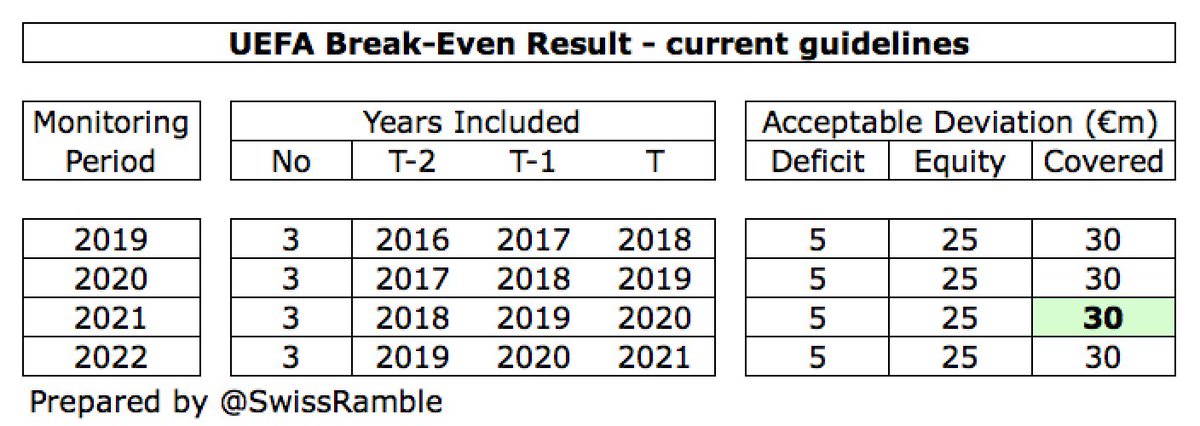

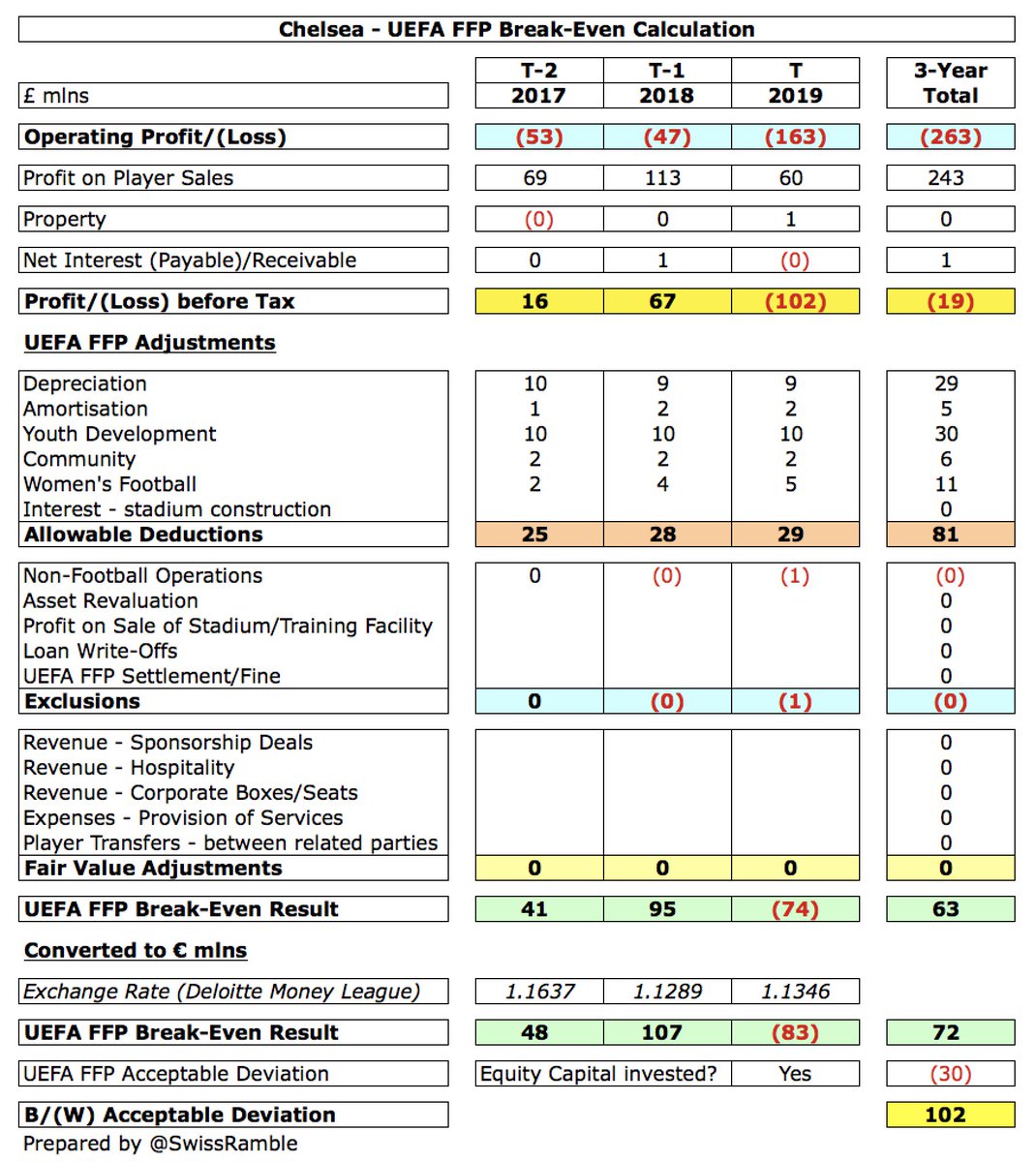

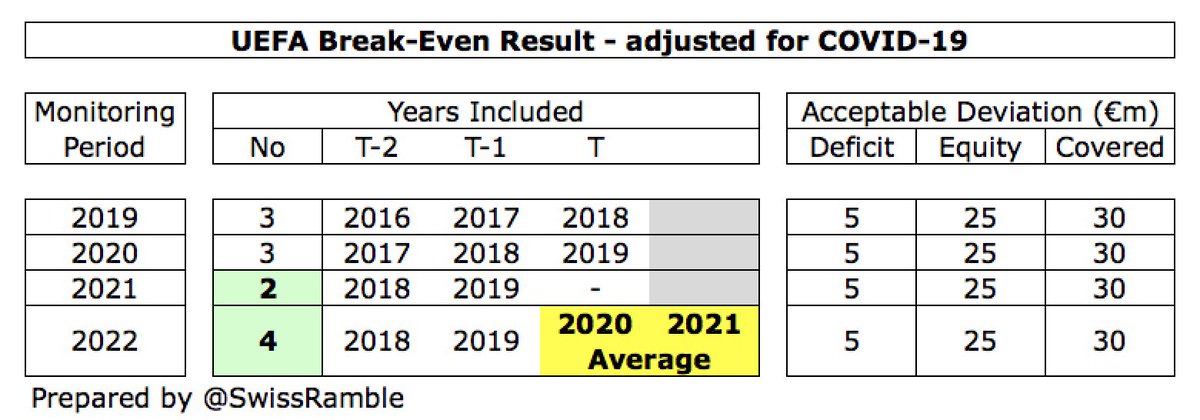

Current FFP rules limit club losses to a maximum €30m over a 3-year monitoring period, so long as €25m of that loss is covered by the owner via an equity purchase, e.g. 2021 monitoring period is 2018, 2019 and 2020. Otherwise, maximum loss (“break-even deficit”) is just €5m.

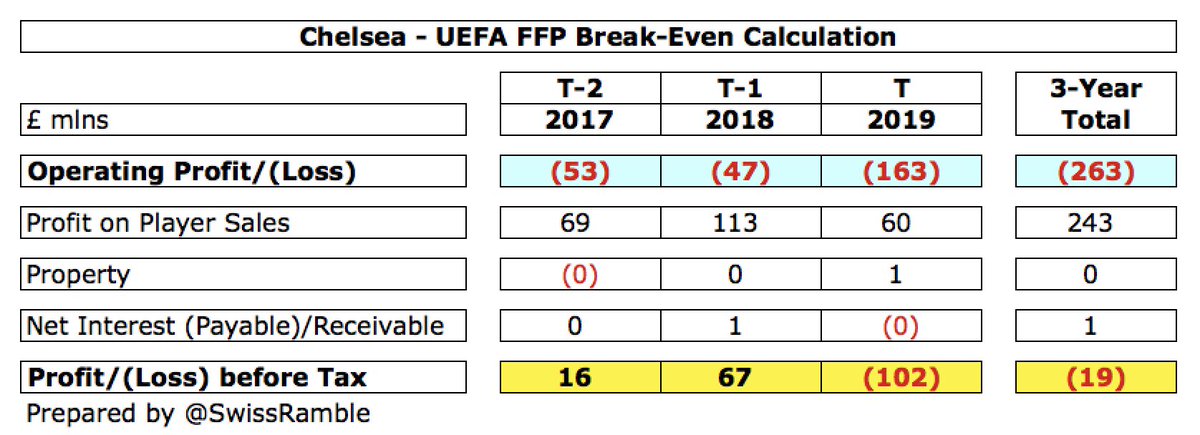

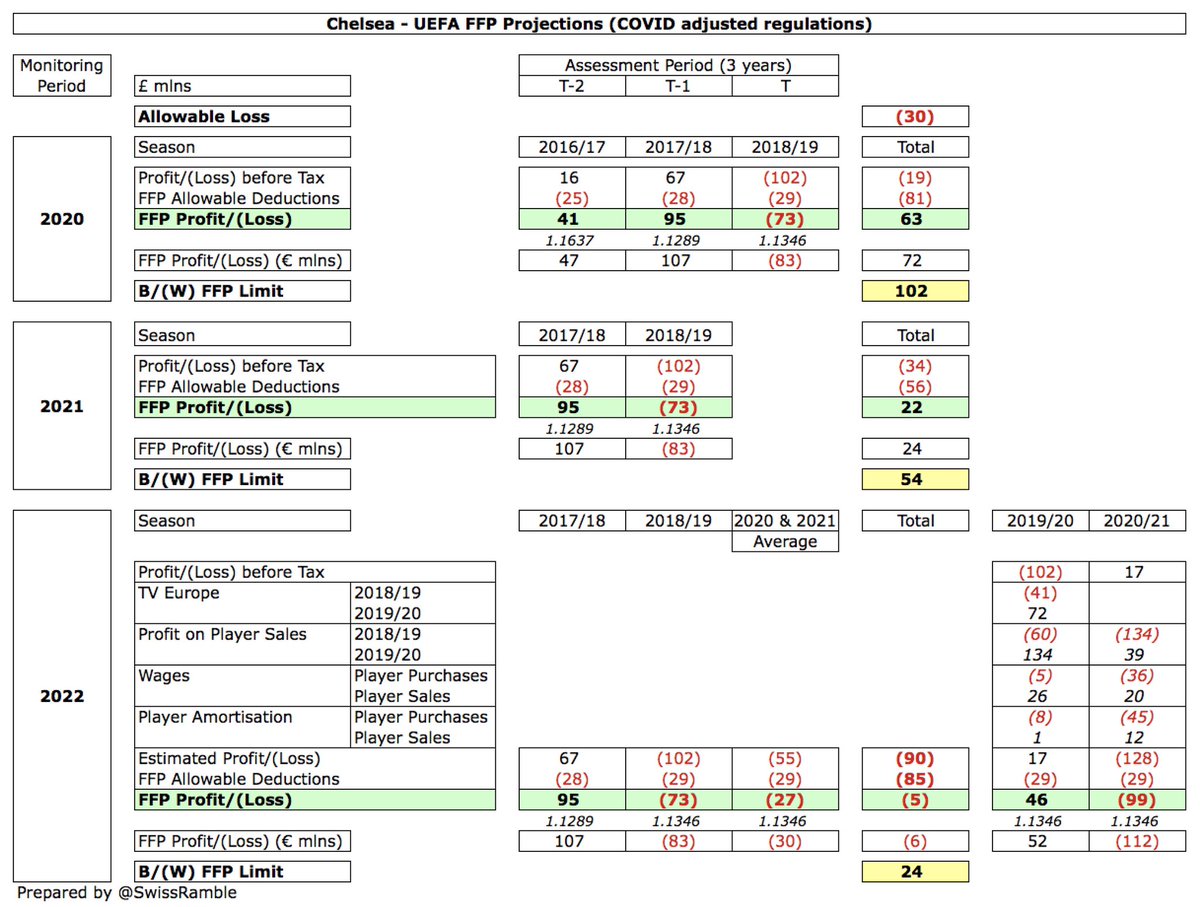

#CFC had a huge £263m operating loss in last 3 years, but largely offset this with £243m profit on player sales to give a £19m loss before tax. So their £102m loss in 2019 was essentially compensated by £67m profit in 2018 and £16m profit in 2017.

As a reminder, the losses assessed for FFP are not the same as those published in a club’s accounts. UEFA do not want to discourage “healthy” expenditure, so many expenses are excluded from the break-even calculation, though some “revenue” items are also deducted.

Expenses excluded from FFP calculation include depreciation, amortisation (except on players), youth development, community, women’s football and interest incurred on loans for stadium/training ground construction (until the asset is completed and ready for use).

On the revenue side, there are adjustments for deals with “related parties” not done at “fair value”, i.e. deducting any excess (not the entire agreement) from income. These might be sponsorships, hospitality or corporate boxes/seats.

I estimate that #CFC can deduct £81m expenses over the 3-year monitoring period. This was £29m in 18/19, comprising depreciation £9m, amortisation £2m, youth development £10m, community £2m and women’s football £5m. Added to £19m reported loss, this gave £63m break-even surplus.

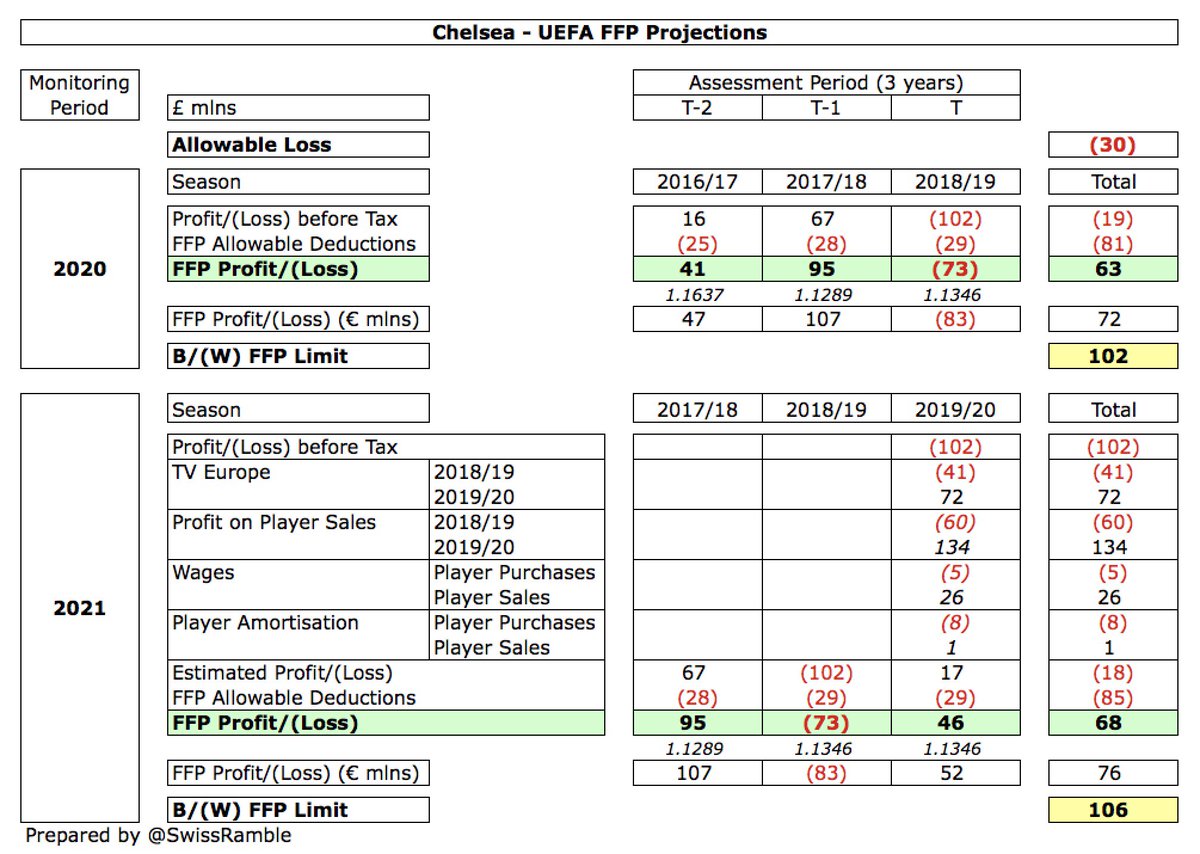

So up to the 2018/19 accounts #CFC were absolutely fine in terms of meeting UEFA’s FFP targets. However, has this status changed since they started to spend big again in the transfer market?

Well, they were still very much OK after last season’s activity. Using the 2018/19 results as a baseline, we can see that the significant profit on player sales plus the higher Champions league revenue actually resulted in an improvement for FFP with a £68m break-even surplus.

However, it seemingly all goes pear-shaped after this season’s huge transfer spend, mainly due to a fall in profit from player sales, which is currently almost £100m less than 2019/20. This results in a £126m (€143m) FFP break-even deficit, which is €113m above the €30m limit.

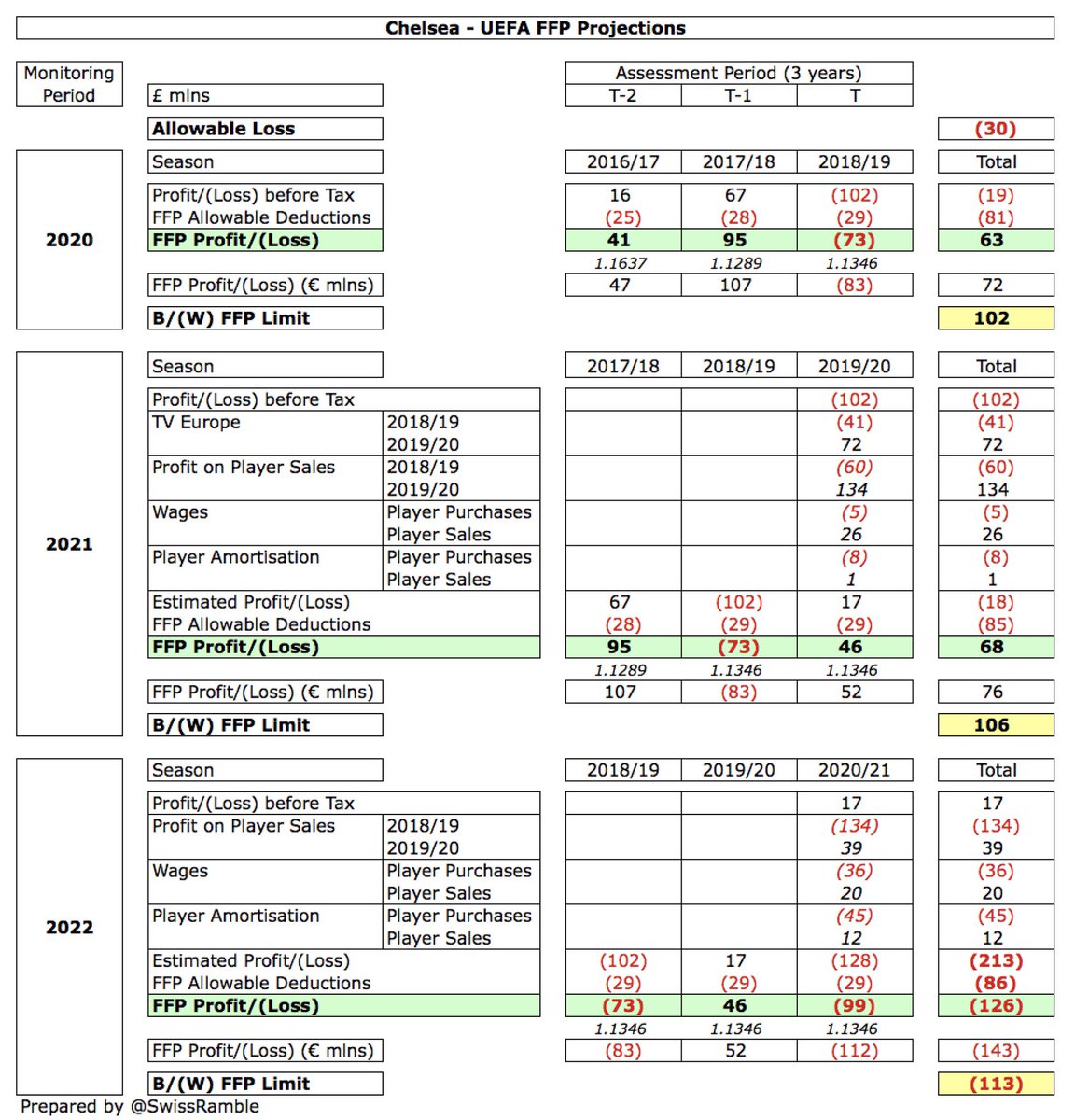

So #CFC will fail FFP? Not so fast, big boy. UEFA have made changes to the FFP regulations to “neutralise the adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by allowing clubs to adjust the break-even calculation for revenue shortfalls reported in 2020 and 2021.”

The changes mean that the 2021 monitoring period will now only cover 2 years (2018 and 2019), thus excluding the COVID-19 impacted 2020. In addition, the 2022 monitoring period will cover 4 years, though 2020 and 2021 will be assessed as a single period.

In the highly likely case that the break-even result for the 2020-2021 combined period is a loss, this will be halved for the FFP assessment. This will then be further adjusted for any revenue shortfall caused by the pandemic (compared to the 2019 revenue base).

On that basis, #CFC will only have a small £5m (€6m) FFP break-even deficit for the 2022 monitoring period, as this will cover 2018 (£95m profit), 2019 (£73m loss) and the average of 2020 (£46m profit) and 2021 (£99m loss), i.e. £27m loss. In other words, they should be fine.

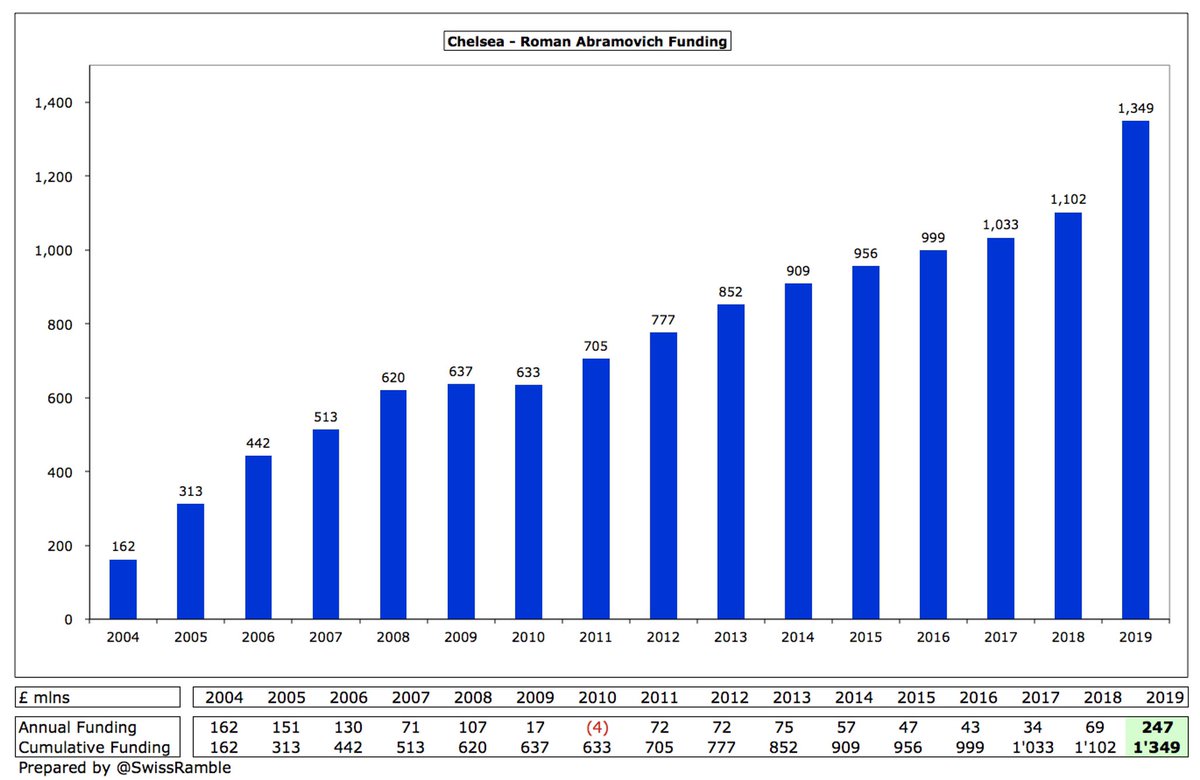

OK, enough fancy footwork in the accounts. Back in the real world someone will still have to pay the bill. Fortunately for #CFC, they can call on the “Bank of Roman”, as their owner has pumped in £1.3 bln since his arrival, including a chunky £247m in 2019.

#CFC will consider this money well spent if it drives a challenge for the Premier League – or even if it cements their spot in the to four, thus securing qualification to the lucrative Champions League, which has become a real differentiator for leading clubs.

In addition, #CFC could also easily improve their finances by selling some fringe players, such as Batshuayi, Bakayoko, Barkley, Emerson, Zappacosta and Drinkwater. They have plenty of time, as the transfer window this year only closes on 5th October.

Although UEFA have adjusted their FFP regulations with the best of intentions, one consequence seems to be that clubs with wealthy benefactors can now spend big in a buyer’s market. As they said in House of Cards, “you might very well think that – I couldn’t possibly comment”.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter