Today, August 9, marks 75 years since the last time nuclear weapons were used in war.

Why have they not been used since?

[THREAD]

Why have they not been used since?

[THREAD]

The literature on the international politics of nuclear weapons is enormous.

For a sense of the overall nuclear politics literature, highly recommend this @AnnualReviews piece by Gartzke & @MatthewKroenig https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-polisci-110113-122130

For a sense of the overall nuclear politics literature, highly recommend this @AnnualReviews piece by Gartzke & @MatthewKroenig https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-polisci-110113-122130

In this thread, I want to focus on just one portion of this literature: the lit exploring the post-1945 non-use of nukes.

Even more specifically, I'll focus on unpacking a prominent explanation for the non-use of nuclear weapons since 1945: "the nuclear taboo"

Even more specifically, I'll focus on unpacking a prominent explanation for the non-use of nuclear weapons since 1945: "the nuclear taboo"

The "taboo" is the claim that there is a global normative prohibition against nuclear weapons (in particular, their first use).

In other words, states avoid using them because it's morally reprehensible to do so.

In other words, states avoid using them because it's morally reprehensible to do so.

Critically, this is not solely a view that civilians shouldn't been targeted in war. That view would explain why large, strategic nuclear weapons have not been used.

Instead, states have also avoided the use of "tactical nuclear weapons", meaning weapons that are "low yield" and only applied on the battlefield.

Moreover, states with nuclear weapons have avoided using them against non-nuclear states. For example, the US dropped the M.O.A.B. conventional bomb in Afghanistan, but not nukes.

That is what is meant by the Taboo: their non-use under any circumstances because using nukes is simply beyond the pale.

How long has this "taboo" been around?

How long has this "taboo" been around?

The notion of Nuclear weapons being morally reprehensible developed rather early, during the Truman administration.

For instance, consider what @NinaTannenwald writes in her 2005 @Journal_IS piece on the origins of the Taboo (link further down in the thread): nukes were almost immediately associated with chemical weapons, which had witnessed a non-use norm during WWII.

@ArmsControlWonk also writes of the early origins of the taboo in this @ForeignPolicy piece (during the 70th anniversary of Hiroshima) https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/08/06/magical-thinking-and-the-real-power-of-hiroshima-nuclear-weapons-japan/

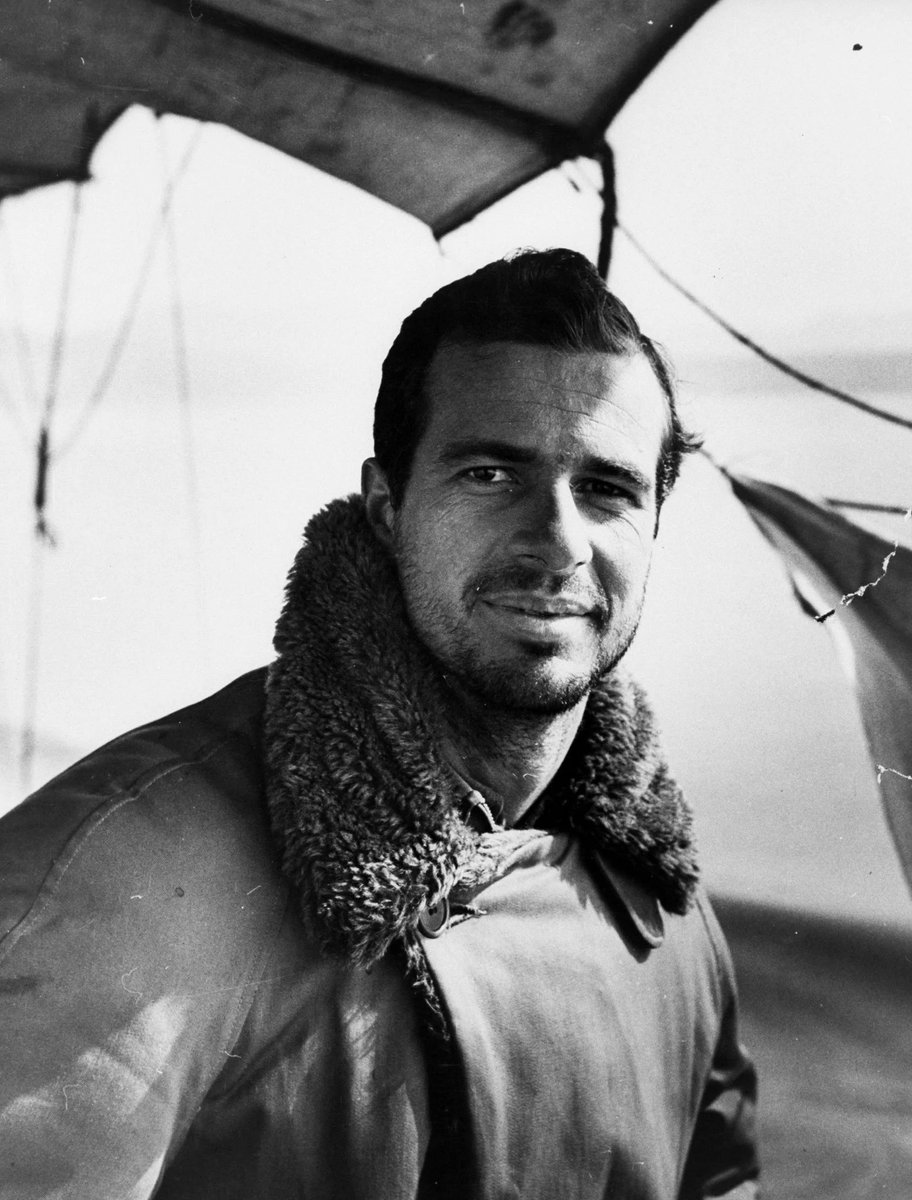

@ArmsControlWonk describes of how the reporting by journalist John Hersey in 1945 brought immediate awareness of the cruel and potentially cataclysmic destruction the bomb could reap

In academic work, the idea of the nuclear taboo began to be explored by the French political philosopher Raymond Aron.

He coined the phrase "atomic taboo" in the 1950s, but a clear statement of the taboo is found in a 1966 piece for a Daedalus.

He writes that "happily, statesmen are paralyzed by the `atomic taboo'". For him, this seems to be a restraint based on the human conscience, but he worries that it is fragile.

In the late 1980s, Janne Nolan discussed how the public perceived nuclear weapons use as a "taboo" subject: political leaders did not want to talk about it because the public doesn't want to think about it.

So the "Taboo" has been around for quite awhile.

But is it responsible for the post-1945 non-use of nuclear weapons?

But is it responsible for the post-1945 non-use of nuclear weapons?

In 1999, @NinaTannenwald systmatized the idea in a highly influential @IntOrgJournal piece. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-organization/article/nuclear-taboo-the-united-states-and-the-normative-basis-of-nuclear-nonuse/EA04E0104A42C12FC785A70F301197CC

She looks for evidence of the Taboo restraining behavior. Specifically, one should see decision makers use "taboo talk": deciding not to use nukes because they are simply "wrong", even in conditions where the material consequences of using them seem limited (or even favorable)

A host of evidence is then brought forward in this piece, further developed in the above mentioned 2005 @Journal_IS piece.... https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/10.1162/isec.2005.29.4.5

...and then in a 2007 book. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Nuclear_Taboo/oTOzgJbf9KkC?hl=en

When Eisenhower became President, he wanted to end the Korean war stalemate. As he wrote in his memoir, "to keep the attack from becoming overly costly, it was clear that we would have to use atomic weapons"

So why didn't they use nukes? Because of the obstacle presented by "this moral problem", as Secretary of State Dulles described it.

Subsequent work has questioned the role of the taboo.

@tvpaul1 in @RISjnl discusses the role of "tradition", meaning a long standing precedent exists of avoiding their use, but there is nothing morally constraining a change in that behavior. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/review-of-international-studies/article/taboo-or-tradition-the-nonuse-of-nuclear-weapons-in-world-politics/5E1209073DA91E8574E7B72721590037

Furthermore, Press, Sagan, and Valentino in @apsrjournal use survey experiments to show that the public is not opposed to the use of nuclear weapons, even first use. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/atomic-aversion-experimental-evidence-on-taboos-traditions-and-the-nonuse-of-nuclear-weapons/3F9FD4E39E19284555376D01AA36028E

Indeed, Sagan and Valentino expand this study by focusing specifically on the possible use of nuclear weapons against Iran

https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/ISEC_a_00284

https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/ISEC_a_00284

And if nuclear weapon use were "taboo", then the US nuclear doctrine would probably not rely on "Launch on warning", as soberly described by @RadioFreeTom in this thread https://twitter.com/RadioFreeTom/status/1157447390481321988

Moreover, the decision making process for the US to launch its own nukes wouldn't been so prone to accident, as illustrated by this @NTI_WMD timeline

https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/launch-under-attack-feasible/

https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/launch-under-attack-feasible/

Debate over the "nuclear taboo" is just one element of the larger literature on nuclear politics. But it's an important element, as it sheds light on why Nagasaki witnessed (hopefully) the final use of nuclear weapons in war.

[END]

[END]

Addendum: important to also read Thomas Schelling's views on non-use, particularly his Nobel prize piece (which is why he could have won the prize for BOTH peace and economics). h/t @NinaTannenwald https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2005/schelling/lecture/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter![Today, August 9, marks 75 years since the last time nuclear weapons were used in war.Why have they not been used since? [THREAD] Today, August 9, marks 75 years since the last time nuclear weapons were used in war.Why have they not been used since? [THREAD]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ee-d81CX0AAkYmL.jpg)