Before this tweetstorm passes, a final cloudburst  ⭢

⭢

If you follow the research on how emigration rises with development, you might be asking: Wait, didn't I just see a paper finding the exact opposite?

If so, this thread is for you. Step in ☞

⭢

⭢

If you follow the research on how emigration rises with development, you might be asking: Wait, didn't I just see a paper finding the exact opposite?

If so, this thread is for you. Step in ☞

The short answer is that yes, you remember right. But sadly, that finding was a statistical mistake.

If you're a prof who teaches econometrics, this would make a great case study for your students.

If you're a prof who teaches econometrics, this would make a great case study for your students.

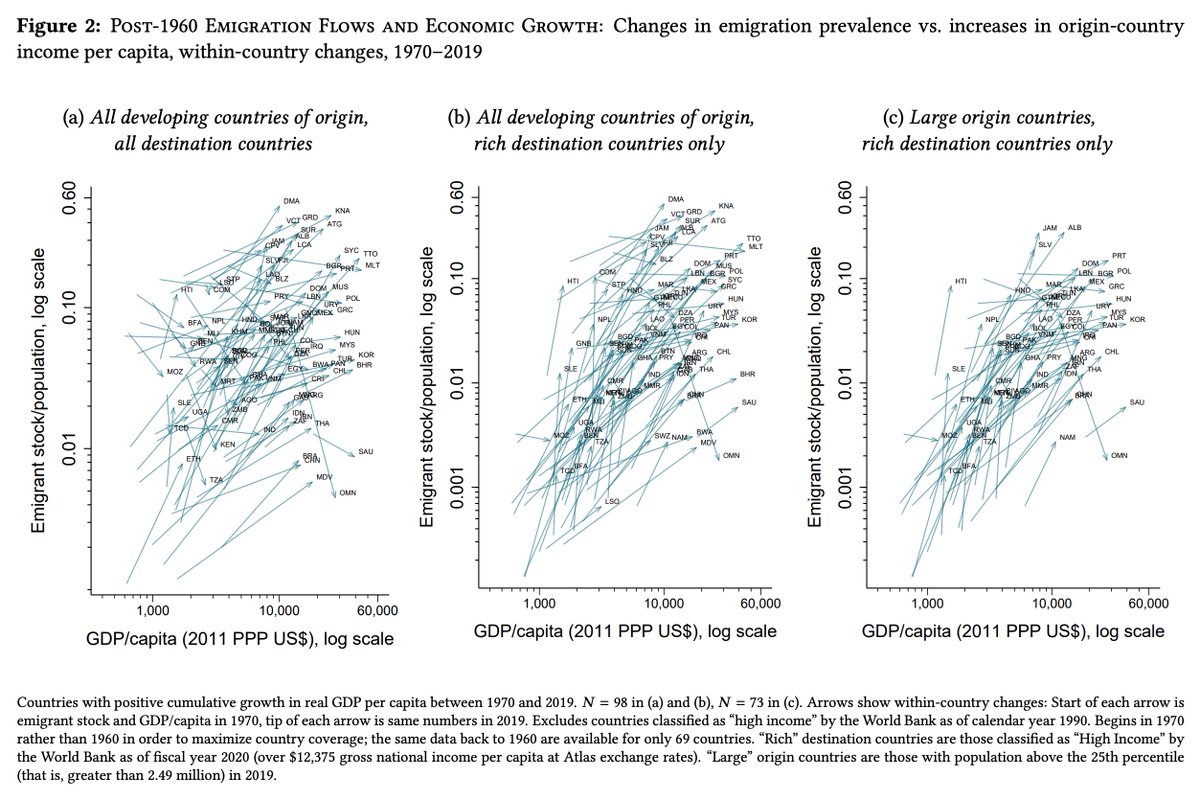

It's beyond clear that as low-income countries get richer, more people emigrate from them.

Below are the trajectories that they take over time. First all emigration, then drop poor destination-countries, then drop small origin-countries.

Papers here—> https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emigration-rises-along-economic-development-aid-agencies-should-face-not-fear-it

Below are the trajectories that they take over time. First all emigration, then drop poor destination-countries, then drop small origin-countries.

Papers here—> https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emigration-rises-along-economic-development-aid-agencies-should-face-not-fear-it

But last year, a working paper claimed that this was all terribly wrong. It claimed that if you follow countries over time, when the average developing country doubles its GDP per capita, emigration actually collapses—falling by half.

http://hdl.handle.net/10419/209721

http://hdl.handle.net/10419/209721

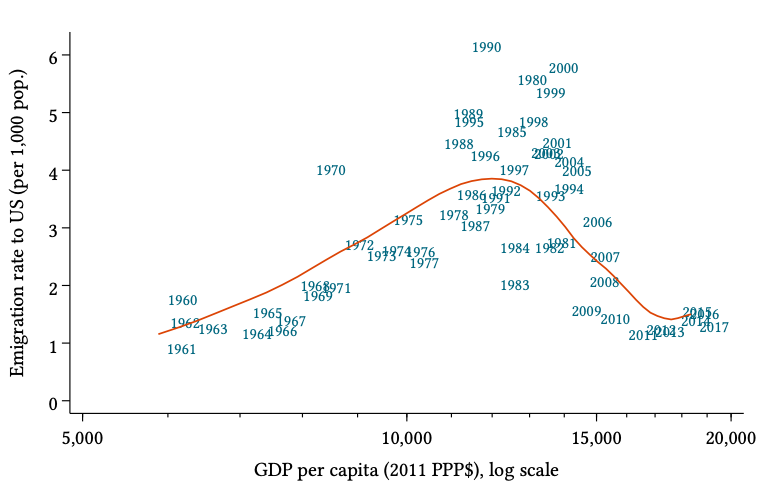

That result was truly shocking. Here is a graph from that paper, showing the cross-sectional relationship between emigration and GDP per capita. The paper was essentially claiming that the upward slope on the left is an illusion.

Quantitatively, the paper was claiming that if you were to actually follow a poor country over time, starting e.g. at $1,000 GDP per capita, its expected trajectory when GDP per capita doubles twice would look like the red line here:

But countries that have actually reached that level of development have a *vastly* higher emigration rate than the one predicted by that paper. It's up at that green circle above, one or two orders of magnitude higher.

Is it plausible that today's poor countries differ so enormously from yesterday's poor countries? Anything is possible, but the paper doesn't offer a reason why they would. That's a red flag that we need to scrutinize the methods in this analysis.

Smart, savvy development journalists like @maitevermeulen understandably believed that this statistical analysis was correct. The whole idea that emigration typically rises with development, she wrote, “turns out to be wrong” and is now “debunked” —> https://thecorrespondent.com/606/a-key-assumption-about-migration-turns-out-to-be-wrong-taking-a-few-of-my-articles-down-with-it/80227856412-a3e30880

But she did not need to write that mea culpa. Unfortunately, the finding of the underlying study was spurious. I show the math in one of my new papers: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/emigration-life-cycle-how-development-shapes-emigration-poor-countries

The mistake is straightforward, so I’ll explain it here in visuals, with a concrete example.

The mistake is straightforward, so I’ll explain it here in visuals, with a concrete example.

In brief, the study unwittingly removed from its estimates any effect of sustained increases in GDP per capita over time.

You simply cannot do that if you believe you’re measuring “the true relationship between economic development and emigration”. Lasting rises in GDP per capita *are* economic development.

Here's how it happened, using real data on migration from Mexico to the US.

This is a quintessential example of the #EmigrationLifeCycle: emigration rose with development at first, and fell much later.

Annual flows of Mexicans to the US, 1960–2017, vs. GDP/capita in Mexico:

This is a quintessential example of the #EmigrationLifeCycle: emigration rose with development at first, and fell much later.

Annual flows of Mexicans to the US, 1960–2017, vs. GDP/capita in Mexico:

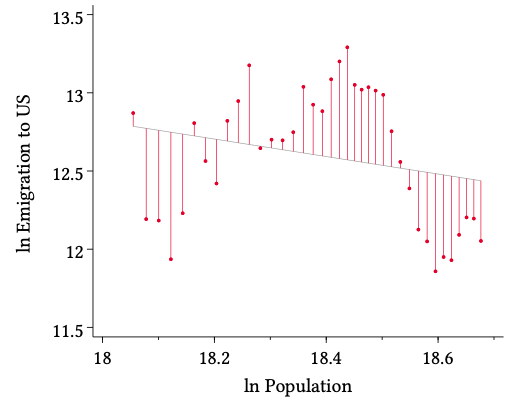

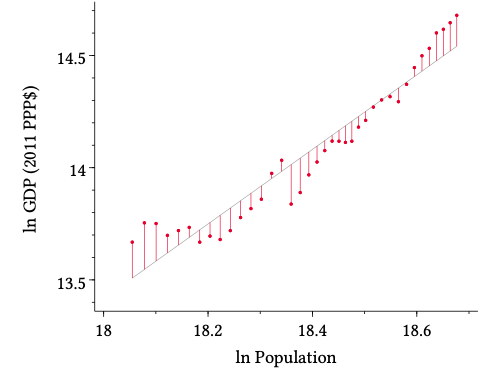

Let's analyze the data here exactly as that working paper did. We will regress the number of emigrants on GDP, controlling for population (with everything in logarithms).

First, regress emigration on population, and save the residuals (red lines):

First, regress emigration on population, and save the residuals (red lines):

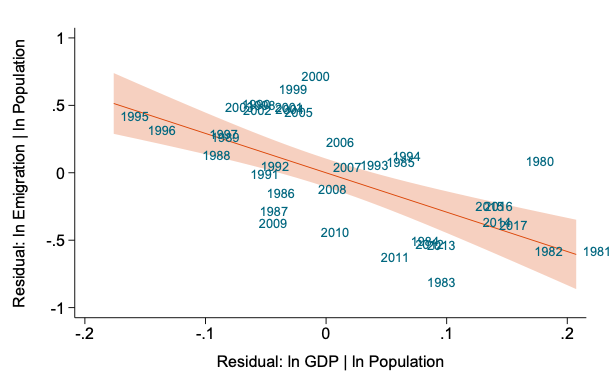

Finally, regress that first set of residuals on the second set. That's arithmetically identical to what we are doing if we regress emigration on GDP and population, then estimate the coefficient on GDP. The regression looks like this:

There is a negative relationship between GDP, for a given level of population, and emigration. It is large and highly statistically significant. This is the number estimated in that working paper, for developing countries on average.

It is also spurious. As the above figures clarify, this regression is just showing that when GDP is *above its long term trend* relative to population, then emigration is *below its long term trend*.

But that long-term trend in GDP relative to population—the thing that has been removed from this analysis—*is* economic development. There is no meaningful definition of "economic development" that does not center on incomes rising sustainably over time.

To be sure, that paper was doing an interesting analysis of the relationship between short-term *shocks* and emigration. When GDP per capita suddenly dips below long-term trend, like in Mexico during the 1990s Peso crisis, or more recently in Venezuela, emigration surges.

That's useful work, and I've never seen it documented. I hope the authors pursue that line of research because it's an area where quantitative research can make an important contribution. But that has nothing to do with the relationship between "development" and migration.

The mistake here is an age-old fallacy in econometrics. The first reference to this problem I can find is from a century ago! —> http://doi.org/10.2307/2341482

It was named, by (Nobel laureate) Clive Granger & Paul Newbold, the "spurious regressions" problem —> https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(74)90034-7

It was named, by (Nobel laureate) Clive Granger & Paul Newbold, the "spurious regressions" problem —> https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(74)90034-7

Basically regressions can turn meaningless if more than one variable in the regression contains a time trend ("nonstationary"), but we don't account for that fact.

Simple example: regress leukemia mortality on the consumption of Taylor Swift videos, over many years.

Simple example: regress leukemia mortality on the consumption of Taylor Swift videos, over many years.

You'd get a strong negative coefficient. Does @taylorswift13 cure cancer? Perhaps, who knows! But even if so, that regression wouldn't show it, because the correlation arises from the fact that both variables contain time trends.

Similarly, in the spurious regression above, both GDP and population contain a trend, but the regression fails to account for it, leading to an incorrect conclusion.

Thank you for reading! Papers linked here: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emigration-rises-along-economic-development-aid-agencies-should-face-not-fear-it

Thank you for reading! Papers linked here: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/emigration-rises-along-economic-development-aid-agencies-should-face-not-fear-it

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter