Early yesterday morning we said goodbye to my father, Robert Murphy. I would like to say a few things about him here.

Robert was born Robert Clark Shannon on the 10th February 1944, the first child of Jessie Shannon. Her address was 30 John Knox Street, in Townhead in the East End of Glasgow, near the Cathedral and the Necropolis.

Jessie was 19 years old, her occupation listed as “engine waste machinist”, presumably a wartime job. No father was listed on the birth certificate.

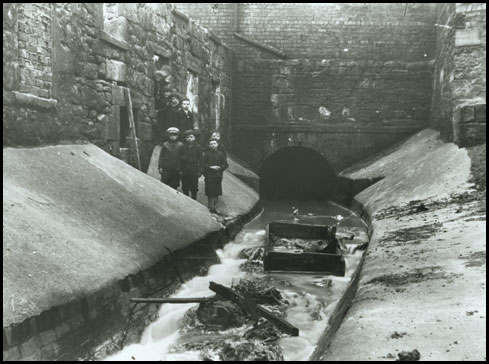

Looking at a map of the time, the tenement where they lived was opposite Glasgow’s infamous Duke Street Prison, and backed onto a “Skin and Wool Works”, the uncovered Molendinar Burn, and the Wellpark Brewery, where Tennant’s Lager is still manufactured.

One of Robert’s brothers remembers them playing in the skin factory, leaping into huge piles of wool, and mucking around in the Molendinar, which was often filled with raw sewage emptied out by the Royal Infirmary up the hill.

Robert was for a while known as Robert Brooks, and an Albert Brooks, “ship stoker” would later be listed as his father on his wedding certificate. By the time he was seven he had been joined by a brother, Albert, and a sister Elizabeth.

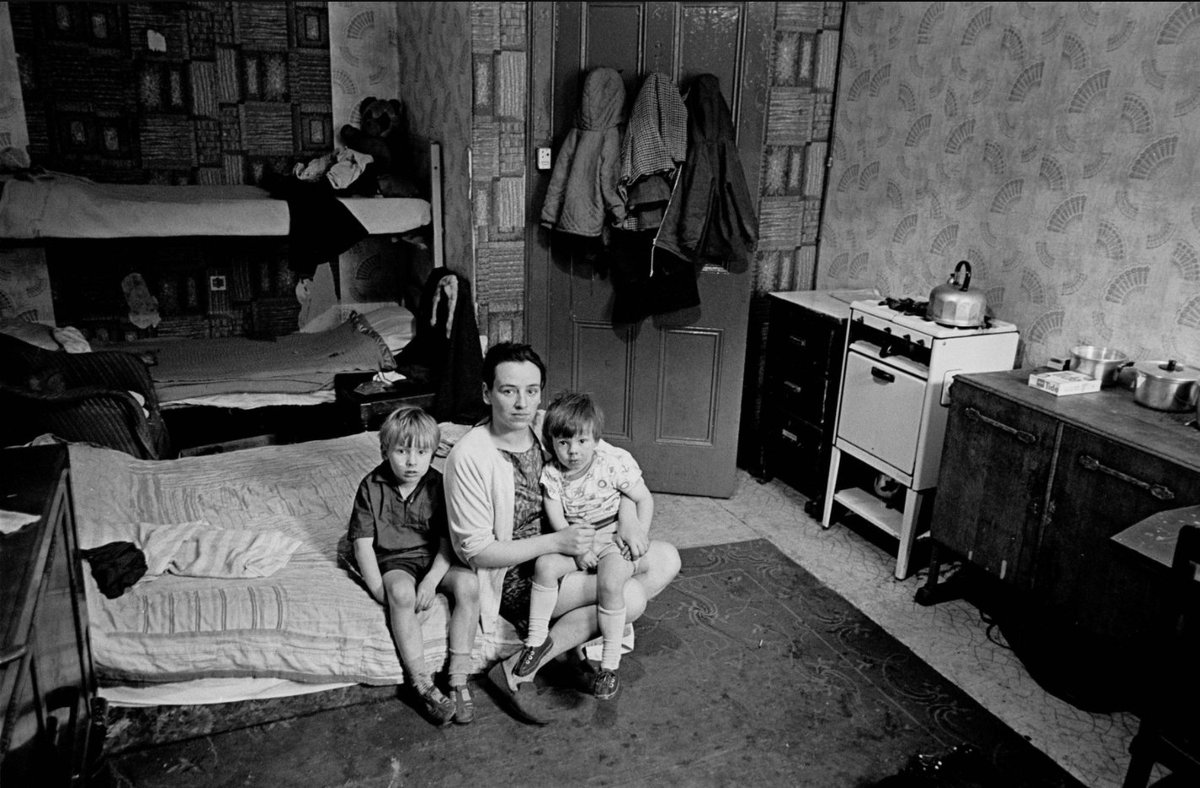

Soon, though, Jessie was in a relationship with Patrick Kevin Murphy, and the family started to grow quickly. By the time he was sixteen years old, Robert had ten siblings, and they were all still crammed into the flat off Duke Street.

Eventually Robert would be the eldest of sixteen siblings, not including one child, Jim, informally adopted into the family for good measure. Robert was born in 1944, his youngest brother, Patrick, in 1968.

Jessie’s near constant pregnancy can be attributed to the attitudes and teachings of the Roman Catholic Church, and Robert would always have a strained relationship with his stepfather. For this and perhaps other reasons, he emphatically rejected religion early on in his life.

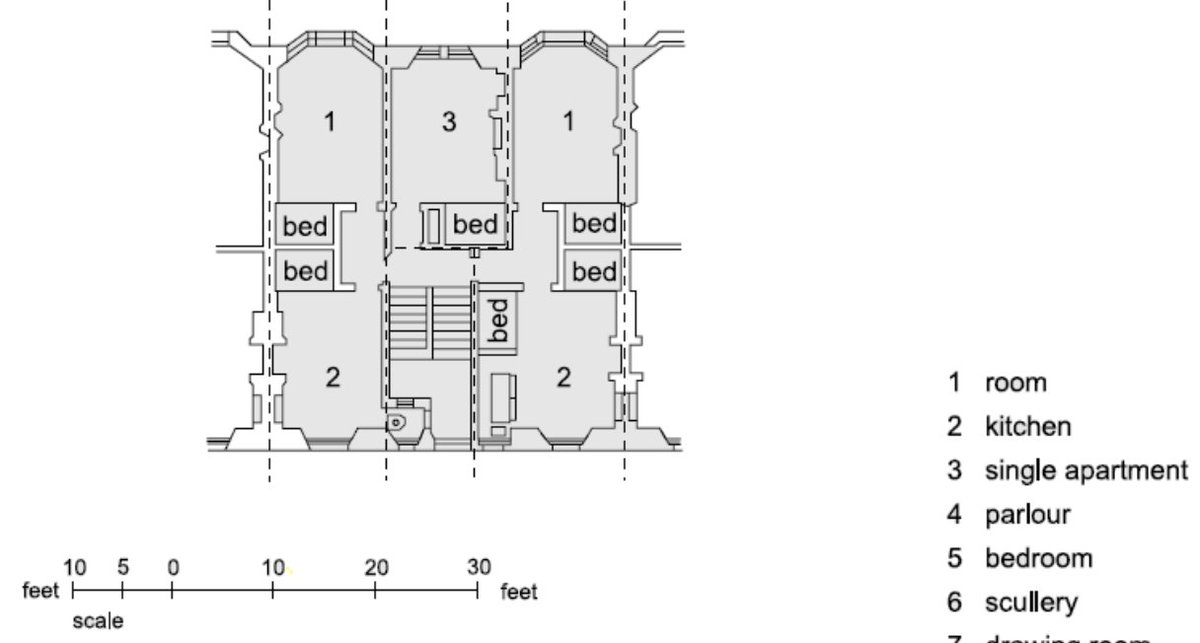

The Murphys lived in one of Glasgow’s legendary ‘Single Ends’ – a one-room flat, probably no more than 16 sq.m, with a single toilet shared between multiple dwellings. It would have a box bed in an alcove, but mattresses would be spread across the floor at night.

Robert, as the eldest, was vital to the running of the family, and various of his siblings talk of his role in their childcare. He was already showing promise at school, encouraged by his mother, whose own talents had been thwarted.

Eventually the family got a council house, and they moved north to Springburn, to a flat in a 1930s tenement in Drumbottie Road. By now Robert was referring to himself as Murphy.

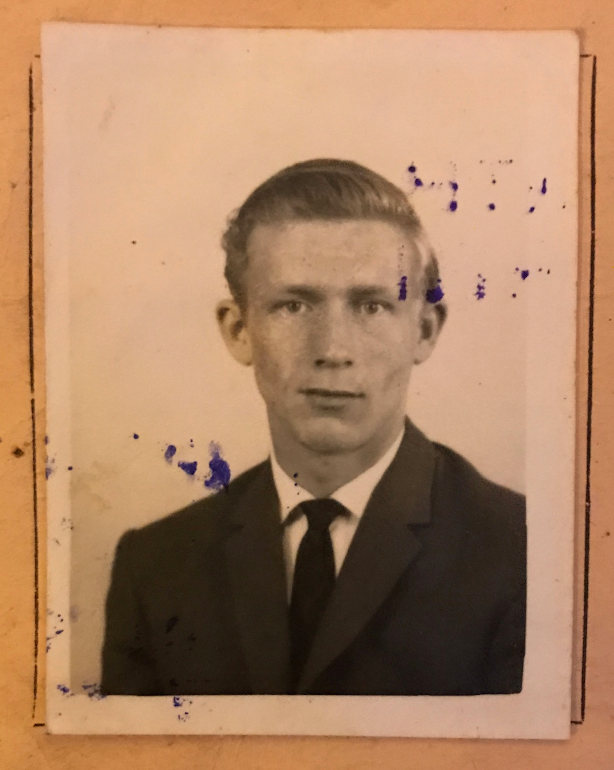

Robert had done well enough at school to apply for university, but he deferred, spending a year working as variously a nighttime security guard at a factory and behind the desk at the unemployment office, to save up the money to buy a jacket for his interview.

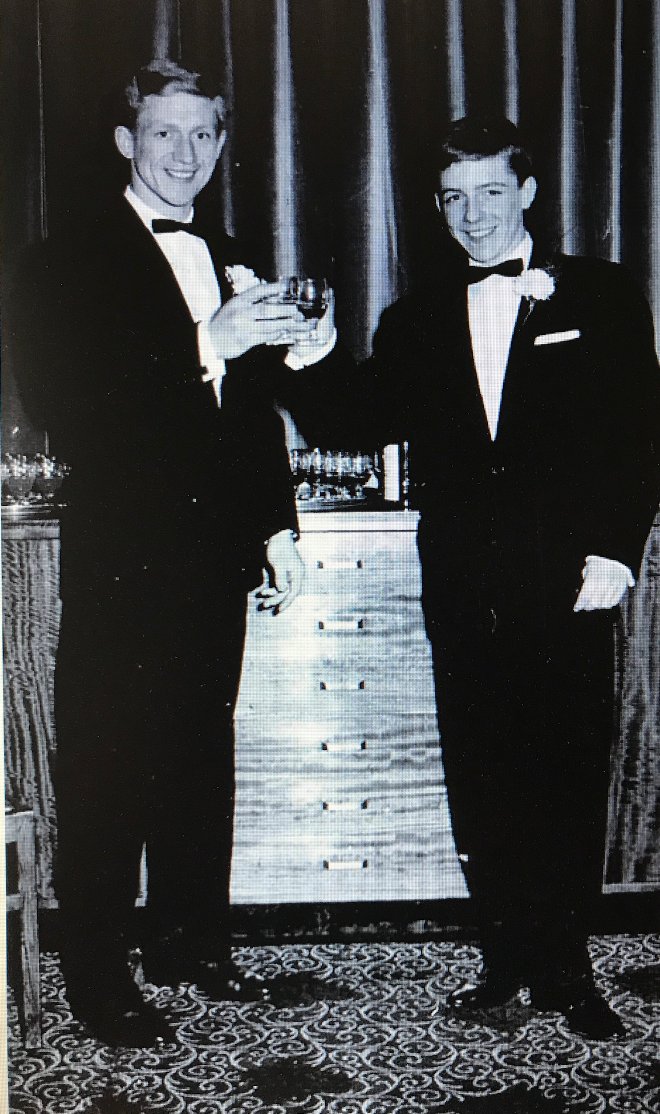

He attended Glasgow University from 1963-66, studying maths and physics, as well as botany. Glasgow Uni was undergoing an expansion around the findings of the Robbins Report, and rebuilding its campus in Hillhead, a time of great change and optimism.

But things weren’t easy. Robert remembered each day having to choose between taking the bus and having the money to buy lunch. He would remain the only one of his siblings to receive a higher education.

Upon graduation, and considering his options, Robert decided to train to become a teacher and entered Jordanhill College for his professional qualification. He entered the profession as a maths teacher at the end of the 1960s.

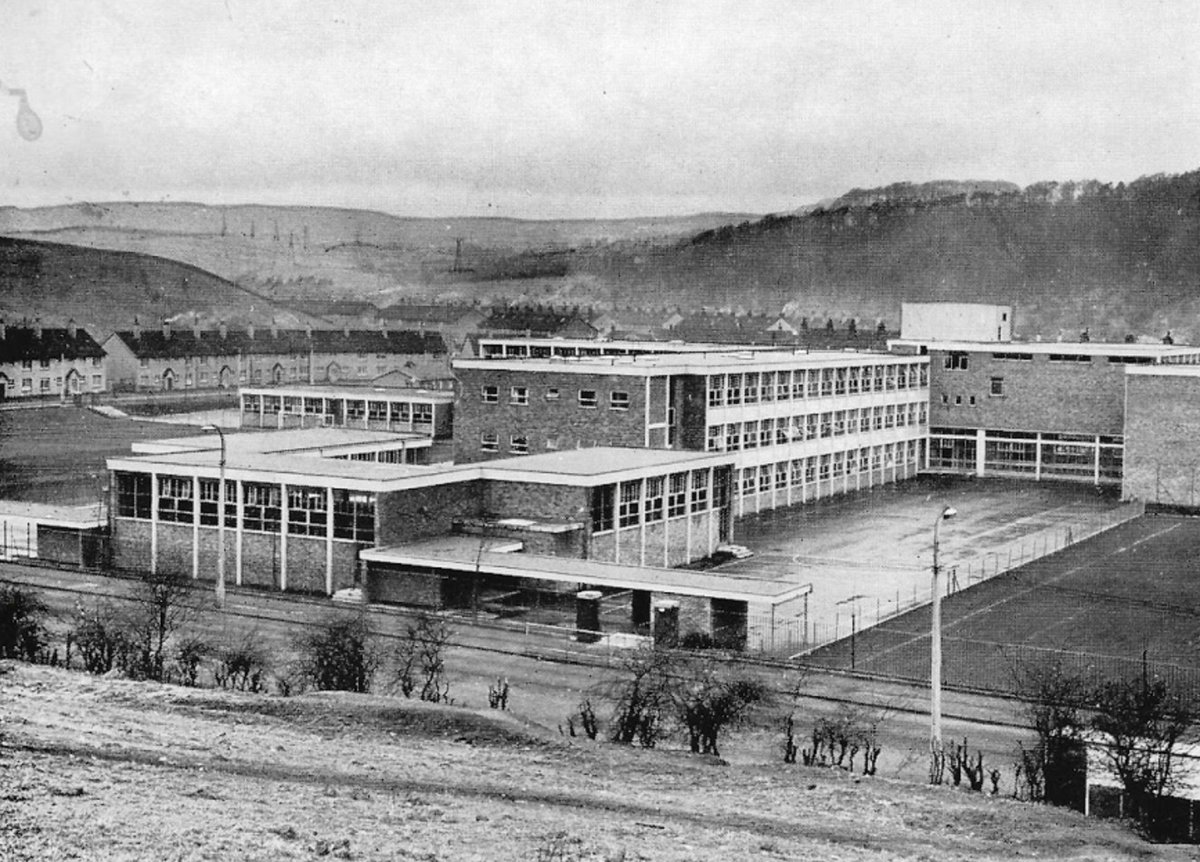

When he started teaching, his places of work were often brand new modern buildings, such as Kings Park, designed by Gillespie Kidd and Coia. The post-war reconstruction was in full swing.

At that point, teaching was considered a much more respectable job than it is now, and later Robert would lament the gradual, relentless decline of working conditions and authority, especially once Thatcherism took hold.

After a few years, Robert was able to put down a deposit for a flat in Kelvindale, a semi-suburban area at the outer fringe of Glasgow’s West End, a name that suggested affluence compared to Townhead or Springburn.

By the mid-70s he was working at Waverley School in Drumchapel, a modern school in a Glasgow ‘scheme’, a new overspill neighbourhood to the west of the city, which swiftly came to suffer increasing social problems.

At Waverley, Robert met Wilma Cuthill, who was teaching English. When they began dating, Wilma’s mother was very ill with cancer, and Robert would come to meet Wilma after she had been visiting the hospital, and keep her company in those difficult times.

Wilma and Robert were married on the 28th December 1976, and over the next 7 years had two children, Kathryn ( @manymanyplies) and Douglas. The family moved to a semi-detached house nearby in Kelvindale.

Robert’s career peaked as principle teacher of maths at Hyndland Secondary School, but teaching was grinding him down. The conditions of work, not to mention the stresses of dealing with unruly and uninterested pupils, wore him out.

Gradually he came to hate the job, and as part of a general cuts package, he would accept an early retirement deal in the late 1990s, which changed his life significantly for the better.

Health had always been a problem for Robert. The straightened conditions of his youth left him weak, with perennial lung problems, possibly stemming from childhood tuberculosis. It’s also probable that years of chalk dust exposure in school contributed to these issues.

But he fought against these constraints, and lived an incredibly active life. He was an avid mountaineer, a skilled rock climber, a trained kayaking instructor, and a long distance runner, achieving an impressive 3h16m at the Glasgow Marathon in 1984, aged 40.

As someone for whom education had been his opportunity to escape poverty, knowledge was incredibly important to him. He had interests in birdwatching, astronomy, geology and botany, while crosswords, quizzes and other puzzles were a constant occupation of his leisure time.

He was also an incredibly skilled maker. An accomplished carpenter, he built much of the furniture in his house, and after retirement worked for a time renovating the flats of friends.

He built toys for his children, including a series of Thomas the Tank Engine models, and in later life worked on a sequence of exquisite model boats, often as gifts.

Although Robert and Wilma enjoyed some years of retirement together, travelling and relaxing, his health problems began to play an increasingly commanding role in his life. A brush with bladder cancer in his early 60s was overcome, but his lung problems continued to worsen.

By his 70s, Robert would go through a variety of treatments including various steroids and strong pain relief. Nothing was critically serious, but it all added up. Steroids bloated his body, while he was often left befuddled by the pain medication.

In some ways he was typical of a new challenge for the NHS – an increasing population of older people with multiple overlapping complaints, treatable yet chronic, who are living longer and thus making large demands on the health service over a significant length of time.

In recent years Robert’s world began to close in around him, a trip to the shops often the most he could achieve. In the last year or so he suffered a series of infections that resulted in stays in hospital. He was increasingly confused, and required more and more daily care.

In July of this year, Robert was taken back into hospital, to clear up lung and urinary infections, which were rendering him increasingly delirious. Over the next month, despite ups and downs day to day, he gradually declined.

Along with his wife’s daily visits, his children were able to join him for his last few weeks, and we were very lucky to be able to be with him while he was still present enough to be with us. His final days were surrounded by his family, and the end itself was peaceful.

There’s a lot more I could say, and perhaps I will do so somewhere at some point, but I just wanted to share my respect for – and I say this despite him being my father – one of the kindest, most selfless and considerate people I’ve ever met.

He was a highly intelligent, creative man, who never really understood how gifted he was. He was prone to gloom but could be delightfully silly, and was a purveyor of the best, most terrible dad jokes. I will miss him terribly.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter