1/Yesterday Sean ( @shahanSean) briefly mentioned the doctrine of muḥādatha (محادثة). Typically the medieval literature describes non-prophetic person who converses with angels as muḥaddath (محدث). The prominent caliph ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb (d. 644) is identified as such person

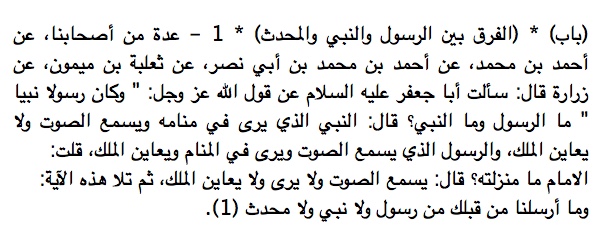

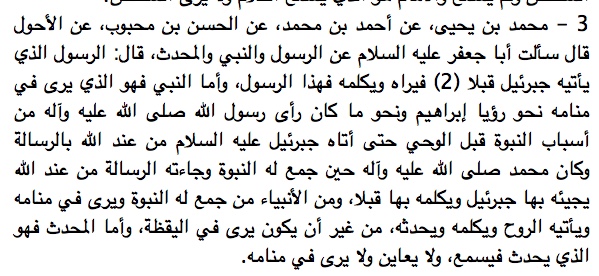

2/ It is well known in the early Islamic literature that the Shiʿis believed the Imams where conversant with God. In numerous reports recorded in al-Kāfī (Shiʿi ḥadīth canon) the Imām is said to be capable of audition. He is spoken to by the Angel yet he cannot see him.

3/Historians are quite suspicious the ḥadīth reports - and for good reason. Reports are tendentious and should not be seen as accounts of historical events but as vistas revealing the Weltanschauung of the competing factions of early Islam.

4/It has been argued by two prominent academic scholars of Islam that some early groups held on to the believe that ʿUmar was a prophet, or prophet-like, or someone with whom the angels conversed.

5/The first is Joseph van Ess (arguably the most outstanding contemporary intellectual historian of early Islam). Van Ess brings out attention to a fifteenth century Ibādī ʿaqīda (creed) written by Abū Ḥafs ʿUmar b. Jumayʿ, penned originally in Berber for North African Ibāḍīs

6/The creed appears to have been popular and significant, it received several Arabic commentaries, the most widely circulated being that of al-Shammākhī and al-Tallātī, both of whom died in sixteenth century AD.

7/The author, Jumayʿ, dismisses those who believe Abū Bakr and ʿUmar are prophets as beyond the pale of Ibāḍī belief. Van Ess notes that the commentators, Shammākhī and Tallātī, struggle to make sense of mere mention of this creedal pronouncement.

8/But for Van Ess the idea that Abū Bakr and more significantly ʿUmar were prophets is much older then the 15th C. Van Ess points to a tenth century (fourth hijri c) account in al-Muqaddasī who came across the idea in Isfahan (which includes ʿAlī and Muʿāwiya to the list)

9/Avraham Hakim agrees with Van Ess. He argues in many of his writings that the idea or theological belief in the prophecy of ʿUmar dates back to the early days of Islam.

10/Hakim refers to early reports that show ʿUmar was "granted the sublime ability to read God's mind." He adds that a number of "statements imply that several Qurʾānic rulings ... were fashioned on the basis of ʿUmar's views, ideas, or utterances." https://www.academia.edu/26369558/Context_Umar_b._al-Khattāb

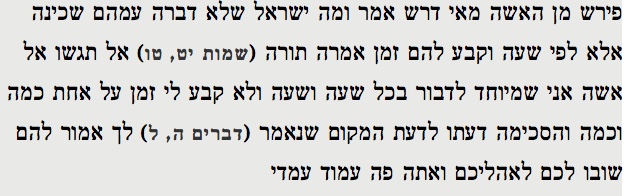

11/Hakim describes this early phenomena as "mutual agreement" between ʿUmar and the quranic revelation. Relying on an report attributed to ʿUmar himself, the second caliph is reputed to have said, "I agreed (wāfaqtū) with God on three matters" [Musnad Aḥmad]

12/In another version quoted in the canonical ḥadīth collections of Bukhārī and Muslim ʿUmar is quoted to have said, "God agreed with me."

13/The theological implication of these early reports is God agrees a posteriori to the matters that ʿUmar determined to be sound and probative. Muslim exegetes came to speak of these verses as muwāfaqāt ʿUmar, i.e. instances where ʿUmar agreed with God, & God agreed with ʿUmar

14/Hakim is of the opinion that the concept of ʿUmar's mutual agreements could have drawn influence from Judaism. For instance, in the Babylonian Talmud in Yevamot 62b, "Three things did Moses upon his own authority, and his view agreed with that of God."

15/Furthermore, early traditions in praise of ʿUmar seem to follow the image of Moses in fashioning the image of ʿUmar as the ideal leader. Hakim points to reports where the descriptions of ʿUmar are paralleled with Moses.

16/The specific examples recalled by Hakim are quite many, so we'll name a couple by way of example. First, in Quran 33.53 the verse of veiling (ḥijāb) commands believers regarding the wives of the Prophet & prohibits the wives from appearing unveiled infront of male strangers

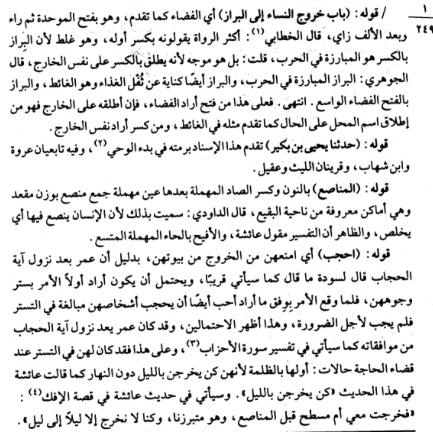

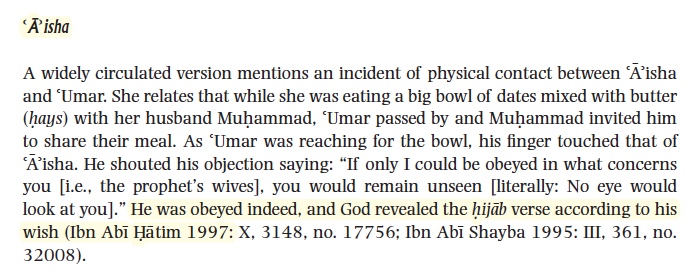

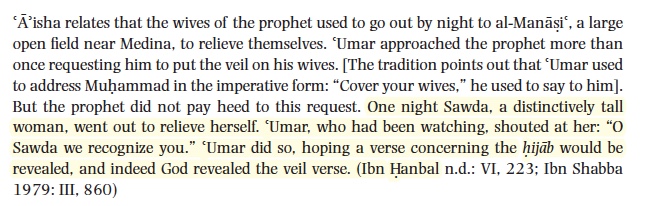

17/According to numerous reports and exegetes the verse was revealed after the intervention of ʿUmar who "did not look favourably on the fact that the wives of the prophet used to appear in public unveiled."

18/Hakim focuses on three different versions with three different wives of Muḥammad. First: ʿĀʾisha, recounted in Ibn Abī Ḥātim. Second, Sawda, recounted in Aḥmad's Musnad. And similarly with Zaynab.

19/Based on the representative early reports above, Van Ess (and to a lesser extent Hakim) conclude that there must have been an faction in early Islam who thought of ʿUmar as a prophet, but later authorities watered down these views to the more acceptable role of muḥaddath.END

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![11/Hakim describes this early phenomena as "mutual agreement" between ʿUmar and the quranic revelation. Relying on an report attributed to ʿUmar himself, the second caliph is reputed to have said, "I agreed (wāfaqtū) with God on three matters" [Musnad Aḥmad] 11/Hakim describes this early phenomena as "mutual agreement" between ʿUmar and the quranic revelation. Relying on an report attributed to ʿUmar himself, the second caliph is reputed to have said, "I agreed (wāfaqtū) with God on three matters" [Musnad Aḥmad]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EeCxNBLXsAAc1J6.jpg)

![11/Hakim describes this early phenomena as "mutual agreement" between ʿUmar and the quranic revelation. Relying on an report attributed to ʿUmar himself, the second caliph is reputed to have said, "I agreed (wāfaqtū) with God on three matters" [Musnad Aḥmad] 11/Hakim describes this early phenomena as "mutual agreement" between ʿUmar and the quranic revelation. Relying on an report attributed to ʿUmar himself, the second caliph is reputed to have said, "I agreed (wāfaqtū) with God on three matters" [Musnad Aḥmad]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EeCxYX3WAAESrLU.jpg)