I’ve got a small number of followers here, and only a small percentage of those are in Ireland, so this thread to follow needs a little context.

It might appeal to people interested in sports, leadership, belief, spirituality, mysticism and extreme good fortune. Here goes.

It might appeal to people interested in sports, leadership, belief, spirituality, mysticism and extreme good fortune. Here goes.

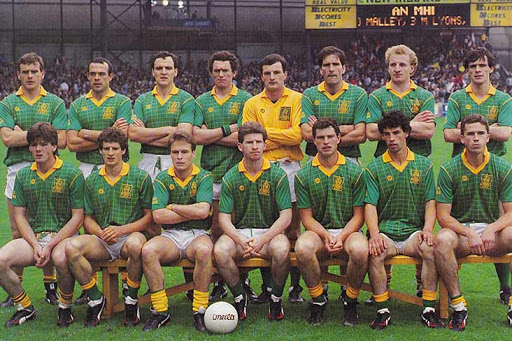

Tonight, on RTE television in Ireland, a documentary goes out. It’s called, simply, “Seán”, and it’s going to tell some of the story of the legendary Meath Gaelic football coach, Seán Boylan.

https://www.rte.ie/sport/gaa/2020/0730/1156467-Seán-meaths-managerial-marvel/

#SeanBoylan #Sean

https://www.rte.ie/sport/gaa/2020/0730/1156467-Seán-meaths-managerial-marvel/

#SeanBoylan #Sean

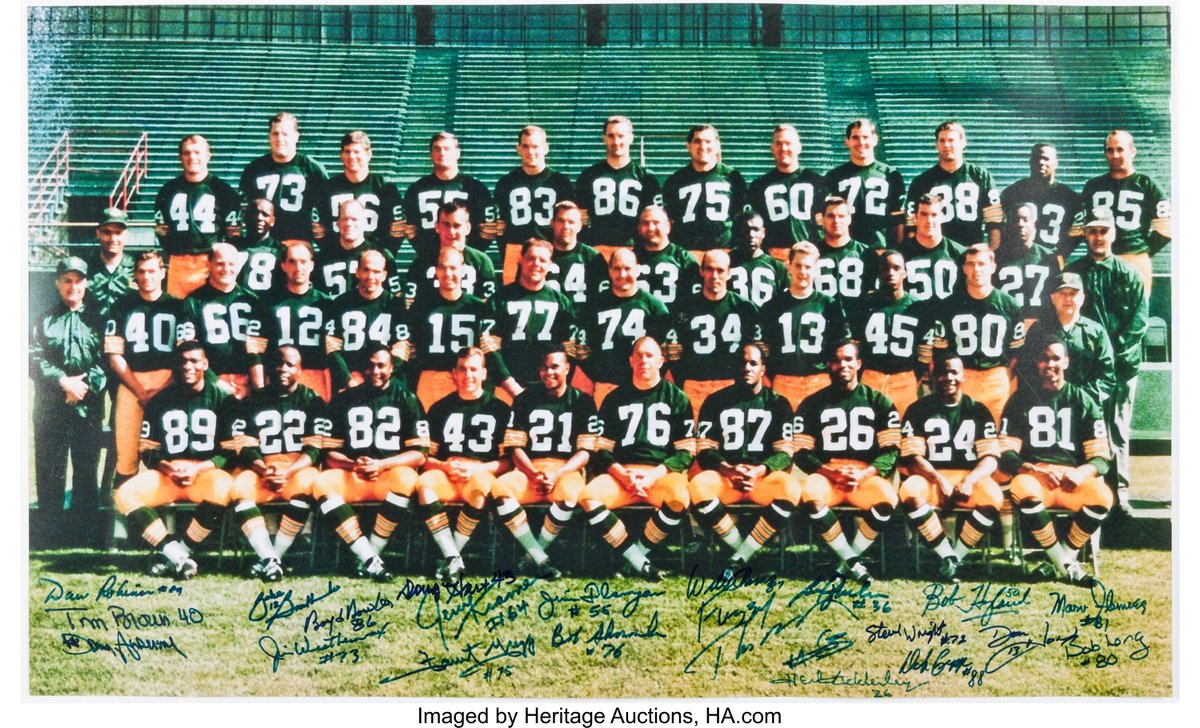

If you’ve no idea about Gaelic football but you're into US sports, Vince Lombardi is a decent comparison, and not just because the Meath Gaelic football team and the Green Bay Packers both play in beautiful green and gold.

From a young age, Boylan wanted to be a Cistercian monk, but eventually decided against the monastic life.

He said, “I went in and the monks were there, at prayer. Suddenly, something just hit me. I need God I thought, but I need God and the world.” (GAA interview, A. Sullivan)

He said, “I went in and the monks were there, at prayer. Suddenly, something just hit me. I need God I thought, but I need God and the world.” (GAA interview, A. Sullivan)

At 12, Lombardi was an altar boy on Easter Sunday.

"Amid the color and pageantry, scarlet and white vestments, golden cross, scepters, the wafers and wine, body and blood ... the inspiration came to him that he should become a priest." ("When Pride Still Mattered", D. Maraniss)

"Amid the color and pageantry, scarlet and white vestments, golden cross, scepters, the wafers and wine, body and blood ... the inspiration came to him that he should become a priest." ("When Pride Still Mattered", D. Maraniss)

Boylan became Meath manager in 1982. Meath had won All-Ireland Championships in 1949, ‘54 and ‘67, so had plenty of heritage, but there were many lean years before he came. The Packers had won six NFL titles but when Lombardi took the job in 1959, they'd had 15 wilderness years.

There's a physical resemblance between them too. The Internet says Vince Lombardi was five-foot-eight.

It doesn't say what height Seán is but he's certainly no more, and probably an inch or two shorter. These two men were giants in a world of men who towered above them.

It doesn't say what height Seán is but he's certainly no more, and probably an inch or two shorter. These two men were giants in a world of men who towered above them.

Memory is fragile, untrustworthy, but I have a memory of being at Croke Park in May 1984 as Meath played Monaghan in the final of the Centenary Cup. It was a special one-off competition to celebrate 100 years of the GAA. Meath won. That was the start of it. I was six years old.

Two years later, our summer holiday was a little cottage on Achill, an island jutting into the Atlantic Ocean on Ireland's west coast. While we were there, Meath played Dublin in the Leinster final (provincial championship).

Dublin had been top dogs. Their annual rivalry was with Kerry, maybe the greatest team ever to play the game. I doubt the game was live on TV, so it must have been that night that I watched highlights in the lounge of a pub in Achill.

The rain poured down, and even to my eight-year-old self watching on a little TV in a pub 150 miles away, I could recognise a war of attrition when I saw it. Meath won, 0-9 to 0-7. (For context, the winning total 0-9 — nine points — would not be a great first half score.)

Few weeks later, I was definitely at Croke Park for an All-Ireland semi-final against Kerry. My father lifted me over the turnstiles and I stood between his legs and watched the game. Meath put up a fight (more on this soon), but Kerry were too good / too clever and won by seven.

That game in August 1986 was the start of a heady period for Meath people. I have an eight-year-old boy now, and if he experiences anything close to what I experienced over the next few years, he has extraordinary bliss ahead.

1987 was the breakthrough. Kerry (in Munster) and Dublin (in Leinster) were fading, and Cork and Meath were rising. They met in the All-Ireland final of 1987, and Meath won, a first All-Ireland in 20 years. (All-Ireland tickets are hard to come by, so I watched that in a pub.)

Around then, the Meath team started to have training sessions at Dalgan Park, a seminary for missionary priests, and for some reason (no doubt influenced by Seán’s faith) had post-training meals at Bellinter House, then a convent run by the nuns of Our Lady of Sion.

Get this for good luck. A man who would become one of the greatest managers in history took over my county when I was five, made them All-Ireland champions, then selected locations for training and meals that would take the team past my front door TWO EVENINGS EVERY WEEK!

I see our kids and kids everywhere now. Their heroes are often on YouTube and speak with American accents. My heroes drove past several times a week, and I sat on the wall, waving a green and gold flag and wearing a jumper which my mam knitted to be EXACTLY like the Meath jersey.

A short aside. Depression runs in my family. A certain type of personality (shy, introspective, sensitive) makes some people more susceptible, I think. I know this for sure: Through my childhood and into adulthood, I struggled to believe many straightforward things were possible.

When I watched the Meath team, though, crafted and created by Seán Boylan and his team, my belief was rock-solid. Meath gained a reputation: We were never beaten. Five points down? We’ll come back. Eight points down? We’ll come back. Ten points down? Keep the faith

It was ridiculous to witness. Time after time, some opposing team would start brilliantly and go four, five, six points ahead. But even then, their players and supporters fully expected a Meath comeback. And when that started, the energy would drain visibly from all of them.

Summers passed. Seán's Meath showed up at Croker for big games every year. Eight-year-old me watched from between my dad's legs, but independent 13-year-old me stood on the Canal End among thousands of Meath supporters. Each one of us had a level of belief that bordered on crazy.

Meath played Dublin in four crazy games in 1991. All draws meant replays. They drew three times in a month. By Game 4, the whole country was watching. With a minute to go, Meath were four points behind. A free brought it back to three. We needed a goal.

I remember when the ball hit the net, Kevin Foley, who never, ever scored, arrived on the end of a sweeping move. Sheer joy and jubilation 200 yards away on the Canal End. We scarcely got our breath when David Beggy scored the point to win it.

On the TV highlights later, we heard Ger Canning, the commentator, say, “We were writing the Meath obituary. We obviously hadn’t the faith that the players had ... We should have known, because we’ve seen them ever since 1986. You can’t keep a good Meath team down.”

I was 13, and I had seen alcohol up close but had yet to taste it, my parents were still sort of together, I had seen no pornography, had yet to lose hundreds on a horse, and Meath were playing at Croke Park and the sun was shining and the world was pure bliss.

More All-Irelands came ('96 and '99), but more than that, Meath became hated. Boylan was always a gentleman, dignified in victory, gracious in defeat. But there had to be a steely craziness to him too. It came out in his teams. Whatever it took, it got. The games were ferocious.

I was 27 when Seán managed Meath for the last time. As these things often go, the last year or two had seen a decline, and after more than 20 years in the job and four All-Irelands, maybe he had done everything he could have done.

I met Seán last year, and had a brief chat. He wore a cream suit. It was like meeting God.

As part of my own self and mindset work, I have an imaginary board of advisers. I close my eyes and seek their counsel. In my mind, Seán Boylan and Tom Brady get on like a house on fire.

As part of my own self and mindset work, I have an imaginary board of advisers. I close my eyes and seek their counsel. In my mind, Seán Boylan and Tom Brady get on like a house on fire.

Seán was a miracle worker as Meath manager. By day, he's a herbalist. Many consider him a healer. Many years ago, a friend of mine suffered life-changing injuries in an accident.

Some time back he sat in a room with Seán.

Seán closed his eyes.

Five minutes passed. My friend wondered if he was asleep. Then Seán opened his eyes and gave firm instructions for a simple exercise.

Seán closed his eyes.

Five minutes passed. My friend wondered if he was asleep. Then Seán opened his eyes and gave firm instructions for a simple exercise.

I met this friend recently.

"How’s it going with the exercise Boylan gave you?" I asked.

So far, so good, he says. Balance is a problem, but he’s walking further now than he’s walked in years.

"How’s it going with the exercise Boylan gave you?" I asked.

So far, so good, he says. Balance is a problem, but he’s walking further now than he’s walked in years.

He believes.

That’s the thing about Seán. He makes us believe things our rational minds say we should not consider. Whether it’s because of that belief, or the things we do because we believe, or something else that lies beneath the surface of what we see, Seán gives that to us

That’s the thing about Seán. He makes us believe things our rational minds say we should not consider. Whether it’s because of that belief, or the things we do because we believe, or something else that lies beneath the surface of what we see, Seán gives that to us

I'll be watching "Seán" tonight.

I'm 42 now, and Meath are more than 20 years without an All-Ireland again.

No-one but Seán has managed Meath to one in more than 50 years.

I'm 42 now, and Meath are more than 20 years without an All-Ireland again.

No-one but Seán has managed Meath to one in more than 50 years.

As I watch, part of me will be standing between my father's legs at Croke Park. Another part of me will be on the old Canal End which no longer exists, with thousands of others who believed with every fibre of our being that no matter what the scoreboard said, we could still win.

And another part of me will be sitting on the garden wall, waving my flag as my heroes drive past on the country road outside the house where we grew up.

And I'll probably cry, because Seán made life worth the best kind of tears.

And I'll probably cry, because Seán made life worth the best kind of tears.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter