It seems many of you don’t know what Magstock is, so time for a history lesson!

Today’s digital media world takes for granted how simple and accessible audio production for motion picture is.

Join me on an audio adventure to a time before everyone’s computer could be a DAW...

Today’s digital media world takes for granted how simple and accessible audio production for motion picture is.

Join me on an audio adventure to a time before everyone’s computer could be a DAW...

First, how was audio captured on set or in the field? Today’s digital tools allow for super portable recorders that record nearly limitless amounts of sound, or you could record directly to camera. But before digital, film couldn’t record sound (although some home formats did).

Yes, film captured the image and sound was captured separately. Say hello to the Nagra. Yes, wax recordings were a thing before this, but recording to analog tape was the first step to Sound Design flourishing. These were heavy, recorded two tracks and needed tape on reels.

It took 10 ‘D’ batteries and the length of recording depended on the quality you selected. The standard 5’ reels of 1/4” tape were only a few minutes at the highest setting. You could get larger reels, but the lid wouldn’t fit and it could not longer be slung over the shoulder.

Side note, as things moved to digital, Nagra thought people would want the same “experience” and released a model with the same weight and form factor but took swappable hard drives. Suffice to say this was a bad marketing decision.

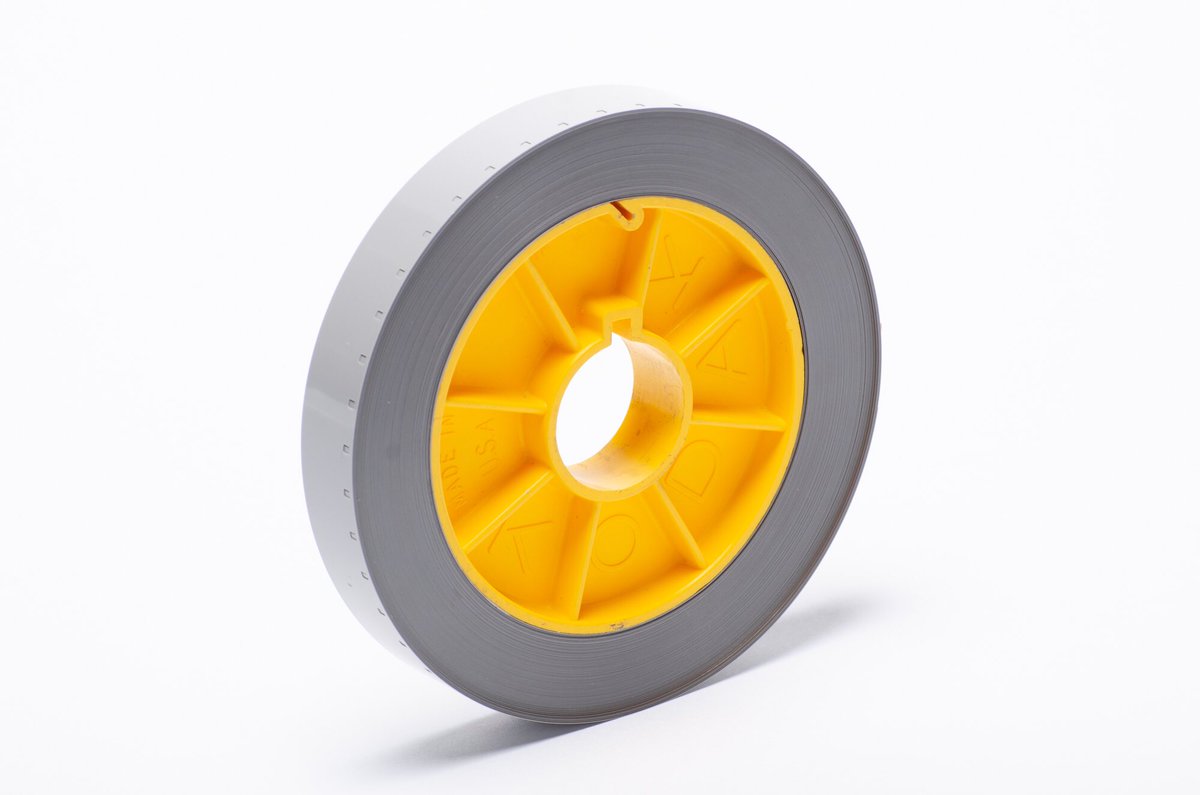

So you captured all your sound on set, now what? How do you edit that footage with the sound? Well the first step was to transfer to an analog tape that matched the size of the film. Magnetic stock or “Magstock”, pictured here is a small role the 16mm version.

The machines used to transfer the audio from the Nagra to Magstock were HUGE. And if you were trying to record a multitrack session in sync, you’d need a room full of them. The best part was you literally plugged the line out of the Nagra into them and it was in real time.

Oh and need to erase a tape? You’d use a degausser. They are still useful for data destruction today, but no one knew how to use them “correctly”, everyone had a different way that usually involved some type of dance. And when it fired you can feel the hair on your neck stand up.

You had a few options for how you would mark up your picture and sound to be synchronized. Most would use grease pencil on the film and either grease pencil or permanent marker on the tape. Mark the slate on both (where the clapper hits before the shot starts) and line them up.

If you want to see this in action, go watch De Palma’s “Blow Out” which has a pretty accurate depiction of the whole process (along with conspiracy and paranoia).

You could then use a sync block to manually advance the picture and sound together so it would stay in sync. Picture here is a squak box that would amplify the sound (I own both a tube and rectifier version of these, they make great guitar amps).

You could also use a moviola, which worked “vertically” having the film and sound pass up through the machine. These were loud and clunky, but could be quickly loaded.

Or you could use a flatbed editor, mostly made by Steenbeck. These were a bit more convenient to use but took up a lot of space. Here you can see the picture on the top platters and the Magstock passing through the bottom with the tape head right in the middle.

You would have bins of film with Magstock paper clipped to it. If you ever wondered why the terms “clips” and “bins” are still used in digital editing software, this is why.

Once you were happy with your edit, you’d send the audio to your sound editor and the picture’s edit decision list to the negative cutter. Their deliverables would be married to a master and the film’s sound track printed optically about 14 frames behind the picture beside it.

This is also why you can’t cut picture and sound in a single system in the film world. The optical sensor on a projector/flatbed is too far back to make easy and quick cuts. And yes, you were physically cutting and taping the clips together.

There’s an entire thread I could write about the sound design process, and how it involved a whole slew of special skills and equipment, but I don’t have enough experience in it first hand to justify going into detail.

So how do I know all this? Because I studied film production in University and my cohort was the last to be forced to do it for the first two years. Every project needed to be meticulously synced and cut and we paid for the Magstock out of pocket.

The idea behind it was if it took longer and was harder to do, you would put more thought into every cut, every choice. And sound effects? Yup, gotta source and transfer them manually one at a time so you better get good ones.

I don’t know if it made me a better editor or sound designer, but I certainly tackle all my projects in this way since this is the way I learned. I’m much more planned and thought out with my approach and less experimental because it was expensive and time consuming with tape.

It is possible to find tape machines and film editors in local film liaisons (like Toronto’s LIFT), but I don’t know if it’s worth the novelty of the experience. It is certainly worthwhile to at least try impose limitations to force you to think about sound tracks differently.

The thread came about thanks to this poll by the way. At least two of my followers have used Magstock, and at least one of them loved it.

https://twitter.com/proximity_sound/status/1294600652564369409?s=21 https://twitter.com/proximity_sound/status/1294600652564369409

https://twitter.com/proximity_sound/status/1294600652564369409?s=21 https://twitter.com/proximity_sound/status/1294600652564369409

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter