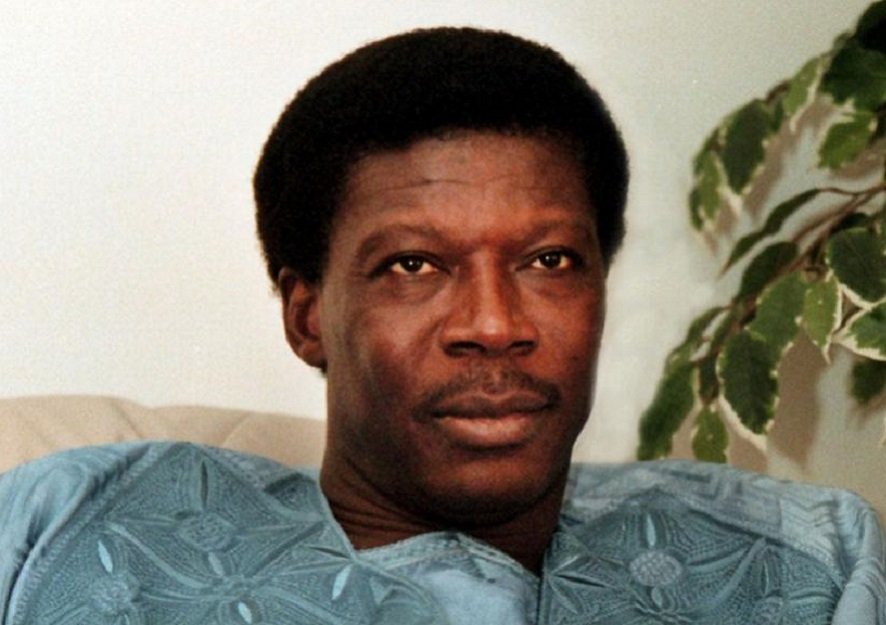

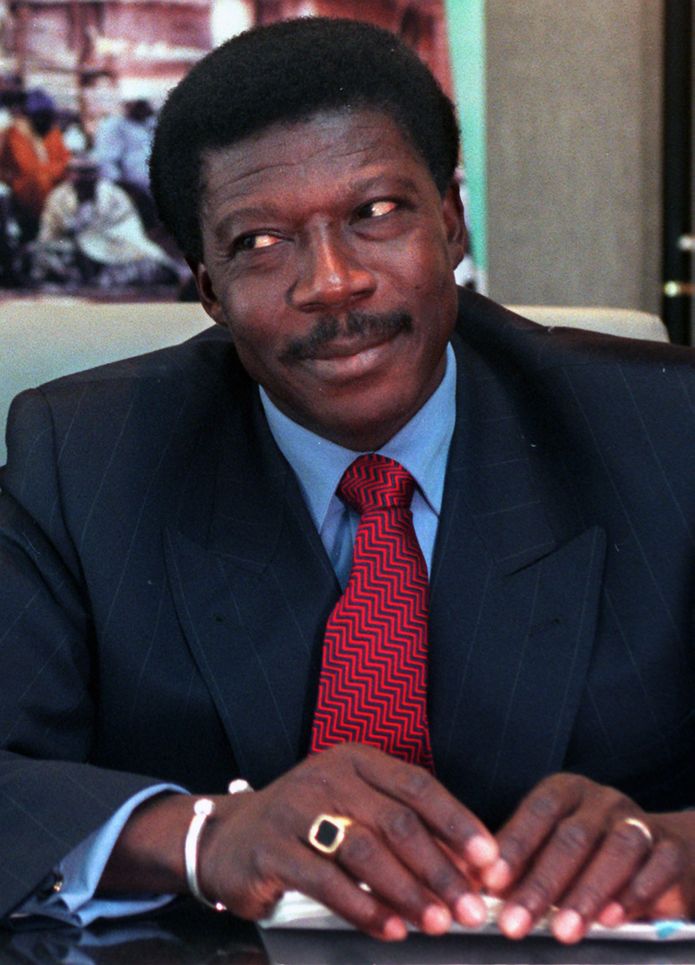

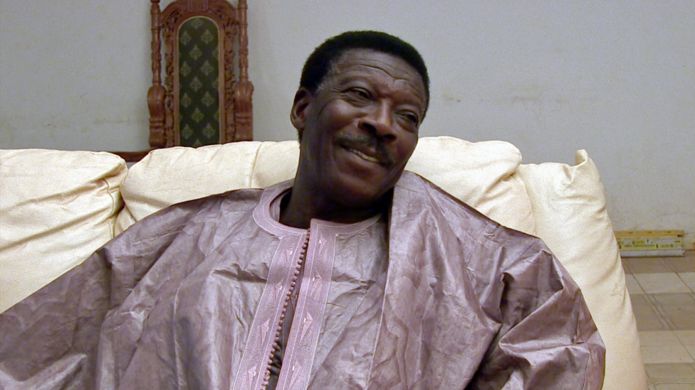

Foutanga Babani Sissoko born in the village of Dabia, not far from Mali’s capital, Bamako, little is known of Sissoko's early life, raised in a poor rural village in western Mali, Sissoko never attended school and is functionally illiterate.

A devout Muslim, he prays several times a day in his native language, Bambara. He speaks no English and poor French, Nonetheless, Sissoko is “incredibly charismatic, like a movie star. He is thin, about 6-foot-2, and he has the ability to take over a room

even without speaking the language.

One day in August 1995 Foutanga Babani Sissoko walked into the head office of the Dubai Islamic Bank and asked for a loan to buy a car. The bank manager at the time, Mohammed Ayoub, manager and Sissoko invited him home for dinner.

One day in August 1995 Foutanga Babani Sissoko walked into the head office of the Dubai Islamic Bank and asked for a loan to buy a car. The bank manager at the time, Mohammed Ayoub, manager and Sissoko invited him home for dinner.

It was the prelude, writes the BBC’s Brigitte Scheffer, to one of the most audacious confidence tricks of all time. Over dinner, Sissoko made a startling claim. He told the bank manager, Mohammed Ayoub, that he had magic powers. With these powers, he could take a sum of money

and double it. He invited his Emirati friend to come again, and to bring some cash and he would show him his powers.

Most Westerners see black magic or voodoo as an African thing. But in the middle east, such practices are a lot more familiar.

Most Westerners see black magic or voodoo as an African thing. But in the middle east, such practices are a lot more familiar.

Islam is as much a religion as a way of life in these parts and it frowns on the belief in and practice of black magic as paganism. Yet, for Ayoub, the allure was too strong. On his return, after an encounter with a stranger who warned him of the presence of a spirit

- a djinn, Ayoub stepped into the magic room and put his money forward.

He said he saw lights and heard strange sounds-phenomena easily associated with the supernatural. By the time the hoopla died down, his money was indeed doubled. Ayoub was ecstatic.

He said he saw lights and heard strange sounds-phenomena easily associated with the supernatural. By the time the hoopla died down, his money was indeed doubled. Ayoub was ecstatic.

He had found a way to double the money. As manager of a bank with millions of dollars at his behest, he could make millions in profits.

“So he would send money to Mr Sissoko — the bank’s money — and he expected it to come back in double the amount.”

“So he would send money to Mr Sissoko — the bank’s money — and he expected it to come back in double the amount.”

Over the next 3 years, Ayoub sent money to over 180 of Sissoko’s accounts in different locations around the world.

In 1998, news began to filter that the bank was in a cashflow crisis. The bank denied it.

They called it “a little difficulty

In 1998, news began to filter that the bank was in a cashflow crisis. The bank denied it.

They called it “a little difficulty

that did not lead to any financial losses either in the bank’s investments or depositors’ accounts.

But this was not the case.

Dubai Islamic Bank would have gone into bankruptcy, but for the government who stepped in to save the bank.

But this was not the case.

Dubai Islamic Bank would have gone into bankruptcy, but for the government who stepped in to save the bank.

By this time, Sissoko was far away. One of the beauties of his scheme was that he did not need to be in Dubai to keep receiving the money.

He caused a stir in 1995 when he flew into New York for a whirlwind shopping spree, spending millions on jewelry and cars

He caused a stir in 1995 when he flew into New York for a whirlwind shopping spree, spending millions on jewelry and cars

and handing out $100 bills on the street. He flew three planeloads of wives, family and hangers-on to Atlantic City, N.J., for a night of gambling at a Donald Trump casino.

Ever the smooth talker, in 1995, he had set the other part of his elaborate scheme in motion.

“He walked into Citibank one day, no appointment, met a teller and he ended up marrying her,” says Alan Fine, a Miami attorney the bank later asked to investigate the crime.

“He walked into Citibank one day, no appointment, met a teller and he ended up marrying her,” says Alan Fine, a Miami attorney the bank later asked to investigate the crime.

“And there’s reason to believe she made his relationship with Citibank more comfortable, and he ended up opening an account there through which, from memory, I’m just going to say more than $100m was wire transferred into the United States.”

Sissoko paid his new wife more than half a million dollars for her help.

Court and bank records would later show that between 1995 and 1998, money from the Dubai Islamic Bank was transferred to the following U.S. institutions:

Court and bank records would later show that between 1995 and 1998, money from the Dubai Islamic Bank was transferred to the following U.S. institutions:

*Citibank in New York received $37.2 million, which was deposited into an account bearing Sissoko’s name.

*Barnett Bank in Miami received $26.5 million, which was deposited into an account under the name Abdou Karim Pouye,

*Barnett Bank in Miami received $26.5 million, which was deposited into an account under the name Abdou Karim Pouye,

who has been described by Sissoko’s attorneys as his chief financial officer overseeing daily operations of Sissoko’s businesses

*City National Bank in Miami received $10.7 million for an account in Pouye’s name.

*City National Bank in Miami received $10.7 million for an account in Pouye’s name.

*NationsBank in Miami received $2.4 million for an account in Pouye’s name.

*First Union Bank in Miami received $1.4 million for an account in Pouye’s name.

*Commercebank National Association in Miami received $400,000 for an account in Pouye’s name, among others.

*First Union Bank in Miami received $1.4 million for an account in Pouye’s name.

*Commercebank National Association in Miami received $400,000 for an account in Pouye’s name, among others.

With these monies, Sissoko was able to open his dream airline for West Africa – Air Dabia, named after his village in Mali.

Sissoko’s name popped up in Miami in August 1996, when two of his employees were arrested after Customs officials alleged they offered a bribe in lieu

Sissoko’s name popped up in Miami in August 1996, when two of his employees were arrested after Customs officials alleged they offered a bribe in lieu

of the required export license for the two used helicopters, for which they had paid $270,000. In monitored telephone calls between those employees and Sissoko, federal agents said they heard him authorize the bribe. A warrant for his arrest was issued,

and Sissoko was picked up later that month by Interpol in Geneva he was arrested in Geneva, Europe, on a U.S. warrant and charged with trying to smuggle two Vietnam-era military helicopters out of Miami to Africa and offering a $30,000 bribe to a U.S. Customs agent,

the New York Times reported.

In anticipation of Sissoko’s coming to Miami, his representatives arrived to prepare the way. They bought several automobiles. They paid $3 million for five condominium apartments on Biscayne Bayand leased 10 apartments on the 26th floor

In anticipation of Sissoko’s coming to Miami, his representatives arrived to prepare the way. They bought several automobiles. They paid $3 million for five condominium apartments on Biscayne Bayand leased 10 apartments on the 26th floor

of a high-rise across the street. Tom Spencer, a Miami lawyer who was asked to represent Sissoko, vividly remembers going to meet him in Geneva's Champ-Dollon prison.

"I talked with the prison warden, who asked me whether or not Sissoko was going to go to the United States,"

"I talked with the prison warden, who asked me whether or not Sissoko was going to go to the United States,"

Spencer says.

"I said, 'Well, you know, we'll see.' And he said, 'Well, please delay it as long as possible.' And I said, 'Well why?' And he said, 'Because he's flying in fantastic meals from Paris every night, for us.' And that was my first bizarre encounter with Baba Sissoko."

"I said, 'Well, you know, we'll see.' And he said, 'Well, please delay it as long as possible.' And I said, 'Well why?' And he said, 'Because he's flying in fantastic meals from Paris every night, for us.' And that was my first bizarre encounter with Baba Sissoko."

Sissoko was quickly extradited to the US, where he started to mobilise influential supporters.

The readiness of diplomats to vouch for Sissoko shocked the judge presiding over his bail hearing. And Tom Spencer was stunned when a former US senator, Birch Bayh,

The readiness of diplomats to vouch for Sissoko shocked the judge presiding over his bail hearing. And Tom Spencer was stunned when a former US senator, Birch Bayh,

announced he was joining Sissoko's defence team.

Sissoko’s Washington friends rallied to his aid in 1996 after he was accused of offering a bribe to a U.S. Customs Service official for help in exporting a pair of military helicopters. Former Sen. Birch Bayh (D-Ind.),

Sissoko’s Washington friends rallied to his aid in 1996 after he was accused of offering a bribe to a U.S. Customs Service official for help in exporting a pair of military helicopters. Former Sen. Birch Bayh (D-Ind.),

now practicing law in Washington, tried to intervene at the Justice Department and the CIA. West African ambassadors to the United Nations attested to Sissoko’s character, as did members of the Congressional Black Caucus. After U.S. Rep. Corrine Brown (D-Fla.) wrote letters

on Sissoko’s behalf to Atty. Gen. Janet Reno and Treasury Secretary Robert E. Rubin, Brown’s daughter received a $60,000 Lexus from Sissoko’s chief financial officer.

When Sissoko showed up in October 1996, he went straight to the federal courthouse, where he was arraigned

When Sissoko showed up in October 1996, he went straight to the federal courthouse, where he was arraigned

on charges of bribery and export violations. His bond was set at $20 million, the highest ever in the southern district of Florida. He paid it within hours. Right after, the man, who was described as a multimillionaire philanthropist, began blowing all of his money in Miami.

He bought about 35 expensive cars – including buying each of his three Miami lawyers a $65,000 Mercedes-Benz 300SL and some jaguar cars for his defense team – rented 23 apartments, married more wives, and gave away large amounts of money to charity –

over a million dollars a month.Sissoko spent half a million dollars in one jewellery store alone, Fine recalls, and hundreds of thousands in others. In one men’s clothing store he spent more than $150,000.

“He would come in and buy two three four cars at the same time, come back another week and buy cars the same time. It was just, the money was like wind,” says car dealer Ronil Dufrene.

He calculates that he sold Sissoko 30 to 35 cars in total. Baba became a Miami celebrity.

He calculates that he sold Sissoko 30 to 35 cars in total. Baba became a Miami celebrity.

"Playboy’ is the right word to describe him. Because he is very elegant. And handsome. And he dresses with great style. He blew a lot of money in Miami,” says Sissoko’s cousin, Makan Mousa.Sissoko was also giving away large sums to good causes. His trial was approaching,

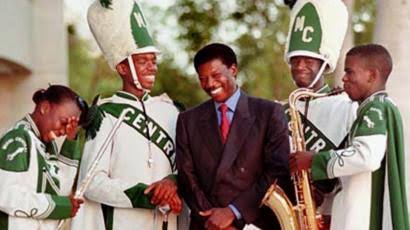

and he knew the value of good publicity. In one case witnessed by his cousin, he gave £300,000 to a high-school band that needed money to travel to New York for a Thanksgiving Day parade.

For the Miami Central High marching band, the money that appeared for new uniforms,

For the Miami Central High marching band, the money that appeared for new uniforms,

instruments and airline tickets to New York so that they could strut their stuff in last year’s Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade was nothing short of magic.

“We were blessed,” said band director Shelby Chipman after West African millionaire Foutanga Dit Babani Sissoko

“We were blessed,” said band director Shelby Chipman after West African millionaire Foutanga Dit Babani Sissoko

wrote out a check for $300,000 minutes after running into fund-raising band members playing dance tunes at a bar mitzvah in a downtown hotel.

Over the next few months, Sissoko used his vast wealth to buy legal and political clout. In Miami, Spencer and other lawyers worked on an entrapment defense, while Bayh and friendly lawmakers argued in Washington that Sissoko was a special envoy of Gambia

and thus enjoyed diplomatic immunity.

But Sissoko did not put all his faith in the American justice system. After tribal potions were brought in from West Africa, he ordered that a special powder be sprinkled around the courthouse.

But Sissoko did not put all his faith in the American justice system. After tribal potions were brought in from West Africa, he ordered that a special powder be sprinkled around the courthouse.

A violet-colored liquid was released into Biscayne Bay.

Another of his defence lawyers, Prof H T Smith, remembers that on Thursdays he would drive around giving money to homeless people.

I was thinking, is this some modern day Robin Hood?

Another of his defence lawyers, Prof H T Smith, remembers that on Thursdays he would drive around giving money to homeless people.

I was thinking, is this some modern day Robin Hood?

Why would you steal money and give it away? It doesn’t make any sense,”

“The [Miami] Herald did a story just after he left,–I don’t want to exaggerate but I think they said they could chronicle like $14m he gave away. He was here 10 months. That’s over a million dollars monthly.

“The [Miami] Herald did a story just after he left,–I don’t want to exaggerate but I think they said they could chronicle like $14m he gave away. He was here 10 months. That’s over a million dollars monthly.

Alan Fine took a slightly more cynical view.

“So much of what he did was for image and to perpetuate a belief that he was a very powerful man and fabulously wealthy. He would give away money, but… to my knowledge it was never done in a way that he didn’t get publicity for it.”

“So much of what he did was for image and to perpetuate a belief that he was a very powerful man and fabulously wealthy. He would give away money, but… to my knowledge it was never done in a way that he didn’t get publicity for it.”

Despite this PR drive, when Sissoko’s case came to court he disregarded his lawyers’ advice and pleaded guilty.

Maybe he calculated that this would provoke fewer questions about his finances.

Maybe he calculated that this would provoke fewer questions about his finances.

The sentence was 43 days in prison and a $250,000 fine – paid, of course, by the Dubai Islamic Bank, though without its knowledge. But his attorneys continued to press for a dismissal of the bribery charge. In a final courthouse hearing in June,

Sissoko supporters included the ambassadors of Gambia, Mali, Senegal and Togo; actor Sherman Helmsley, a star of “The Jeffersons” TV show; and several supporters of the South Florida Coalition to Free Babani Sissoko.

Even after Sissoko was sentenced to a minimum-security prison, his lawyers continued to argue that their client was a victim of cultural persecution. “In Sissoko’s culture, not only is [giving gifts to government officials] legal, it is expected of a rich African chief,”

wrote H. T. Smith in an opinion piece in the Miami Herald.

A British investigator hired by the bank says the transfers of funds to Sissoko-controlled accounts in Europe and at Citibank in New York began in 1995 and continued until March 1998.

A British investigator hired by the bank says the transfers of funds to Sissoko-controlled accounts in Europe and at Citibank in New York began in 1995 and continued until March 1998.

After serving only half this sentence, he was given early release in return for $1.2 million to a Miami homeless shelter. The rest he was meant to serve under house arrest in Mali.

Instead he returned home to a hero’s welcome. In November, after a judge freed Sissoko from house arrest following his release from prison in the bribery case, Spencer was one of several dozen Miamians invited to join Sissoko on the ride home in a chartered Boeing 747.

After the nonstop flight from Miami to Bamako, Spencer said, Sissoko got off the plane in the Malian capital to a tumultuous welcome. Thousands turned up at the airport carrying welcoming signs and tossing flowers, and tens of thousands more lined the roads as his entourage

made the 45-minute journey to his house in the hills.

Having built schools, hospitals and roads in Mali, Spencer said, Sissoko “is a god there.”With a penchant for blessing total strangers with cash and cars, Sissoko seemed like something of a beneficent deity to many Americans.

Having built schools, hospitals and roads in Mali, Spencer said, Sissoko “is a god there.”With a penchant for blessing total strangers with cash and cars, Sissoko seemed like something of a beneficent deity to many Americans.

It was around this time that the Dubai Islamic Bank’s auditors began to notice that something was wrong. Ayoub was getting nervous, and Sissoko had stopped answering his calls.

Finally he confessed to a colleague, who asked how much was missing.

Finally he confessed to a colleague, who asked how much was missing.

Too ashamed to say, Ayoub wrote it on a scrap of paper – 890 million dirhams, the equivalent of $242m (£175m). When reports of the missing cash touched off a $500-million run on the Dubai bank.

“There is no documentation, nor has any witness indicated any business relationship

“There is no documentation, nor has any witness indicated any business relationship

between Sissoko and [the bank] that could possibly explain the outgoing transfers,” Alan R. Ellison said in a court affidavit. At least two Dubai bank officials, including the spellbound Saleh, are in custody, Fine said. "[Saleh] was stunned that the money wasn’t coming back

Sissoko told him that he could make money come back and make it grow.”

In a civil complaint unsealed in Miami in 1998, Sissoko, 53, is accused of embezzling $240 million from a Middle Eastern bank after bamboozling a bank officer with tribal voodoo.

In a civil complaint unsealed in Miami in 1998, Sissoko, 53, is accused of embezzling $240 million from a Middle Eastern bank after bamboozling a bank officer with tribal voodoo.

The banker “fell under Sissoko’s control” and began illegally transferring money from the Dubai Islamic Bank to Sissoko’s account, the suit alleges, after a black glass ball was hung over the banker’s bed. Mohammed Ayyoub Mohammed Saleh “claims that Sissoko convinced him

that Sissoko could use the glass ball to see what Saleh was doing,” according to the bank’s complaint.

The Justice and Treasury departments are investigating, as are officials in the United Arab Emirates and Switzerland, said Alan S. Fine, a Miami lawyer representing the bank.

The Justice and Treasury departments are investigating, as are officials in the United Arab Emirates and Switzerland, said Alan S. Fine, a Miami lawyer representing the bank.

“This guy was a world-class con man,” Fine said. Among those shocked by that characterization are many in Miami and Washington who were wooed by the devoutly Muslim Sissoko’s spiritual nature, as well as by his charitable instincts--

he was once invited by Democrats to a White House fund-raiser.

Ayoub was found guilty of fraud and given three years in jail. It’s rumoured he was also forced to undergo an exorcism, to cure him of his belief in black magic. Sissoko, on the other hand, has never faced justice,

Ayoub was found guilty of fraud and given three years in jail. It’s rumoured he was also forced to undergo an exorcism, to cure him of his belief in black magic. Sissoko, on the other hand, has never faced justice,

he has lived in Mali since, as a free man. In his absence, a Dubai Court sentenced him to three years for money laundering, fraud and practising magic. Interpol issued an arrest warrant and he remains a wanted man but he will never serve a day of that time.

In transcripts found from other trials at which Sissoko failed to appear, including one in Paris. His lawyer claimed he was a scapegoat for Ayoub’s actions and the bank’s money had gone elsewhere, but the court didn’t swallow it and convicted him of money-laundering.

For 12 years, between 2002 and 2014, Sissoko was a member of parliament in Mali, which gave him immunity from prosecution. Since then, the fact that Mali has no extradition treaty with the US, the UAE or any other country has been his saving grace.

“I have really been blindsided by this,” said attorney Thomas R. Spencer. “This is nothing I could ever imagine or suspect.”

Sissoko’s remaining Miami assets, down to about $2 million, have been frozen. In Jacksonville,a federal grand jury is looking into the gift

Sissoko’s remaining Miami assets, down to about $2 million, have been frozen. In Jacksonville,a federal grand jury is looking into the gift

to Brown’s daughter of the Lexus, which has been sold, the proceeds donated to charity. The band will be permitted to keep the uniforms, and the homeless shelter may not have to give back the money. But the lawyers’ cars could be in jeopardy. “I think they are not going to be

comfortable driving around in something purchased with stolen money,” Fine said.

Admitting he does not know the details of the case against Sissoko, Spencer said he finds the allegations “bizarre and implausible.”

Admitting he does not know the details of the case against Sissoko, Spencer said he finds the allegations “bizarre and implausible.”

“Human nature and banking being what it is, it is hard to understand how a person here in the U.S. for 18 months could effectively embezzle anything, black magic and magic orbs notwithstanding,” he said.

Indeed, the tale of Sissoko’s free-spending romp through America seems even more improbable when his curriculum vitae is examined.

The source of Sissoko’s wealth isn’t clear. Among the rags-to-riches myths: His fortune was made trading textiles in India.

The source of Sissoko’s wealth isn’t clear. Among the rags-to-riches myths: His fortune was made trading textiles in India.

Or oil was found on land he owned in his native Mali. Sissoko once suggested he struck it rich as a laborer in the diamond mines of Liberia. Sissoko, who worked as a house servant in India in his youth, started his entrepreneurial journey as a textile trader in that country.

Spencer, who counts his five days with Sissoko in Mali as “one of the most incredible experiences I’ve ever had,” said that even if the money that bought his Mercedes was stolen, he paid taxes on the car and will probably keep it.

But he is struggling with the notion of Sissoko as a thief.

“I’ve seen a lot of crooks here in Miami,” said Spencer, in practice for 30 years. “Usually, they are self-indulgent. But this was a guy who got more pleasure out of giving than utilizing money himself. "I have been

“I’ve seen a lot of crooks here in Miami,” said Spencer, in practice for 30 years. “Usually, they are self-indulgent. But this was a guy who got more pleasure out of giving than utilizing money himself. "I have been

out with him when he’d see some homeless person. He’d tell the driver, ‘Stop the car,’ and then go hand out money, $100 bills. He did that in Washington too.

“I’d really like to know the facts, just for my own satisfaction. But I suspect that we’ll never know the real truth.”

“I’d really like to know the facts, just for my own satisfaction. But I suspect that we’ll never know the real truth.”

The Dubai Islamic Bank, nonetheless, is still pursuing him through the courts.

There seems little hope in that course.

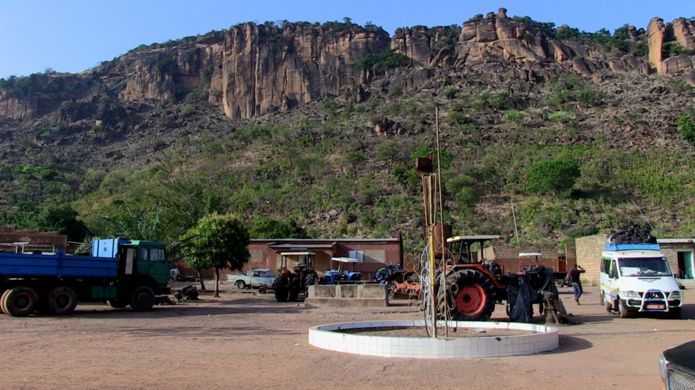

After a long intense search, Sissoko was found, now aged 70, in the town of Dabia where he was born.

There seems little hope in that course.

After a long intense search, Sissoko was found, now aged 70, in the town of Dabia where he was born.

He agreed to an interview. The atmosphere was edgy and slightly surreal. He began by talking about his entry into the world.

"My name is Sissoko Foutanga Dit Babani. You know, the day I was born all the villages round here burned down. The villagers went round shouting,

"My name is Sissoko Foutanga Dit Babani. You know, the day I was born all the villages round here burned down. The villagers went round shouting,

'Marietto has had a boy.' The fire leapt and leapt. There used to be a lot of bush around."

He then talked about his efforts to rebuild the village, which began in 1985, and about the money he made. At one point he had been worth $400m, he said.

He then talked about his efforts to rebuild the village, which began in 1985, and about the money he made. At one point he had been worth $400m, he said.

Eventually, he was asked about the $242m he had received from the Dubai Islamic Bank. He said "Madame, this $242m, this is a slightly crazy story. The gentlemen from the bank should explain how they lost all that money. I mean the $242m.

Listen, he said how could that money have left the bank the way it did? That's the problem. It's not this man alone [Ayoub] who authorises the transfers. When the bank transfers money it's not just one person who does it. Several people have to do it."

When pointed out to him that Mohammed Ayoub had claimed at his trial that Sissoko had put him under a spell.

"The gentleman you're talking about, I've seen him and met him," he said.

But the heist, he denied.

"The gentleman you're talking about, I've seen him and met him," he said.

But the heist, he denied.

"The only contact I had with him was when I went to buy a car. The bank bought it for me and I repaid the loan. It was a Japanese car."

When asked if he had controlled people with magic he replied "Madame, if a person has that kind of power, why would he work?

When asked if he had controlled people with magic he replied "Madame, if a person has that kind of power, why would he work?

If you have that kind of power you can stay where you are and rob all the banks of the world. In the United States, France, Germany, everywhere. Even here in Africa. You could rob all the banks you want." When further questioned if he was still rich,

His answer was blunt

"No I'm not rich any longer. I'm poor."

Defying Interpol, Sissoko has spent a remarkable 20 years on the run, even if he has squandered all his money and can never leave Mali.

He has never spent a day in jail for the black magic bank heist.

"No I'm not rich any longer. I'm poor."

Defying Interpol, Sissoko has spent a remarkable 20 years on the run, even if he has squandered all his money and can never leave Mali.

He has never spent a day in jail for the black magic bank heist.

Sources; BBC LA times Miami new times, Google, Wikipedia

Please like and retweet

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter