[THREAD: BAVARIA, BANKRUPTCY, BILLBOARDS]

1/65

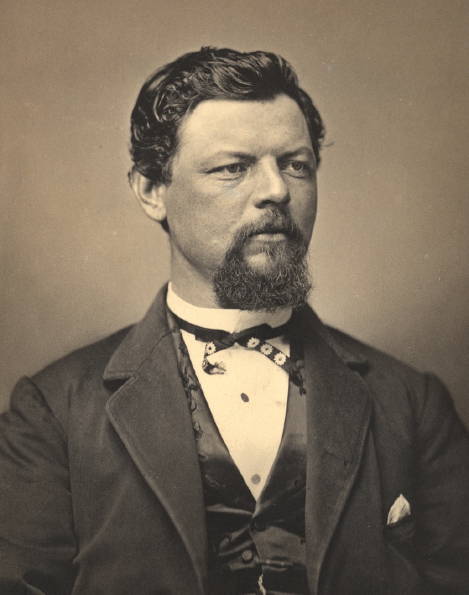

Once upon a time in Bavaria, Germany, lived a man named Jacob Best. There, he ran a small brewery and lived off it with his wife and 4 boys — Phillip, Jacob Jr., Charles, and Lorenz. Bavaria those days was a kingdom.

1/65

Once upon a time in Bavaria, Germany, lived a man named Jacob Best. There, he ran a small brewery and lived off it with his wife and 4 boys — Phillip, Jacob Jr., Charles, and Lorenz. Bavaria those days was a kingdom.

2/65

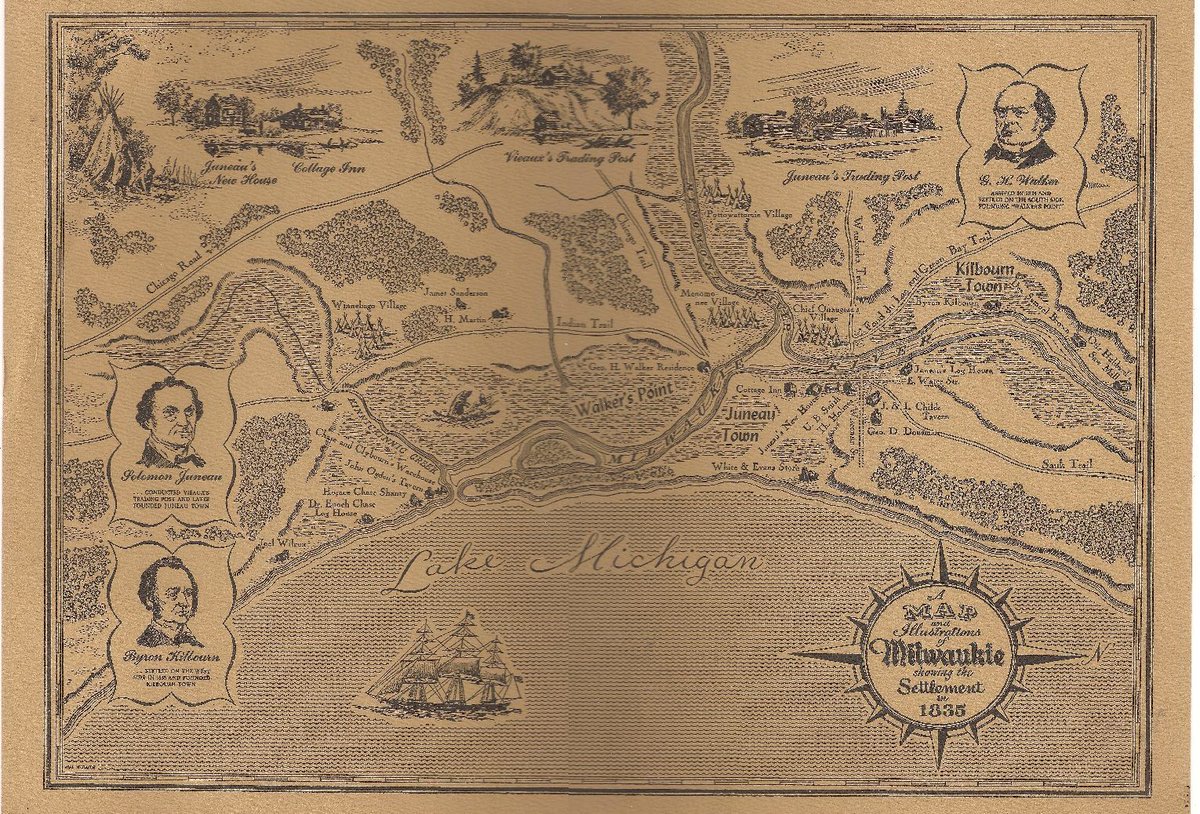

Then some time in the 1830s, Jacob Jr. and Charles emigrated to America and settled in this bustling new community of fellow Germans called Milwaukee. There, they set up a vinegar factory which did well. With time, the rest of the Best crossed the Atlantic too.

Then some time in the 1830s, Jacob Jr. and Charles emigrated to America and settled in this bustling new community of fellow Germans called Milwaukee. There, they set up a vinegar factory which did well. With time, the rest of the Best crossed the Atlantic too.

3/65

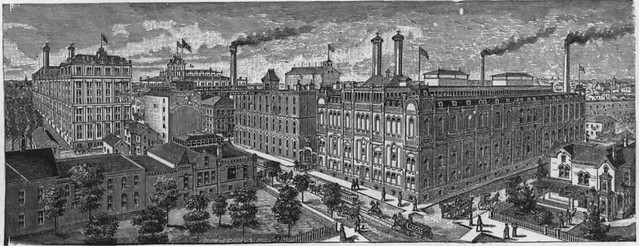

Once together in America, the Best enterprise graduated from vinegar to beer, something it was doing when back in Bavaria. The business was now The Empire Brewery on Chestnut Street Hill. As more Germans crossed into America, the demand for beer grew. Business prospered.

Once together in America, the Best enterprise graduated from vinegar to beer, something it was doing when back in Bavaria. The business was now The Empire Brewery on Chestnut Street Hill. As more Germans crossed into America, the demand for beer grew. Business prospered.

4/65

In 1844, the business was rebranded as Best & Company. The same year another young Bavarian found his way to the New World, this time a 23-year-old son of a cattle merchant from Ripmar, Bavaria. His name was Henry Lehman.

In 1844, the business was rebranded as Best & Company. The same year another young Bavarian found his way to the New World, this time a 23-year-old son of a cattle merchant from Ripmar, Bavaria. His name was Henry Lehman.

5/65

Henry settled in Montgomery, Alabama, where he set up a dry goods store by the name H. Lehman. 2 years later, Another young Bavarian hits America. This one was a Jew named Julius Ochs. By then, Charles had left family business and returned to making vinegar.

Henry settled in Montgomery, Alabama, where he set up a dry goods store by the name H. Lehman. 2 years later, Another young Bavarian hits America. This one was a Jew named Julius Ochs. By then, Charles had left family business and returned to making vinegar.

6/65

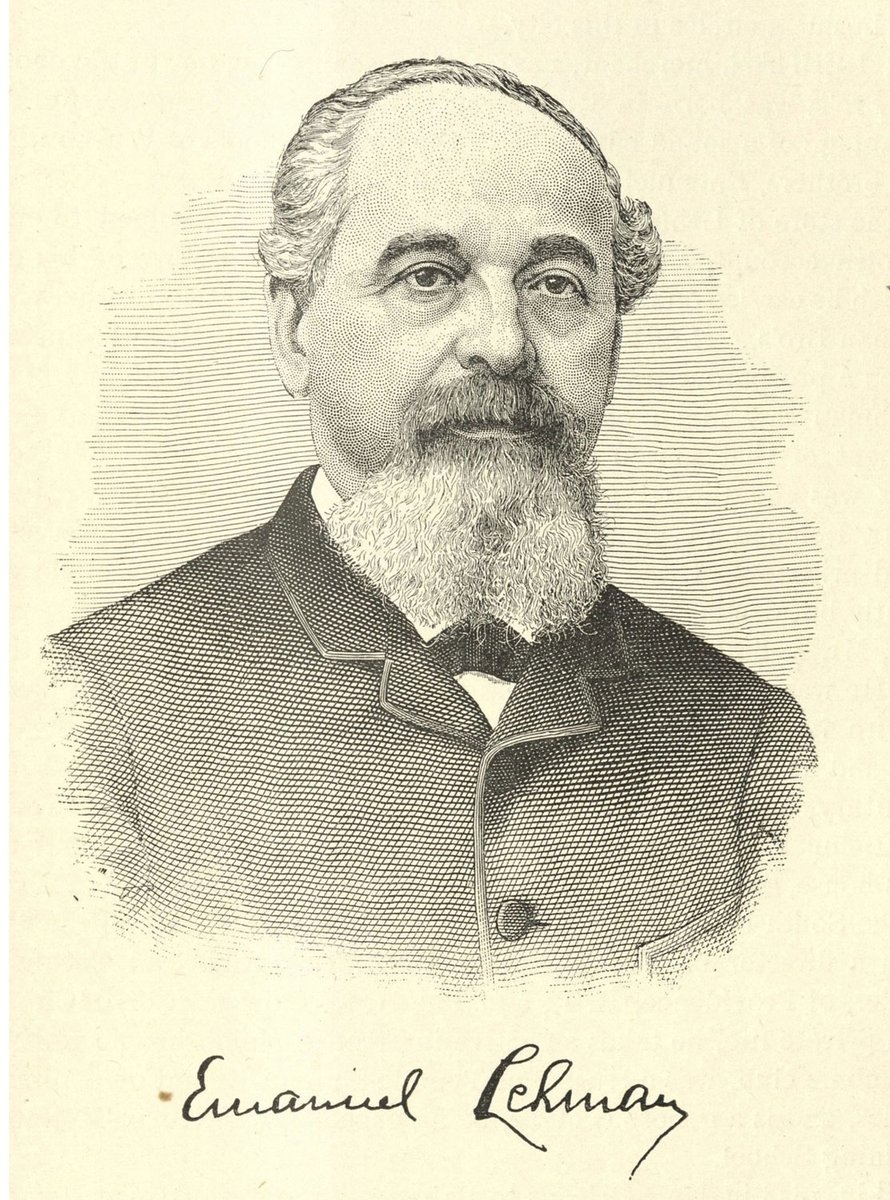

In 1847, Henry was joined by younger brother Emanuel and H. Lehman was renamed H. Lehman and Bro. All this while, more Germans kept streaming in. Coincidentally, all actors in this story happen to be German immigrants and all come from Bavaria. The last one is Bertha Levy.

In 1847, Henry was joined by younger brother Emanuel and H. Lehman was renamed H. Lehman and Bro. All this while, more Germans kept streaming in. Coincidentally, all actors in this story happen to be German immigrants and all come from Bavaria. The last one is Bertha Levy.

7/65

Bertha was a young Jewish girl who came to America in 1848. 5 years down the line, this girl would go on to marry Julius Ochs and give us the most important character of this story. More on that later.

First came 1850.

Two things happened that year.

Bertha was a young Jewish girl who came to America in 1848. 5 years down the line, this girl would go on to marry Julius Ochs and give us the most important character of this story. More on that later.

First came 1850.

Two things happened that year.

8/65

A. Charles was joined by younger brother Lorenz and the duo started Plank Road Brewery, the forerunner of what's today called Miller, and

B. Henry was joined by youngest brother Mayer and H. Lehman and Bro was renamed Lehman Brothers.

A. Charles was joined by younger brother Lorenz and the duo started Plank Road Brewery, the forerunner of what's today called Miller, and

B. Henry was joined by youngest brother Mayer and H. Lehman and Bro was renamed Lehman Brothers.

9/65

Cotton those days, thanks to an abundance of land and slaves, was Alabama's highest-grossing cash crop. Such was its value that the Lehmans even started accepting raw cotton as payment for merchandize, slowly morphing into a cotton-trading enterprise.

Cotton those days, thanks to an abundance of land and slaves, was Alabama's highest-grossing cash crop. Such was its value that the Lehmans even started accepting raw cotton as payment for merchandize, slowly morphing into a cotton-trading enterprise.

10/65

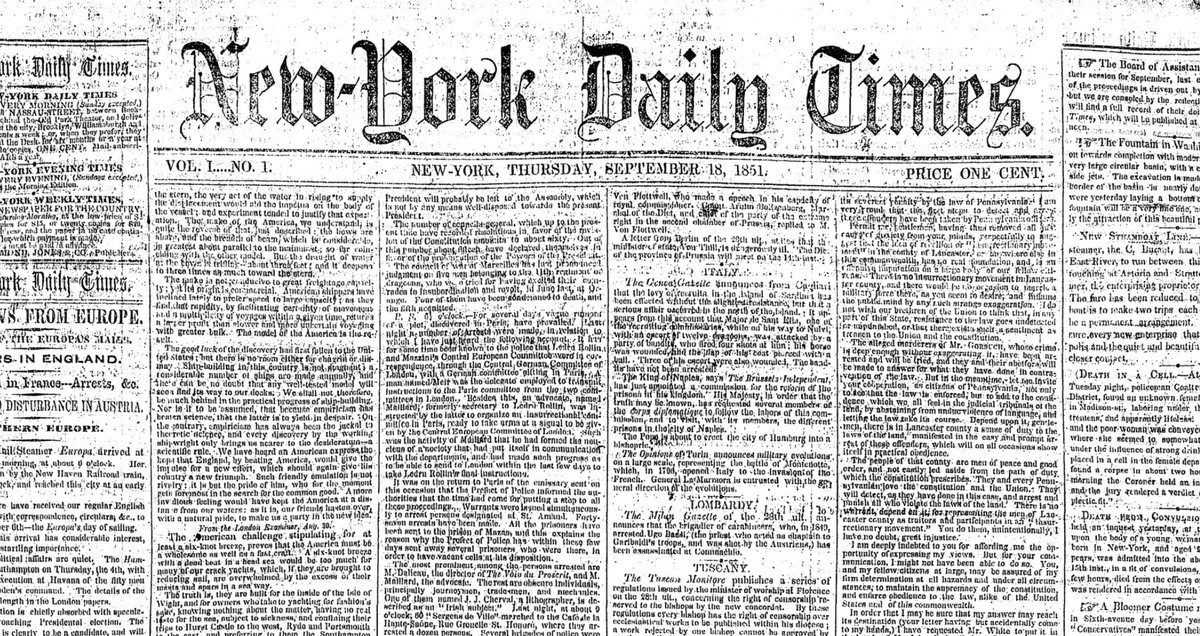

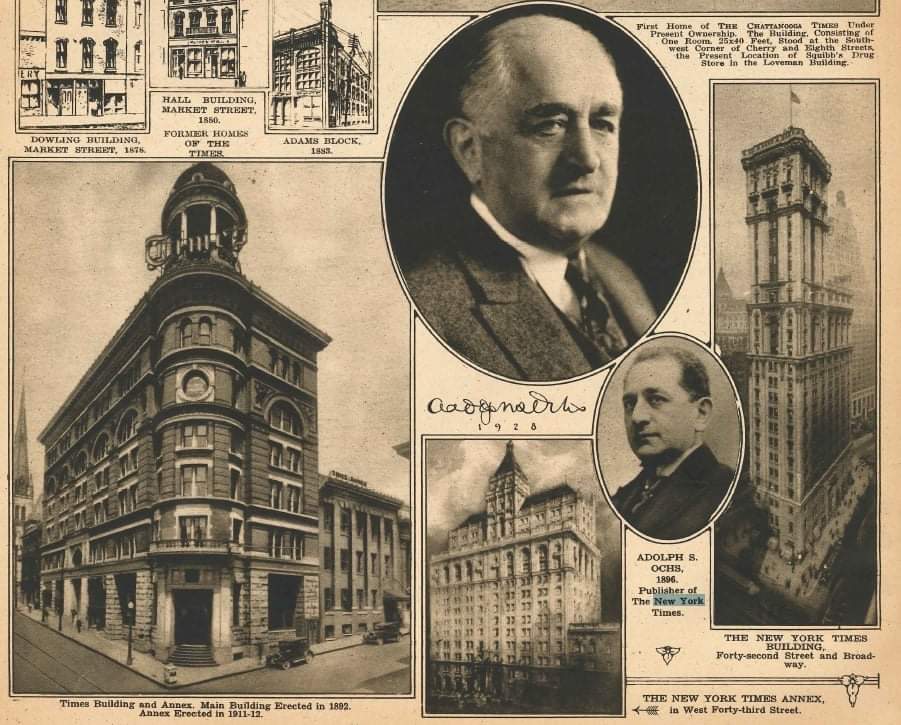

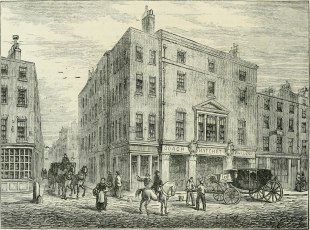

It was during this time that two Yankees, Henry Jarvis Raymond and George Jones, pooled in to launch a newspaper business named Raymond, Jones & Company. They named the paper New-York Daily Times and sold it for a penny a copy. That's about 30 cents in today's money.

It was during this time that two Yankees, Henry Jarvis Raymond and George Jones, pooled in to launch a newspaper business named Raymond, Jones & Company. They named the paper New-York Daily Times and sold it for a penny a copy. That's about 30 cents in today's money.

11/65

On Sep 14, 1857, the paper dropped Daily to become New-York Times (the hyphen wouldn't drop until Dec 1, 1896). Henry Lehman had already died of yellow fever and Bertha and Julius married by then. The following year, the Ochs had a boy. They named him Adolph.

On Sep 14, 1857, the paper dropped Daily to become New-York Times (the hyphen wouldn't drop until Dec 1, 1896). Henry Lehman had already died of yellow fever and Bertha and Julius married by then. The following year, the Ochs had a boy. They named him Adolph.

12/65

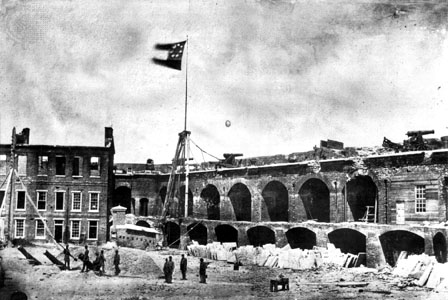

On April 12, 1861, barely a month into Lincoln's presidency, Gen. Beauregard's men bombed Fort Sumter officially inaugurating the American Civil War. The secession had already begun the previous year and all cotton states were part of the Confederacy now.

On April 12, 1861, barely a month into Lincoln's presidency, Gen. Beauregard's men bombed Fort Sumter officially inaugurating the American Civil War. The secession had already begun the previous year and all cotton states were part of the Confederacy now.

13/65

This conflict affected all involved in this story but the most hurt was the Best family, thanks to the war-driven fall in German immigration. By the time the dust settled, the brewery had gone to Phillip Best's son-in-law, a steamship captain named Frederick Pabst.

This conflict affected all involved in this story but the most hurt was the Best family, thanks to the war-driven fall in German immigration. By the time the dust settled, the brewery had gone to Phillip Best's son-in-law, a steamship captain named Frederick Pabst.

14/65

Remember the Lehmans? Yeah, they did well with cotton and about 5 years after the War, moved base to the continent's new financial epicenter, New York. Here, they, along with others, launched the New York Cotton Exchange. The offices were set up at 1, Hanover Sq.

Remember the Lehmans? Yeah, they did well with cotton and about 5 years after the War, moved base to the continent's new financial epicenter, New York. Here, they, along with others, launched the New York Cotton Exchange. The offices were set up at 1, Hanover Sq.

15/65

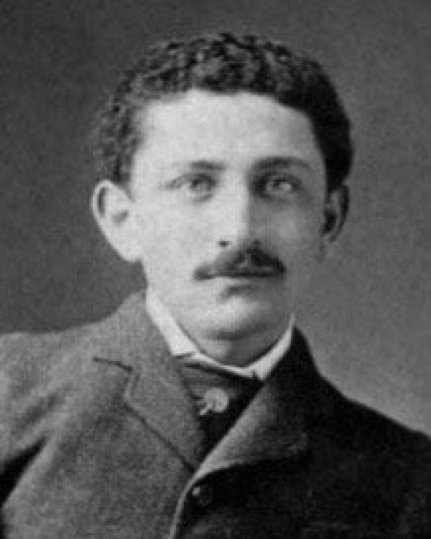

Meanwhile, young Adolph honed his printing and publishing skills at a newspaper called Knoxville Chronicles. By the time he turned 20, Adolph Ochs was a confident young publishing assistant raring to go his own. His opportunity came soon.

Meanwhile, young Adolph honed his printing and publishing skills at a newspaper called Knoxville Chronicles. By the time he turned 20, Adolph Ochs was a confident young publishing assistant raring to go his own. His opportunity came soon.

16/65

An 8-year-old Tennessee broadsheet named Chattanooga Times wasn't doing very well financially. Adolph saw opportunity and with $250 borrowed from his parents, bought a 50% into the aetiolating business. 2 more years and $5.5k later, it was 100%.

An 8-year-old Tennessee broadsheet named Chattanooga Times wasn't doing very well financially. Adolph saw opportunity and with $250 borrowed from his parents, bought a 50% into the aetiolating business. 2 more years and $5.5k later, it was 100%.

17/65

Adolph Ochs, son of two poor Jewish immigrants, was now owner of a major newspaper in America. But more awaited him. In the meantime Frederick Pabst renamed his business to Pabst Brewing Company. Lehman Brothers, by now, was member of the NYSE. The brand has arrived.

Adolph Ochs, son of two poor Jewish immigrants, was now owner of a major newspaper in America. But more awaited him. In the meantime Frederick Pabst renamed his business to Pabst Brewing Company. Lehman Brothers, by now, was member of the NYSE. The brand has arrived.

18/65

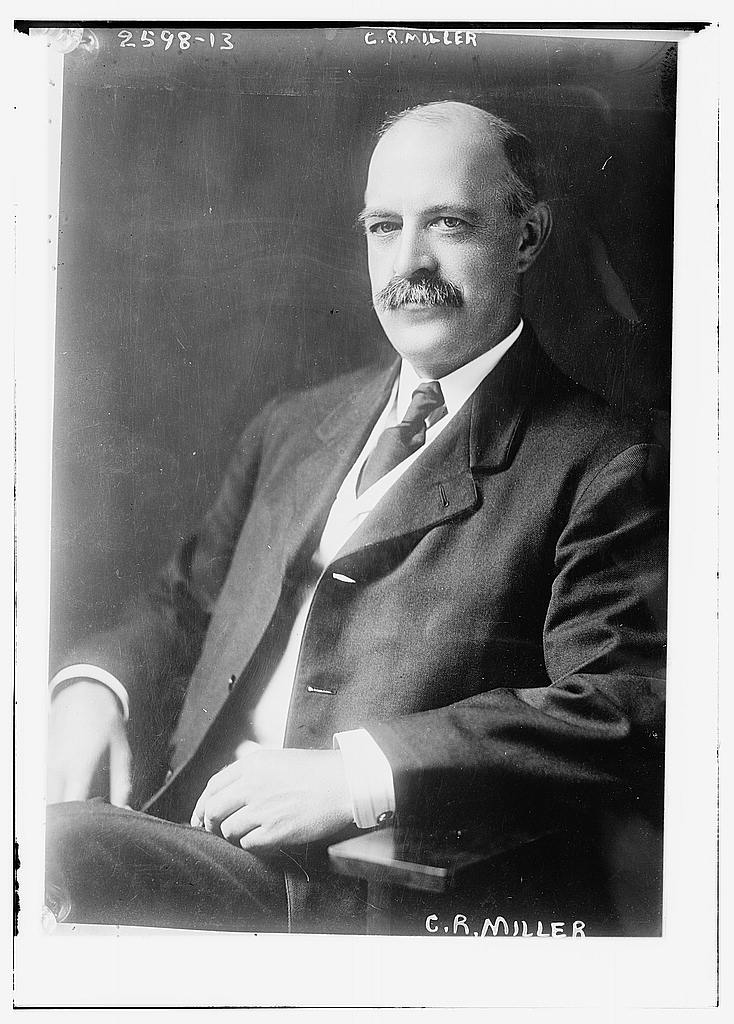

After George Jones' death in 1891, Charles Miller and a bunch of editors pooled in a million dollars to buy out the paper and publish it under a new banner, the New York Times Publishing Company. This, however, didn't save the paper from a major setback 2 years later.

After George Jones' death in 1891, Charles Miller and a bunch of editors pooled in a million dollars to buy out the paper and publish it under a new banner, the New York Times Publishing Company. This, however, didn't save the paper from a major setback 2 years later.

19/65

The Panic of 1893. But let's rewind a bit. A small detour to 1890, Argentina. The wheat crop there had failed miserably that year. This was the first domino. Triggered by this, fell the second. The Revolución del Parque.

The Panic of 1893. But let's rewind a bit. A small detour to 1890, Argentina. The wheat crop there had failed miserably that year. This was the first domino. Triggered by this, fell the second. The Revolución del Parque.

20/65

Although crushed in a mere 3 days, the revolution did manage to score a presidential resignation. But the damage had already been done. European investments in the country, heavily promoted by Baring Brothers, started drying up. Who wants to invest in an unstable economy?

Although crushed in a mere 3 days, the revolution did manage to score a presidential resignation. But the damage had already been done. European investments in the country, heavily promoted by Baring Brothers, started drying up. Who wants to invest in an unstable economy?

21/65

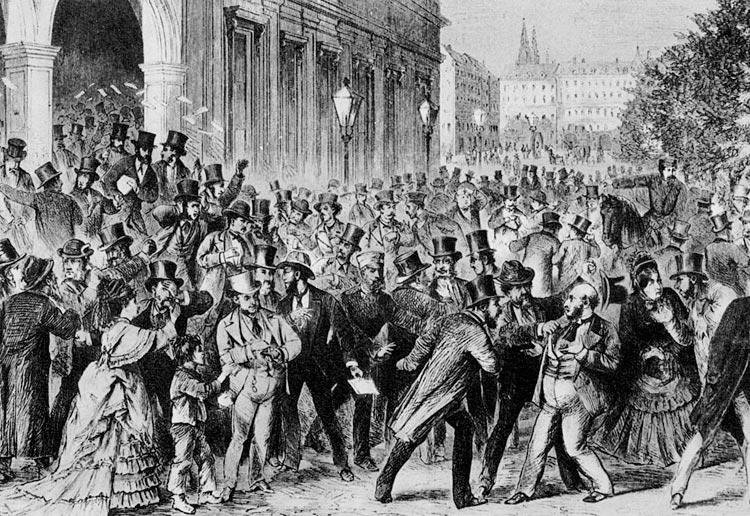

This triggered a panic across Europe where many businesses stood heavily invested in the US Treasury bonds. By 1893, wheat prices had crashed worldwide further aggravating an already problematic situation. A panic in London triggered gold runs in America.

This triggered a panic across Europe where many businesses stood heavily invested in the US Treasury bonds. By 1893, wheat prices had crashed worldwide further aggravating an already problematic situation. A panic in London triggered gold runs in America.

22/65

America was now in a deep depression. We know it as the Panic of 1893. This affected many businesses one of them, the New-York Times. By 1896, circulation was down to 9k and the paper was losing $1k a day. Ochs saw opportunity. Actually, he was shown opportunity.

America was now in a deep depression. We know it as the Panic of 1893. This affected many businesses one of them, the New-York Times. By 1896, circulation was down to 9k and the paper was losing $1k a day. Ochs saw opportunity. Actually, he was shown opportunity.

23/65

It was Henry Alloway, a journalist. On his tip, Ochs borrowed $75k and bought out the troubled newspaper. His first step? Drop the hyphen. The paper was now called New York Times. Pabst, meanwhile, was starting to foray into the hotel business. Interesting times ahead.

It was Henry Alloway, a journalist. On his tip, Ochs borrowed $75k and bought out the troubled newspaper. His first step? Drop the hyphen. The paper was now called New York Times. Pabst, meanwhile, was starting to foray into the hotel business. Interesting times ahead.

24/65

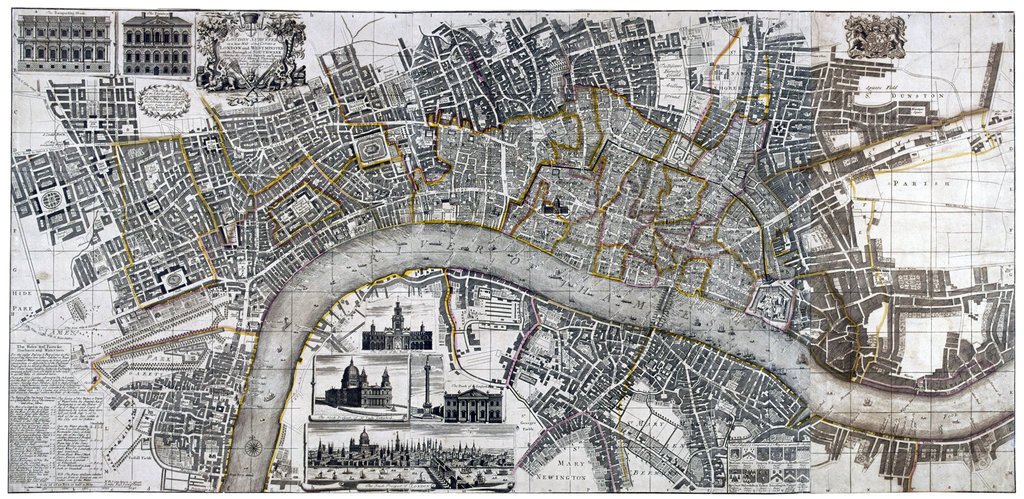

One last rewind here. 300 years. Long time, I know, but bear with me, it'll all zoom past in a jiffy. Back to when Manhattan was a swampy island, home to Lenape Indians. But we're not going there. Instead, we're going to London. The City of Westminster to be precise.

One last rewind here. 300 years. Long time, I know, but bear with me, it'll all zoom past in a jiffy. Back to when Manhattan was a swampy island, home to Lenape Indians. But we're not going there. Instead, we're going to London. The City of Westminster to be precise.

25/65

There was a street. It ran east-west between St. Martin's Lane and Drury Lane and cut through a parcel called Elms back then. With time, the street was renamed first Seven Acres and then Long Acre. Just the street, not the area it ran through. That remained Elms

There was a street. It ran east-west between St. Martin's Lane and Drury Lane and cut through a parcel called Elms back then. With time, the street was renamed first Seven Acres and then Long Acre. Just the street, not the area it ran through. That remained Elms

26/65

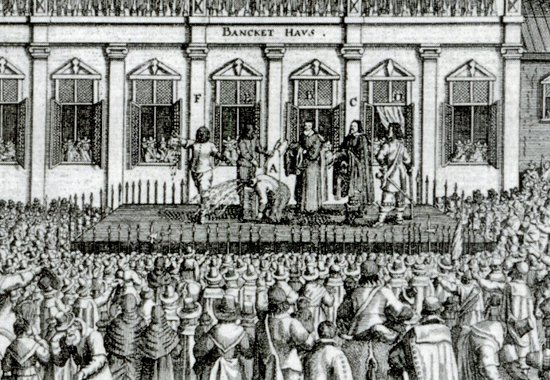

Sometime around 1626, Charles I decided to name the area after the street and the whole place became Long Acre. The street was home to many big and controversial names of the time including a certain Oliver Cromwell who eventually head Charles I beheaded, but I digress.

Sometime around 1626, Charles I decided to name the area after the street and the whole place became Long Acre. The street was home to many big and controversial names of the time including a certain Oliver Cromwell who eventually head Charles I beheaded, but I digress.

27/65

Besides its controversial residents, Long Acre also hosted a thriving coachmaking industry. If you saw a horse-drawn carriage anywhere in the city back then, it most likely came from a workshop here. Today, coachmakers have given way to car dealers.

Besides its controversial residents, Long Acre also hosted a thriving coachmaking industry. If you saw a horse-drawn carriage anywhere in the city back then, it most likely came from a workshop here. Today, coachmakers have given way to car dealers.

28/65

While Charles I was renaming and renovating Long Acre in London, the Dutch were gentrifying a marshy Island across the Atlantic. A certain Peter Minuit had just bought it for the Dutch West India Company for the equivalent of 60 guilders. It was called Manhattan.

While Charles I was renaming and renovating Long Acre in London, the Dutch were gentrifying a marshy Island across the Atlantic. A certain Peter Minuit had just bought it for the Dutch West India Company for the equivalent of 60 guilders. It was called Manhattan.

29/65

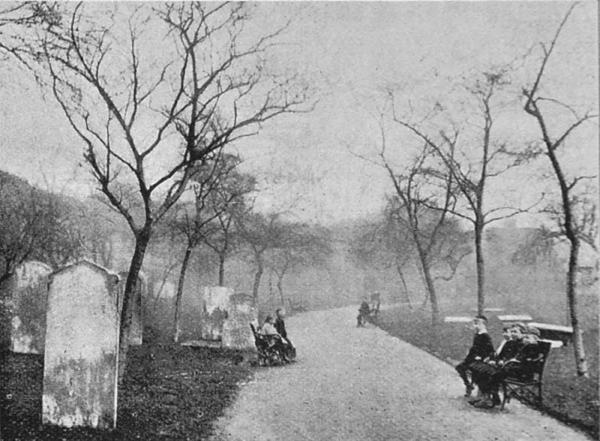

Those days, the island looked slightly different from what it does today. At least landscape-wise at any rate. Where 10th Ave. and 40th St. meet today, 3 streams did then. Once merged, the new stream snaked through the Reed Valley before emptying into the Hudson.

Those days, the island looked slightly different from what it does today. At least landscape-wise at any rate. Where 10th Ave. and 40th St. meet today, 3 streams did then. Once merged, the new stream snaked through the Reed Valley before emptying into the Hudson.

30/65

Thanks to an abundant bounty of freshwater fish, this stream earned the name, Grote Kil (Great Kill in English). The name also applied to a tiny Reed Valley settlement somewhere along the stream. With time, this region became a carriage-building hub.

Thanks to an abundant bounty of freshwater fish, this stream earned the name, Grote Kil (Great Kill in English). The name also applied to a tiny Reed Valley settlement somewhere along the stream. With time, this region became a carriage-building hub.

31/65

In about a century, the area fell into the hands of a Sons of Anarchy founding member named John Morin Scott. Scott was also a general in Washington's army during the American Revolution and continued to hold Grote Kil well into independence.

In about a century, the area fell into the hands of a Sons of Anarchy founding member named John Morin Scott. Scott was also a general in Washington's army during the American Revolution and continued to hold Grote Kil well into independence.

32/65

Within a century of American independence, much of the area was bought by a John Jacob Astor, America's first multimillionaire, who later made a killing selling lots to hotels and businesses. The countryside around the area was popular with horse breeders.

Within a century of American independence, much of the area was bought by a John Jacob Astor, America's first multimillionaire, who later made a killing selling lots to hotels and businesses. The countryside around the area was popular with horse breeders.

33/65

By the late 19th century, William Henry Vanderbilt had inherited about a hundred million dollars from daddy Cornelius, become the richest bloke on the continent, and invested much of it in the horse business in the Grote Kil region.

The American Horse Exchange.

By the late 19th century, William Henry Vanderbilt had inherited about a hundred million dollars from daddy Cornelius, become the richest bloke on the continent, and invested much of it in the horse business in the Grote Kil region.

The American Horse Exchange.

34/65

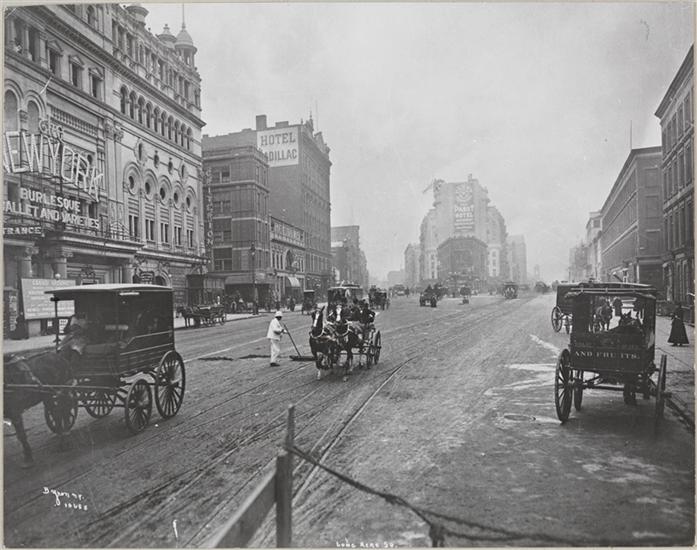

American Horse Exchange was not the only such business in the area though. By now, it was practically a hub of horse and carriage industry. Reminds you of a similar district in London? Sure did to the authorities back then who decided to name the area Longacre.

American Horse Exchange was not the only such business in the area though. By now, it was practically a hub of horse and carriage industry. Reminds you of a similar district in London? Sure did to the authorities back then who decided to name the area Longacre.

35/65

In 1878, while Vanderbilt was busy trading literal horses and expanding his empire in Manhattan, a different kind of empire was in the works about 800 miles away in Tennessee. That year, a 20-year-old bought a controlling stake in Chattanooga Times for $250.

In 1878, while Vanderbilt was busy trading literal horses and expanding his empire in Manhattan, a different kind of empire was in the works about 800 miles away in Tennessee. That year, a 20-year-old bought a controlling stake in Chattanooga Times for $250.

36/65

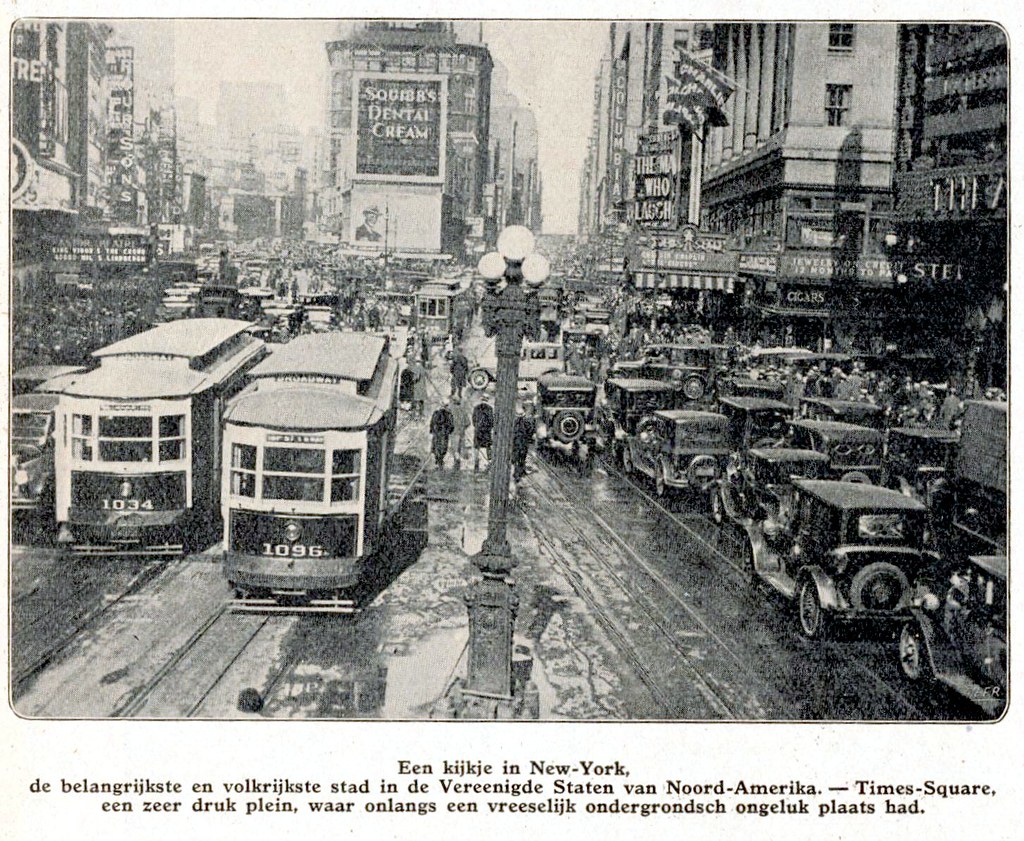

21 years later, Longacre was a very different place. Bustling with business and activities of all kinds, the place had now a commercial reputation very different from its carriage-making days. The convergence of our 3 actors in NYC is almost complete.

21 years later, Longacre was a very different place. Bustling with business and activities of all kinds, the place had now a commercial reputation very different from its carriage-making days. The convergence of our 3 actors in NYC is almost complete.

37/65

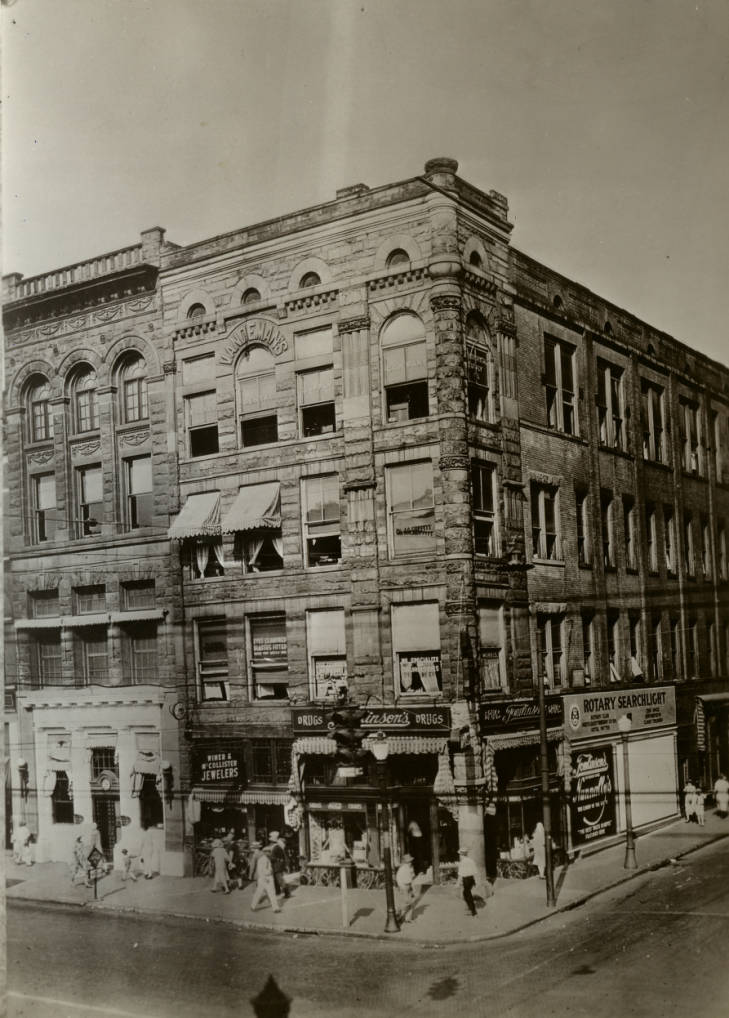

The Lehmans were already in the city, as was Ochs. What remained was Pabst. This completed in 1899 when the beer company leased a 9-storey building on Longacre Square to open Pabst Hotel. Now we have all 3 in New York — Lehman Brothers, the New York Times, and Pabst.

The Lehmans were already in the city, as was Ochs. What remained was Pabst. This completed in 1899 when the beer company leased a 9-storey building on Longacre Square to open Pabst Hotel. Now we have all 3 in New York — Lehman Brothers, the New York Times, and Pabst.

38/65

Pabst Hotel had a rather small footprint, but its underground rathskeller (basement pub) extended way out, practically under the sidewalk. Those days this wasn't illegal. Also extended way out, its upper storeys. This was not legal but not uncommon either.

Pabst Hotel had a rather small footprint, but its underground rathskeller (basement pub) extended way out, practically under the sidewalk. Those days this wasn't illegal. Also extended way out, its upper storeys. This was not legal but not uncommon either.

39/65

That year, Lehman Brothers underwrote its first public offering, formally entering the non-commodity financial business. This public offering was for the International Steam Pump Company. Lehman Brothers was now an investment banking and underwriting firm.

That year, Lehman Brothers underwrote its first public offering, formally entering the non-commodity financial business. This public offering was for the International Steam Pump Company. Lehman Brothers was now an investment banking and underwriting firm.

40/65

New York entered the 20th century with a series of landmark infrastructure projects, one of them the subway. Between 1900 and 1904 the city's first subway line, the IRT, was laid. This was an ambitious project and was helmed by the Subway Realty Company.

New York entered the 20th century with a series of landmark infrastructure projects, one of them the subway. Between 1900 and 1904 the city's first subway line, the IRT, was laid. This was an ambitious project and was helmed by the Subway Realty Company.

41/65

This subway project was problematic for Pabst as one of the lines, the Main Line, ran along Broadway. Under the sidewalk. Right through the hotel's rathskeller. The subway company took possession of the entire stretch under the sidewalk and Pabst lost its rathskeller.

This subway project was problematic for Pabst as one of the lines, the Main Line, ran along Broadway. Under the sidewalk. Right through the hotel's rathskeller. The subway company took possession of the entire stretch under the sidewalk and Pabst lost its rathskeller.

42/65

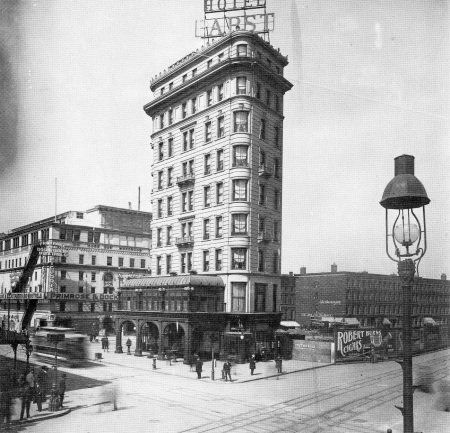

Seeing no point running the hotel without its rathskeller, Pabst started looking for a buyer. The same year, Ochs decided to move out of its property near the City Hall and build a new one at Longacre Square, the new downtown. Within weeks, the hotel building was sold.

Seeing no point running the hotel without its rathskeller, Pabst started looking for a buyer. The same year, Ochs decided to move out of its property near the City Hall and build a new one at Longacre Square, the new downtown. Within weeks, the hotel building was sold.

43/65

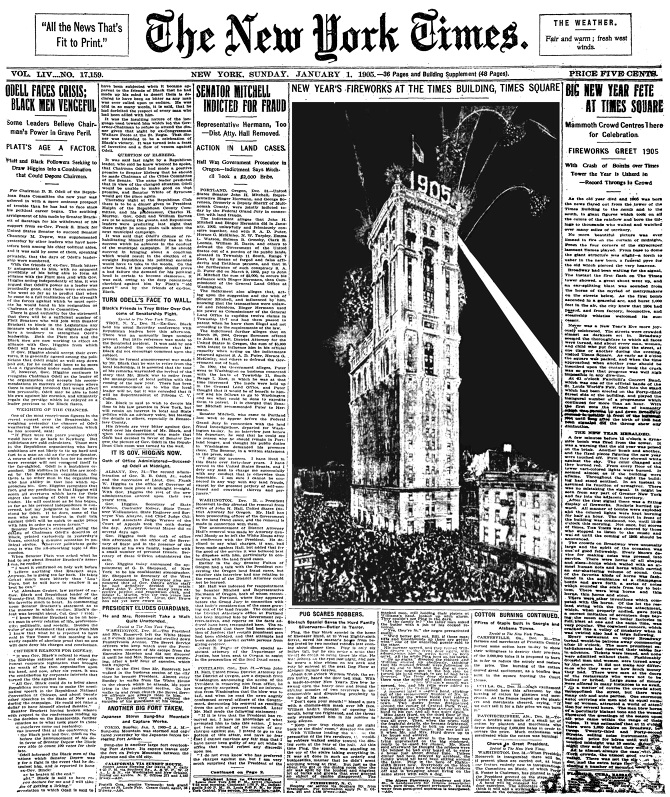

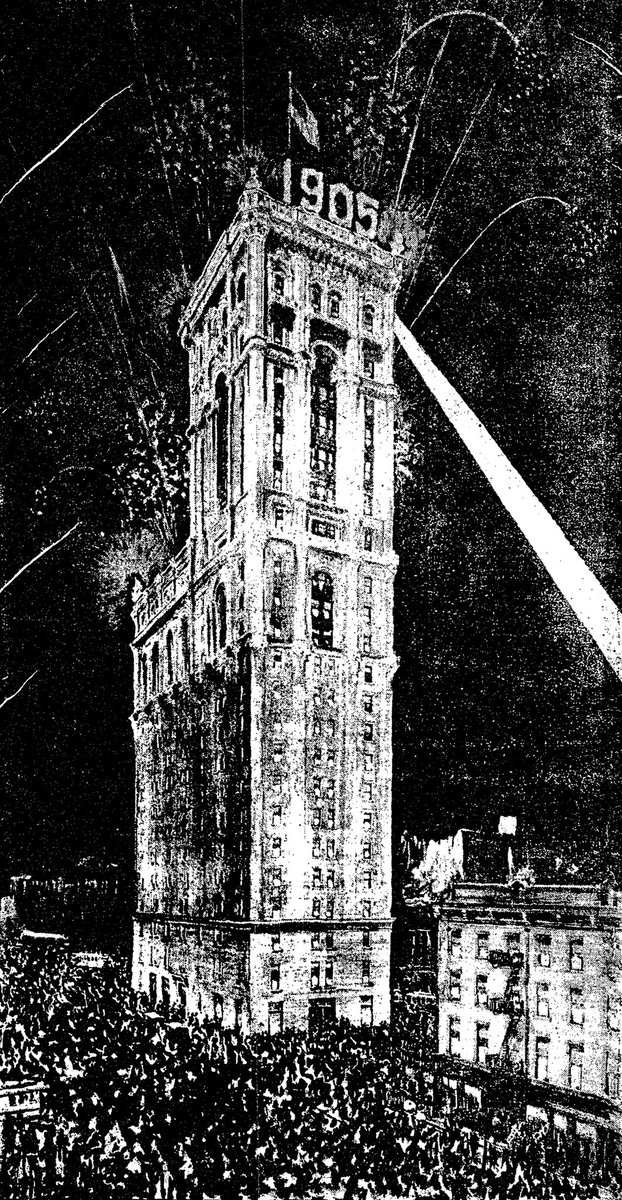

The building was demolished and a new one, a skyscraper named Times Building took its place. The construction wasn't yet complete when the NYT decided to move in anyway on the first day of 1905. The New Year's Eve was celebrated with rooftop fireworks.

The building was demolished and a new one, a skyscraper named Times Building took its place. The construction wasn't yet complete when the NYT decided to move in anyway on the first day of 1905. The New Year's Eve was celebrated with rooftop fireworks.

44/65

This celebration was to promote the paper's new office building and proved a spectacular success. About 20k gathered in Longacre Square to witness the event. The very next morning, Ochs and his employees officially moved into the new 25-floor building.

This celebration was to promote the paper's new office building and proved a spectacular success. About 20k gathered in Longacre Square to witness the event. The very next morning, Ochs and his employees officially moved into the new 25-floor building.

45/65

Times Building was known by many names. Times Tower, 1475 Broadway, and NYT Building. By April, 1906, Adolph Ochs convinced the authorities to rename the area after his business and Longacre Square became Times Square. The building was now One Times Square.

Times Building was known by many names. Times Tower, 1475 Broadway, and NYT Building. By April, 1906, Adolph Ochs convinced the authorities to rename the area after his business and Longacre Square became Times Square. The building was now One Times Square.

46/65

For the New Year's Eve in 1908, a time ball was added as a new publicity gimmick. This involved a lit ball slowly lowered down the building's flag pole at midnight.

The famous Times Square ball drop was born.

The tradition continues till today.

For the New Year's Eve in 1908, a time ball was added as a new publicity gimmick. This involved a lit ball slowly lowered down the building's flag pole at midnight.

The famous Times Square ball drop was born.

The tradition continues till today.

47/65

In 1913, while still maintaining ownership over the building, the NYT moved out to a different location. Then came the First World War. Then came peace. Then came women's suffrage via the 19th Amendment. That was 1920. Women could now vote. Finally!

In 1913, while still maintaining ownership over the building, the NYT moved out to a different location. Then came the First World War. Then came peace. Then came women's suffrage via the 19th Amendment. That was 1920. Women could now vote. Finally!

48/65

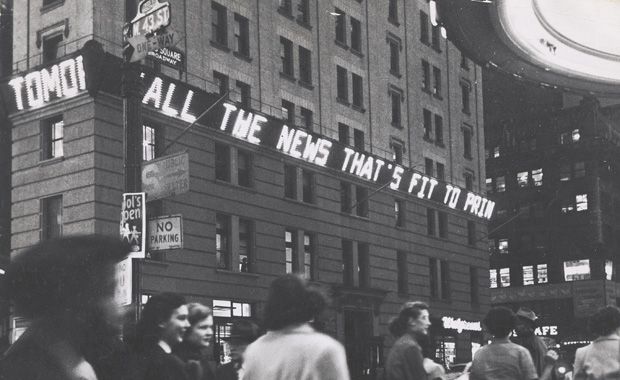

With peace came prosperity, even if short-lived. And prosperity meant more business. Things were now looking upbeat. Everywhere in general and at Times Square in particular. In 1928, One Times Square saw its first piece of glitz. In the shape of a news ticker.

With peace came prosperity, even if short-lived. And prosperity meant more business. Things were now looking upbeat. Everywhere in general and at Times Square in particular. In 1928, One Times Square saw its first piece of glitz. In the shape of a news ticker.

49/65

On Nov 6, 1928, the Motogram Company installed what it called its first Motograph News Bulletin, eventually referred to as the zipper. The ticker sat near the base of the building and consisted of about 15k lightbulbs moved with a chain conveyor system.

On Nov 6, 1928, the Motogram Company installed what it called its first Motograph News Bulletin, eventually referred to as the zipper. The ticker sat near the base of the building and consisted of about 15k lightbulbs moved with a chain conveyor system.

50/65

The first news it flashed was of Herbert Hoover's presidential victory on the same day. The zipper remains a prominent fixture till today although the lightbulbs have been replaced with LEDs. For the next several years, it'd remain the sole attraction in the square.

The first news it flashed was of Herbert Hoover's presidential victory on the same day. The zipper remains a prominent fixture till today although the lightbulbs have been replaced with LEDs. For the next several years, it'd remain the sole attraction in the square.

51/65

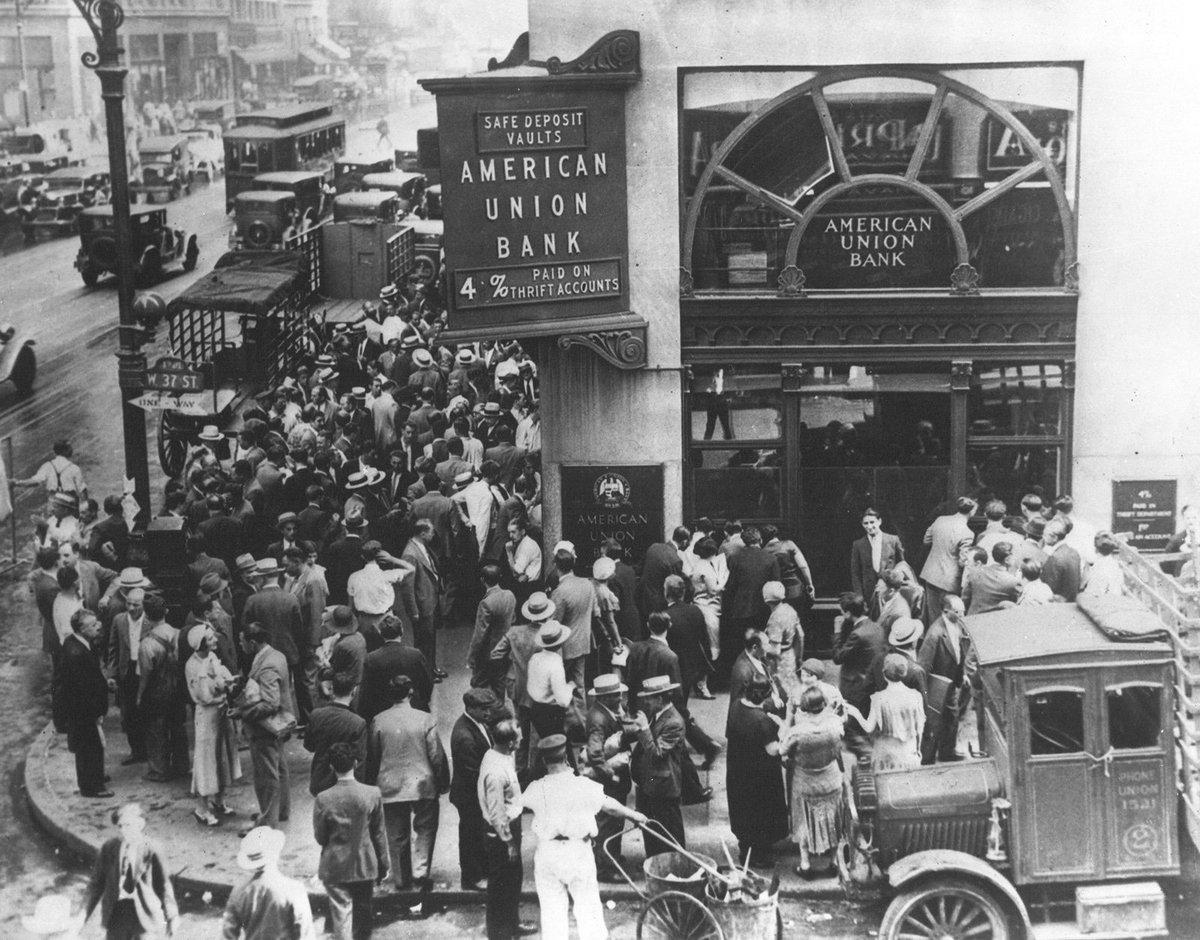

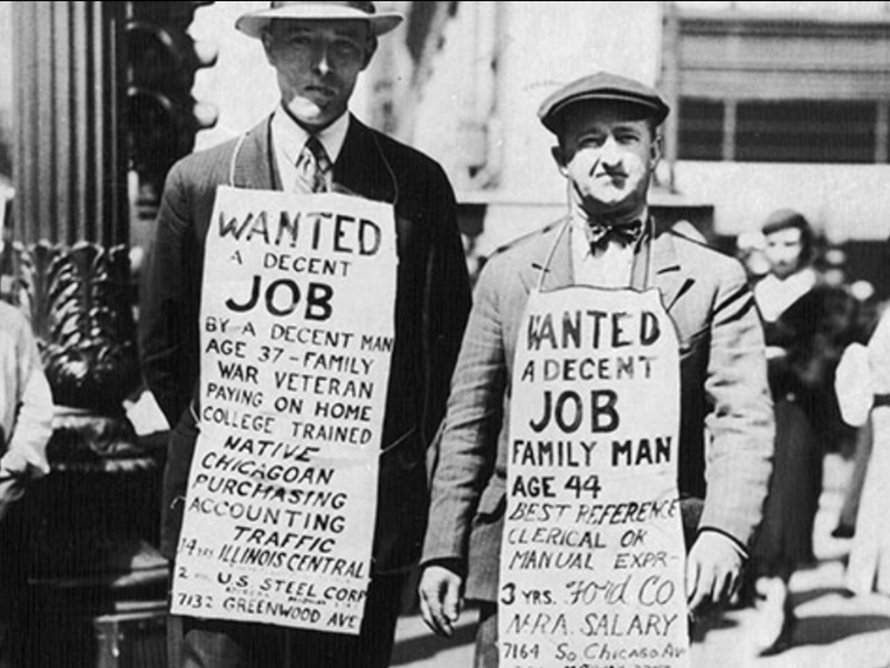

Barely a year after the zipper's launch, though, America plunged into one of the darkest chapters in its history.

The Great Depression.

By the time it was over, Ochs was dead and the Gray Lady now belonged to son-in-law Arthur Hays Sulzberger.

Barely a year after the zipper's launch, though, America plunged into one of the darkest chapters in its history.

The Great Depression.

By the time it was over, Ochs was dead and the Gray Lady now belonged to son-in-law Arthur Hays Sulzberger.

52/65

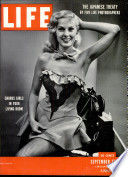

Although I called it Gray Lady already, it wouldn't be until September, 1951, that the name world actually be used for the NYT. Credit goes to a Life magazine article by columnist Meyer Berger. Actually, the full sobriquet he coined was the Old Gray Lady.

Although I called it Gray Lady already, it wouldn't be until September, 1951, that the name world actually be used for the NYT. Credit goes to a Life magazine article by columnist Meyer Berger. Actually, the full sobriquet he coined was the Old Gray Lady.

53/65

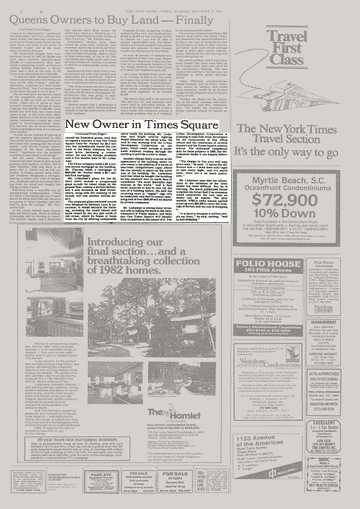

Over the following decades, One Times Square changed several hands finally landing in the hands of one Lawrence Linksman. The year was 1982. Alas, even Linksman couldn't hold on to it much longer and barely a decade later, filed for bankruptcy.

Over the following decades, One Times Square changed several hands finally landing in the hands of one Lawrence Linksman. The year was 1982. Alas, even Linksman couldn't hold on to it much longer and barely a decade later, filed for bankruptcy.

54/65

Linksman's bankruptcy led to a 27-million-dollar deal giving the building's ownership to Lehman Brothers, now one of world's top investment banking heavyweights. The new owner didn't bother renovating the interior for new tenants though. Never did. https://www.businessinsider.com.au/new-years-eve-ball-at-one-times-square-2014-12

Linksman's bankruptcy led to a 27-million-dollar deal giving the building's ownership to Lehman Brothers, now one of world's top investment banking heavyweights. The new owner didn't bother renovating the interior for new tenants though. Never did. https://www.businessinsider.com.au/new-years-eve-ball-at-one-times-square-2014-12

55/65

It didn't see much value in rental or lease thanks to its limited usable space. But the prime location meant advertising opportunity. Lehman Brothers decided to use the entire exterior façade as rental ad space. There was untold money to be made. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323476304578199310470733342

It didn't see much value in rental or lease thanks to its limited usable space. But the prime location meant advertising opportunity. Lehman Brothers decided to use the entire exterior façade as rental ad space. There was untold money to be made. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323476304578199310470733342

56/65

Soon, giant billboards were being mounted on One Times Square transforming the whole square into an enormous advertising wonderland. With time, static billboards gave way to dazzling video signs with players like Walgreens, Sony, and NASDAQ hopping in.

Soon, giant billboards were being mounted on One Times Square transforming the whole square into an enormous advertising wonderland. With time, static billboards gave way to dazzling video signs with players like Walgreens, Sony, and NASDAQ hopping in.

57/65

In 1997, Lehman Brothers sold off the building to its current owners, Jamestown L. P. for $117m. A little over a decade later, Lehman Brothers itself went bankrupt.

Times Square. continued to dazzle, bankruptcies notwithstanding.

https://therealdeal.com/new-research/topics/property/1-times-square/

In 1997, Lehman Brothers sold off the building to its current owners, Jamestown L. P. for $117m. A little over a decade later, Lehman Brothers itself went bankrupt.

Times Square. continued to dazzle, bankruptcies notwithstanding.

https://therealdeal.com/new-research/topics/property/1-times-square/

58/65

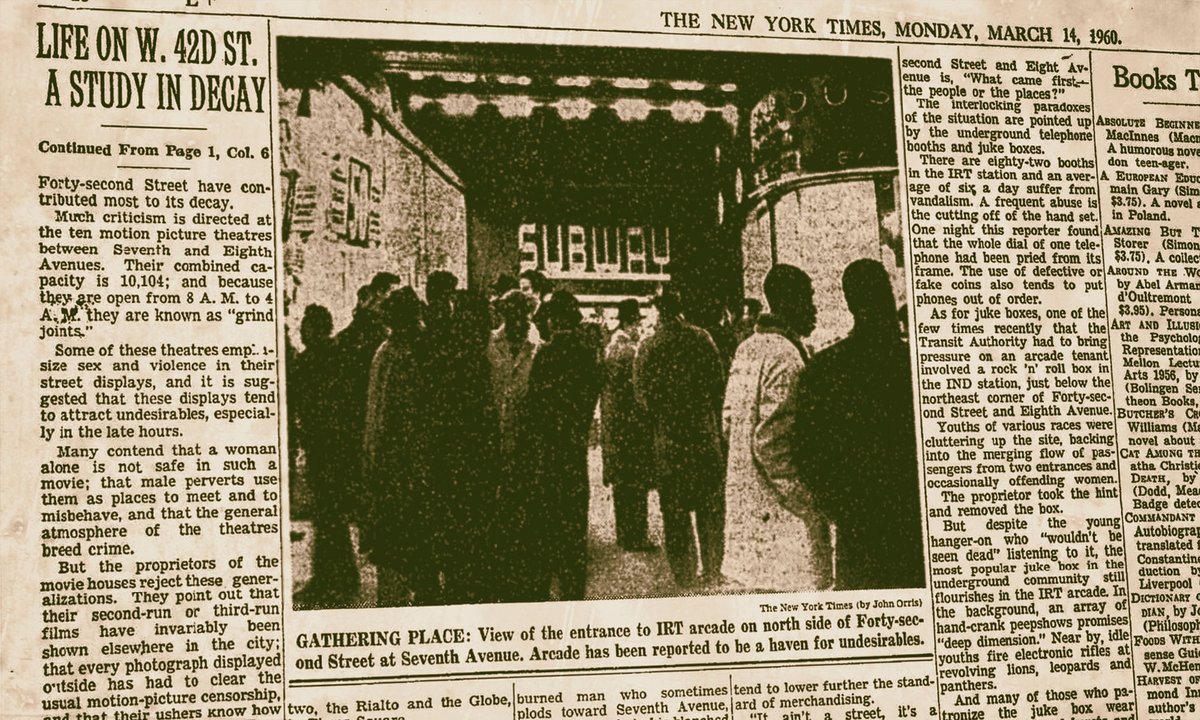

Behind the ritzy façade though, the area was a hotbed of crime until as recently as the 2000s. At one point it was described as the "worst block in NYC." There was porn in cinema and hustling in the street. Even the NYPD preferred starting away.

https://www.nytimes.com/1960/03/14/archives/life-on-w-42d-st-a-study-in-decay-life-on-w-42d-st-a-study-in-decay.html

Behind the ritzy façade though, the area was a hotbed of crime until as recently as the 2000s. At one point it was described as the "worst block in NYC." There was porn in cinema and hustling in the street. Even the NYPD preferred starting away.

https://www.nytimes.com/1960/03/14/archives/life-on-w-42d-st-a-study-in-decay-life-on-w-42d-st-a-study-in-decay.html

59/65

At one point, property taxes from all of Times Square came to a grand total of $6 million, less than what a small Manhattan office building would generate annually in 1984 dollars. That's how abandoned the area was.

But the signs kept flashing.

At one point, property taxes from all of Times Square came to a grand total of $6 million, less than what a small Manhattan office building would generate annually in 1984 dollars. That's how abandoned the area was.

But the signs kept flashing.

60/65

These signs are officially called "spectaculars," the biggest of those, "jumbotron." Sony was the first to install one although today, the largest jumbotron is run by Walgreens. Over the years, the square has seen rapid gentrification in terms of lighting and glamor.

These signs are officially called "spectaculars," the biggest of those, "jumbotron." Sony was the first to install one although today, the largest jumbotron is run by Walgreens. Over the years, the square has seen rapid gentrification in terms of lighting and glamor.

61/65

Today, the square receives no fewer than 130 million pedestrian visitors annually. That's more than any Disney property in the world. The signs here have flashed everything from TikTok to Pornhub to Xi Jinping to...

Ram Mandir.

Today, the square receives no fewer than 130 million pedestrian visitors annually. That's more than any Disney property in the world. The signs here have flashed everything from TikTok to Pornhub to Xi Jinping to...

Ram Mandir.

62/65

A giant Ram and his planned temple lit up one of the billboards here on Aug 5, 2020. The 12-hour stay cost Ram and his boys between $5k and 10 times as much.

So that's the story of Indian diaspora's most expensive plea for validation ever.

A giant Ram and his planned temple lit up one of the billboards here on Aug 5, 2020. The 12-hour stay cost Ram and his boys between $5k and 10 times as much.

So that's the story of Indian diaspora's most expensive plea for validation ever.

63/65

There's a few interesting observations in this story.

The Best business went belly-up in 1863.

The NYT went broke in 1896.

The Pabst Hotel failed within 2 years of launch.

Lawrence Linkman went bankrupt in 1992.

Lehman Brothers went bankrupt in 2008.

There's a few interesting observations in this story.

The Best business went belly-up in 1863.

The NYT went broke in 1896.

The Pabst Hotel failed within 2 years of launch.

Lawrence Linkman went bankrupt in 1992.

Lehman Brothers went bankrupt in 2008.

64/65

Basically, almost every major party that's ever touched this property ended up either broke or nearly so. Add to it the fact that the square has spent a major portion of its life as NYC's seedy underbelly.

Not sure how Ram feels being a marketing prop at a place like that.

Basically, almost every major party that's ever touched this property ended up either broke or nearly so. Add to it the fact that the square has spent a major portion of its life as NYC's seedy underbelly.

Not sure how Ram feels being a marketing prop at a place like that.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter![[THREAD: BAVARIA, BANKRUPTCY, BILLBOARDS]1/65Once upon a time in Bavaria, Germany, lived a man named Jacob Best. There, he ran a small brewery and lived off it with his wife and 4 boys — Phillip, Jacob Jr., Charles, and Lorenz. Bavaria those days was a kingdom. [THREAD: BAVARIA, BANKRUPTCY, BILLBOARDS]1/65Once upon a time in Bavaria, Germany, lived a man named Jacob Best. There, he ran a small brewery and lived off it with his wife and 4 boys — Phillip, Jacob Jr., Charles, and Lorenz. Bavaria those days was a kingdom.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EfbojojUwAAOidw.jpg)