#NowWatching “Interstellar”

I may tweet about it as “a massive Nolan nut.”

(Or, you know, as somebody just enjoys talking about movies and has written a book on the subject. Whichever you prefer.)

I may tweet about it as “a massive Nolan nut.”

(Or, you know, as somebody just enjoys talking about movies and has written a book on the subject. Whichever you prefer.)

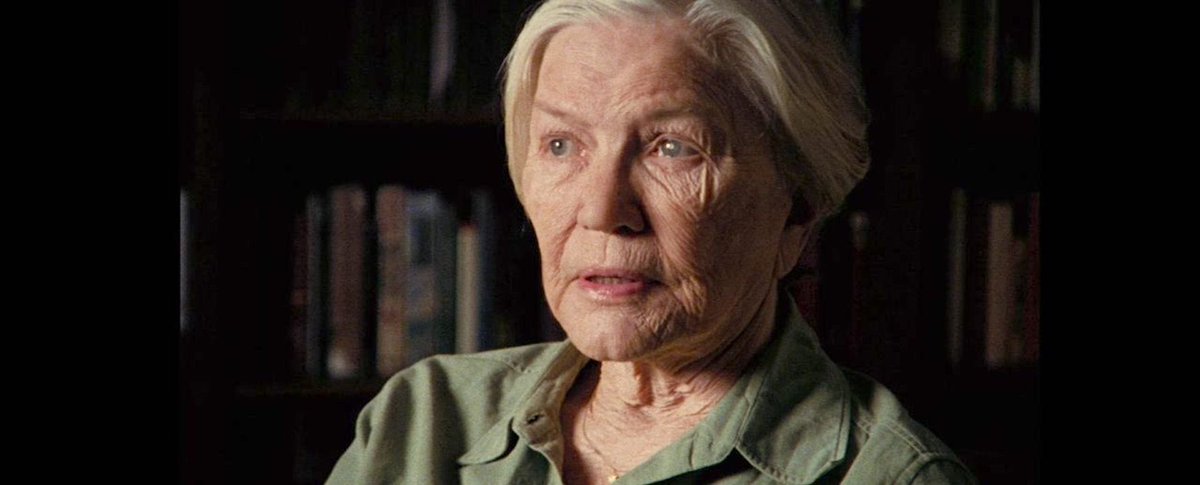

“Well, my dad was a farmer. Um, like everybody else back then.”

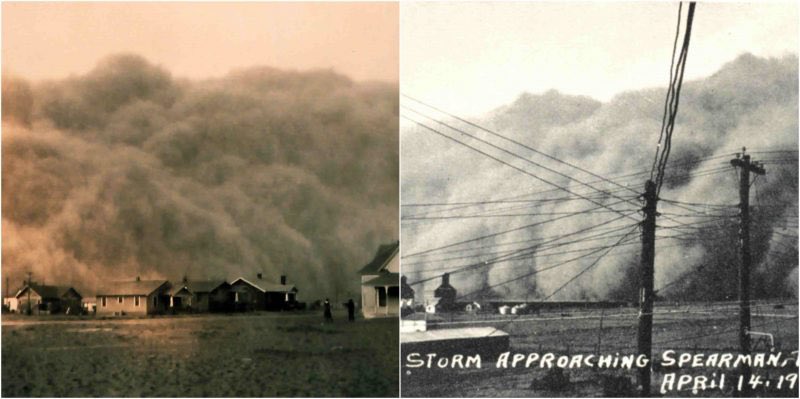

People don’t talk about how odd it is that Nolan frames his science-fiction epic as a weird docu-drama, heavily influenced by Ken Burns’ “The Dust Bowl.”

There so much else going on that it almost gets lost.

People don’t talk about how odd it is that Nolan frames his science-fiction epic as a weird docu-drama, heavily influenced by Ken Burns’ “The Dust Bowl.”

There so much else going on that it almost gets lost.

It’s possible to contextualise this as an extension of Nolan’s interests in “The Dark Knight Rises”, his obvious drawing of parallels between the 2008 crisis and the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Again, something that doesn’t really get discussed is how on-point he was on this.

Again, something that doesn’t really get discussed is how on-point he was on this.

Nolan was really the only filmmaker at his level to be making films about that experience, and turning them into crowd-pleasing blockbusters.

I mean, part of this is obviously just Hollywood history - that Depression era informed a lot of classic cinema, from which Nolan draws.

I mean, part of this is obviously just Hollywood history - that Depression era informed a lot of classic cinema, from which Nolan draws.

“Interstellar” originated as a Steven Spielberg project written by Jonathan Nolan - hence why it’s Nolan’s only post-“Prestige” project not produced by Warners. (They still managed international distribution.)

So that Americana feel is baked in; small towns, fields of gold.

So that Americana feel is baked in; small towns, fields of gold.

“You don’t believe we went to the moon?”

As with “The Dark Knight Rise”, “Interstellar” is prescient in its suggestion of a fundamentally broken America.

One looking backwards rather than forwards, lost in conspiracy theories and anti-intellectualism.

As with “The Dark Knight Rise”, “Interstellar” is prescient in its suggestion of a fundamentally broken America.

One looking backwards rather than forwards, lost in conspiracy theories and anti-intellectualism.

“Interstellar” is sympathetic to the plight of rural America in this financial and economic crisis, but wary of the dangers of small-mindedness that might creep in.

Compare it to the similarly cynical-but-Americana-tinted portrayal of Kansas in “Man of Steel” the previous year.

Compare it to the similarly cynical-but-Americana-tinted portrayal of Kansas in “Man of Steel” the previous year.

“Interstellar” ultimately understands Tom’s anger and resentment, his nostalgia and his stubbornness.

However, it refuses to condone it when he uses his frustrations to justify endangering the lives of family and the future of his children.

However, it refuses to condone it when he uses his frustrations to justify endangering the lives of family and the future of his children.

“We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars. Now we just look down, and worry about our place in the dirt.”

“Interstellar” is a product of the Obama era.

Whether because of that, or because of its origins with Spielberg, it’s Nolan’s most hopeful film.

“Interstellar” is a product of the Obama era.

Whether because of that, or because of its origins with Spielberg, it’s Nolan’s most hopeful film.

Indeed, the casting of McConaughey also does a lot of heavy lifting here. McConaughey can do sleazy, as in “Killer Joe.”

But McConaughey embodies wholesomeness in a way that Leonardo DiCaprio, Christian Bale, Al Pacino or even Guy Pearce simply don’t.

But McConaughey embodies wholesomeness in a way that Leonardo DiCaprio, Christian Bale, Al Pacino or even Guy Pearce simply don’t.

You’re going to want to keep this in mind next week, but:

As a product of its time, “Interstellar” still believes that the future might redeem us rather than condemn us.

It’s a humanist fable about boundless human potential, at a time when we could truly believe it.

As a product of its time, “Interstellar” still believes that the future might redeem us rather than condemn us.

It’s a humanist fable about boundless human potential, at a time when we could truly believe it.

“Something sent you here. They chose you.”

“Who’s they?”

Like “The Prestige”, it’s possible to read “Interstellar” as a secular religious parable.

It’s most obvious in Hans Zimmer’s score, which is beautiful. It’s like an organ playing in a Cathedral.

“Who’s they?”

Like “The Prestige”, it’s possible to read “Interstellar” as a secular religious parable.

It’s most obvious in Hans Zimmer’s score, which is beautiful. It’s like an organ playing in a Cathedral.

“Interstellar” is structured as a religious story. There as ghosts, signs, an invisible hand, a benign and unseen benefactor. It’s no coincidence that these are “the Lazarus Missions.”

It initially feels like a story about man in communion with God. It obviously evokes “2001.”

It initially feels like a story about man in communion with God. It obviously evokes “2001.”

Of course, this religious subtext is ultimately revealed as a profound sort of humanism.

For all that Nolan is considered cynical or detached, “Interstellar” is rooted in the idea that humans might yet be saved by their own potential.

It’s heartening, and moving.

For all that Nolan is considered cynical or detached, “Interstellar” is rooted in the idea that humans might yet be saved by their own potential.

It’s heartening, and moving.

In its own way, this theme ties back into that Great Depression theme that you get with the Ken Burns lifts - a belief that, underneath it all, we’re all in this together.

If we work hard enough, if we cooperate, if we collaborate, we might get through it in the end.

If we work hard enough, if we cooperate, if we collaborate, we might get through it in the end.

Incidentally, while Nolan is frequently compared to Kubrick - a somewhat facile comparison that took root with “Inception” - it’s interesting that it’s “Interstellar” that makes for the clearest point of contrast.

In that it’s nowhere near as cold or clinical as “2001.”

In that it’s nowhere near as cold or clinical as “2001.”

I’ve talked about how I admire Kubrick’s films more than I like them. To me, Kubrick often seemed to (perhaps justifiably) believe the worst of people - especially organised in societies.

Nolan’s skeptical of narratives, but has much more faith in people’s capacity for goodness.

Nolan’s skeptical of narratives, but has much more faith in people’s capacity for goodness.

“None of them had families, huh?”

“No. No attachments. My father insisted.”

“Interstellar” believes that our connections to others are what redeem us. That’s the ultimate point of Brandt’s “love” monologue.

The idea that humanity triumphs when we see beyond ourselves.

“No. No attachments. My father insisted.”

“Interstellar” believes that our connections to others are what redeem us. That’s the ultimate point of Brandt’s “love” monologue.

The idea that humanity triumphs when we see beyond ourselves.

“Interstellar” is interesting in Nolan’s filmography, in that it compliments his critiques of men literally lost in their own selfish worlds and narratives.

Leonard in “Memento”, Borden and Angier in “The Prestige”, Cobb in “Inception.” Men who struggle to see beyond themselves.

Leonard in “Memento”, Borden and Angier in “The Prestige”, Cobb in “Inception.” Men who struggle to see beyond themselves.

As @MasterMastermnd pointed out, Nolan’s critiqued this idea of the fantasy of “great men” or “singular visionaries” in interviews.

And “The Dark Knight Rises” just ended by literally suggesting Bruce Wayne was too privileged to be the best possible Batman.

And “The Dark Knight Rises” just ended by literally suggesting Bruce Wayne was too privileged to be the best possible Batman.

“Interstellar” critiques this fantasy of “the great man” with... well, the Great Mann. Played by America’s Favourite Perpetually Lost Son Matt Damon in a rare late-career role as a villain.

Mann is presented as a hero. “The best of us.”

Mann is presented as a hero. “The best of us.”

By the way, Mann implicitly genders this critique. Even beyond his name, the character is gendered as the masculine hero of a hard science-fiction story.

He is considered rational, dynamic, heroic, unemotional. His world is “cold... stark...” It implicitly rejects “love.”

He is considered rational, dynamic, heroic, unemotional. His world is “cold... stark...” It implicitly rejects “love.”

It’s been pointed out that Nolan has his familiar tropes and conventions, the ideas that he keeps coming back to. Most storytellers do, and readily acknowledge as much.

What’s interesting is how those directors come back to those themes, how they evolve and explore.

What’s interesting is how those directors come back to those themes, how they evolve and explore.

“Inception” marks a turning point for Nolan, because it draws a bow around many of his core tropes - the dead wife, the absent father, the man who has constructed his own mythology.

It pushes those tropes to breaking point, and snaps them. It’s incredibly introspective.

It pushes those tropes to breaking point, and snaps them. It’s incredibly introspective.

In the films that followed, you see Nolan approaching those familiar tropes in different and interesting ways.

Mann would be the protagonist of an earlier Nolan film, for example, and deconstructed that way. Instead “Interstellar” looks at him from the outside.

Mann would be the protagonist of an earlier Nolan film, for example, and deconstructed that way. Instead “Interstellar” looks at him from the outside.

“You're a scientist, Brand.”

“So listen to me...”

The approach to gender “Interstellar” is interesting, particularly as it relates to the clichés of hard science-fiction.

Women are constantly told to guard their emotions, conceal their feelings lest they be dismissed.

“So listen to me...”

The approach to gender “Interstellar” is interesting, particularly as it relates to the clichés of hard science-fiction.

Women are constantly told to guard their emotions, conceal their feelings lest they be dismissed.

Brand repeatedly (correctly) points out that Coop’s decision-making is as rooted in emotion as hers, but he claims the high ground by pretending to be “objective.”

Even though he wants to see his children as much as Brand wants to see Wolf. But it’s literally “a Mann’s World.”

Even though he wants to see his children as much as Brand wants to see Wolf. But it’s literally “a Mann’s World.”

Crucially, in “Interstellar”, although both Brand and Coop (and even Mann) are making decisions based on emotional needs, Brand is correct.

And she’s correct because she’s honest about it. Yet Coop overrules her by dismissing her as overly emotional.

And she’s correct because she’s honest about it. Yet Coop overrules her by dismissing her as overly emotional.

In this respect, “Interstellar” predicts the wave of female-focused science-fiction narratives of the later part of the decade - “Star Trek: Discovery”, “Captain Marvel”, etc.

Stories that rejected the gendered cliché of masculinity-against-emotionality. https://them0vieblog.com/2019/03/06/too-emotional-interstellar-star-trek-discovery-captain-marvel-and-the-re-gendering-of-science-fiction/

Stories that rejected the gendered cliché of masculinity-against-emotionality. https://them0vieblog.com/2019/03/06/too-emotional-interstellar-star-trek-discovery-captain-marvel-and-the-re-gendering-of-science-fiction/

“Interstellar” arrived in 2014. It was a year when the neo-reactionary movement was embracing a gendered pseudo-rationalism rooted in claims of “objectivity.”

Think of the “race science” nonsense, or the desire for “objective reviews” or “facts don’t care about your feelings.”

Think of the “race science” nonsense, or the desire for “objective reviews” or “facts don’t care about your feelings.”

One of the bubbles of this culture war would play out with the boundaries of science-fiction: the Sad and Rabid Puppies hijacking the Hugo Awards to push them towards reactionary, emotionless hard science-fiction.

It’s fascinating to look at “Interstellar” in that context.

It’s fascinating to look at “Interstellar” in that context.

“Interstellar” starts out as something that looks like hard science-fiction. For the kinds of people invested in those reactionary movements, it’s rock hard. They modelled black holes and learned new things! Science!

And then?

BAM! “Love” is a force like gravity. BOOM!

And then?

BAM! “Love” is a force like gravity. BOOM!

And it’s telling how much of the backlash to “Interstellar” is rooted in a mockery of that idea that “love” might actually be worthy of treating as a universal force in a science-fiction narrative.

It’s interesting how that works.

It’s interesting how that works.

“You're feeling it, aren't you? The survival instinct. That's what drove me. it's what drives all of us. And it's what's gonna save us. Because I want to save all of us. For you, Cooper. ... I'm sorry, I can't watch you go through this. I'm sorry.”

Doctor Mann is such a sh!t.

Doctor Mann is such a sh!t.

“You're gonna save everybody Because Dad couldn't do it.”

The Murph thread in “Interstellar” is arguably what pushes the film into an epic territory, not least because it adds 45 minutes to the runtime.

Part of this is down to casting Chastain and Affleck. But it’s brilliant.

The Murph thread in “Interstellar” is arguably what pushes the film into an epic territory, not least because it adds 45 minutes to the runtime.

Part of this is down to casting Chastain and Affleck. But it’s brilliant.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter