With so many people struggling because of #COVID19, I've been looking at how other people in history dealt with unexpected catastrophes.

There's one in particular that's fascinating.

It involves a famine, a king, and is the type of story we could all use right now.

A thread.

There's one in particular that's fascinating.

It involves a famine, a king, and is the type of story we could all use right now.

A thread.

This is Asaf-ud-Daula. He was the Nawab, or ruler, of Oudh in the 18th century.

Oudh was a princely state in Northern India. Nawabs in general were known to be insanely rich, but especially the Daulas, who were installed by the British.

But everything was about to change.

Oudh was a princely state in Northern India. Nawabs in general were known to be insanely rich, but especially the Daulas, who were installed by the British.

But everything was about to change.

In 1784, the region experienced one of the worst famines in its history. It stretched from Delhi to Punjab.

Tens of thousands lost their jobs. People didn't have enough food to eat.

Some reports say 11 million people were about to die.

So the Nawab came up with a plan.

Tens of thousands lost their jobs. People didn't have enough food to eat.

Some reports say 11 million people were about to die.

So the Nawab came up with a plan.

He decided to build one of the most ambitious construction projects in the world at the time.

It was called the Bara Imambara.

People thought he was crazy to build a massive project in the middle of a famine — but he didn't care.

He had an idea.

He just needed an architect.

It was called the Bara Imambara.

People thought he was crazy to build a massive project in the middle of a famine — but he didn't care.

He had an idea.

He just needed an architect.

The Nawab put out a call, like a modern day Request-for-Proposals

In those days, architects would command a princely sum, like a large plot of land or riches.

India's top architect at the time, a guy named Kifayatullah, offered to do it for free.

He had only one request.

In those days, architects would command a princely sum, like a large plot of land or riches.

India's top architect at the time, a guy named Kifayatullah, offered to do it for free.

He had only one request.

Kifayatullah said that when the building was finished, he wanted to be buried there.

The Nawab agreed, and construction began immediately in the capital, Lucknow. He hired 20,000 workers for the job — all paid for by the royal treasury.

And that's where it gets interesting.

The Nawab agreed, and construction began immediately in the capital, Lucknow. He hired 20,000 workers for the job — all paid for by the royal treasury.

And that's where it gets interesting.

Nearly all of the workers he hired were people who had lost their livelihoods.

The Nawab's goal was to reduce the impact of the famine.

Building the Imambara — and the salary that came with it — literally kept them alive.

But there was a problem.

The Nawab's goal was to reduce the impact of the famine.

Building the Imambara — and the salary that came with it — literally kept them alive.

But there was a problem.

There were so many workers that construction would be finished too quickly.

After that, they'd be jobless again.

On top of that, the noble classes were also suffering. They were better off, but like Covid, famines don't discriminate.

So the Nawab came up with another plan.

After that, they'd be jobless again.

On top of that, the noble classes were also suffering. They were better off, but like Covid, famines don't discriminate.

So the Nawab came up with another plan.

During the day, he paid the laborers to build it.

And at night, he paid nobles to remove part of what the workers had built during the day.

They came at night, in secret, to avoid the shame of publicly admitting they needed money/food.

They were both paid the same.

And at night, he paid nobles to remove part of what the workers had built during the day.

They came at night, in secret, to avoid the shame of publicly admitting they needed money/food.

They were both paid the same.

In the end, a project that would have taken just a few years ended up taking eleven.

It was by design, to feed people, give them dignity, and keep the economy alive — during the greatest famine they'd ever known.

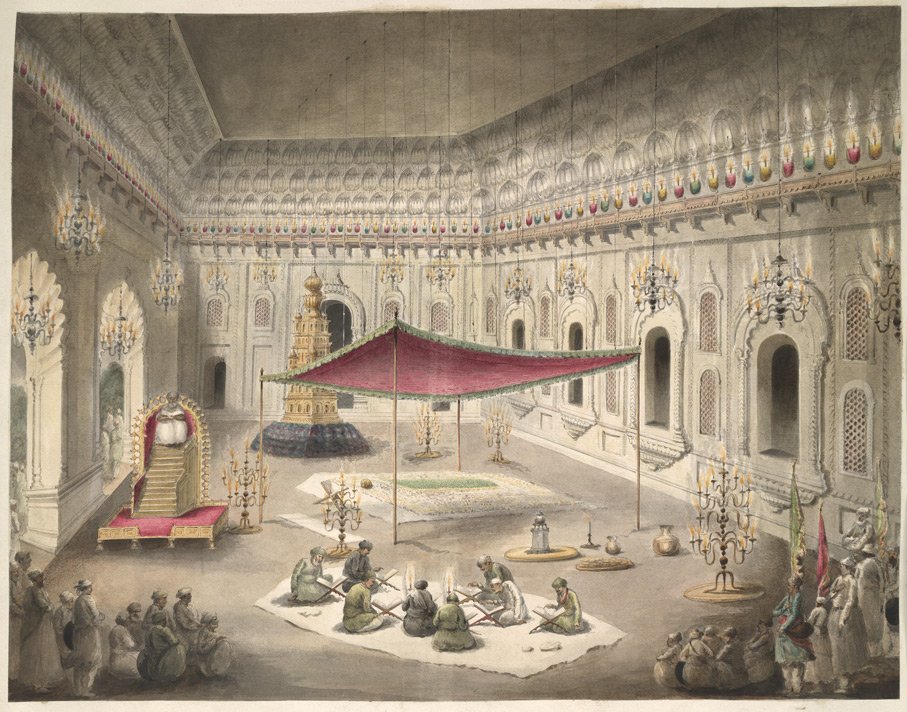

This is what it looked like when it was finished.

It was by design, to feed people, give them dignity, and keep the economy alive — during the greatest famine they'd ever known.

This is what it looked like when it was finished.

It also has a labrynth with a thousand passageways, some leading to nowhere.

There's no consensus on why the labrinth was built, but there's no question it increased the total construction time.

Even today, tourists can't enter it without a guide, for fear of getting lost.

There's no consensus on why the labrinth was built, but there's no question it increased the total construction time.

Even today, tourists can't enter it without a guide, for fear of getting lost.

Today, the Imambara remains a focal point for the city. It's open to everyone, Muslim or not, and home to many religious festivals.

At the end of his life, the Nawab himself asked to be buried there.

In the painting, that's his simple, no frills grave under the canopy.

At the end of his life, the Nawab himself asked to be buried there.

In the painting, that's his simple, no frills grave under the canopy.

History is full of heroes and villains, and things are rarely black/white.

It's also full of moments where people used their power, wealth, or influence to help others.

The question for us is: When we look back at how we dealt with #COVID19, how will history remember us?

End.

It's also full of moments where people used their power, wealth, or influence to help others.

The question for us is: When we look back at how we dealt with #COVID19, how will history remember us?

End.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter