I think we, as teachers, need to be on the lookout for how our own judgment about the right way to teach might be effected by common cognitive and inductive biases. A thread...

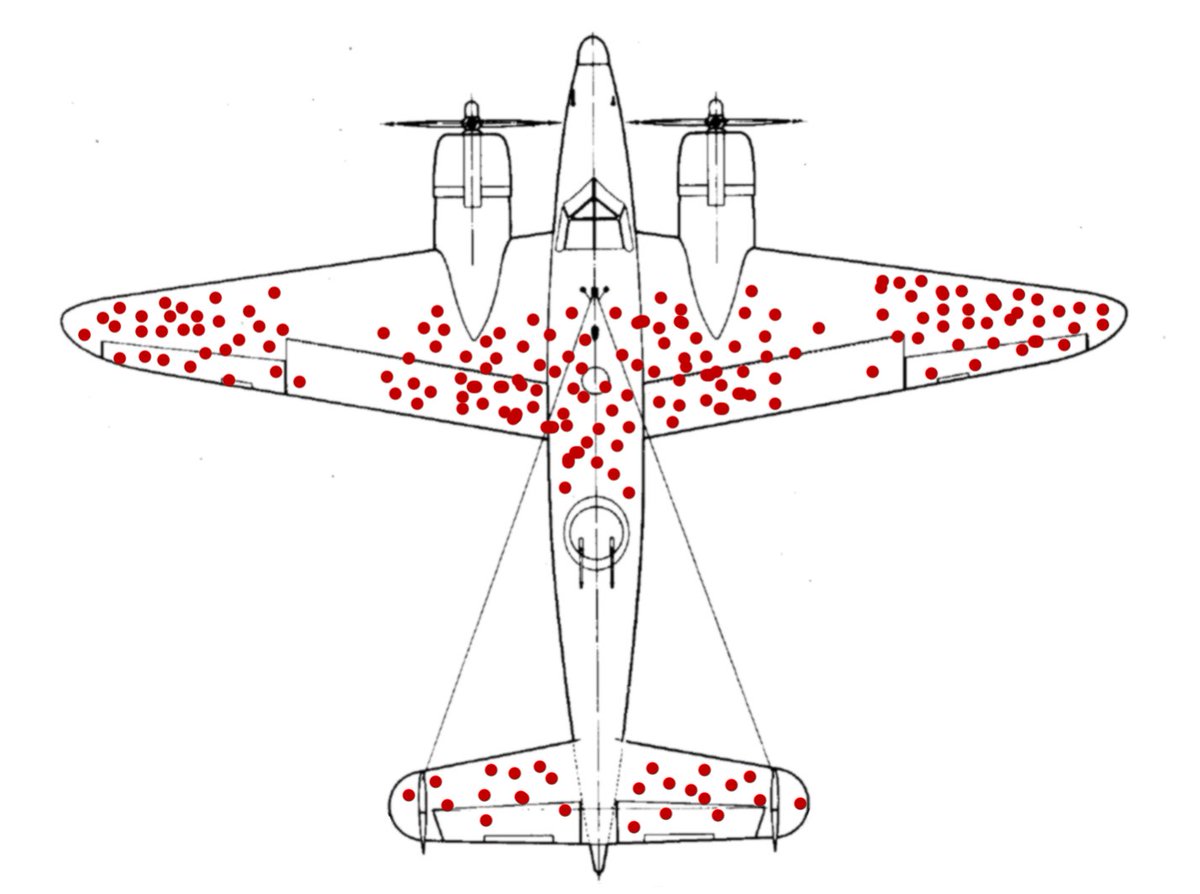

Bias #1: survivorship bias. This is the bias where you look at a population that has been selected for one reason and assume that features of that selected group represents the population at large.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Survivorship_bias

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Survivorship_bias

One example: Conservativism. Everyone who is now a professor likely enjoyed the way a topic was taught (otherwise, they wouldn't have become a professor). So they are resistant to reforms because they remember liking it being taught one way.

Second example: If one asks advanced undergrads about what attracted them to your field, you will also tend to get more conservative assessments. Why? Because you aren't surveying those people who might have majored in your field, but were turned off by the way it was taught.

Bias #2: Confirmation bias. We all have ways we like to teach. We tend to highlight evidence that reinforces that style of teaching and ignore evidence that contradicts it. This is especially dangerous when we rely on memory based judgments.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confirmation_bias

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confirmation_bias

So, if I ask you: does your style of teaching work well, you will tend to remember the successes rather than the failures. If I ask you whether this change will be good, you will tend to think of ways it will fail but not ways that it will succeed.

Because assessment of teaching and programs is very difficult, I think this one is really pernicious. I like to talk, so I will tend to highlight evidence that justifies me lecturing or dominating discussion.

Bias #3: Sunk cost fallacy. We tend to overvalue a project that we have already put work into, we throw good money after bad.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunk_cost#Fallacy_effect

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunk_cost#Fallacy_effect

In teaching, we are more likely to forge ahead with a style of teaching or a class because we've put a lot of work into it. We will put even more work into it, when our efforts would be better spent going in a different direction.

I was teaching a class on Hume, who I really like to teach. Enrollments were low, but I kept teaching it and working to make the class better. I should have given up and moved on to a different class, but I thought "I've already put so much work into this..."

Bias #4: Self-Serving biases. We tend to attribute our successes more to our own effort, but our failures to something outside our control.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-serving_bias

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-serving_bias

This often leads us to think that we are instrumental in our student's successes, but also to think that their failures are outside our control. The successful student was brought into the field by our great teaching, but the student who left just wasn't interested in the topic.

"Basis" #5: Demand effects. Psychologists worry about the possibility that subjects will infer the purpose of their study and then craft their behavior to confirm the intuitions of the experimenter. (It can also go the other way.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demand_characteristics

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demand_characteristics

I worry that a similar effect can happen when we ask for feedback from our students. They may glean that we like (or dislike) a particular style of teaching, and may craft their performance in the class to confirm our preexisting desire to teach (or not teach) in that way.

There is, of course, no magic bullet for avoiding cognitive biases. But be should be aware of them, and try to design measures for our teaching to work around them.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter