[THREAD: HIBAKUSHA]

1/61

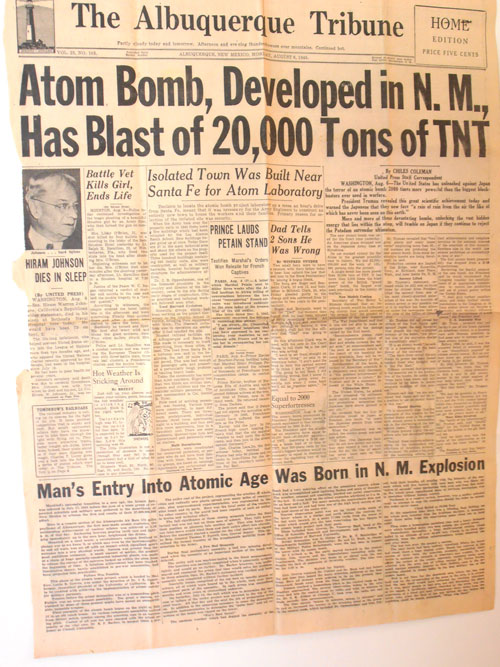

At about 8:15 AM on August 6, 1945, a Boeing Superfortress dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima and instantly vaporized, by conservative estimates, 30% of the city's human population.

This was the least tragic thing that happened to Japan that day.

1/61

At about 8:15 AM on August 6, 1945, a Boeing Superfortress dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima and instantly vaporized, by conservative estimates, 30% of the city's human population.

This was the least tragic thing that happened to Japan that day.

2/61

Little Boy was the world's first nuclear weapon, one of only 2 till date, to be used in war. It was also breathtakingly inefficient. Although it managed to kill almost 80k in the blink of an eye, it did so with over 98% of its fissile material going unused.

Little Boy was the world's first nuclear weapon, one of only 2 till date, to be used in war. It was also breathtakingly inefficient. Although it managed to kill almost 80k in the blink of an eye, it did so with over 98% of its fissile material going unused.

3/61

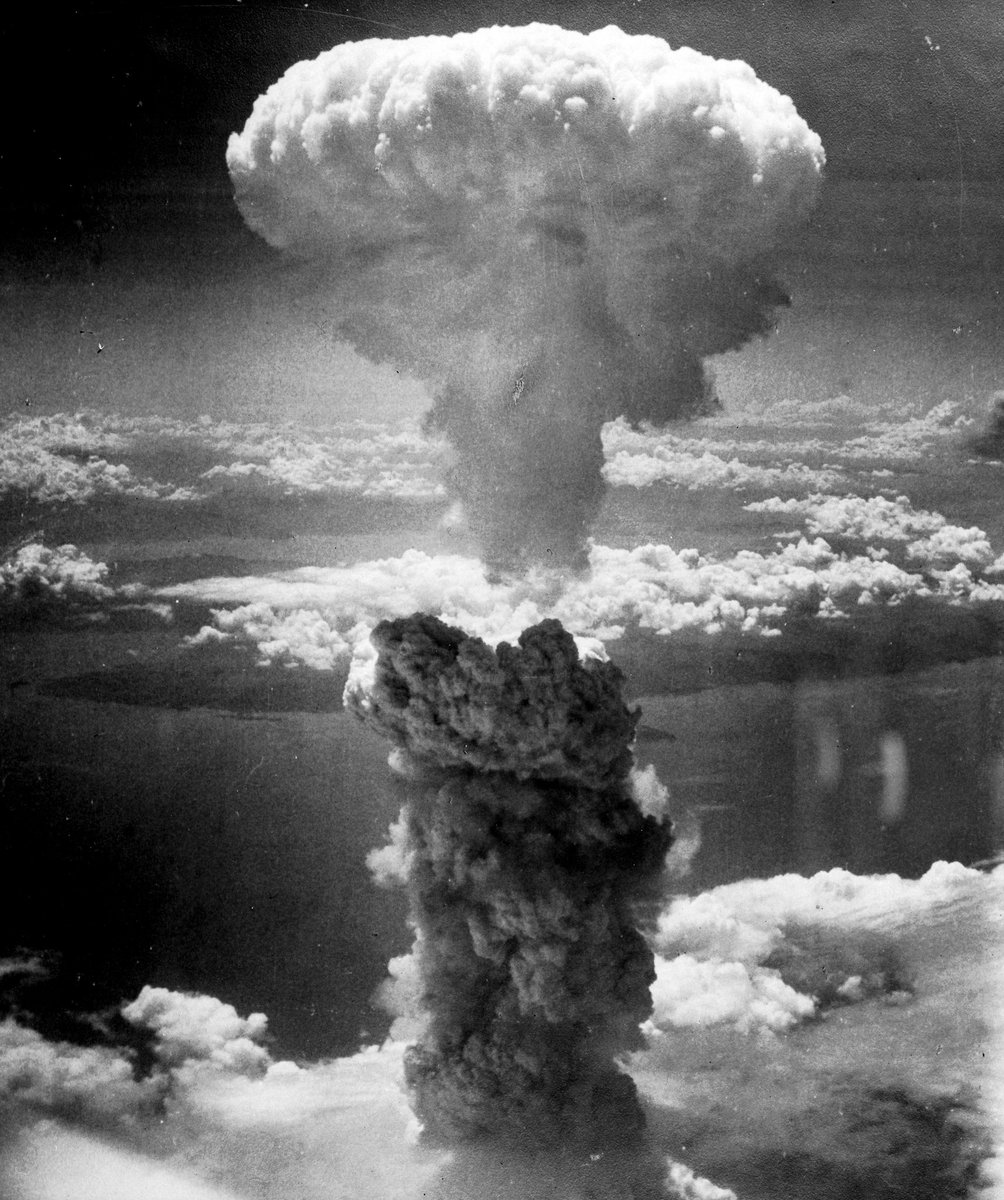

Little Boy's yield is estimated at about 15 kilotons, a good 7 kilotons short of the Trinity test from 3 weeks earlier. That test was the first ever, one that made Oppenheimer quote the Gita:

"I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

Little Boy's yield is estimated at about 15 kilotons, a good 7 kilotons short of the Trinity test from 3 weeks earlier. That test was the first ever, one that made Oppenheimer quote the Gita:

"I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

4/61

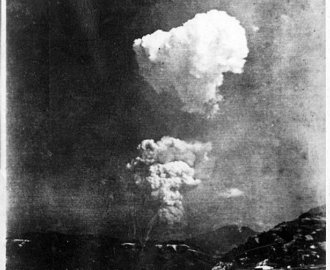

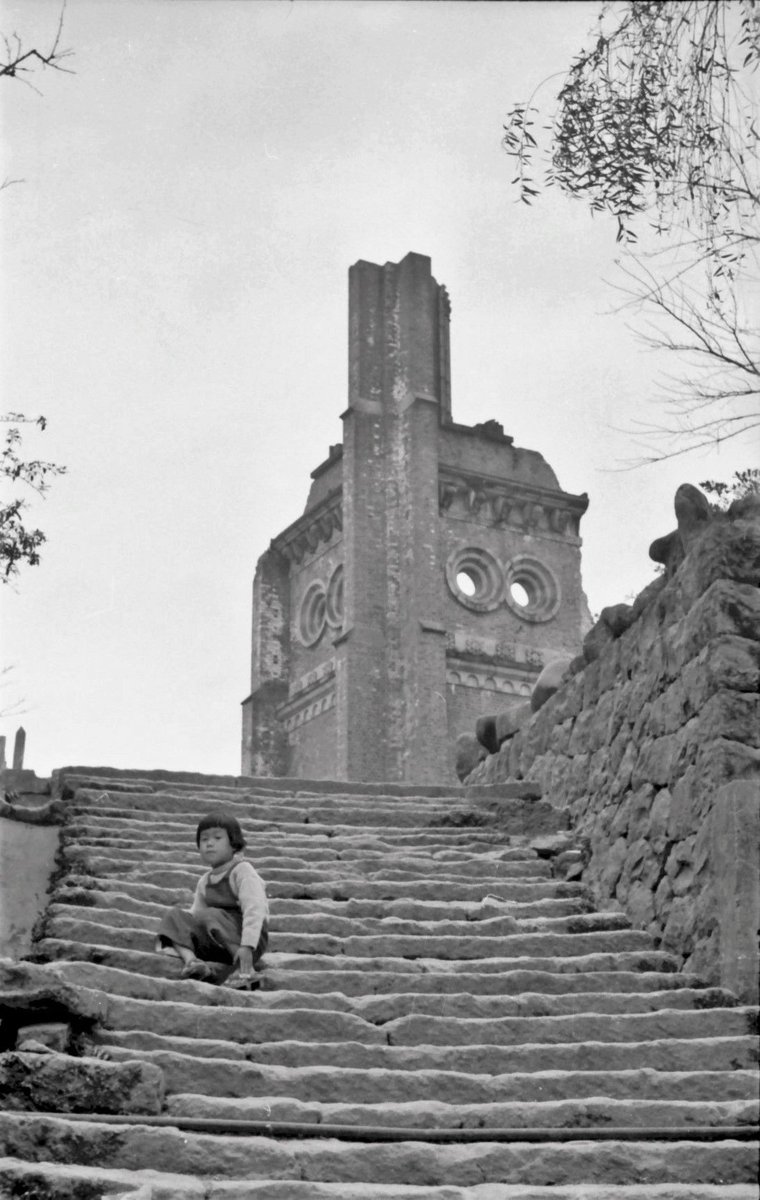

But this one isn't about the big boom that day. Much has already been written detailing, in great gory elaboration, every feature thereof — from mushroom cloud to shockwave to hitokage no ishi to black rain. This one isn't about those. This one's about what followed.

But this one isn't about the big boom that day. Much has already been written detailing, in great gory elaboration, every feature thereof — from mushroom cloud to shockwave to hitokage no ishi to black rain. This one isn't about those. This one's about what followed.

5/61

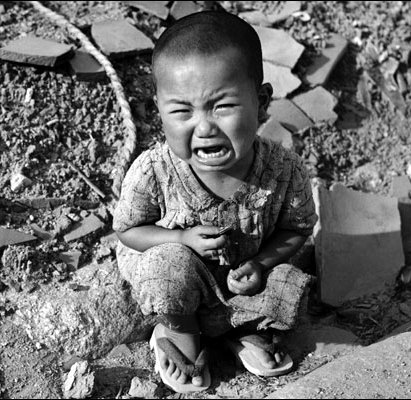

Death wasn't swift for all that day. Many of the 70% who survived had a life of excruciating pain ahead of them. This pain was physical and emotional, and understandably so, but it was also social. The bomb changed Japan, not just physically but also socially.

Death wasn't swift for all that day. Many of the 70% who survived had a life of excruciating pain ahead of them. This pain was physical and emotional, and understandably so, but it was also social. The bomb changed Japan, not just physically but also socially.

6/61

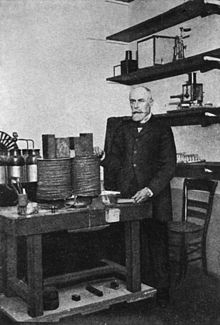

Radiation sickness wasn't a thoroughly understood demon back then although 1945 came a good 37 years after Antoine Henri Becquerel became the first big ticket loss to the mysterious death rays. Ignorance inspires fear. And fear inspires stigma. See where this is going?

Radiation sickness wasn't a thoroughly understood demon back then although 1945 came a good 37 years after Antoine Henri Becquerel became the first big ticket loss to the mysterious death rays. Ignorance inspires fear. And fear inspires stigma. See where this is going?

7/61

The Japanese are a strange lot. They hold their dead in a certain esteem, just like most other cultures. But they accord the same esteem to death itself as well. The Grim Reaper is sacred. Not to be insulted.

And that's why the term "survivor" was problematic.

The Japanese are a strange lot. They hold their dead in a certain esteem, just like most other cultures. But they accord the same esteem to death itself as well. The Grim Reaper is sacred. Not to be insulted.

And that's why the term "survivor" was problematic.

8/61

The term's primacy on being alive is an affront to the dead. So they came up with an alternative.

You were not a survivor. You were a person affected by the explosion.

You were a hibakusha (被爆者).

Hi = affected

Baku = bomb

Sha = person

Hibakusha.

The term's primacy on being alive is an affront to the dead. So they came up with an alternative.

You were not a survivor. You were a person affected by the explosion.

You were a hibakusha (被爆者).

Hi = affected

Baku = bomb

Sha = person

Hibakusha.

9/61

The political correctness didn't help the stigma though. It was like the HIV. If you had it, you were an outcast. An untouchable.

Nobody wanted to "contract" whatever you might be carrying.

So if you happened to be in Hiroshima that day, and lived, you were cursed.

The political correctness didn't help the stigma though. It was like the HIV. If you had it, you were an outcast. An untouchable.

Nobody wanted to "contract" whatever you might be carrying.

So if you happened to be in Hiroshima that day, and lived, you were cursed.

10/61

For a good 9 years, the government didn't even acknowledge their existence. Admitting the living breathing horrors of the nuclear bombing would mean opening itself to moral responsibilities for the triggers. Nanking, Pearl Harbor, Philippines...it'd get messy.

For a good 9 years, the government didn't even acknowledge their existence. Admitting the living breathing horrors of the nuclear bombing would mean opening itself to moral responsibilities for the triggers. Nanking, Pearl Harbor, Philippines...it'd get messy.

11/61

Dō-oh Mineko was a boisterous 11 year old raised in a traditional Japanese family with conservative values and ample fear of God. 11 year old in 1941, that is. That's when, one cold December morning, she experienced the beginning of change.

Dō-oh Mineko was a boisterous 11 year old raised in a traditional Japanese family with conservative values and ample fear of God. 11 year old in 1941, that is. That's when, one cold December morning, she experienced the beginning of change.

12/61

Gathered in the assembly hall, the students at Inasa Elementary bowed to the emperor's portrait and awaited as the principal began his address. The school was not far from where Dō-oh lived on Mount Inasa, just outside Nagasaki. Her father worked at Mitsubishi in the city.

Gathered in the assembly hall, the students at Inasa Elementary bowed to the emperor's portrait and awaited as the principal began his address. The school was not far from where Dō-oh lived on Mount Inasa, just outside Nagasaki. Her father worked at Mitsubishi in the city.

13/61

The address was solemn but not alarming. The principal knew better than to trigger panic amongst his pupils. But he did drop the one piece of dread wrapped in reassurance: Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor the previous day.

And that they were at war with the Americans now.

The address was solemn but not alarming. The principal knew better than to trigger panic amongst his pupils. But he did drop the one piece of dread wrapped in reassurance: Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor the previous day.

And that they were at war with the Americans now.

14/61

Dō-oh was too young to fully grasp the extent of what it meant, but there was little illusion in her mind that this wasn't a positive development. The following year, the Minekos evacuated to a rural area further inland and Dō-oh joined the local Keiho Girls' High.

Dō-oh was too young to fully grasp the extent of what it meant, but there was little illusion in her mind that this wasn't a positive development. The following year, the Minekos evacuated to a rural area further inland and Dō-oh joined the local Keiho Girls' High.

15/61

When I say local, I mean a 2-hour walk from her place. Initially Dō-oh learned the usual — ikebana (flower arrangement), sadō (tea ceremony), koto (a stringed instrument), etc. But after the first year, things started getting more...militaristic.

When I say local, I mean a 2-hour walk from her place. Initially Dō-oh learned the usual — ikebana (flower arrangement), sadō (tea ceremony), koto (a stringed instrument), etc. But after the first year, things started getting more...militaristic.

16/61

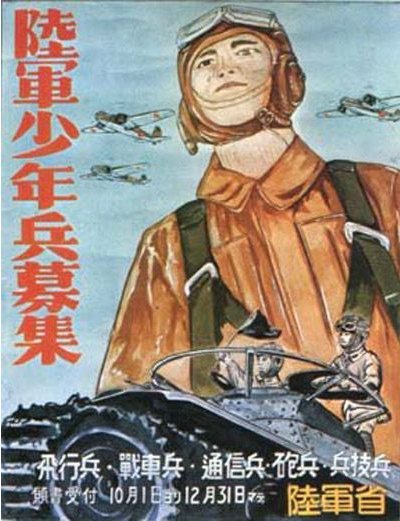

Each morning, Dō-oh and her classmates would recite the Imperial Rescript of Education, pledging unconditional loyalty to the emperor and "God's chosen country." The pledge also included "courageously offering themselves to the State" should the need arise.

Each morning, Dō-oh and her classmates would recite the Imperial Rescript of Education, pledging unconditional loyalty to the emperor and "God's chosen country." The pledge also included "courageously offering themselves to the State" should the need arise.

17/61

Like her friends, Dō-oh would fantasize getting married to a soldier eventually. The imperial government had meticulously cultivated an aura of elite divinity around its soldiers. Laying your life for the State was a matter of highest possible prestige.

Like her friends, Dō-oh would fantasize getting married to a soldier eventually. The imperial government had meticulously cultivated an aura of elite divinity around its soldiers. Laying your life for the State was a matter of highest possible prestige.

18/61

Sometime that year, Dō-oh's 23-year-old brother, her eldest, received a "red paper." He was being conscripted. He was to immediately prepare his last will and testament, seal it along with fingernail and hair clippings in an envelope, and leave home.

He would never return.

Sometime that year, Dō-oh's 23-year-old brother, her eldest, received a "red paper." He was being conscripted. He was to immediately prepare his last will and testament, seal it along with fingernail and hair clippings in an envelope, and leave home.

He would never return.

19/61

The aerial-launched torpedoes used in the Park Harbor mission were built by Mitsubishi at the Ōhashi plant of their arms factory. Today, it's the Nagasaki University Bunkyo area campus.

In 1944, Dō-oh, like her friends, was abruptly taken off school and sent to work here.

The aerial-launched torpedoes used in the Park Harbor mission were built by Mitsubishi at the Ōhashi plant of their arms factory. Today, it's the Nagasaki University Bunkyo area campus.

In 1944, Dō-oh, like her friends, was abruptly taken off school and sent to work here.

20/61

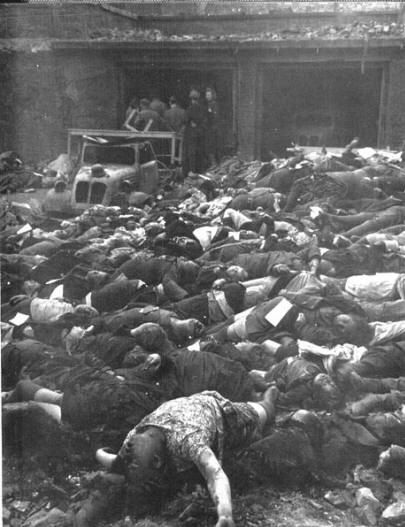

Sometime in March, 1945, in order to break Japanese morale, the Americans launched a wave of carpetbombing campaigns across the country starting with Operation Meetinghouse in Tokyo. These campaigns would claim many more lives than even the nukes.

Sometime in March, 1945, in order to break Japanese morale, the Americans launched a wave of carpetbombing campaigns across the country starting with Operation Meetinghouse in Tokyo. These campaigns would claim many more lives than even the nukes.

21/61

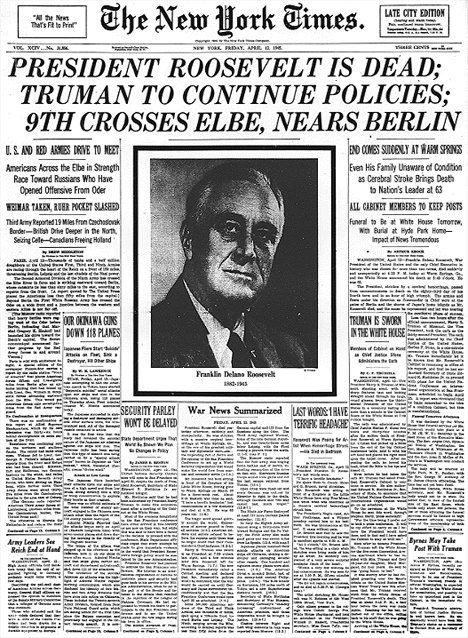

On April 12, less than 3 months into his 4th term, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, died of a hemorrhage. He was succeeded by a WW1 vet named Harry S Truman. It'd take Truman another 2 weeks before he even learns about the Manhattan Project. Even Stalin knew before him.

On April 12, less than 3 months into his 4th term, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, died of a hemorrhage. He was succeeded by a WW1 vet named Harry S Truman. It'd take Truman another 2 weeks before he even learns about the Manhattan Project. Even Stalin knew before him.

22/61

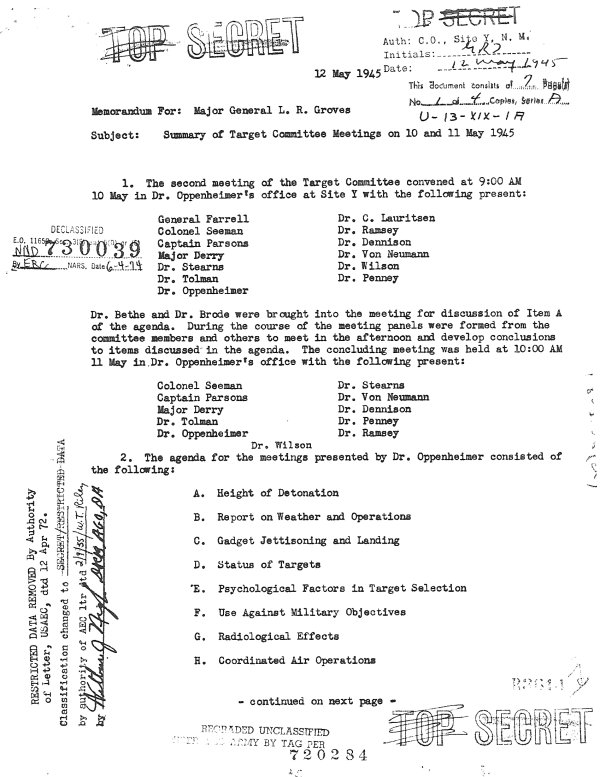

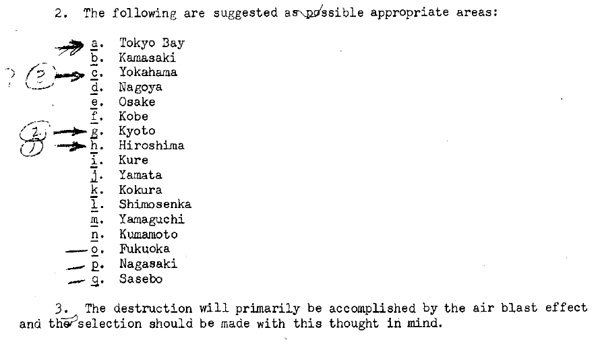

By summer, the US military's Target Committee had drawn an eligibility criteria for the soon-to-be-ready nukes. The bombs' steep $2b price tag demanded maximum bang for the buck, no pun intended. Peak psychological effect was the endgame, the boom had to be "spectacular."

By summer, the US military's Target Committee had drawn an eligibility criteria for the soon-to-be-ready nukes. The bombs' steep $2b price tag demanded maximum bang for the buck, no pun intended. Peak psychological effect was the endgame, the boom had to be "spectacular."

23/61

The criteria were:

1. Located within 1,500 miles from the Pacific airbase (that was a B-29's flight range)

2. At least 3 miles in diameter

3. Arms factory nearby

4. Clear weather

17 cities qualified.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki (second last on the list) made the list.

The criteria were:

1. Located within 1,500 miles from the Pacific airbase (that was a B-29's flight range)

2. At least 3 miles in diameter

3. Arms factory nearby

4. Clear weather

17 cities qualified.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki (second last on the list) made the list.

24/61

"Enemy Drops New-Type Bomb on Hiroshima — Considerable Damage Done," read a Japanese newspaper headline on Aug 8. Nobody in Nagasaki knew they had less than 24 hours left, but alarmed they were. Survivors from Hiroshima had already started seeping into the city.

"Enemy Drops New-Type Bomb on Hiroshima — Considerable Damage Done," read a Japanese newspaper headline on Aug 8. Nobody in Nagasaki knew they had less than 24 hours left, but alarmed they were. Survivors from Hiroshima had already started seeping into the city.

25/61

One such survivor was Tsuno-o Susumu, president of Nagasaki Medical College, who passed Hiroshima on his homebound train ride from Tokyo the previous night. He described "a great flash" and a "violent blast," too big for any bomb shelter in Nagasaki.

One such survivor was Tsuno-o Susumu, president of Nagasaki Medical College, who passed Hiroshima on his homebound train ride from Tokyo the previous night. He described "a great flash" and a "violent blast," too big for any bomb shelter in Nagasaki.

26/61

Assuming there was still time, Governor Nagano invited city administration and police for an evacuation huddle the next morning. His calls went well into the night. Some 1,600 miles away from this commotion, a large cylinder awaited lifting in a concrete pit in Guam.

Assuming there was still time, Governor Nagano invited city administration and police for an evacuation huddle the next morning. His calls went well into the night. Some 1,600 miles away from this commotion, a large cylinder awaited lifting in a concrete pit in Guam.

27/61

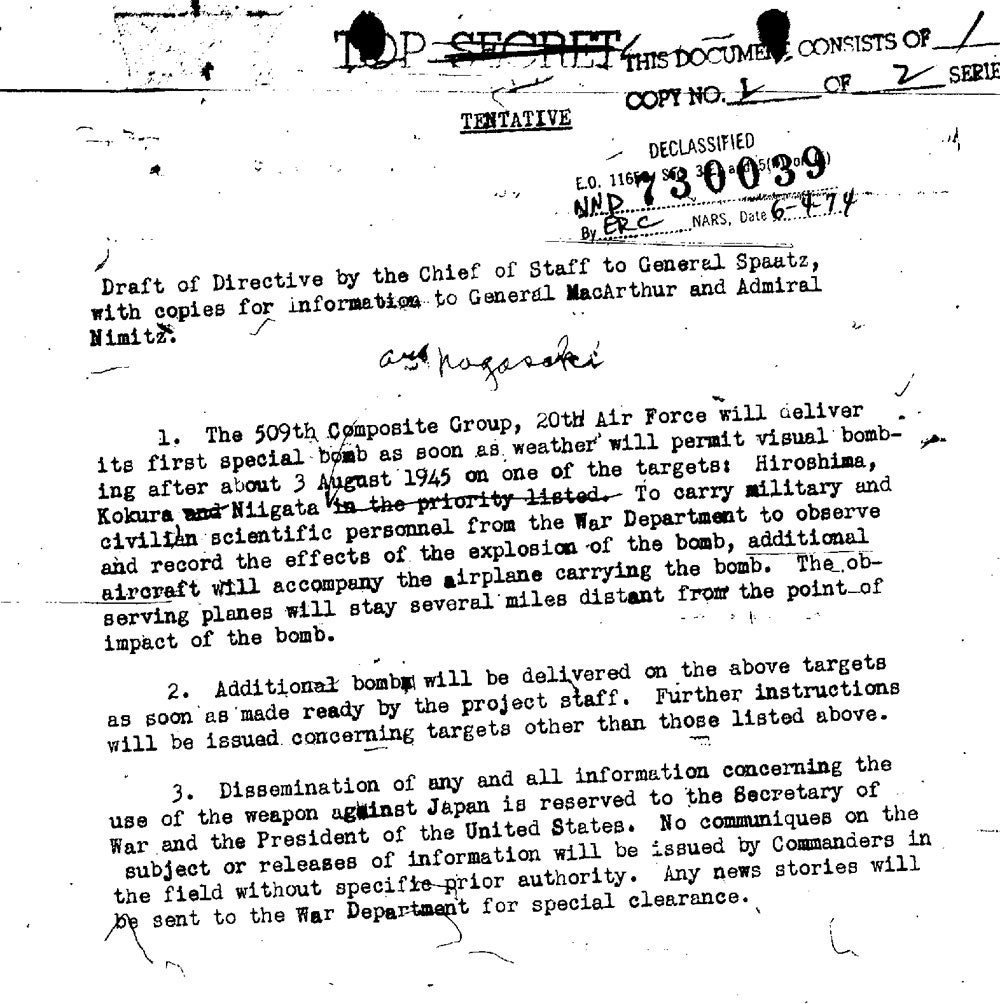

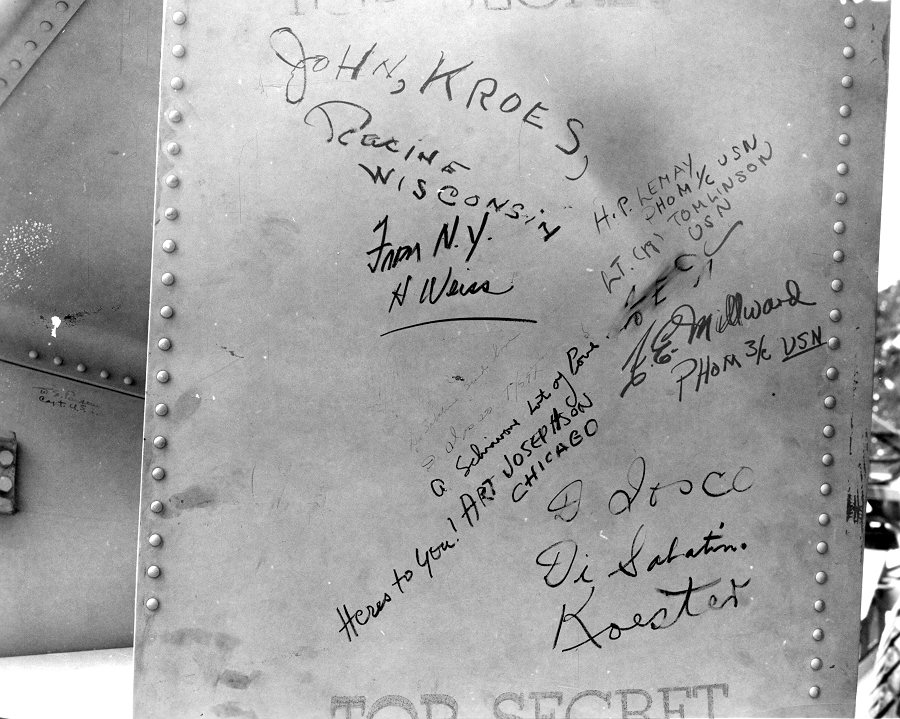

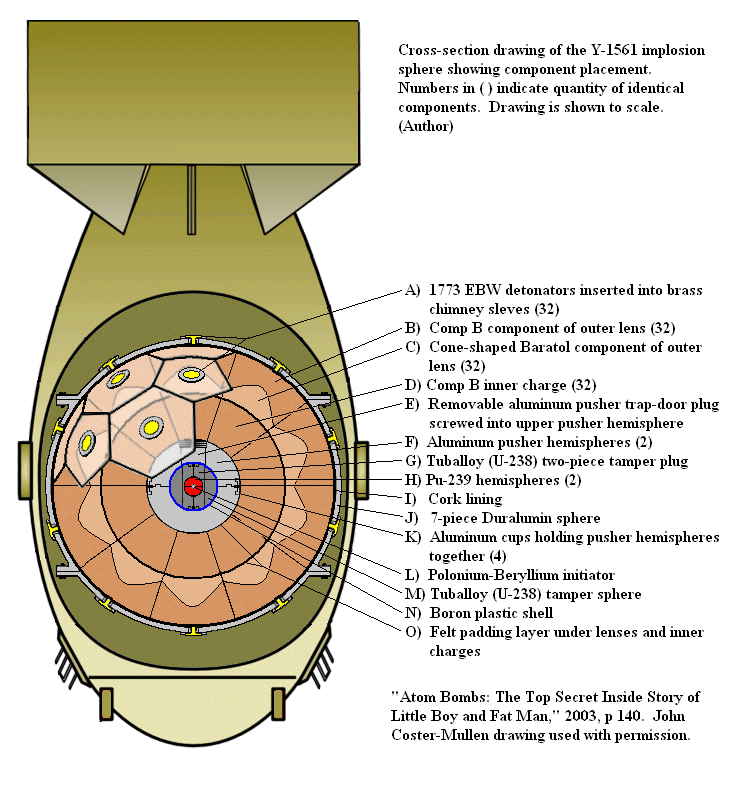

Some 10 feet in length and half as much in diameter, the stout barrel weighed over 10k pounds and had, among other things, "Here's to you!" written on its side. Deep inside, it housed about 13 pounds of enriched plutonium-239 ringed by 64 timed explosives.

Some 10 feet in length and half as much in diameter, the stout barrel weighed over 10k pounds and had, among other things, "Here's to you!" written on its side. Deep inside, it housed about 13 pounds of enriched plutonium-239 ringed by 64 timed explosives.

28/61

The whole contraption looked like a fat man. So they called it Fat Man. By midnight, the bomb had moved out of its concrete pit and into its designated bay aboard a B-29 named Bockscar.

Nagasaki barely slept that night, but the following morning was impressively routine.

The whole contraption looked like a fat man. So they called it Fat Man. By midnight, the bomb had moved out of its concrete pit and into its designated bay aboard a B-29 named Bockscar.

Nagasaki barely slept that night, but the following morning was impressively routine.

29/61

Alarm raids that had started 11:00 PM the previous night continued to blare well into daybreak. Those who could, scurried into any available bomb shelter in the city. Some evacuated to the Urakami Valley across the mountains. By 11:00 AM things were closer to normal.

Alarm raids that had started 11:00 PM the previous night continued to blare well into daybreak. Those who could, scurried into any available bomb shelter in the city. Some evacuated to the Urakami Valley across the mountains. By 11:00 AM things were closer to normal.

30/61

There had been some visitors from Hiroshima too. One man had lost his home the previous day and found his wife's bones under the debris. He had taken a train ride to Nagasaki and was now wandering the city streets with a wash-basin full of his wife's ashes.

There had been some visitors from Hiroshima too. One man had lost his home the previous day and found his wife's bones under the debris. He had taken a train ride to Nagasaki and was now wandering the city streets with a wash-basin full of his wife's ashes.

31/61

Governor Nagano had begun his meeting with city officials at a concrete shelter near Suwa Shrine. Six miles above, the sky was lined with clouds. Above them, whirred Bockscar and its 2 companions. The clouds kept the radars dangerously unaware of the death above.

Governor Nagano had begun his meeting with city officials at a concrete shelter near Suwa Shrine. Six miles above, the sky was lined with clouds. Above them, whirred Bockscar and its 2 companions. The clouds kept the radars dangerously unaware of the death above.

32/61

Aboard the B-29, Major Sweeny was in trouble. His orders were clear. The bomb must only be dropped only after a clear visual confirmation of the target, the old city center.

But there were clouds.

So a visual confirmation called for multiple passes over the city.

Aboard the B-29, Major Sweeny was in trouble. His orders were clear. The bomb must only be dropped only after a clear visual confirmation of the target, the old city center.

But there were clouds.

So a visual confirmation called for multiple passes over the city.

33/61

Multiple passes call for more fuel. But Bockscar now had only enough accessible fuel left for one pass and an emergency landing at the American airbase in Okinawa. There was another problem. Those 64 timed explosives around the bomb's plutonium core. Remember those?

Multiple passes call for more fuel. But Bockscar now had only enough accessible fuel left for one pass and an emergency landing at the American airbase in Okinawa. There was another problem. Those 64 timed explosives around the bomb's plutonium core. Remember those?

34/61

They were timed. And armed. The only option was to drop the bomb in the ocean if they were to avoid an explosion on their way back to Okinawa.

Nagasaki almost survived that day.

Then something happened.

A crack in the clouds.

They were timed. And armed. The only option was to drop the bomb in the ocean if they were to avoid an explosion on their way back to Okinawa.

Nagasaki almost survived that day.

Then something happened.

A crack in the clouds.

35/61

"I've got it! I've got it!"

That was Captain Kermit Beahan the mission's bombardier. He had made a visual confirmation of Nagasaki through a momentary crack in the cloud cover. Within seconds, a lever was pulled and Fat Man was on its way to the doomed city below.

"I've got it! I've got it!"

That was Captain Kermit Beahan the mission's bombardier. He had made a visual confirmation of Nagasaki through a momentary crack in the cloud cover. Within seconds, a lever was pulled and Fat Man was on its way to the doomed city below.

36/61

By 11:03 AM Nagasaki was a post-apocalyptic wasteland that smelled of ozone, metal, and death. Dō-oh, who was at the factory awaiting lunch break, suddenly found herself under an ungodly amount of concrete and steel. She had no idea what just happened.

By 11:03 AM Nagasaki was a post-apocalyptic wasteland that smelled of ozone, metal, and death. Dō-oh, who was at the factory awaiting lunch break, suddenly found herself under an ungodly amount of concrete and steel. She had no idea what just happened.

37/61

Rescue operations began in earnest and eventually, Nagasaki was on its path to recovery. Japan officially announced surrender 6 days later and the most destructive war of all times finally came to an end.

And thus began a new odyssey of ordeal for the survivors.

Rescue operations began in earnest and eventually, Nagasaki was on its path to recovery. Japan officially announced surrender 6 days later and the most destructive war of all times finally came to an end.

And thus began a new odyssey of ordeal for the survivors.

38/61

Dō-oh had glass splinters that wouldn't leave her body for the rest of her life. Her life, from here on, was a profile in what's now called Acute Radiation Syndrome or ARS. First came the hair-loss, then the internal bleeding. The fatigue she experienced never really left.

Dō-oh had glass splinters that wouldn't leave her body for the rest of her life. Her life, from here on, was a profile in what's now called Acute Radiation Syndrome or ARS. First came the hair-loss, then the internal bleeding. The fatigue she experienced never really left.

39/61

By the time she was 20, Dō-oh was completely bald. Whatever clumps of fuzz tried sprouting every now and then, fell off quickly. Her injuries didn't heal for years.

But...

None of this was as bad as the stigma that followed. She was a hibakusha.

By the time she was 20, Dō-oh was completely bald. Whatever clumps of fuzz tried sprouting every now and then, fell off quickly. Her injuries didn't heal for years.

But...

None of this was as bad as the stigma that followed. She was a hibakusha.

40/61

Technically as a hibakusha, she was just someone who got hit by a bomb. But in reality, she was an outcast. An untouchable.

The Japanese, unaware of how ARS worked shied away from hibakushas, basically anyone who was in Hiroshima or Nagasaki on Aug 6 and 9, 1945.

Technically as a hibakusha, she was just someone who got hit by a bomb. But in reality, she was an outcast. An untouchable.

The Japanese, unaware of how ARS worked shied away from hibakushas, basically anyone who was in Hiroshima or Nagasaki on Aug 6 and 9, 1945.

41/61

ARS does affect the DNA but the fear was so intense, nobody would ever wanna marry, much less, make babies with, a hibakusha. Girls who until only yesterday fantasized handsome soldier grooms were now relegated to a life of solitude and destitution.

ARS does affect the DNA but the fear was so intense, nobody would ever wanna marry, much less, make babies with, a hibakusha. Girls who until only yesterday fantasized handsome soldier grooms were now relegated to a life of solitude and destitution.

42/61

The very year after the bombing, President Truman signed an order to create a team of experts. This team was to study the effects of radiation exposure in general and ARS in particular. It was called the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission or ABCC.

The very year after the bombing, President Truman signed an order to create a team of experts. This team was to study the effects of radiation exposure in general and ARS in particular. It was called the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission or ABCC.

43/61

One day in 1949, a non-Japanese car pulled over outside Dō-oh's home. A man emerged and knocked at her for.

He was from the ABCC and had come to take Dō-oh to the Shinkozen Elementary School for research. This was hope! Finally there could be a cure!

Dō-oh readily agreed.

One day in 1949, a non-Japanese car pulled over outside Dō-oh's home. A man emerged and knocked at her for.

He was from the ABCC and had come to take Dō-oh to the Shinkozen Elementary School for research. This was hope! Finally there could be a cure!

Dō-oh readily agreed.

44/61

Dō-oh was going to be part of a study that would determine not only how radiation affects humans but also how much of it is lethal. This study would establish metrics like acceptable radiation dose limits for medical practitioners, scientists, and other workers.

Dō-oh was going to be part of a study that would determine not only how radiation affects humans but also how much of it is lethal. This study would establish metrics like acceptable radiation dose limits for medical practitioners, scientists, and other workers.

45/61

Although the world had known radioactivity for at least half a century by then, this was the first time a real study of its effects was being done. Never before were so many test subjects available at once. The hibakusha was a labrat. For the greater good, of course.

Although the world had known radioactivity for at least half a century by then, this was the first time a real study of its effects was being done. Never before were so many test subjects available at once. The hibakusha was a labrat. For the greater good, of course.

46/61

Being a metaphorical labrat is one thing, but being actually treated like one? That isn't something Dō-oh had thought of in her excited optimism.

The hibakusha were to be studied, not treated. Because treating them would mean acknowledging moral responsibility. For what?

Being a metaphorical labrat is one thing, but being actually treated like one? That isn't something Dō-oh had thought of in her excited optimism.

The hibakusha were to be studied, not treated. Because treating them would mean acknowledging moral responsibility. For what?

47/61

For the nuclear bombing, something America wasn't willing to or comfortable doing. On paper the ABCC was a joint US-Japanese project but in reality, the clout was heavily on the American side. Also, the two groups didn't trust each other much, so there was that too.

For the nuclear bombing, something America wasn't willing to or comfortable doing. On paper the ABCC was a joint US-Japanese project but in reality, the clout was heavily on the American side. Also, the two groups didn't trust each other much, so there was that too.

48/61

For instance, only Americans were ever made directors. All research data was kept under American control. There was also this inexplicable wave gap between American and Japanese researchers. And Japanese doctors were never kept in the loop on new findings.

For instance, only Americans were ever made directors. All research data was kept under American control. There was also this inexplicable wave gap between American and Japanese researchers. And Japanese doctors were never kept in the loop on new findings.

49/61

Shinkozen Elementary was near the wet market at the wharf and had been converted into a makeshift hospital and research facility. This was also the ABCC's first Nagasaki office.

The first thing Dō-oh received once there was a white gown.

Shinkozen Elementary was near the wet market at the wharf and had been converted into a makeshift hospital and research facility. This was also the ABCC's first Nagasaki office.

The first thing Dō-oh received once there was a white gown.

50/61

She expected some treatment too. Pain relief if not anything else. But all she received there were cold indifferent stares from men studying her naked body and clicking pictures of her wounds. It was humiliating alright, but also physically traumatizing, she said.

She expected some treatment too. Pain relief if not anything else. But all she received there were cold indifferent stares from men studying her naked body and clicking pictures of her wounds. It was humiliating alright, but also physically traumatizing, she said.

51/61

Needless to say, there was zero emotional support. Refusal of medical treatment, as stated earlier, was not an administrative lapse. It was an active political mandate. America did not want to be seen as "atoning" for the bombing by treating the hibakusha.

Needless to say, there was zero emotional support. Refusal of medical treatment, as stated earlier, was not an administrative lapse. It was an active political mandate. America did not want to be seen as "atoning" for the bombing by treating the hibakusha.

52/61

Oh and the ABCC insisted that all studies be conducted during daytime. This meant loss of pay for the survivors who worked to make a living. Double whammy.

There was no government assistance either because until the late 1950s the govt. didn't even acknowledge them.

Oh and the ABCC insisted that all studies be conducted during daytime. This meant loss of pay for the survivors who worked to make a living. Double whammy.

There was no government assistance either because until the late 1950s the govt. didn't even acknowledge them.

53/61

Dō-oh never went back after that first visit. But thousands others did. And endured.

In hope.

The saga of humiliation and pain continued for years. Many hibakusha died without ever seeing light at the end of the ABCC tunnel. Many wished they did.

Dō-oh never went back after that first visit. But thousands others did. And endured.

In hope.

The saga of humiliation and pain continued for years. Many hibakusha died without ever seeing light at the end of the ABCC tunnel. Many wished they did.

54/61

By 1974, the Japanese had managed to get a much firmer handle on ABCC and a much improved clout at the UN. That's when things started to turn. That's when, almost 3 decades after the bombing, the ABCC was renamed the Radiation Effects Research Foundation or RERF.

By 1974, the Japanese had managed to get a much firmer handle on ABCC and a much improved clout at the UN. That's when things started to turn. That's when, almost 3 decades after the bombing, the ABCC was renamed the Radiation Effects Research Foundation or RERF.

55/61

The RERF had offices in Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki. Although a relief law had been in place in Japan since as early as 1957, it wasn't enough to help the hibakusha out of their squalor. Employers openly discriminated against the survivors, making jobs harder for them.

The RERF had offices in Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki. Although a relief law had been in place in Japan since as early as 1957, it wasn't enough to help the hibakusha out of their squalor. Employers openly discriminated against the survivors, making jobs harder for them.

56/61

That changed in 1975 when an amendment in the law made the hibakusha eligible for a health-protection allowance of 6,000 yens a month. Within years, this would gradually be doubled to accommodate inflation. Sure this has eased some of the pain with better treatment.

That changed in 1975 when an amendment in the law made the hibakusha eligible for a health-protection allowance of 6,000 yens a month. Within years, this would gradually be doubled to accommodate inflation. Sure this has eased some of the pain with better treatment.

57/61

Studies conducted by the ABCC continue to inform scientists and medical professionals today. They proved crucial in the handling of the 1986 Chernobyl meltdown and the 2011 Fukushima disaster.

What Dō-oh was part of is the world's only such study ever.

Studies conducted by the ABCC continue to inform scientists and medical professionals today. They proved crucial in the handling of the 1986 Chernobyl meltdown and the 2011 Fukushima disaster.

What Dō-oh was part of is the world's only such study ever.

58/61

What ABCC (and later, RERF) has done in the single largest study of its kind is beyond vital to the story of mankind.

What we often forget is...the price.

An estimated 190k hibakusha are still alive today. The youngest, exposed in utero, turned 75 this year.

What ABCC (and later, RERF) has done in the single largest study of its kind is beyond vital to the story of mankind.

What we often forget is...the price.

An estimated 190k hibakusha are still alive today. The youngest, exposed in utero, turned 75 this year.

59/61

While we enjoy the awe and wow of the big mushroom and the superlatives in its aftermath, it's important to know, understand, and acknowledge the role of the survivors left behind.

It's important to accept...

While we enjoy the awe and wow of the big mushroom and the superlatives in its aftermath, it's important to know, understand, and acknowledge the role of the survivors left behind.

It's important to accept...

60/61

That a fifth of a million innocent kids had to go through unspeakable horrors for the remainder of their lives for our doctors to know exactly how much is too much when doing an MRI or rating a cell phone.

That the tragedy didn't end with the bombs, it started with them.

That a fifth of a million innocent kids had to go through unspeakable horrors for the remainder of their lives for our doctors to know exactly how much is too much when doing an MRI or rating a cell phone.

That the tragedy didn't end with the bombs, it started with them.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter