Have been trying to stay out of the Sean Wilentz/Tom Cotton debate about the supposedly antislavery potential of the Constitution, but a ton of people have emailed me this week so (deep breath) here are some thoughts on Wilentz's piece in @NYRDaily. https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2020/08/03/what-tom-cotton-gets-so-wrong-about-slavery-and-the-constitution/

Wilentz is queasy after Tom Cotton claimed him as an ally in the fight against the #1619Project and “radical historical revisionism” which seeks to argue that America was “founded on racism.” https://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2020/07/30/sen_cotton_the_1619_project_a_radical_work_of_historical_revisionism_that_aims_to_indoctrinate_kids.html

You can see why Cotton would think Wilentz was a fellow traveller. Cotton insists that America was founded “on the natural equality of mankind and the freedom that flows from that”; SW argues that the Constitution “contained powerful antislavery potential.”

I won’t rehearse my arguments with SW, which were laid out in the pages of the NYR last year. I’ll just say three things about the entirely predictable fact that Tom Cotton would invoke Wilentz in his false and creepy recasting of the Founding. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2019/06/06/how-proslavery-was-the-constitution/

First, any attempt to argue for the “antislavery potential” of a document which allowed for the massive expansion of slavery is always going to seem speculative, and has the potential to offend both the facts and many of your fellow Americans.

Although SW denies Cotton's “necessary evil” formulation, SW's thesis isn't that far away from it: the Founders wanted to limit slavery’s power but couldn’t do more than they did. The Constitution didn’t ‘enshrine’ slavery everywhere, forever; Lincoln et al. did the rest.

As I noted in my review of SW's book last year, it's certainly possible that the United States could have been EVEN MORE proslavery; though that doesn't change the fact that it was still pretty darned proslavery for nearly a century.

This passage of Wilentz’s argument presents a more nuanced view; and it was ‘antislavery slaveholders’ like Jefferson and Madison as well as Northerners who were complicit in the massive expansion of slavery DESPITE the Constitution.

Second, the argument for “antislavery potential” rehashes the old narrative of racial liberalism: the US always nurtures a seed of equality which eventually flowers for everyone. This idea of linear progress on race is more precious to white liberals even than their Dylan vinyl

IMO it profoundly misunderstands the deep structural continuities of racism in American history; it offers a comforting vision that America will realise its ideals when the time is right, at which point equality catches up with everyone.

Which brings me to the third thing: SW’s thesis is grounded in James Madison intoning the principle of “no property in man" at Philadelphia in 1787, which btw he may not even have said in the Constitutional Convention.

The idea that MADISON — sainted Madison! — watered the antislavery seed does a lot of work for SW, and suggests that we can keep the pantheon of Founding heroes we used to enjoy before the radical revisionists showed up with their cancel-clubs

Let’s assume for a second (big assumption) that Madison did declaim on the principle of “no property in man” at Philadelphia in 1787. Here’s the thing you need to know about Madison: his shimmering antislavery was always yoked to his plans to remove Black people from the US.

I wrote a whole book about this but confess I am still stunned by how many intellectuals (and even historians) assume that antislavery sentiments necessarily involve a commitment to racial equality.

Don’t get me wrong, it is awesome that Jefferson and Madison wrote often (though mostly privately) that slavery was bad. Would have been great if they’d devised a single emancipation scheme during their sixteen years in the White House, but the sentiment is something.

BUT both TJ and Madison were consistent and even stubborn advocates of ‘colonization’ across most of their adult lives. They always insisted that ending slavery could only be secured by exiling Black people from the US.

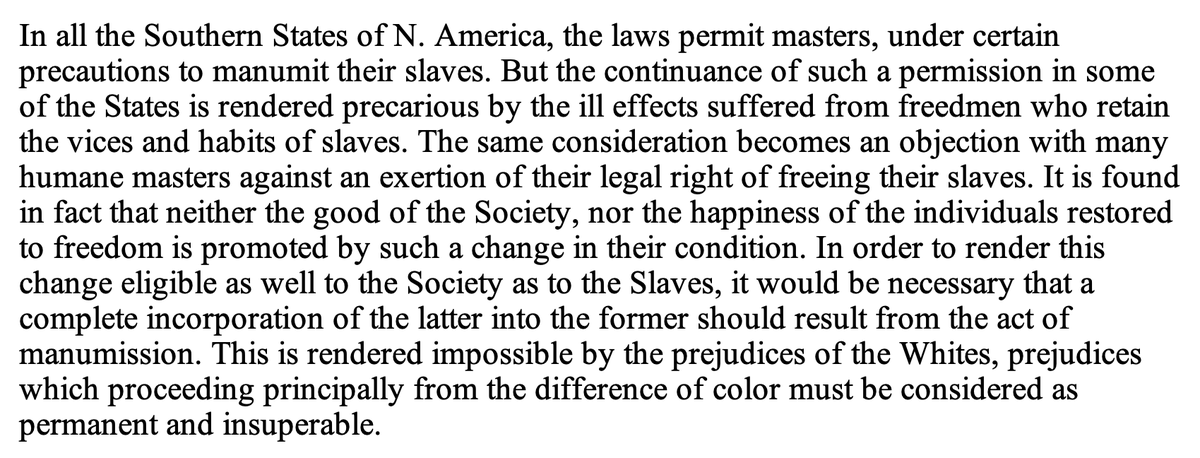

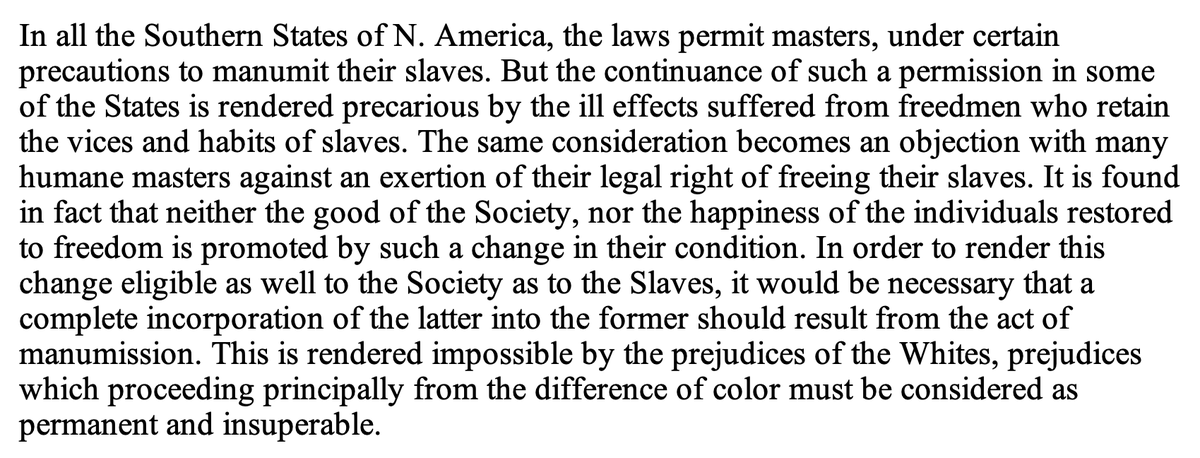

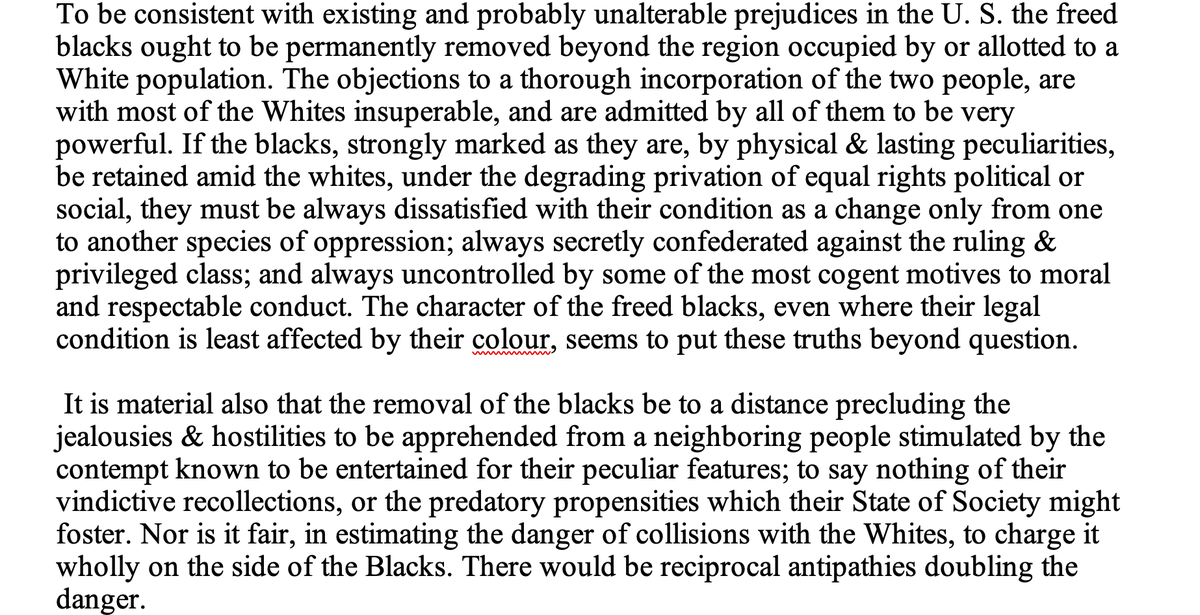

Here’s Madison in 1819, after his two terms in the White House. You can see that blaming _other white people’s prejudices_ for the necessity of removing Black people is a real mood for him.

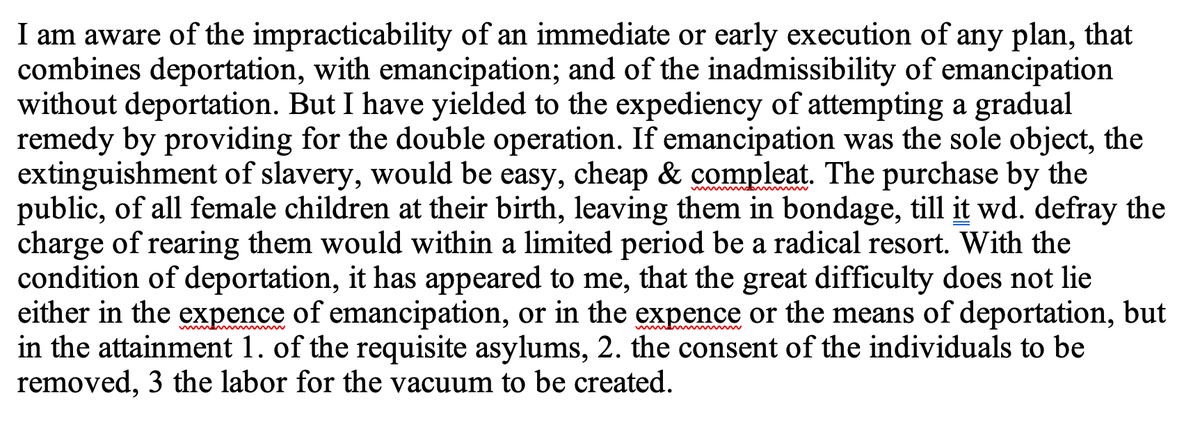

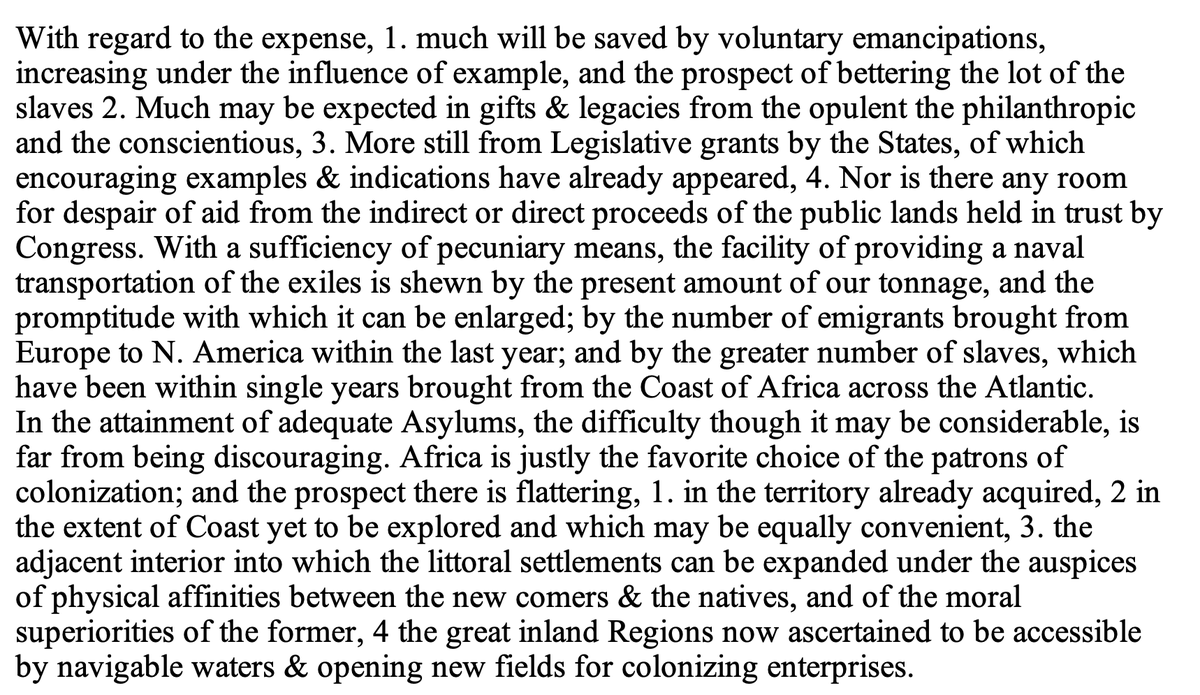

And Madison in 1833 writing to Thomas Dew — who, incidentally, was the Southern intellectual who became known as an architect of the ‘necessary evil’ thesis about slavery.

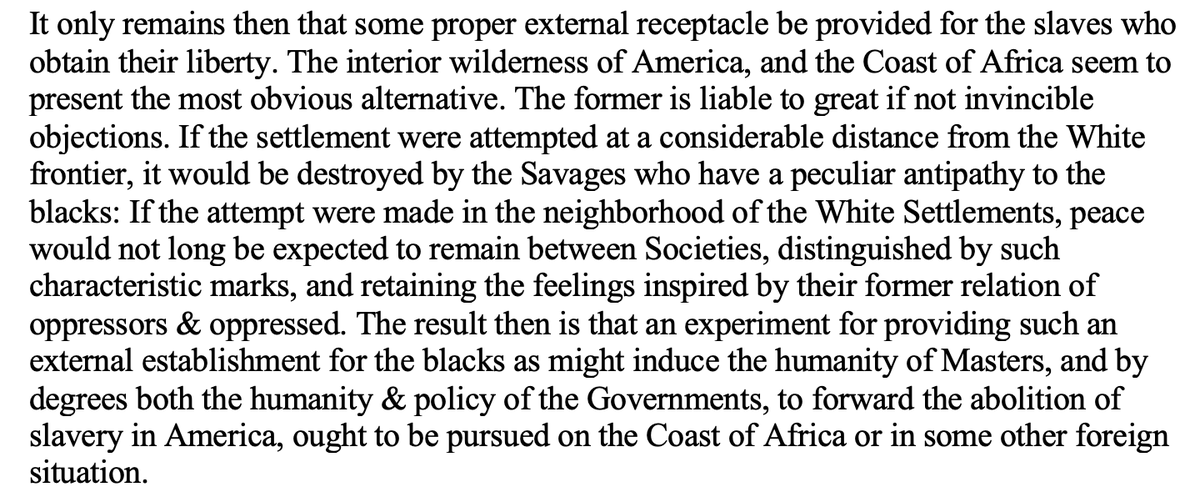

Madison thought that the money to finance Black removal could come from selling off lands the government acquired from Native Americans in the West; as with the expansion of slavery, the racial oppression of Black and Indigenous people was invariably entangled.

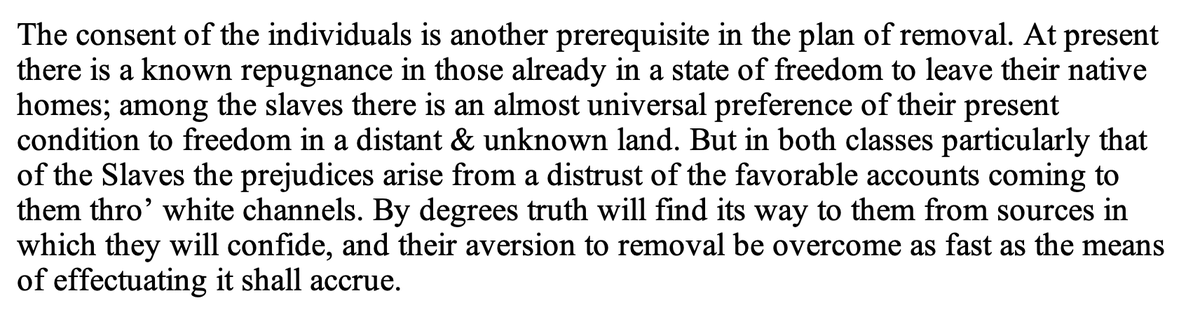

And here (same 1833 letter to Dew) Madison acknowledges Black opposition — even opposition from enslaved people! — to leaving the US, but reassures Dew that African Americans will cheerfully embrace exile when it’s put them without, uh, prejudice.

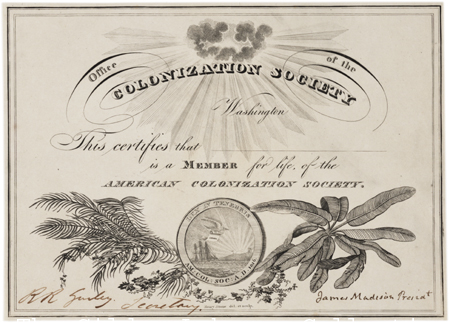

Soon after writing to Dew, James Madison became president of the American Colonization Society, the leading organisation promoting Black removal from the US, a position he held until his death in 1836. IMO we don't think about this enough.

If you want to talk about Madison endorsing ‘no property in man’, you also need to own Madison’s prerequisite for ending slavery: the denial of Black belonging in the United States. Black exclusion was the sine qua non of “no property in man” for Madison and SO many others.

And here’s a final irony: Madison was writing to Thomas Dew to persuade him that colonization still had a chance, even though Black people thought it was a terrible idea and many whites (including Dew) had begun to see it as impracticable.

Because Madison et al had made colonization a condition of antislavery, the apparent impossibility of removing the entire Black population actually allowed Dew to argue that slavery was a necessary evil!

I appreciate that SW is not happy that Tom Cotton has cosied up to him on the subject of race & the Founding, but it was always predictable that right and even far-right voices would stan Wilentz for his attacks on #1619 and his defence of the old racial liberalism narrative.

We don’t have to ‘cancel’ the Founders (whatever that means) or deny the presence of antislavery _and_ proslavery voices in early US history; but we do need to recognise that racial exclusion was baked into the nation from the very beginning./

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter