1. Looking fwd to presenting a new article w/ @kristenkao Aug 3 @DukeCSJ workshop on the question: Do harsher punishments actually increase the public's willingness to support reintegration of former offenders as is often assumed (but not tested)? Thread... https://www.mararevkin.com/uploads/1/2/3/2/123214819/punishment_reintegration_revkin_kao_2020.7.28.pdf

2. on findings from a survey experiment in Iraq, where 19K+ are in prison for association w/ the Islamic State under a sweeping anti-terrorism law that criminalizes "membership" alone w/out requiring evidence of specific criminal acts—see @belkiswille @hrw https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/12/05/flawed-justice/accountability-isis-crimes-iraq

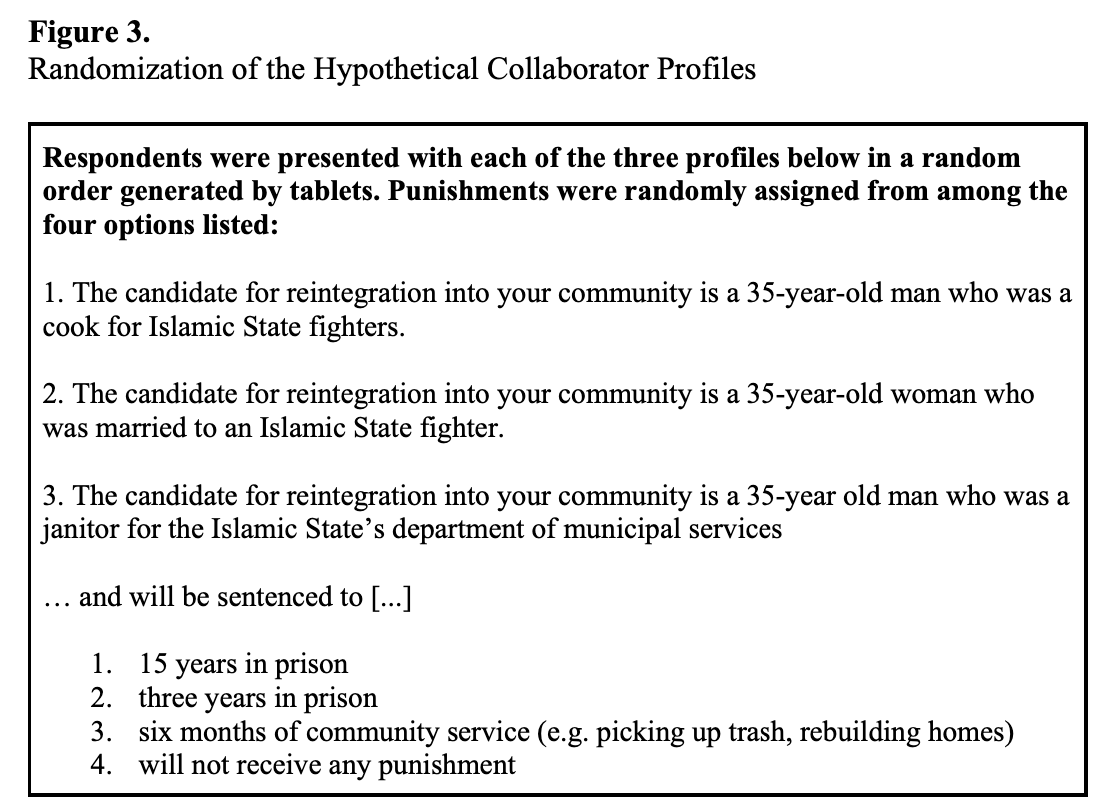

3. As a result, many nonviolent civilian "collaborators" (e.g. cooks, cleaners, wives of fighters) have been sentenced to long but less-than-life sentences raising the question: How will they be reintegrated into Iraqi society after their eventual release? https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2019/01/07/is-iraqs-post-islamic-state-justice-strategy-misguided/

4. Empirical research has challenged the effectiveness of incarceration for achieving its purported objectives including deterrence, incapacitation & retribution. We look at another outcome that has been less studied: public opinion toward reintegration of former offenders.

5. Studying public opinion toward former offenders in the communities to which they return is important because distrust, fear & stigmatization of former offenders makes it very difficult to rebuild social relationships & find employment, increasing their risk of recidivism.

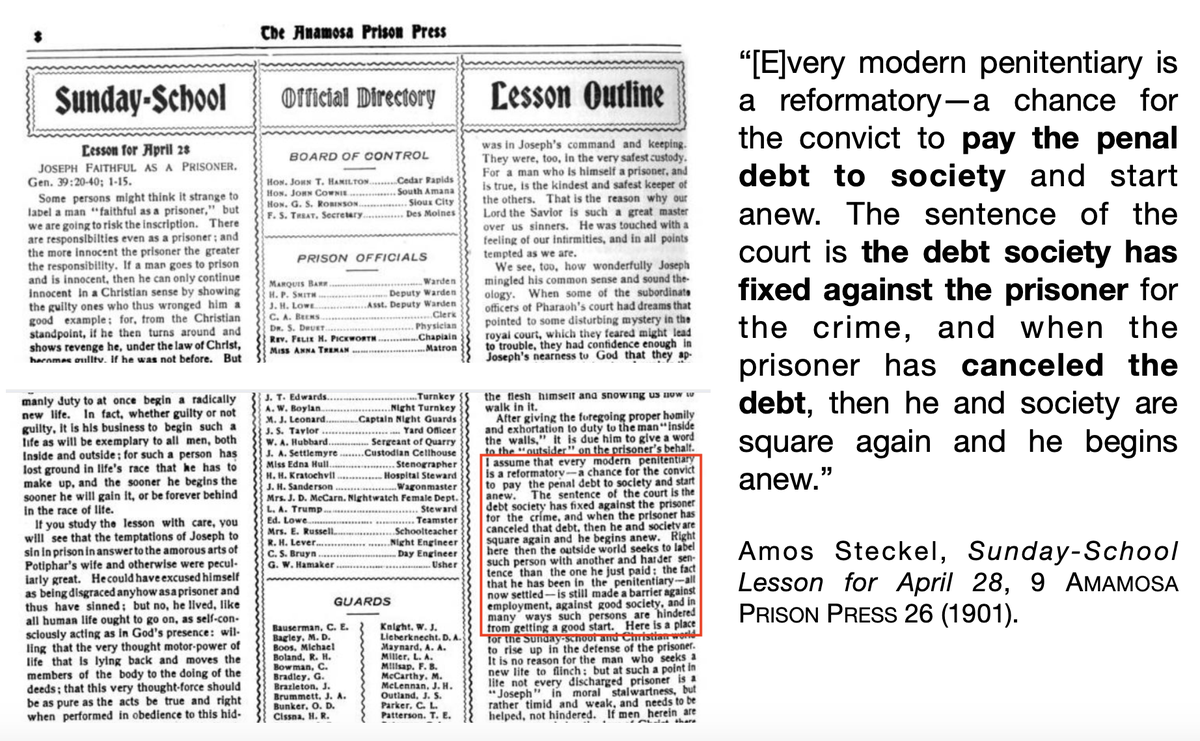

6. Historically, proponents of incarceration have argued that prison is necessary to convince the public that offenders have been fully rehabilitated & paid their "debt to society" as shown in this 1901 article from the Iowa State Penitentiary's newspaper:

7. This argument relies on empirical assumptions about what "society" wants. But, we don't actually know very much about public opinion re: necessary conditions for reintegration of former offenders in communities to which they return. In 2018 after the defeat of IS in Iraq ...

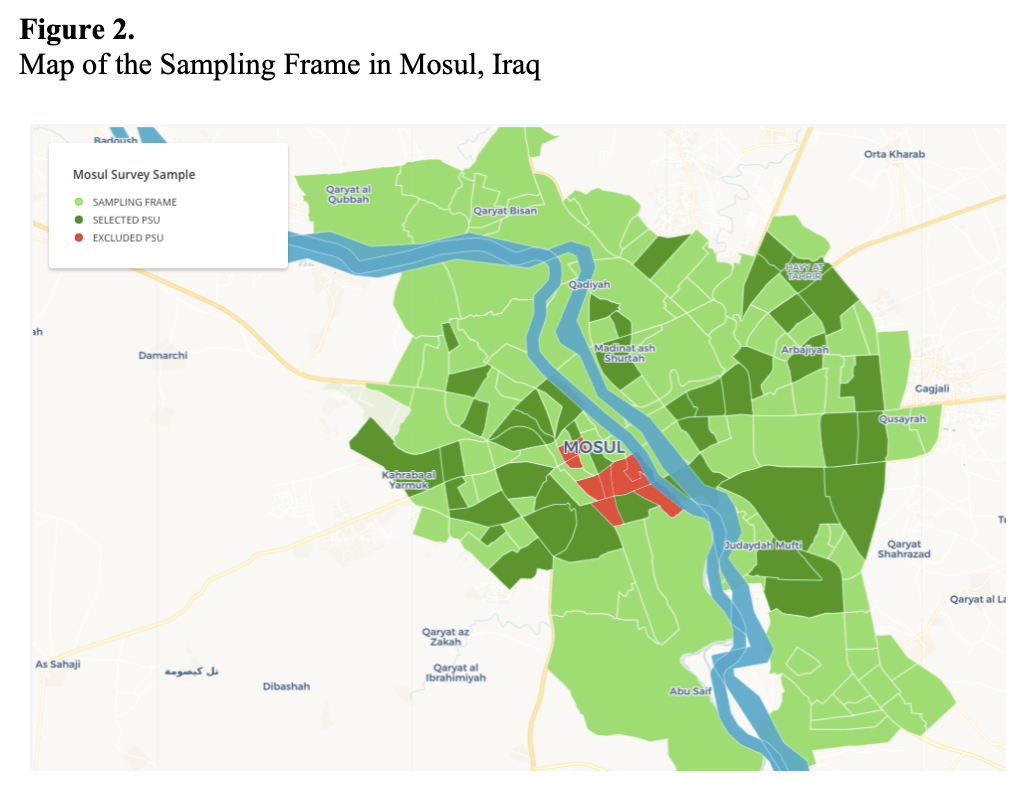

8. We conducted a survey experiment with 1,458 residents of Mosul, a city severely affected by IS's crimes (& still rebuilding when I last visited in Dec 2019), to understand how carceral vs. noncarceral sanctions affect participants' willingness to allow the return & ...

9. reintegration of hypothetical nonviolent IS "collaborators" into their neighborhood. We found:

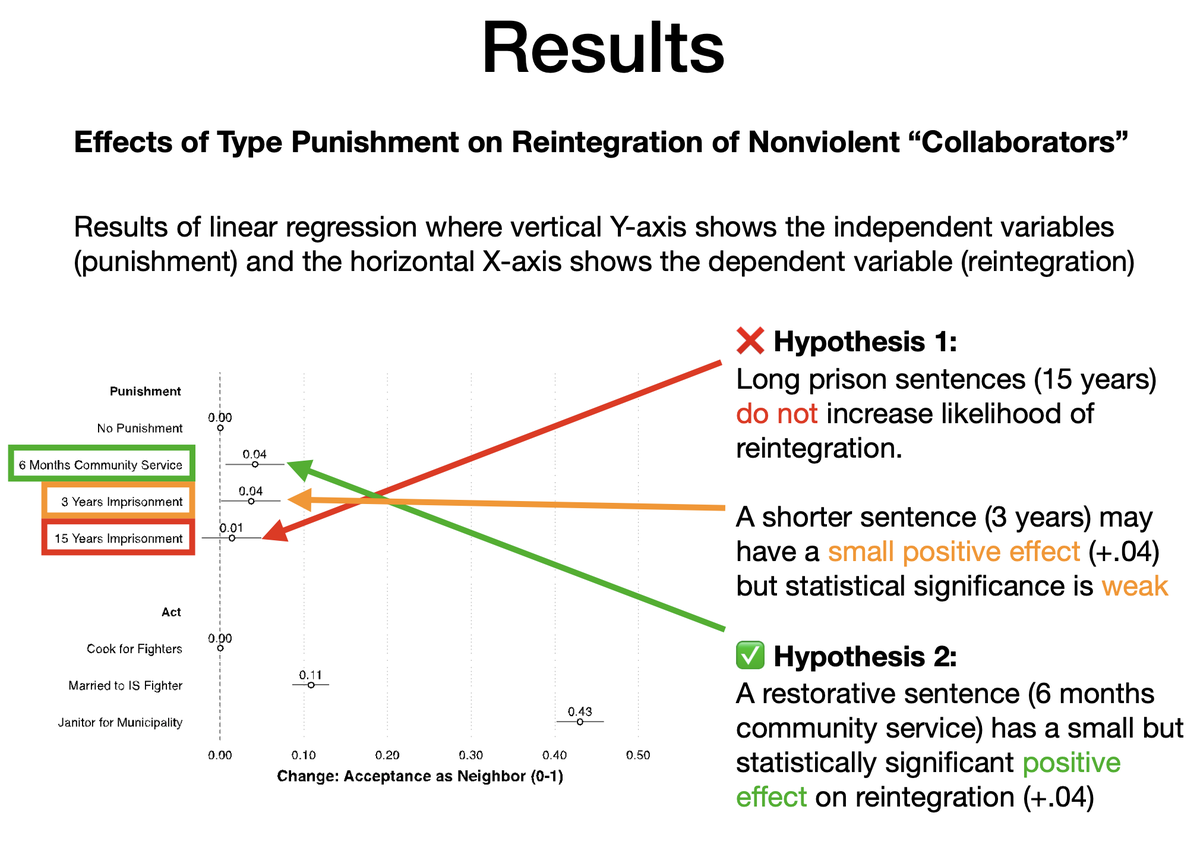

Long prison sentences (15 yrs) do not increase support for reintegration

Long prison sentences (15 yrs) do not increase support for reintegration

But a restorative noncarceral sentence (community service) has a small but significant positive effect

But a restorative noncarceral sentence (community service) has a small but significant positive effect

Long prison sentences (15 yrs) do not increase support for reintegration

Long prison sentences (15 yrs) do not increase support for reintegration But a restorative noncarceral sentence (community service) has a small but significant positive effect

But a restorative noncarceral sentence (community service) has a small but significant positive effect

10. Our strongest finding:

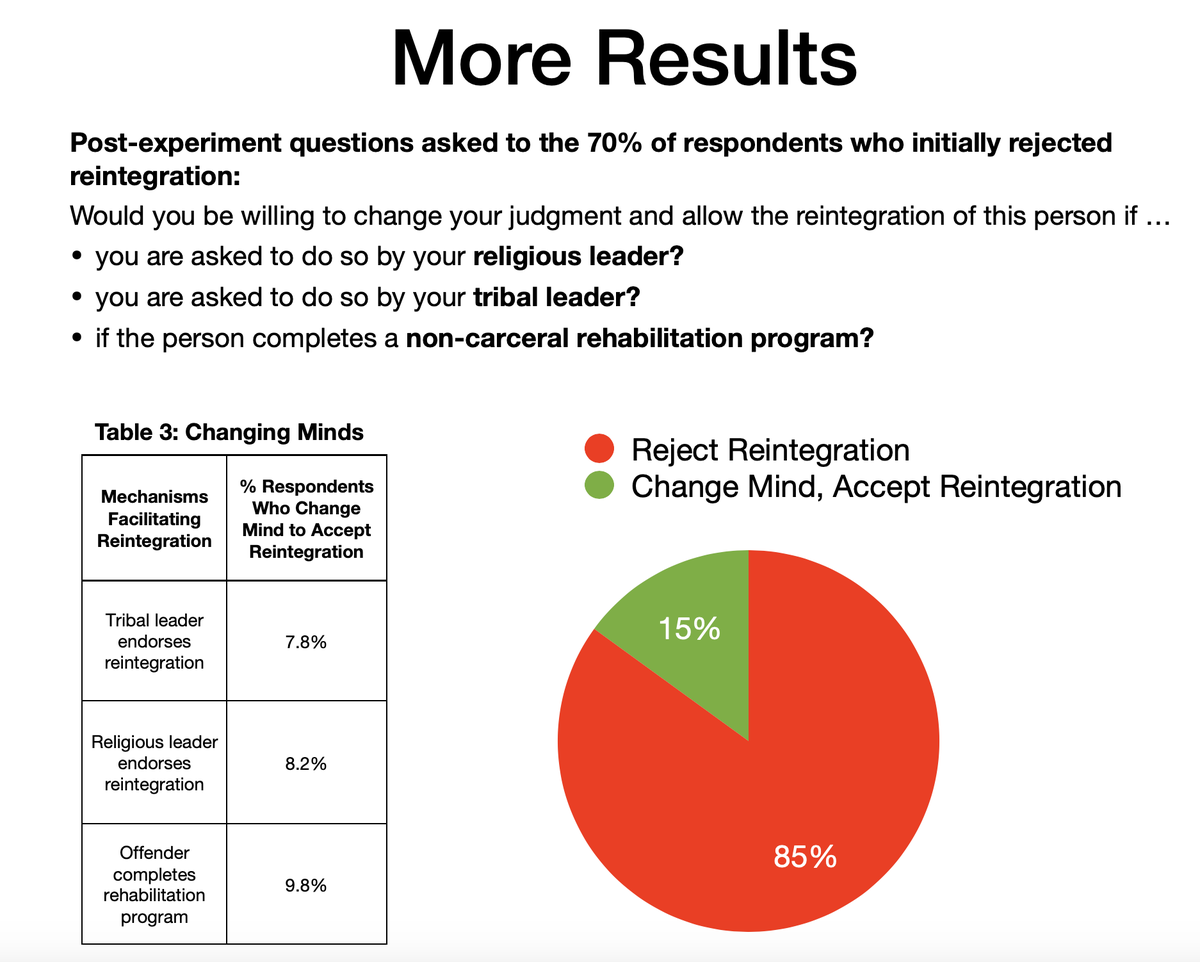

• Among the 70% of participants who initially rejected reintegration, a substantial 15% changed their mind & supported reintegration if encouraged by their religious or tribal leader or if the former offender completes a rehabilitation program.

• Among the 70% of participants who initially rejected reintegration, a substantial 15% changed their mind & supported reintegration if encouraged by their religious or tribal leader or if the former offender completes a rehabilitation program.

11. These results suggest that long-term incarceration does not—in this case—facilitate the important objective of eventual reintegration of former offenders & provide strong support for restorative and community-based justice mechanisms in #Iraq & potentially other contexts.

12. We also show how survey experiments, which are common in political science but not yet widely used by legal scholars, can help to address important questions about the causal effects of criminal justice policies on important outcomes including reintegration. Comments welcome!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter