The 1st paper from my thesis is up on @biorXivpreprint!

Main question: how do skin cells know when (and where) injury has occurred nearby?

A about how #zebrafish embryos sense wounds via osmotic AND electric cues, with plenty of cool movies! (1/12)

about how #zebrafish embryos sense wounds via osmotic AND electric cues, with plenty of cool movies! (1/12)

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.05.237792v1

Main question: how do skin cells know when (and where) injury has occurred nearby?

A

about how #zebrafish embryos sense wounds via osmotic AND electric cues, with plenty of cool movies! (1/12)

about how #zebrafish embryos sense wounds via osmotic AND electric cues, with plenty of cool movies! (1/12)https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.05.237792v1

skin cells respond to wounds FAST: within seconds after injury, cells 100s of microns away start reacting. How do they know so quickly?

skin cells respond to wounds FAST: within seconds after injury, cells 100s of microns away start reacting. How do they know so quickly?(Most movies in this

are of LifeAct-GFP in the basal cell layer of the embryonic tailfin, reacting to a wound to the right.) (2/12)

are of LifeAct-GFP in the basal cell layer of the embryonic tailfin, reacting to a wound to the right.) (2/12)

One way (that was previously known): because

are freshwater fish, injury = hypotonic shock. After wounding, dilute outside fluid mixes with salty inside fluid, cells swell up, and thereby detect the wound. See this side view of cells expressing plasma membrane GFP. (3/12)

are freshwater fish, injury = hypotonic shock. After wounding, dilute outside fluid mixes with salty inside fluid, cells swell up, and thereby detect the wound. See this side view of cells expressing plasma membrane GFP. (3/12)

are freshwater fish, injury = hypotonic shock. After wounding, dilute outside fluid mixes with salty inside fluid, cells swell up, and thereby detect the wound. See this side view of cells expressing plasma membrane GFP. (3/12)

are freshwater fish, injury = hypotonic shock. After wounding, dilute outside fluid mixes with salty inside fluid, cells swell up, and thereby detect the wound. See this side view of cells expressing plasma membrane GFP. (3/12)

Remarkably, previous work showed that if you put embryos in an isotonic solution (like PBS), cells don’t respond to the wound, esp. cells further away.

I was initially studying what caused cells to STOP moving after injury, and I used this trick to control their response. (4/12)

I was initially studying what caused cells to STOP moving after injury, and I used this trick to control their response. (4/12)

BUT -- I noticed not all isotonic solutions were equally effective: NaCl worked better than other solutions!

E.g. in isotonic CholineCl or NaGluconate, cells still reorganized their actin cytoskeletons, while practically nothing happened in isotonic NaCl. (5/12)

E.g. in isotonic CholineCl or NaGluconate, cells still reorganized their actin cytoskeletons, while practically nothing happened in isotonic NaCl. (5/12)

This is inconsistent with the idea of an osmotic wound cue, which should work equally well regardless of osmolyte. I tried a LOT of osmolytes, and found that isotonic NaCl inhibited a wound response more than any other osmolyte.

What’s going on? (6/12)

What’s going on? (6/12)

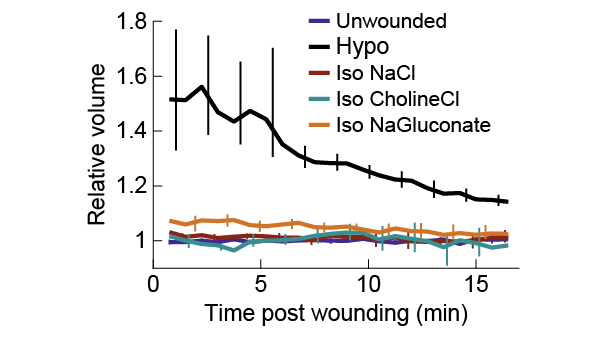

Maybe other osmolytes cause cells to swell for some non-osmotic reason, preserving some of the wound response? I directly measured cell volume, and found that’s not the case: all osmolytes prevent cell swelling to very similar extents.

So why is NaCl special? (7/12)

So why is NaCl special? (7/12)

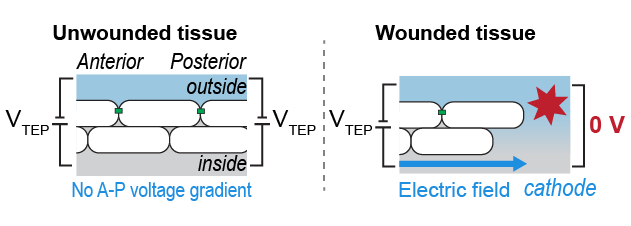

Here cell biology meets fish physiology: fish work hard to actively transport Na+ and Cl- ions across their skin, which generates a transepithelial electrical potential (TEP, different from transmembrane potential). At a wound the TEP is short-circuited, leading to… (8/12)

...Electric fields! Lateral TEP gradients between the wound and distant areas generate E-fields directed towards the wound.

The role of these E-fields in slow processes like regeneration has been well-studied. Could they also help guide cells immediately after wounding? (9/12)

The role of these E-fields in slow processes like regeneration has been well-studied. Could they also help guide cells immediately after wounding? (9/12)

To test this I directly applied electric fields to the skin cells in intact embryos, and I could initiate and reverse cell movement with electric fields--in the absence of a wound. Reminiscent of the SCHEEPDOG electric control device from @DJCohenEtAl, but in vivo! (10/12)

Moreover, when I wounded the embryo AND applied an E-field in the opposing direction I could override normal wound cues, so that cells followed the E-field!

In summary, E-fields could act in concert with osmotic cues to initiate and guide rapid wound responses in vivo (11/12)

In summary, E-fields could act in concert with osmotic cues to initiate and guide rapid wound responses in vivo (11/12)

There’s still a lot to learn about the interplay of osmotic and electric cues, the physiology behind these E-fields, and the mechanisms by which cells respond to E-fields.

I hope this work encourages others to use #zebrafish as an in-vivo system for further discovery! (end/12)

I hope this work encourages others to use #zebrafish as an in-vivo system for further discovery! (end/12)

THANK YOU to Julie and other Theriot lab members (esp. @SatheMugdha, Ellie Labuz, and Chris Prinz), @RaibleLab, @jraslab, Darren Gilmour, Alvaro Sagasti, Philippe Mourrain, and many, many others for help throughout the years, feedback on the manuscript, and great inspiration!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter