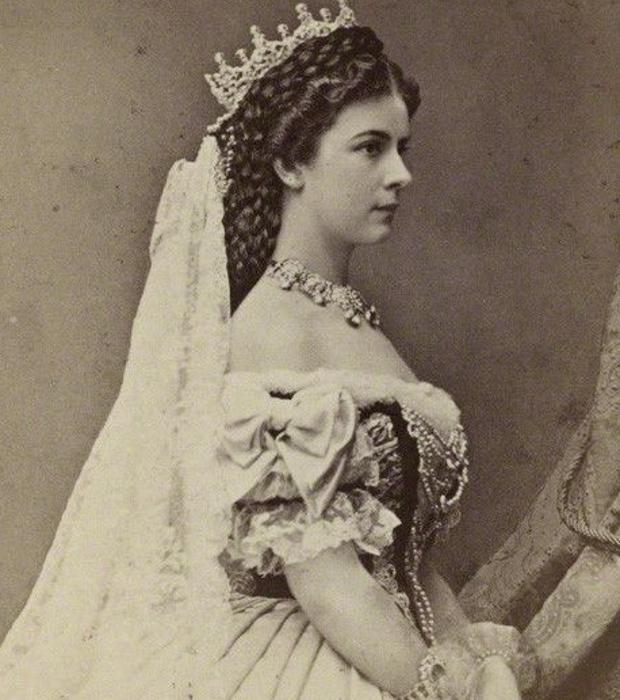

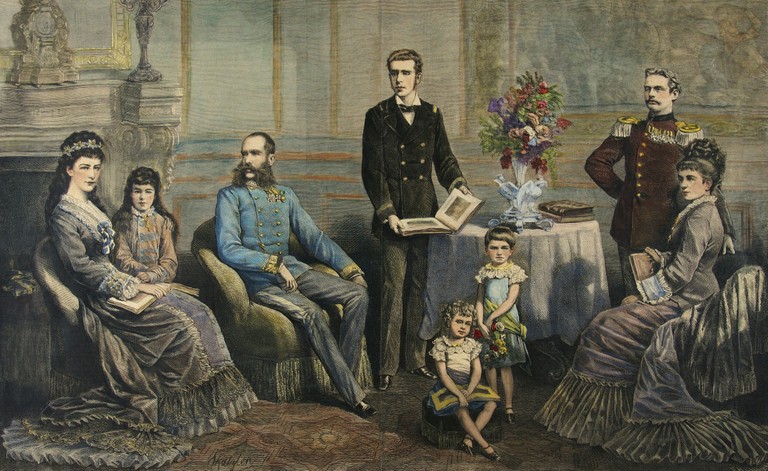

Empress Elisabeth of Austria (born Duchess Elisabeth in Bavaria; 24 December 1837 – 10 September 1898) was Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary by marriage to Emperor Franz Joseph I.

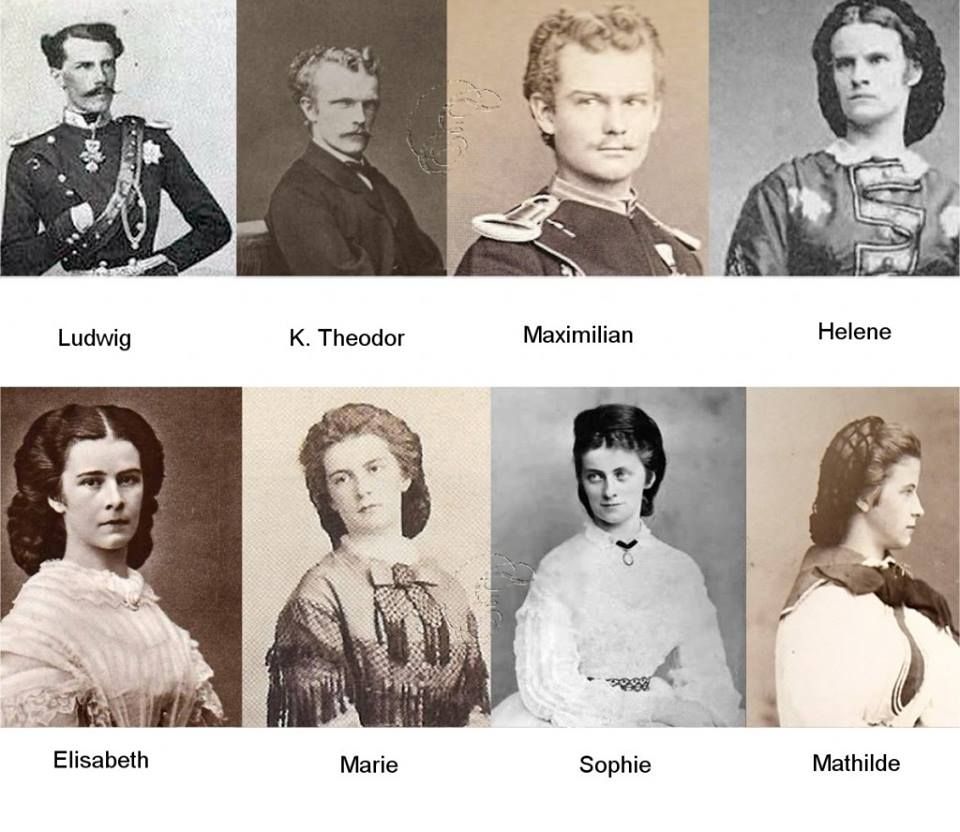

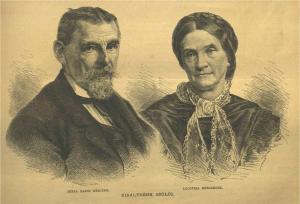

Born Elisabeth Amalie Eugenie on 24 December 1837 in Munich, Bavaria, she was the second child of Duke Maximilian Joseph in Bavaria and Princess Ludovika of Bavaria. She was born into the royal Bavarian House of Wittelsbach.

Maximilian was considered to be rather peculiar; he had a childish love of circuses and traveled the Bavarian countryside to escape his duties.

The family's homes were the Herzog-Max-Palais in Munich during winter and Possenhofen Castle in the summer months, far from the protocols of court.

She had four sisters: Helene, Marie Sophie, Mathilde and Sophie. And five brothers: Ludwig Wilhelm, Wilhelm Karl (dead with less than two months), Karl Theodor,Maximilian (born dead) and Maximilian

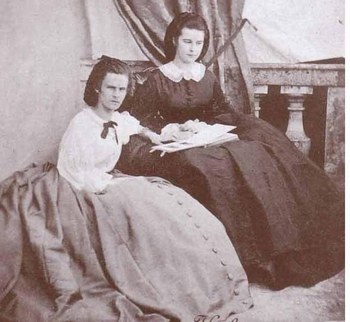

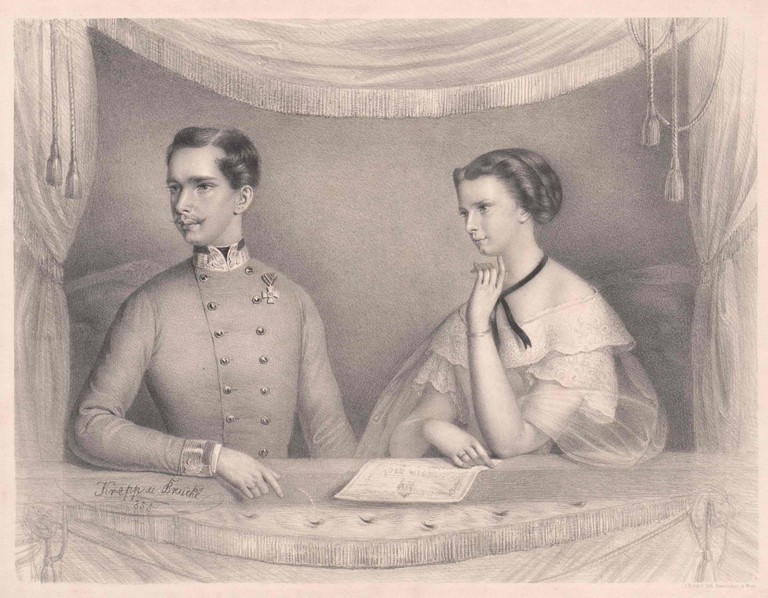

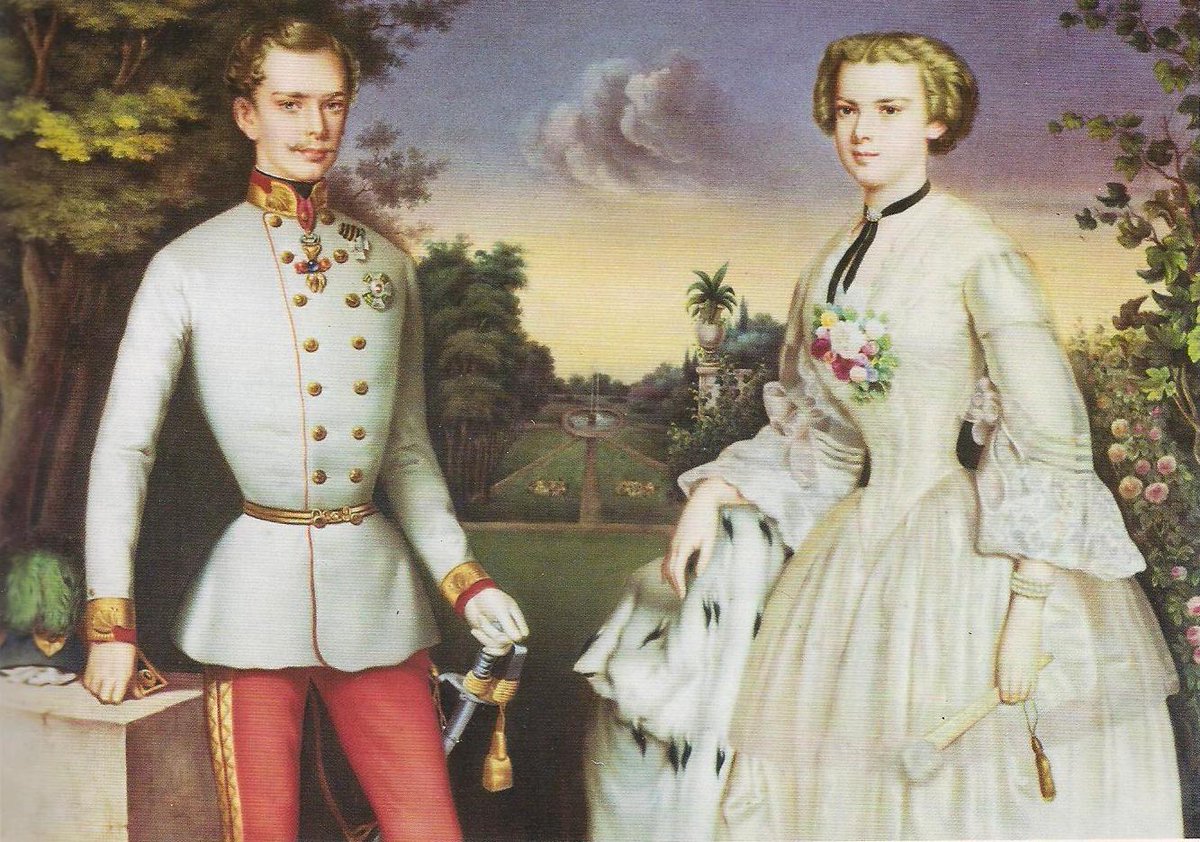

In 1853, Princess Sophie of Bavaria, the domineering mother of Emperor Franz Joseph, preferring to have a niece as a daughter-in-law rather than a stranger, arranged a marriage between her son and her sister Ludovika's eldest daughter, Helene ("Néné").

Although the couple had never met, Franz Joseph's obedience was taken for granted by the archduchess, who was once described as "the only man in the Hofburg" for her authoritarian manners.

The Duchess and Helene were invited to journey to the resort of Bad Ischl, Upper Austria to receive his formal proposal of marriage. Fifteen-year-old Sisi accompanied her mother and sister and they traveled from Munich.

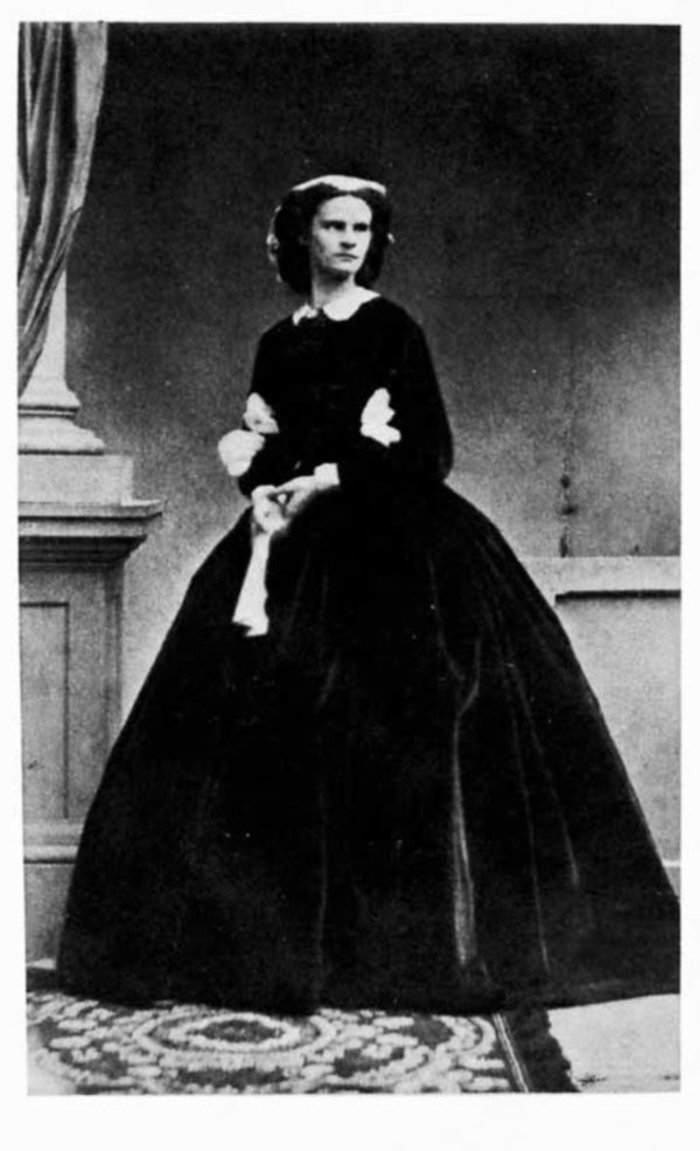

The family was still in mourning over the death of an aunt so they were dressed in black and unable to change to more suitable clothing before meeting the young Emperor.

Helene was a pious, quiet young woman, and she and Franz Joseph felt ill at ease in each other's company, but he was instantly infatuated with her younger sister.

He did not propose to Helene, but defied his mother and informed her that if he could not have Elisabeth, he would not marry at all. Five days later their betrothal was officially announced.

The couple were married eight months later in Vienna at the Augustinerkirche on 24 April 1854. The marriage was finally consummated three days later, and Elisabeth received a dower equal to US $240,000 today.

After enjoying an informal and unstructured childhood, Elisabeth, who was shy and introverted by nature, and more so among the stifling formality of Habsburg court life, had difficulty adapting to the Hofburg and its rigid protocols and strict etiquette.

She was surprised to find she was pregnant and gave birth to her first child, a daughter, Archduchess Sophie of Austria just ten months after her wedding.

Archduchess Sophie, who often referred to Elisabeth as a "silly young mother", not only named the child (after herself) without consulting the mother, but took complete charge of the baby, refusing to allow Elisabeth to breastfeed or otherwise care for her own child.

When a second daughter, Archduchess Gisela of Austria, was born a year later, the Archduchess Sophie took the baby away from Elisabeth as well.

She also was accused of having too much influence on her husband regarding his Italian and Hungarian subjects. When she traveled to Italy with him she persuaded him to show mercy toward political prisoners.

In 1857 Elisabeth visited Hungary for the first time with her husband and two daughters, and it left a deep and lasting impression upon her, probably because in Hungary she found a welcome respite from the constraints of Austrian court life.

Unlike the archduchess, who despised the Hungarians, Elisabeth felt such an affinity for them that she began to learn Hungarian; the country reciprocated in its adoration of her.

This same trip proved tragic as both of Elisabeth's children became ill. While Gisela recovered quickly, two-year-old Sophie grew steadily weaker, then died. It is generally assumed today that she died of typhus.

Her death pushed Elisabeth, who was already prone to bouts of melancholy, into periods of heavy depression, which would haunt her for the rest of her life.

She turned away from her living daughter, began neglecting her, and their relationship never recovered.

In December 1857 Elisabeth became pregnant for the third time in as many years, and her mother, who had been concerned about her daughter's physical and mental health, hoped that this new pregnancy would help her recover.

At 172 cm (5 feet 8 inches), Elisabeth was unusually tall. Even after three pregnancies she maintained her weight at approximately 50 kg (110 pounds, 7 st 12 lbs) for the rest of her life. She achieved this through fasting and exercise, such as gymnastics and riding.

In deep mourning after her daughter Sophie's death, Elisabeth refused to eat for days; a behavior that would reappear in later periods of melancholy and depression.

Whenever her weight threatened to exceed fifty kilos, a "fasting cure" or "hunger cure" would follow, which involved almost complete fasting

Meat itself often filled her with disgust, so she either had the juice of half-raw beefsteaks squeezed into a thin soup, or else adhered to a diet of milk and eggs.

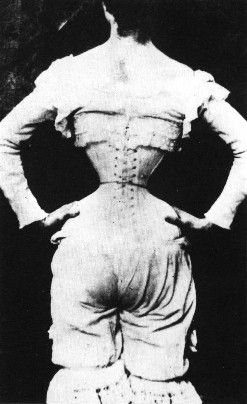

Elisabeth emphasised her extreme slenderness through the practice of "tight-lacing". During the peak period of 1859–60, which coincided with Franz-Joseph's political and military defeats in Italy, her sexual withdrawal from her husband after three pregnancies in rapid succession

and her losing battle with her mother-in-law for dominance in rearing her children, she reduced her waist to 40 cm (16 inches) in circumference.

Elisabeth's defiant flaunting of this exaggerated dimension angered her mother-in-law, who expected her to be pregnant continuously

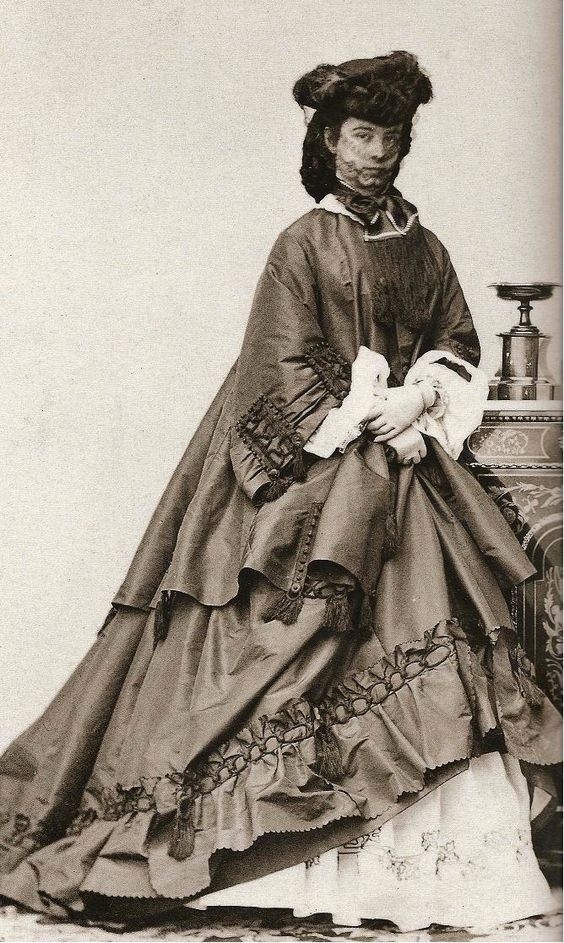

In her youth Elisabeth followed the fashions of the age, which for many years were cage-crinolined hoop skirts, but when fashion began to change, she was at the forefront of abandoning the hoop skirt for a tighter and leaner silhouette.

She never wore petticoats or any other "underlinen", as they added bulk, and was often literally sewn into her clothes, to bypass waistbands, creases, and wrinkles and to further emphasize the "wasp waist" that became her hallmark.

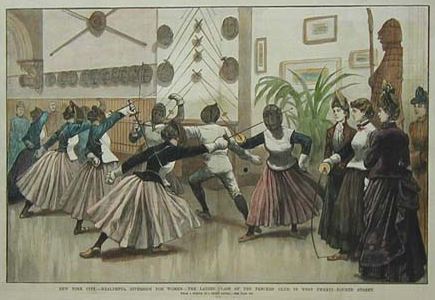

The empress developed extremely rigorous and disciplined exercise habits. Every castle she lived in was equipped with a gymnasium, the Knights' Hall of the Hofburg was converted into one.

Mats and balance beams were installed in her bedchamber so that she could practise on them each morning

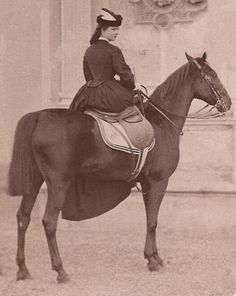

She took up fencing with equal discipline. A fervent horsewoman, she rode every day for hours on end, becoming probably the world's best, as well as best-known, female equestrian at the time.

When, due to sciatica, she could no longer endure long hours in the saddle, she substituted walking, subjecting her attendants to interminable marches and hiking tours in all weather.

In the last years of her life, Elisabeth became even more restless and obsessive, weighing herself up to three times a day. She regularly took steam baths to prevent weight gain; by 1894 she had wasted away to near emaciation, reaching her lowest point of 95.7 lbs (43.5 kg).

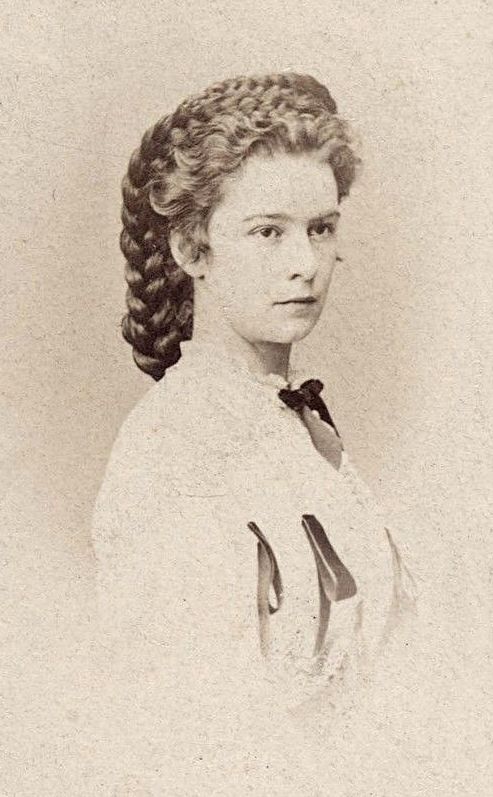

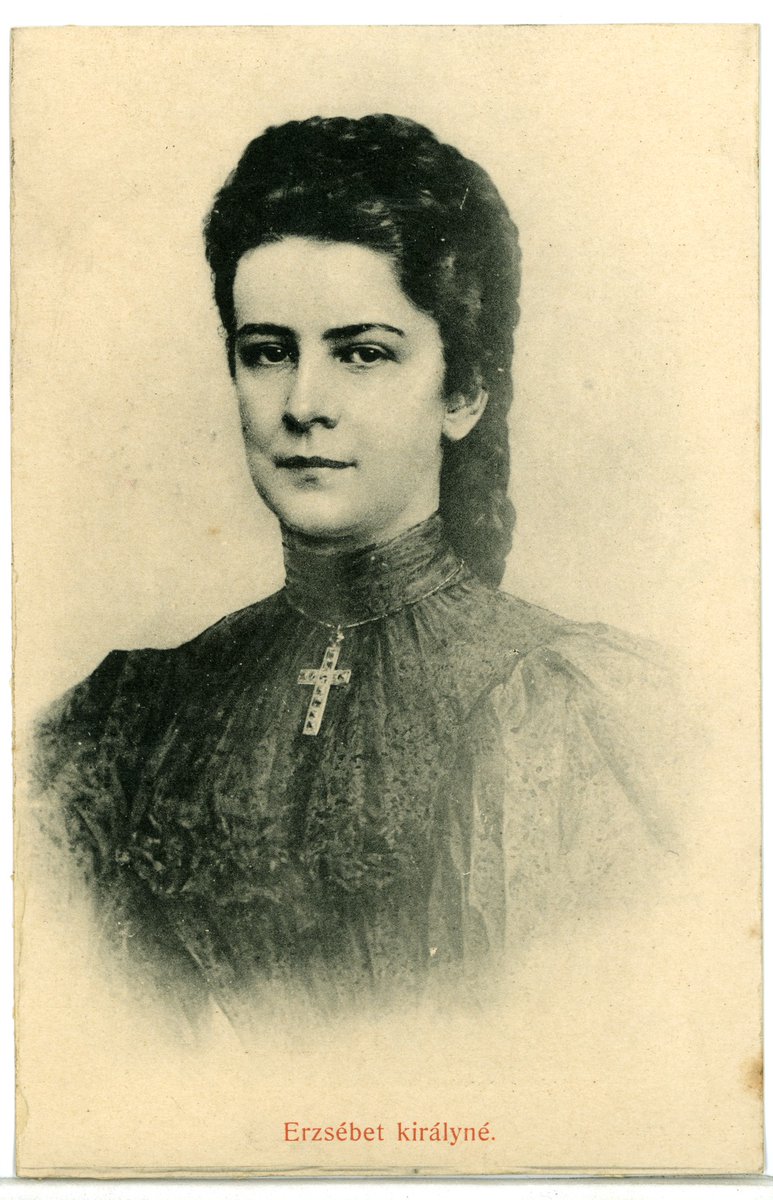

In addition to her rigorous exercise regimen, Elisabeth practiced demanding beauty routines. Daily care of her abundant and extremely long hair, which in time turned from the dark blonde of her youth to chestnut brunette, took at least three hours.

Her hair was so long and heavy that she often complained that the weight of the elaborate double braids and pins gave her headaches. Her hairdresser, Franziska Feifalik, was originally a stage hairdresser at the Wiener Burgtheater.

Responsible for all of Elisabeth's ornate hairstyles, she generally accompanied her on her wanderings. Feifalik was forbidden to wear rings and required to wear white gloves.

After hours of dressing, braiding, and pinning up the Empress' tresses, the hairs that fell out had to be presented in a silver bowl to her reproachful empress for inspection.

When her hair was washed with a combination of eggs and cognac once every two weeks, all activities and obligations were cancelled for that day.

Elisabeth used these captive hours during grooming to learn languages; she spoke fluent English and French, and added modern Greek to her Hungarian studies.

Her night and bedtime rituals were just as demanding. Elisabeth slept without a pillow on a metal bedstead, which she believed was better for retaining and maintaining her upright posture; either raw veal or crushed strawberries lined her nightly leather facial mask

She was also heavily massaged, and often slept with cloths soaked in either violet- or cider-vinegar above her hips to preserve her slim waist; her neck was wrapped with cloths soaked in Kummerfeld-toned washing water

To further preserve her skin tone, she took both a cold shower every morning (which in later years aggravated her arthritis) and an olive-oil bath in the evening.

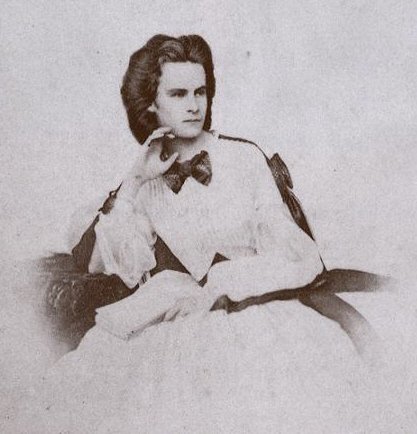

After age thirty-two, she decided she did not want the public image of the eternal beauty challenged. Therefore, she did not sit for any more portraits, and would not allow any photographs.

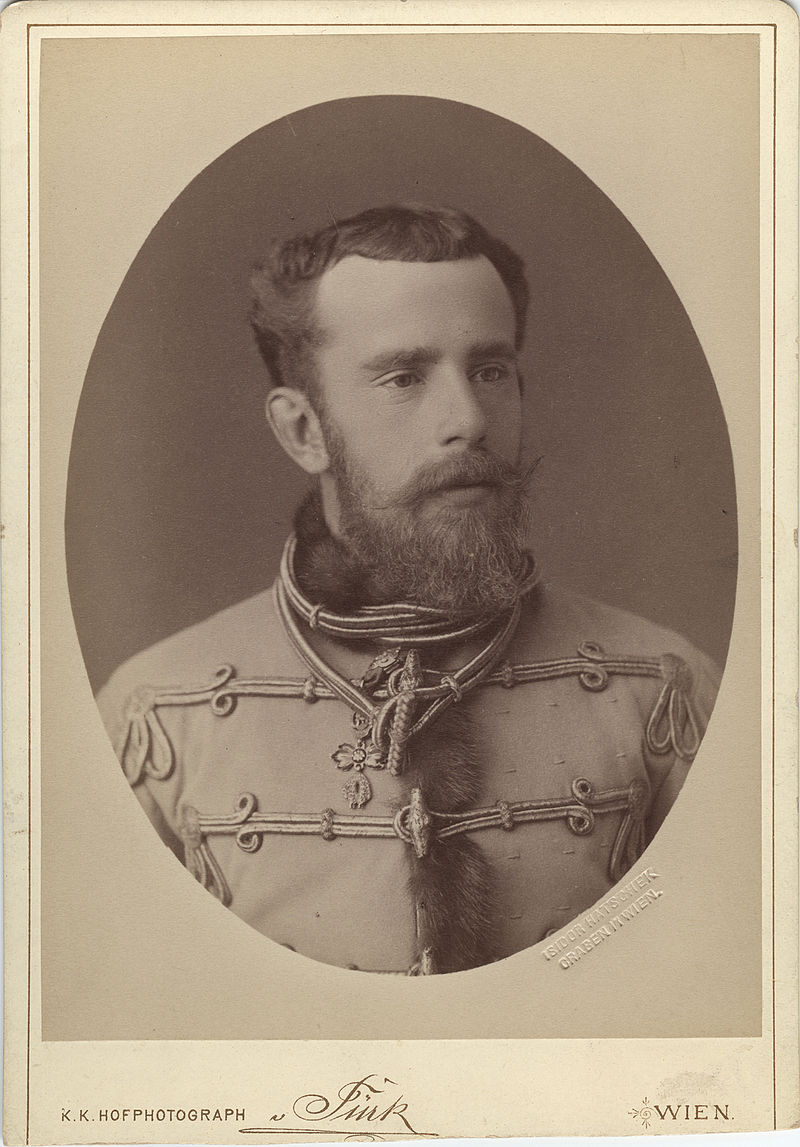

Franz Joseph was passionately in love with his wife, but she did not reciprocate his feelings fully and felt increasingly stifled by the rigidness of court life. He was a very sober man.

Restless to the point of hyperactivity, naturally introverted, and emotionally distant from her husband, she fled him as well as her duties of life at court, avoiding them both as much as she could.

He indulged her wanderings, but constantly and unsuccessfully tried to tempt her into a more domestic life with him.

Elisabeth slept very little and spent hours reading and writing at night, and even took up smoking, a shocking habit for women which made her the further subject of already avid gossip.

She had a special interest in history, philosophy, and literature, and developed a profound reverence for the German lyric poet and radical political thinker, Heinrich Heine, whose letters she collected.

She tried to make a name for herself by writing Heine-inspired poetry. Referring to herself as Titania, Shakespeare's Fairy Queen, Elisabeth expressed her intimate thoughts and desires in a large number of romantic poems

which served as a type of secret diary. Most of her poetry relates to her journeys, classical Greek and romantic themes, and ironic commentary on the Habsburg dynasty.

On 21 August 1858, Elisabeth finally gave birth to an heir, Rudolf. The 101-gun salute announcing the welcome news to Vienna also signaled an increase in her influence at court.

Her interest in politics had developed as she matured; she was liberal-minded, and placed herself decisively on the Hungarian side in the increasing conflict of nationalities within the empire.

When Elisabeth was still blocked from controlling her son's upbringing and education, she openly rebelled. Due to her nervous attacks, fasting cures, severe exercise regime, and frequent fits of coughing, the state of her health had become really alarming.

During this time the court was rife with malicious rumors that Franz Joseph was having a liaison with an actress named Frau Roll,leading to speculation today that Elisabeth's symptoms could have been anything from psychosomatic to a result of venereal disease.

Elisabeth seized on the excuse and left her husband and children, to spend the winter in seclusion. Six months later, a mere four days after her return to Vienna, she again experienced coughing fits and fever.

She ate hardly anything and slept badly, and Dr. Skoda (a lung specialist) observed a recurrence of her lung disease. A fresh rest cure was advised, this time on Corfu, where she improved almost immediately.

In 1862 she had not seen Vienna for a year when her family physician, Dr. Fischer of Munich, examined her and observed serious anemia and signs of "dropsy" (edema). Her feet were sometimes so swollen that she could walk only laboriously, and with the support of others.

On medical advice, she went to Bad Kissingen for a cure. Elisabeth recovered quickly at the spa, and then she spent more time with her own family in Bavaria. In August 1862, after a two-year absence, she returned shortly before her husband's birthday.

Rudolf was now four years old, and Franz Joseph hoped for another son to safeguard the succession. Dr. Fischer claimed that the health of the empress would not permit another pregnancy.

Elisabeth fell into her old pattern of escaping boredom and dull court protocol through frequent walking and riding, using her health as an excuse to avoid both official obligations and sexual intimacy.

She was now more assertive in her defiance of her husband and mother-in-law than before, openly opposing them on the subject of the military education of Rudolf, who, like his mother, was extremely sensitive and not suited to the life at court.

After having used every excuse to avoid pregnancy, Elisabeth later decided that she wanted a fourth child.

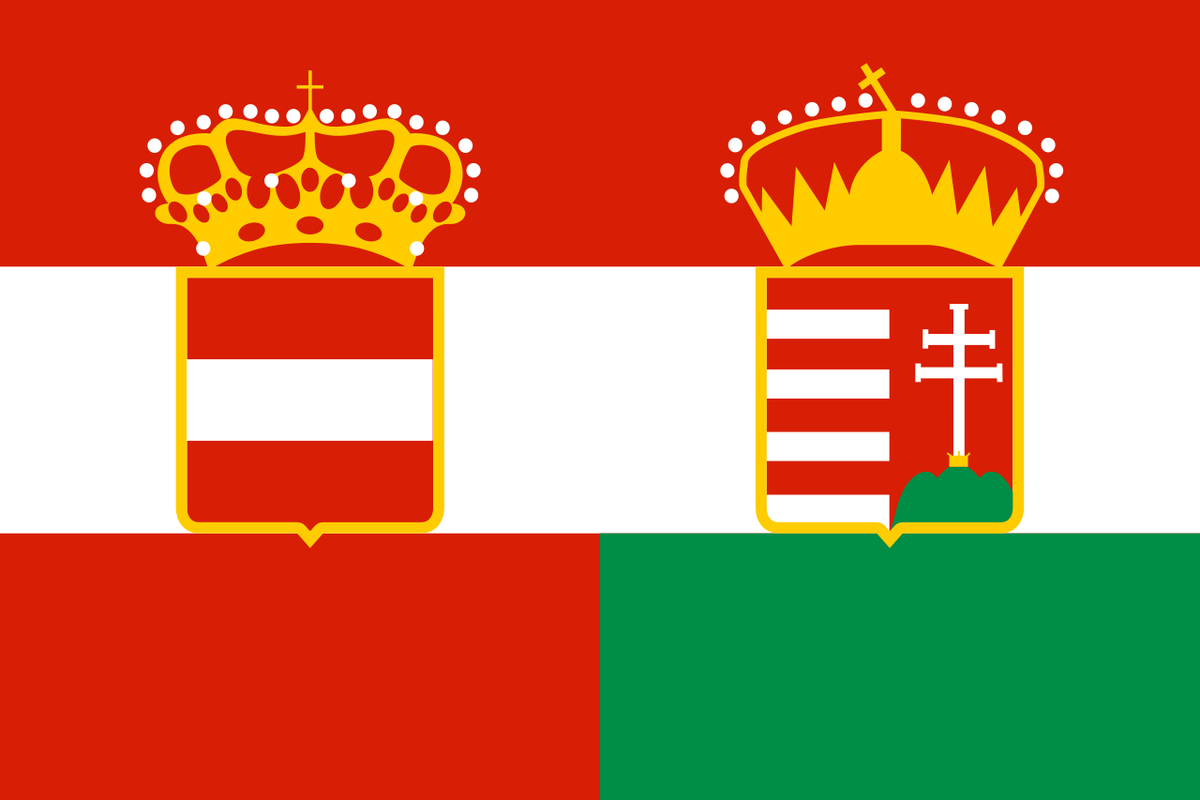

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 created the dual monarchy of Austria–Hungary. Gyula Andrássy was made the first Hungarian prime minister and in return, he saw that Franz Joseph and Elisabeth were officially crowned King and Queen of Hungary in June.

As a coronation gift, Hungary presented the royal couple with a country residence in Gödöllő, 32 kilometres (20 mi) east of Buda-Pest.

Later she gave birth to a daughter, Marie Valerie (1868–1924). Dubbed the "Hungarian child", she was born in Buda-Pest ten months after her parents' coronation and baptised there in April.

Determined to bring this last child up by herself, Elisabeth finally had her way. She poured all her repressed maternal feelings on her youngest daughter to the point of nearly smothering her. Sophie's influence over Elisabeth's children and the court faded, and she died in 1872.

Newspapers published articles on her passion for riding sports, diet and exercise regimens, and fashion sense. She often shopped at the Budapest fashion house, Antal Alter (now Alter és Kiss), which had become very popular with the fashion-crazed crowd.

To prevent him from becoming lonely during her long absences, Elisabeth encouraged her husband Franz Joseph's close relationship with actress Katharina Schratt.

On her journeys, Elisabeth sought to avoid all public attention and crowds of people. She was mostly travelling incognito, using pseudonyms like 'Countess of Hohenembs'. Elisabeth also refused to meet European monarchs when she did not feel like it.

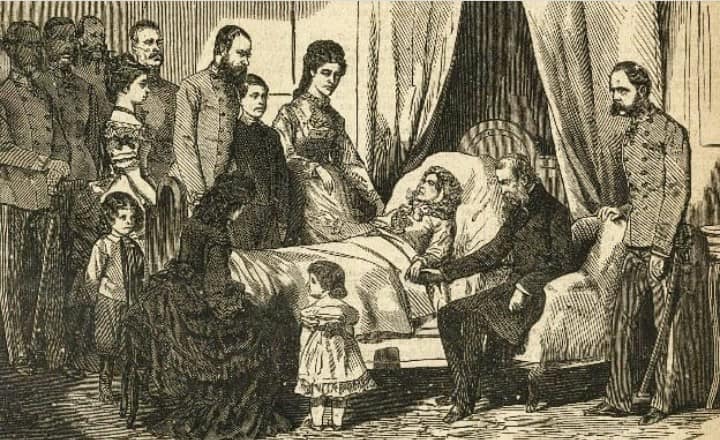

In 1889 Elisabeth's life was shattered by the death of her only son Rudolf, who was found dead together with his young lover Baroness Mary Vetsera, in what was suspected to be a murder-suicide on Rudolf's part.

The scandal was known as the Mayerling Incident after the location of Rudolf's hunting lodge in Lower Austria, where they were found.

Elisabeth never recovered from the tragedy, sinking further into melancholy. Within a few years, she had lost her father, Max Joseph (in 1888), her only son, Rudolf (1889), her sister Duchess Sophie in Bavaria (1897), Helene (1890) and her mother, Ludovika (1892).

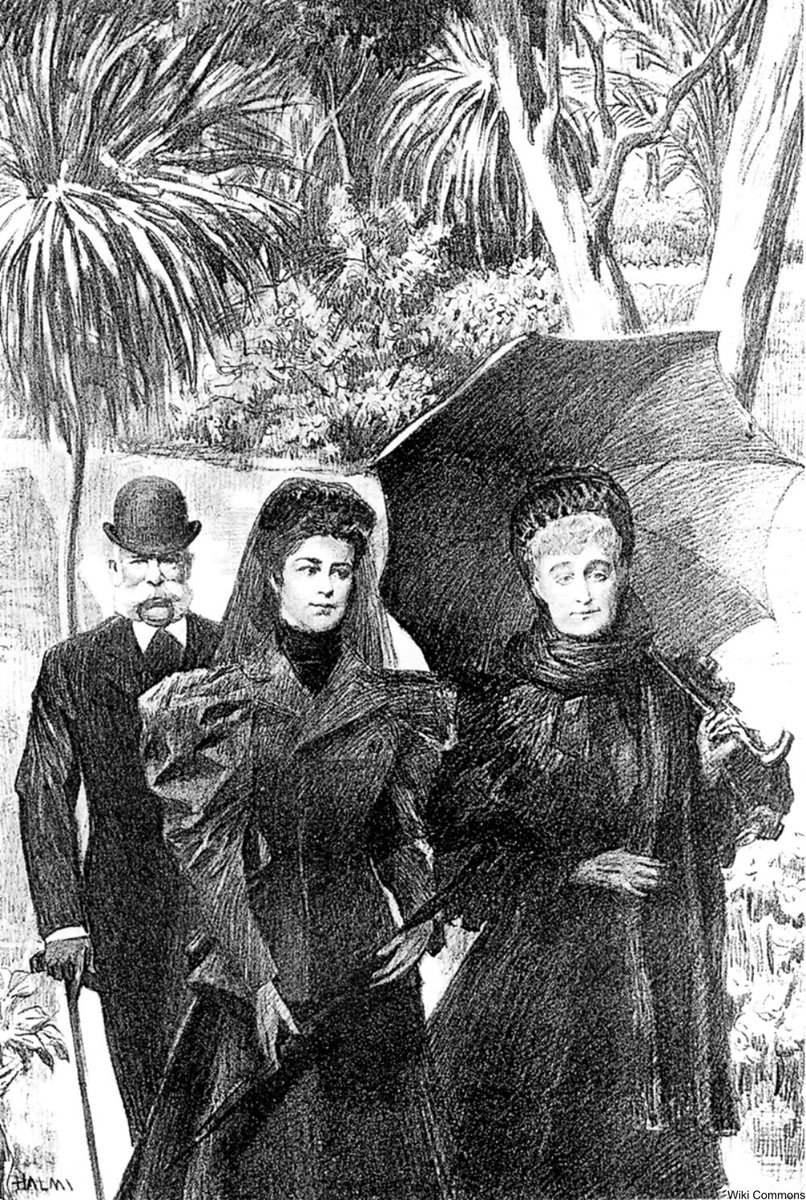

After Rudolf's death she was thought to have dressed only in black for the rest of her life. She wore long black dresses that could be buttoned up at the bottom, and carried a white parasol made of leather in addition to a concealing fan to hide her face from the curious.

Elisabeth spent little time in Vienna with her husband. Their correspondence increased during their last years, however, and their relationship became a warm friendship.

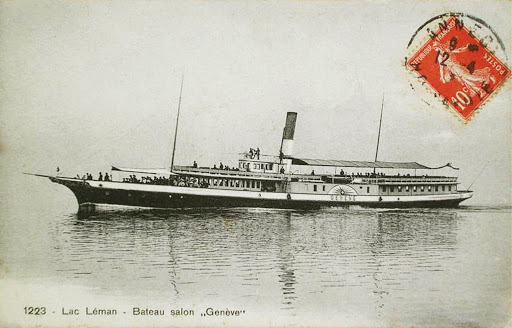

On her imperial steamer, Miramar, Empress Elisabeth travelled through the Mediterranean sea. Her favourite places were Cape Martin on the French Riviera, and also Sanremo on the Ligurian Riviera; Lake Geneva in Switzerland; Bad Ischl in Austria, and Corfu.

After her son's death, she commissioned the building of a palace on the Island of Corfu which she named the Achilleion, after Homer's hero Achilles in The Iliad.

Emperor Franz Joseph I was hoping that his wife would finally settle down in her palace Achilleion on Corfu, but Sisi soon lost interest in the fairytale property. The endless travels became a means of escape for Elisabeth from her life and her misery.

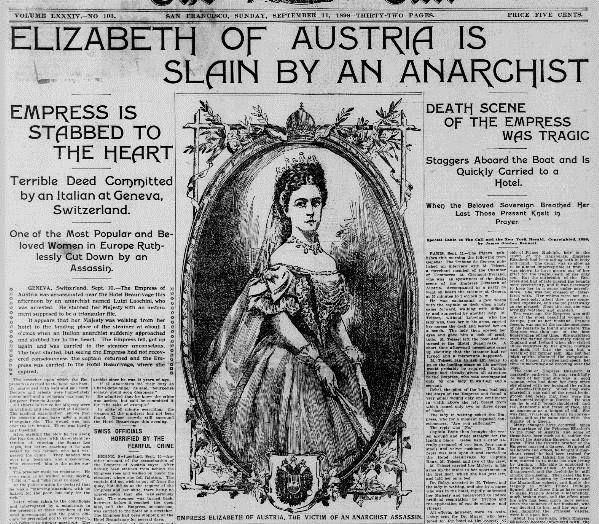

In 1898, despite warnings of possible assassination attempts, the 60-year-old Elisabeth traveled incognito to Geneva, Switzerland. However, someone from the Hôtel Beau-Rivage revealed that the Empress of Austria was their guest.

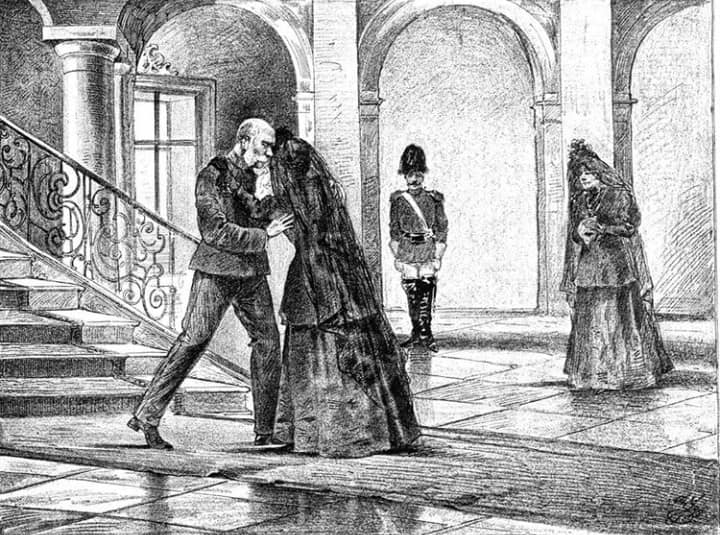

At 1:35 p.m. on Saturday 10 September 1898, Elisabeth and Countess Irma Sztáray de Sztára et Nagymihály, her lady-in-waiting, left the hotel on the shore of Lake Geneva on foot to catch the steamship Genève for Montreux.

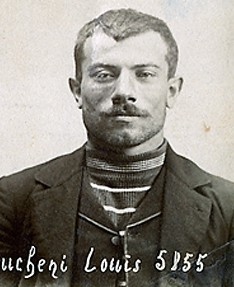

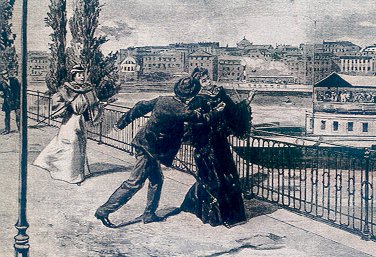

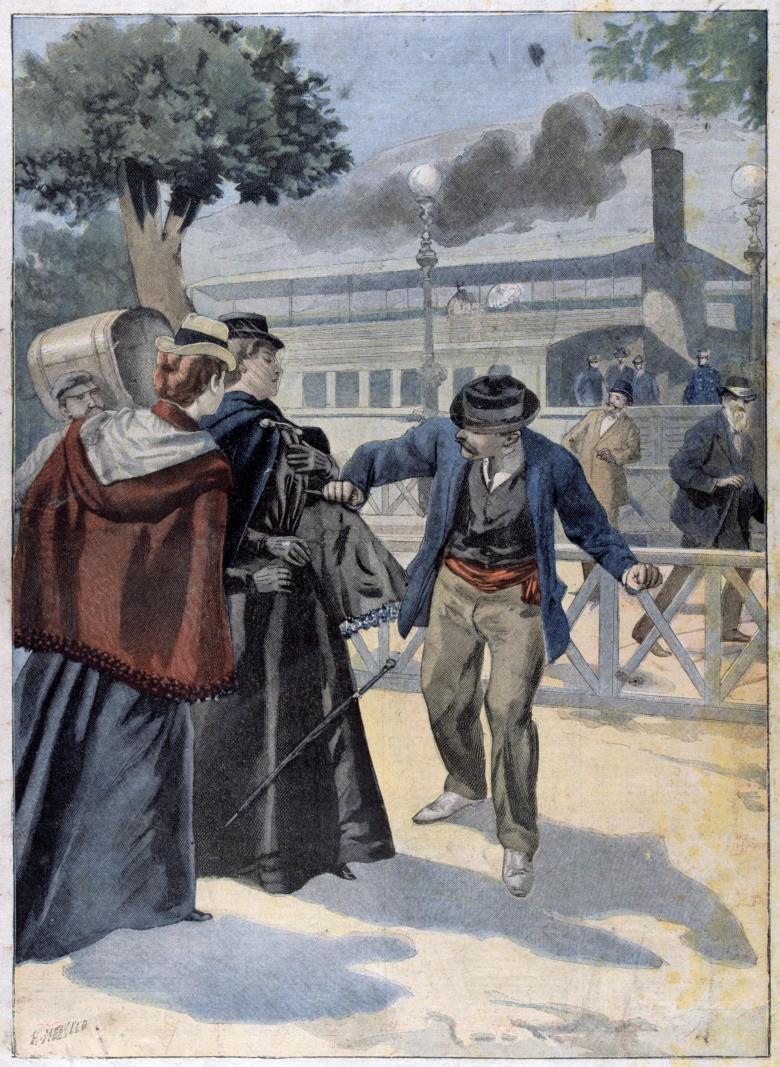

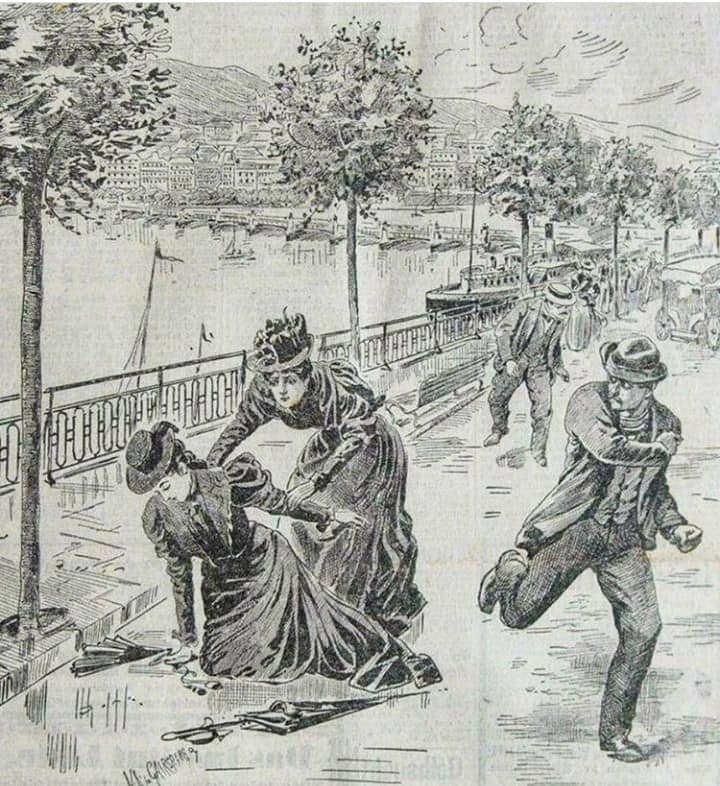

They were walking along the promenade when the 25-year-old Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni approached them, attempting to peer underneath the empress's parasol.

According to Sztáray, as the ship's bell announced the departure, Lucheni seemed to stumble and made a movement with his hand as if he wanted to maintain his balance.

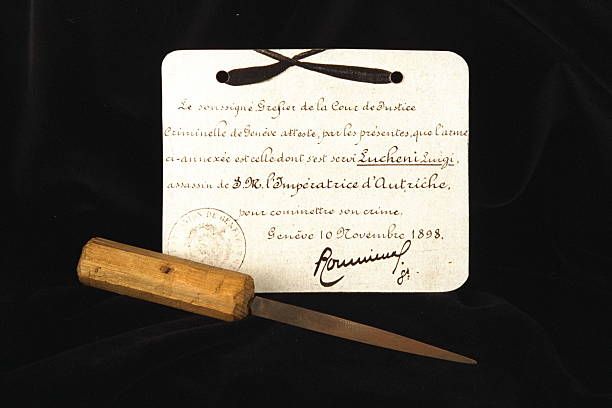

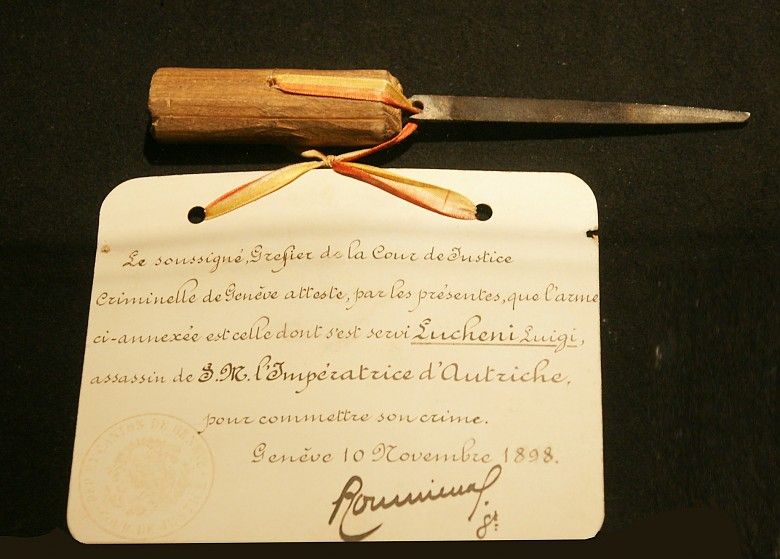

He stabbed Elisabeth with a sharpened needle file that was 4 inches (100 mm) long (used to file the eyes of industrial needles) that he had inserted into a wooden handle

Lucheni originally planned to kill the Duke of Orléans; but the Pretender to France's throne had left Geneva earlier for the Valais.

Failing to find him, the assassin selected Elisabeth when a Geneva newspaper revealed that the elegant woman traveling under the pseudonym of "Countess of Hohenembs" was the Empress Elisabeth of Austria

After Lucheni struck her, the empress collapsed. A coach driver helped her to her feet and alerted the Austrian concierge of the Beau-Rivage, a man named Planner, who had been watching the empress's progress toward the Genève.

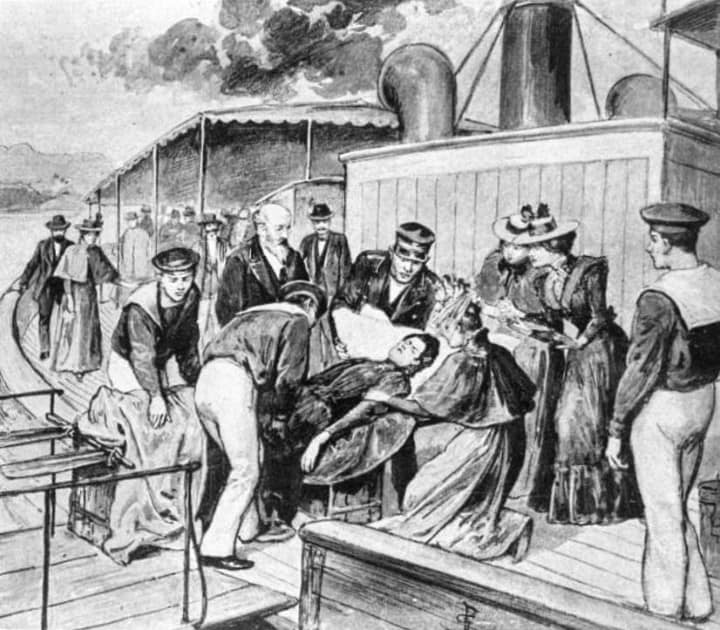

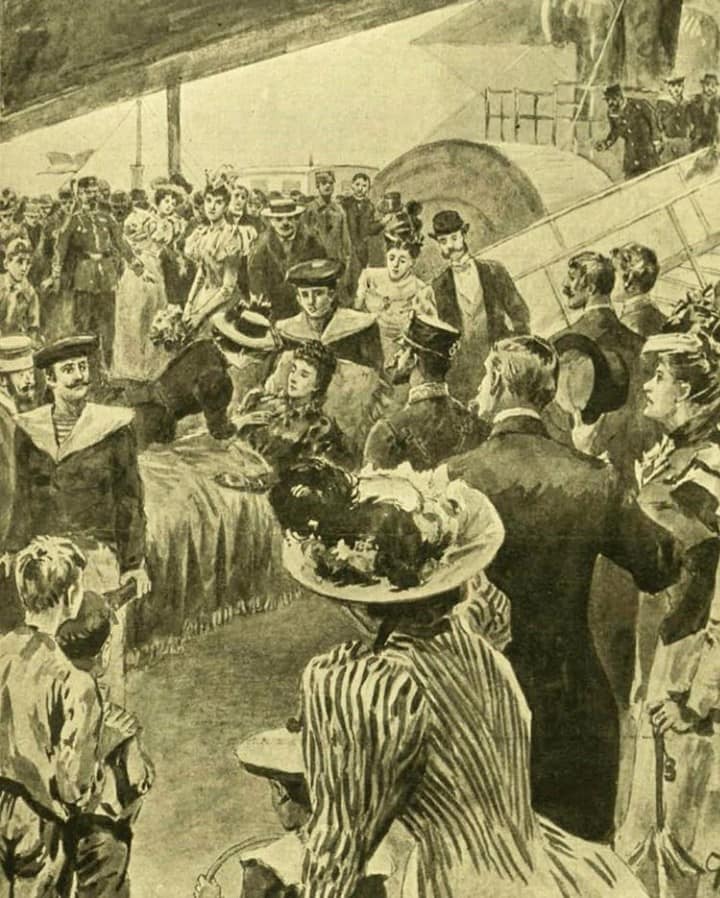

The two women walked roughly 100 yards (91 m) to the gangway and boarded, at which point Sztáray relaxed her hold on Elisabeth's arm. The empress then lost consciousness and collapsed next to her.

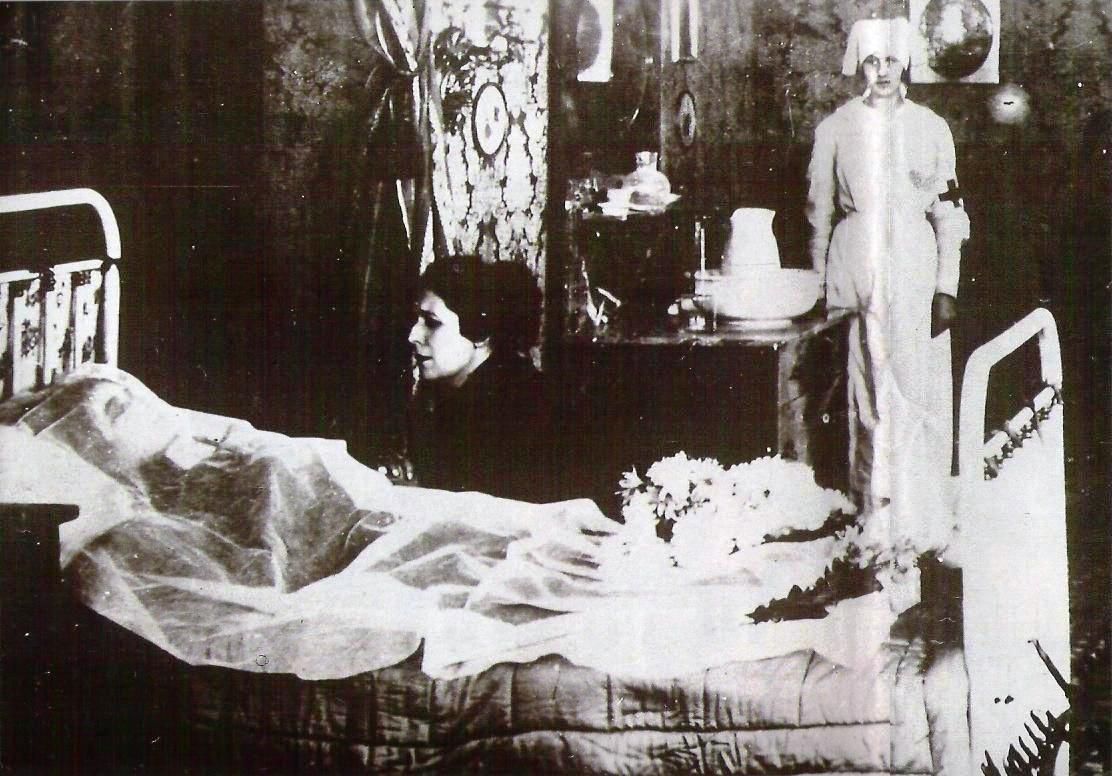

Sztáray called for a doctor, but only a former nurse, a fellow passenger, was available. Three men carried Elisabeth to the top deck and laid her on a bench. Sztáray opened her dress, cut Elisabeth's corset laces so she could breathe.

Elisabeth revived somewhat and Sztáray asked her if she was in pain, and she replied, "No". She then asked, "What has happened?”and lost consciousness again.

Countess Sztáray noticed a small brown stain above the empress's left breast. Alarmed that Elisabeth had not recovered consciousness, she informed the captain of her identity, and the boat turned back to Geneva.

Elisabeth was carried back to the Hotel Beau-Rivage by six sailors on a stretcher improvised from a sail, cushions and two oars. Fanny Mayer, the wife of the hotel director, a visiting nurse, and the countess undressed Elisabeth.

Two doctors, Dr. Golay and Dr. Mayer arrived, along with a priest, who was too late to grant her absolution. Mayer incised the artery of her left arm to ascertain death, and found no blood.

She was pronounced dead at 2:10 p.m. Everyone knelt down and prayed for the repose of her soul, and Countess Sztáray closed Elisabeth's eyes and joined her hands. Elisabeth had been the Empress of Austria for 44 years.

When Franz Joseph received the telegram informing him of Elisabeth's death, his first fear was that she had committed suicide. It was only when a later message arrived, detailing the assassination, that he was relieved of that notion.

The autopsy was performed the next day by Golay, who discovered that the weapon, had penetrated 3.33 inches (85 mm) into Elisabeth's thorax, fractured the fourth rib, pierced the lung and pericardium,

and penetrated the heart from the top before coming out the base of the left ventricle. Because of the sharpness and thinness of the file the wound was very narrow and, due to pressure from Elisabeth's extremely tight corseting,

the hemorrhage of blood into the pericardial sac around the heart was slowed to mere drops. Until this sac filled, the beating of her heart was not impeded, which is why Elisabeth had been able to walk from the site of the assault and up the boat's boarding ramp.

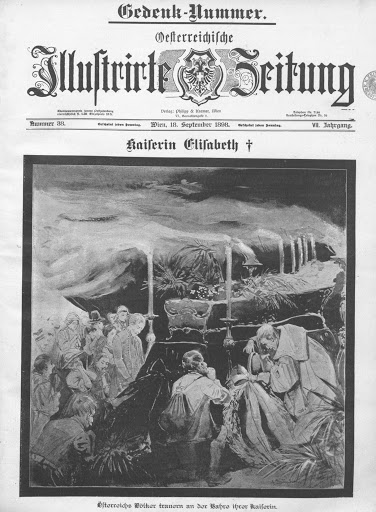

Elisabeth's body was placed in a triple coffin: two inner ones of lead, the third exterior one in bronze, reposing on lion claws. On Tuesday, before the coffins were sealed, Franz Joseph's official representatives arrived to identify the body.

The coffin was fitted with two glass panels, covered with doors, which could be slid back to allow her face to be seen.

On Wednesday morning, Elisabeth's body was carried back to Vienna aboard a funeral train. The inscription on her coffin read, “Elisabeth, Empress of Austria”. The Hungarians were outraged and the words, “and Queen of Hungary” were hastily added.

The entire Austro-Hungarian Empire was in deep mourning; 82 sovereigns and high-ranking nobles followed her funeral cortege on the morning of 17 September to the tomb in the Capuchin Church.

The End

The End

Thank you very much If you read until the end! I know this has been incredibly long, but she is such a special person to this account that I didn't want to leave anything out!

Kisses on the forehead for everyone who's reading this

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter