New Working Paper

New Working Paper

Who Values Human Capitalists' Human Capital? Healthcare Spending and Physician Earnings

w @GottliebEcon @MariaAPolyakova Hugh Shiplett @UdalovaVictoria

Paper: https://kevinrinz.github.io/physicians.pdf

Summary: https://kevinrinz.github.io/physicians_summary.pdf

Slides: https://conference.nber.org/conf_papers/f141585.slides.pdf

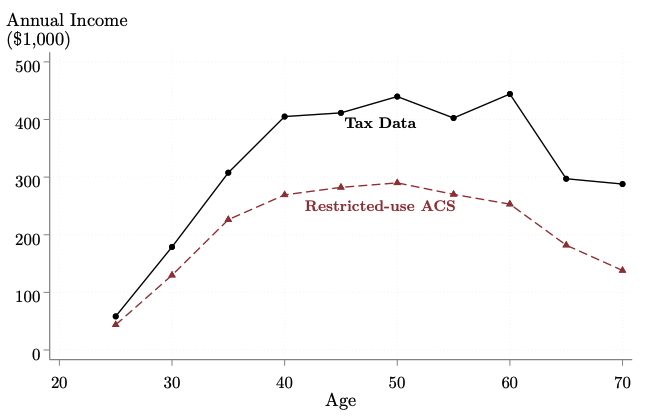

Physicians are obviously important in healthcare (billings make up 20% of national health expenditures), but they're also a big deal in public finance (top occupation in top 1%) and interesting in labor (human capital investment, rent-sharing). They're interesting!

Despite their clear significance, we don't have a good understanding of how much they earn, or of how government payments influence their earnings. This is in large part because many surveys are not well-equipped to measure top incomes.

We bring administrative data to bear on these questions. We identify physicians using the National Plan & Provider Enumeration System and attach income measures from W-2s and 1040s. The resulting dataset is very comprehensive & not susceptible to survey nonresponse/misreporting.

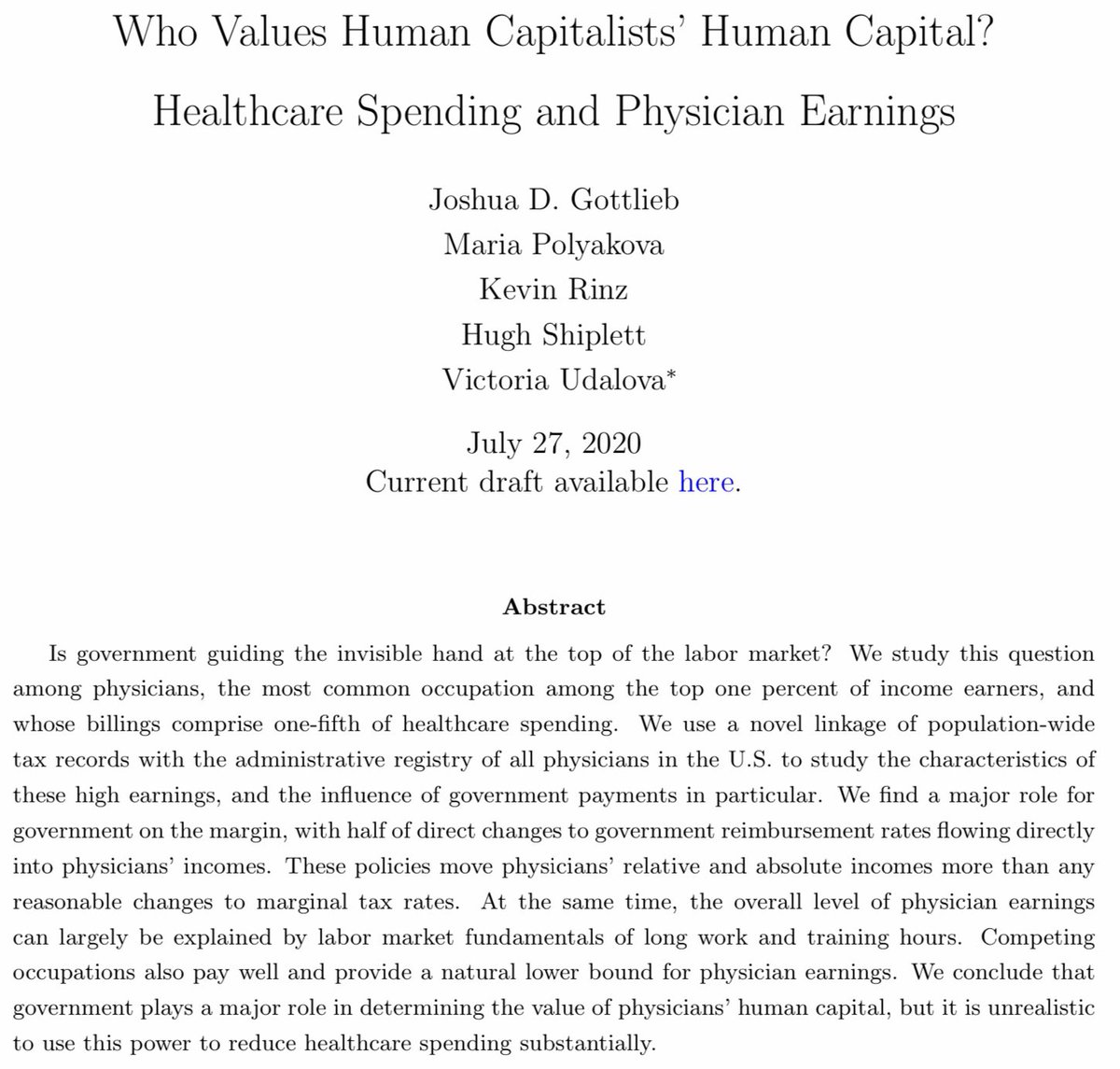

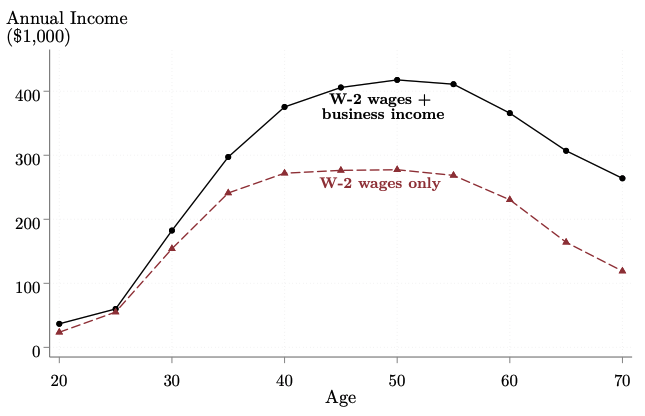

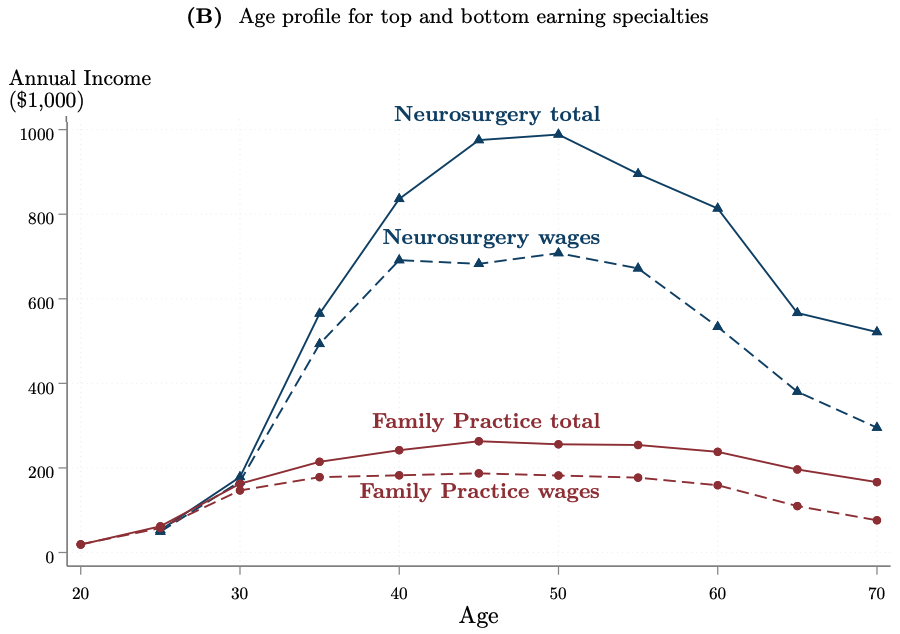

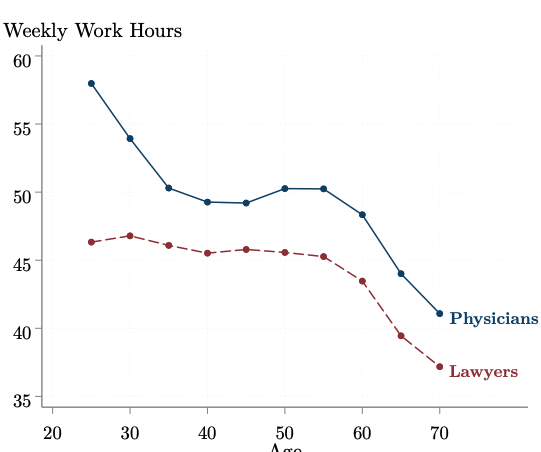

We find that physicians' earnings are high. The average physician earned $343,600 in 2017. The median physician made $255,200. Earnings grow quickly during physicians' 30s and peak in the late 40s - early 50s. Physicians in this age range averaged over $400,000 in 2017.

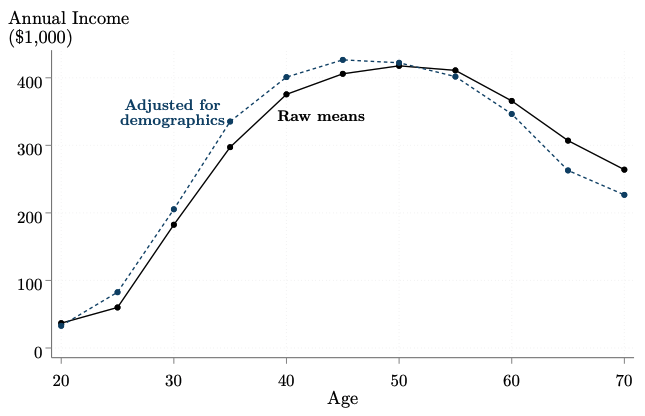

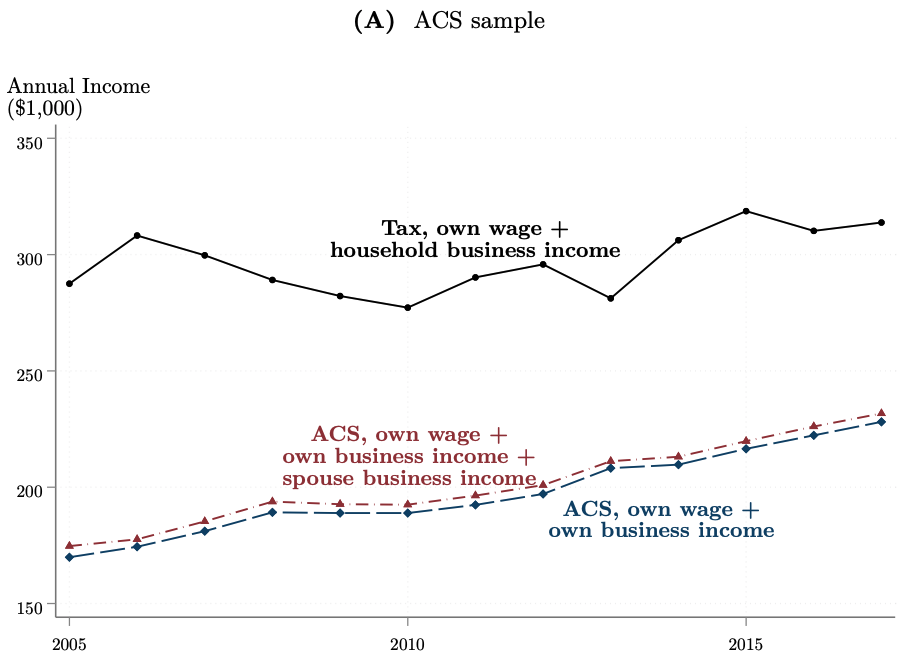

Notably, this is much more than we would have estimated physicians earned using the ACS. For people with both ACS and tax measures available, the ACS measure averaged only $237,000 in 2017. The gap between survey and tax measures is esp large at peak earnings ages.

The top 1% of physicians earn $3.9 million annually, more than 11x the average physician. 28% of physicians are in tax units that are in the top percentile of AGI, and another 24% are in the next percentile. Only about 13% are below the 90th percentile.

(Note that this, like everything else in the paper, is a descriptive point, not a normative or moral one. We're not saying physicians make too much, we're just saying what they make.)

Business income plays an important role in earnings growth after their 30s. Wages level off around age 40, but business income keeps growing. This likely also contributes to the gap between ACS and tax measures, since business income can be esp tough to measure w surveys.

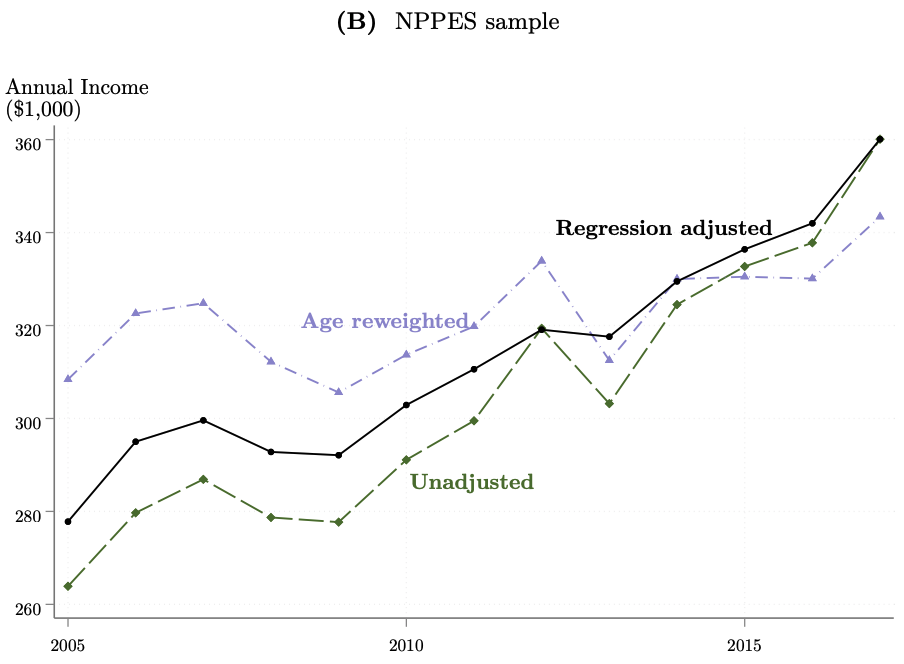

Changes in physician earnings over time are also interesting. Our analysis suggests that changing characteristics (esp age) of docs over time drive differences between trend for avg doc and trend for docs w/ given characteristics.

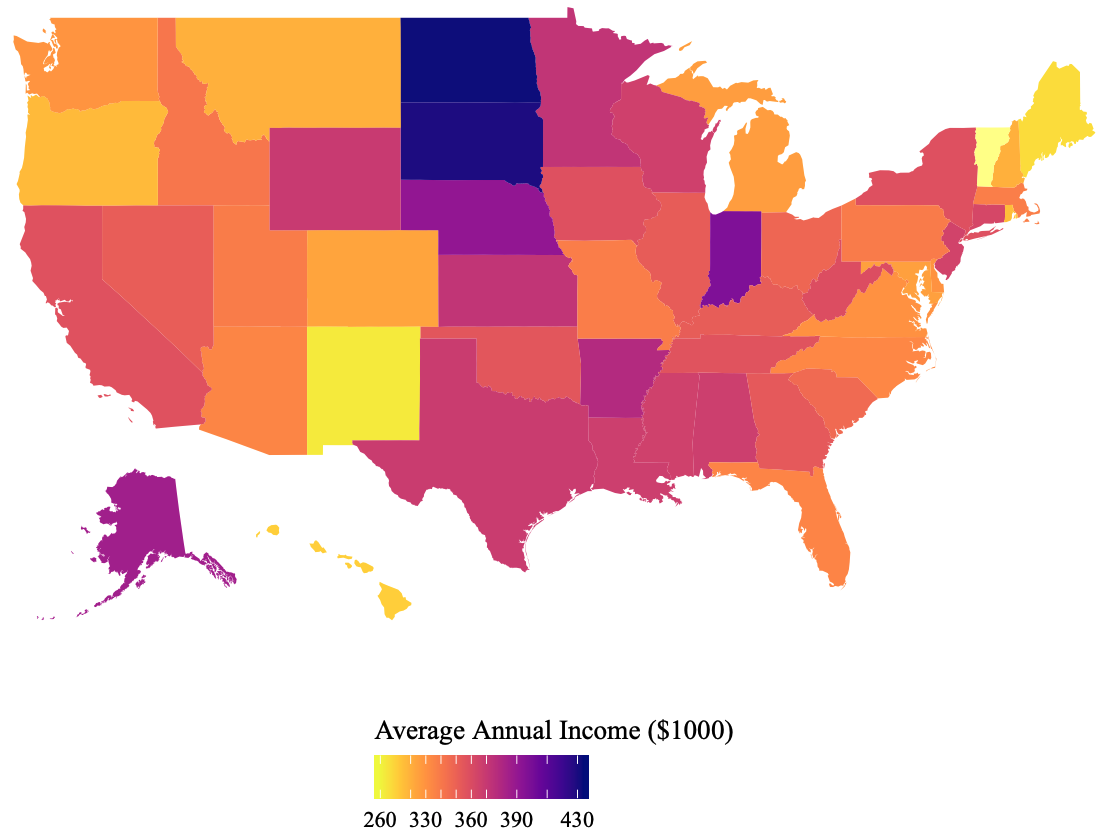

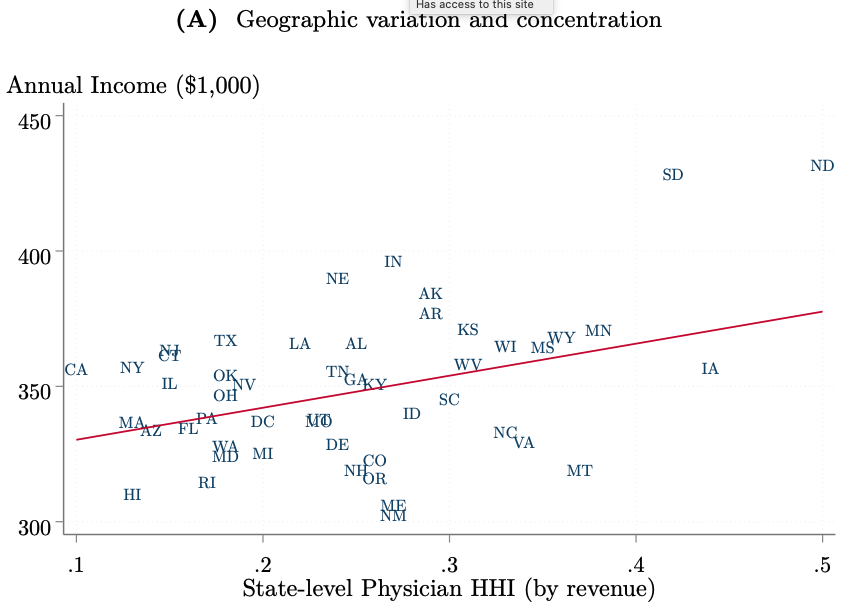

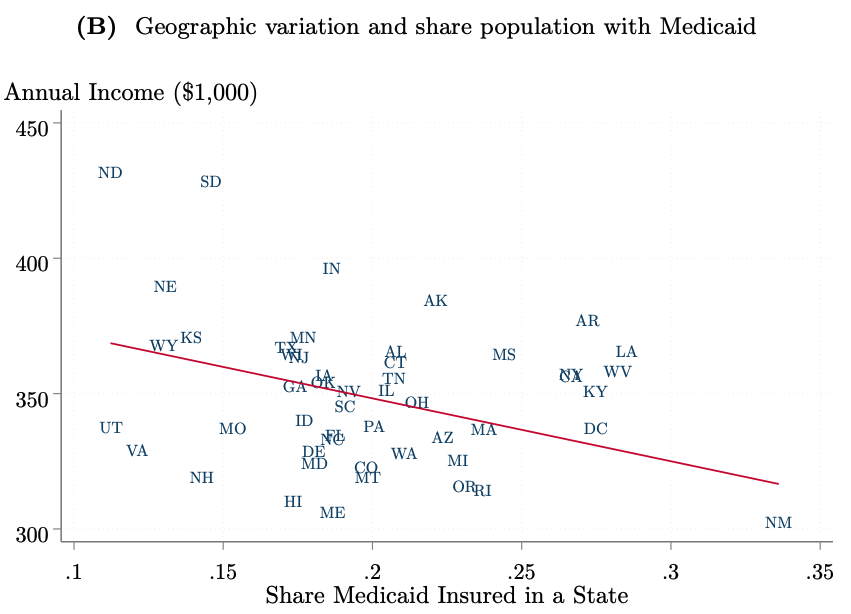

Geographically, physician earnings are highest in the Great Plains and the Deep South, while high-income coastal states have relatively low physician earnings. Earnings tend to be higher in states where markets are more concentrated, lower where more patients are on Medicaid.

As a bonus for researchers/interested data nerds, we've also published average physician earnings in commuting zone by specialty cells for the 125 largest CZs. Data and readme can be found here: https://kevinrinz.github.io/data.html

Have at it!

Have at it!

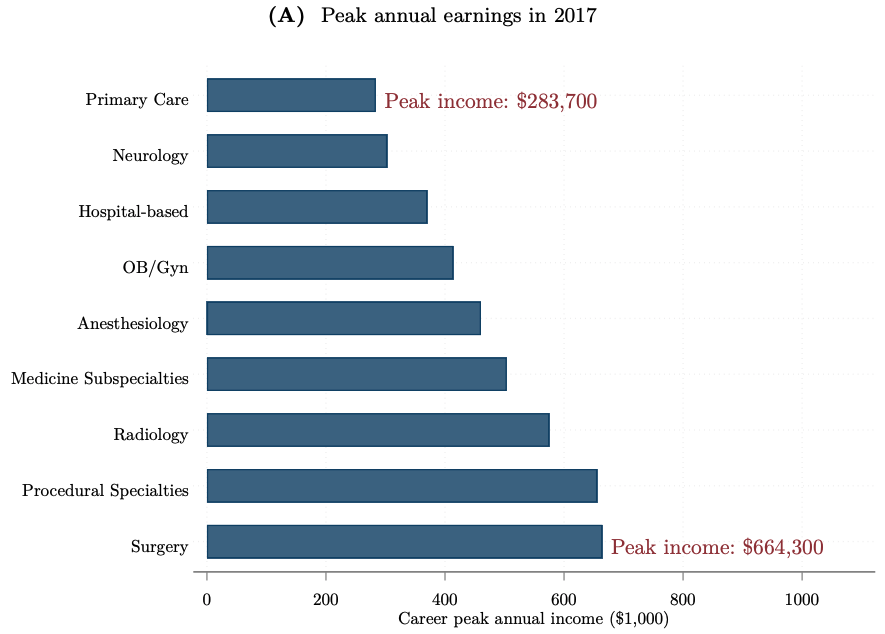

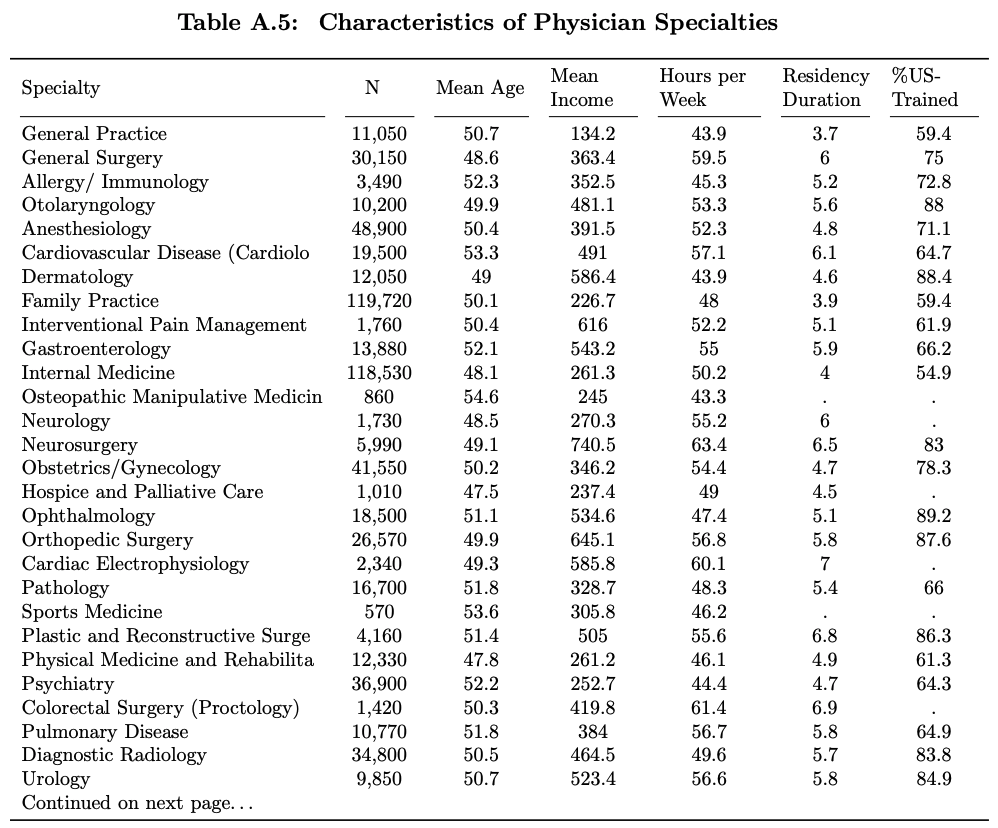

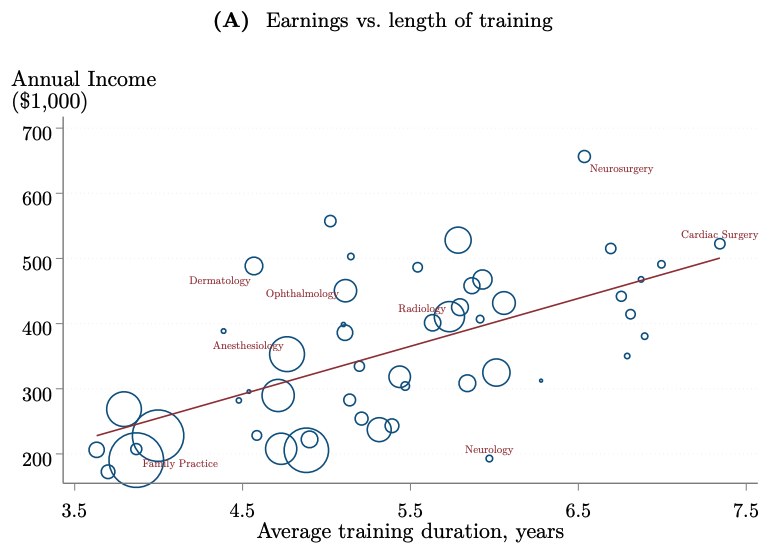

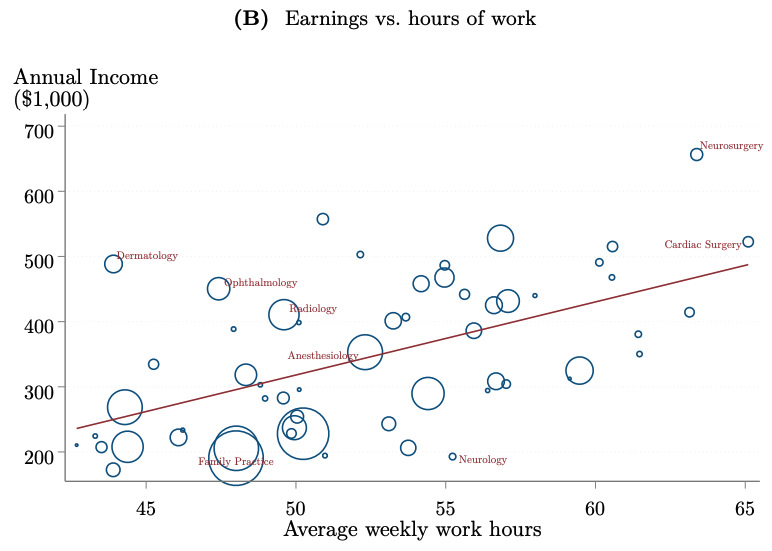

There are also large differences in earnings across specialties. Considering broad groups, peak earnings for surgeons were north of $600,000 in 2017, while primary care docs at peak earnings ages made less than $300,000. Differences in narrower specialties can be even starker.

There's also a long appendix table in the paper with more information on more narrowly defined specialties. Take a look!

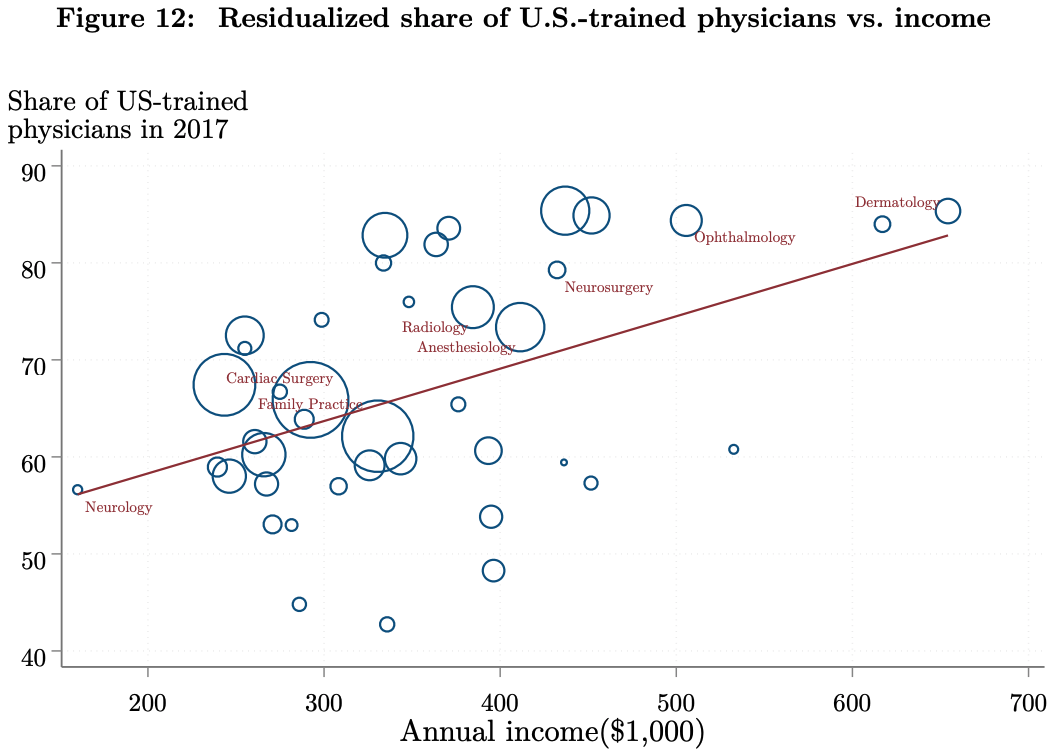

Some (but not all) earnings differences across specialties are associated with differences in length of training and hours of work. Earnings differences beyond those predicted by these variables are associated with a specialty being more attractive to US med school grads.

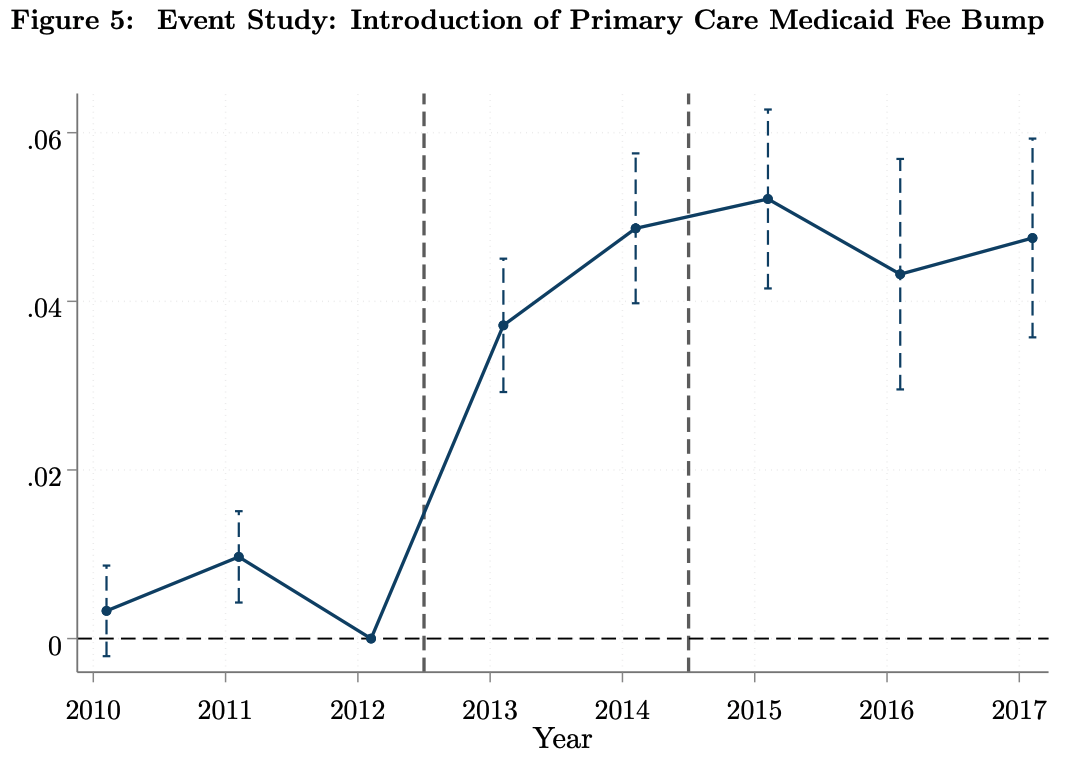

Next, we consider a 2013 change to Medicaid reimbursement rates for primary care physicians (PCP) to see how changes to government payments affect physicians' earnings. We find it increases PCP earnings by 4-5% relative to medicine subspecialists.

This increase in PCPs earnings amounts to about half of federal money spent on the fee bump, implying roughly 50% passthrough of the reimbursement change to physician earnings. The fee bump also moves 1.7% of PCPs into the top 1%.

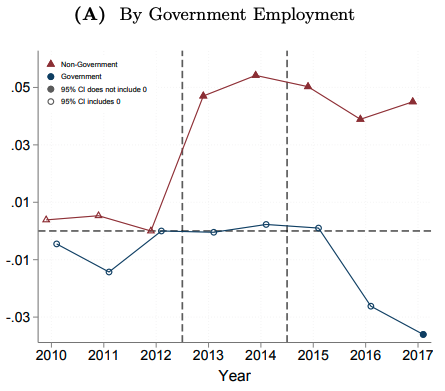

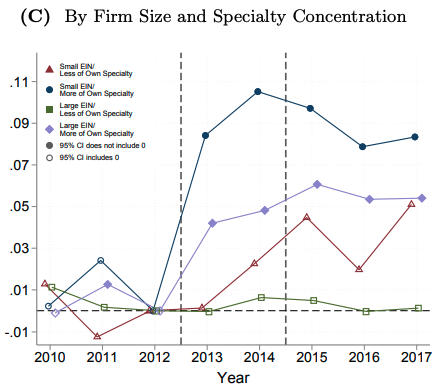

Considering heterogeneity, we find that physicians employed by government do not see increased earnings, while those who are self-employed or working in small practices largely with other PCPs see larger earnings increases. PCPs in diversified practices see smaller changes.

(We also consider the incidence of a Medicare Advantage change in the paper. More to come in this vein in future versions of the paper.)

Given how influential govt payments are on physicians' earnings, their position at the top of the income distribution, & large share of NHE dedicated to purchasing their services, one might wonder if changes to payments could reduce health spending and top income inequality...

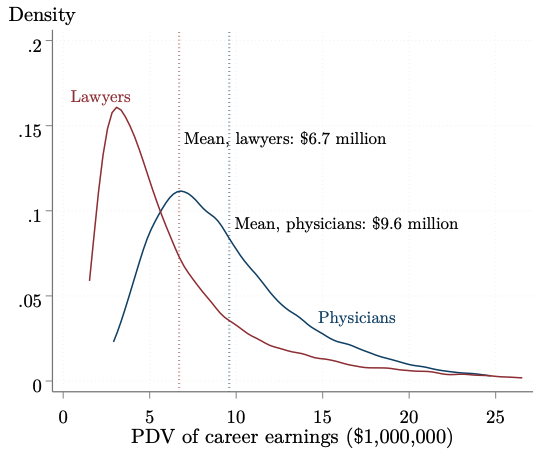

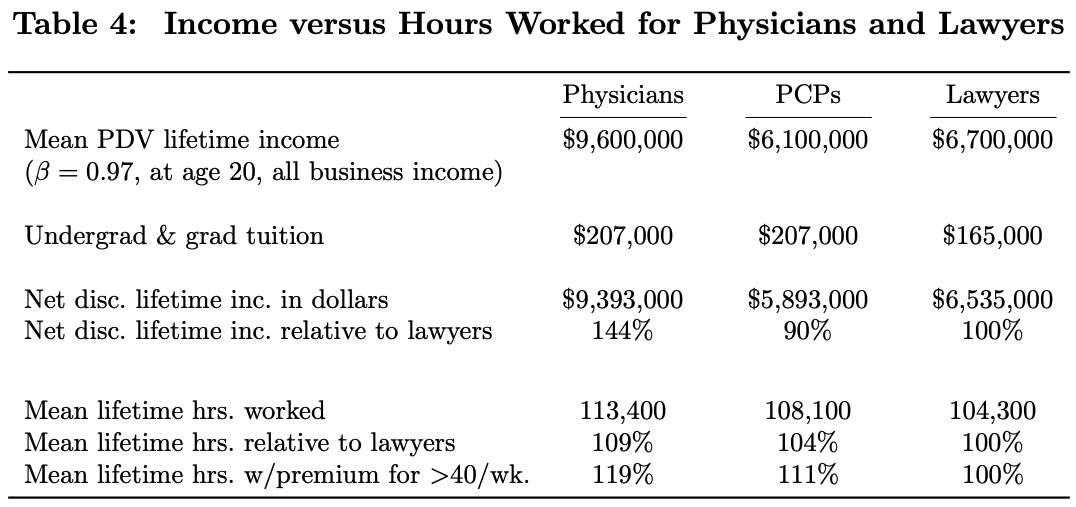

We consider a few different scenarios to get at this question. First, we compare physicians to lawyers, another occupation with high human capital investment and a reasonable approximation of physicians' outside option.

We estimate that physicians' career earnings, discounted at 3% to age 20, are $9.6 million. For lawyers, this figure is $6.7 million. After adjusting for differences in training costs and hours worked, physicians earn 25% more than lawyers over their careers.

Notably, direct training costs are small relative to earnings for physicians - tuition costs (incl interest on debt) amount to only ~2% of lifetime income on avg. Of course, this doesn't include opportunity cost of training. But say that doubles the total. Still a lot left over.

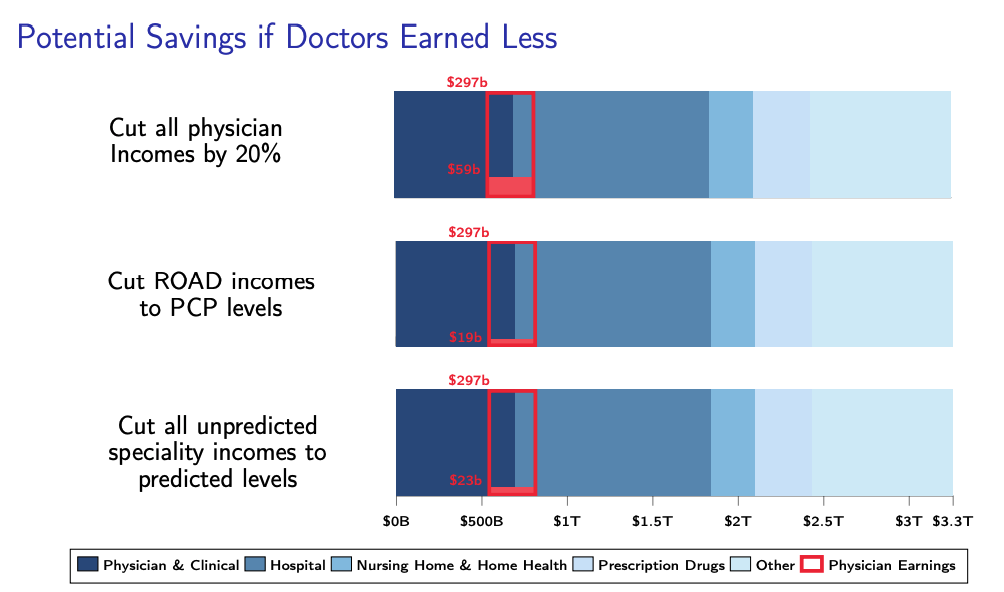

Cutting average physician pay to the level of average lawyer pay (which also happens to be roughly average PCP pay) could save about $59 billion (2% of NHE).

This also suggests savings would come from higher paid specialties. Cutting particularly high-paid "ROAD" specialties to PCP levels would save about $19 billion (0.6% NHE). Cutting all specialties to levels predicted by fundamentals saves a bit more.

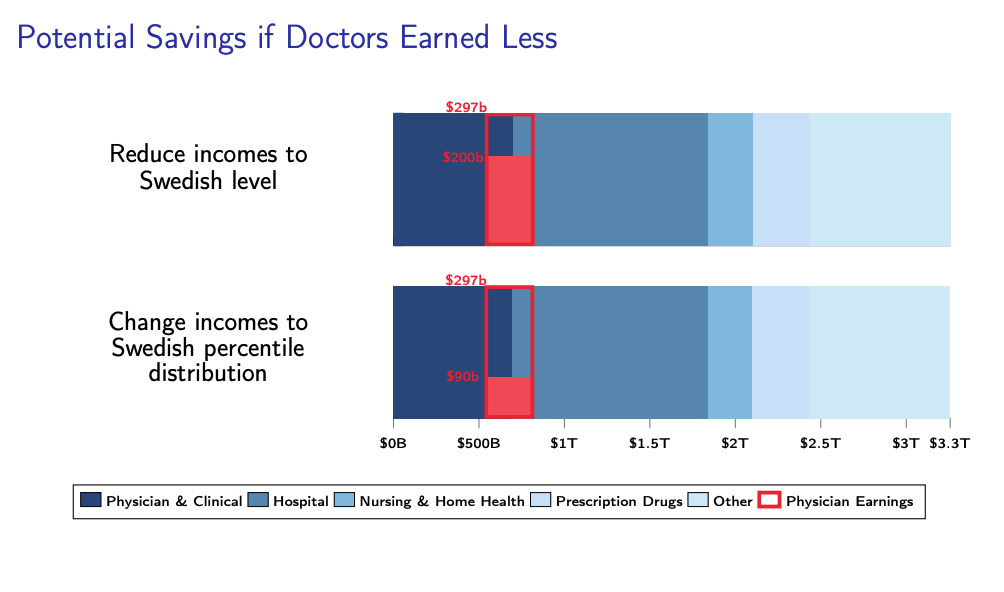

Aligning US physician earnings with physicians in other countries could potentially save somewhat larger amounts, but such cuts could prove more difficult to implement given the availability of other lucrative employment options in the US.

So, to sum up, government payments have a lot of influence on physicians' earnings, which are high, but not so much higher than what they might make in other jobs that there are enormous amounts to be saved by cutting reimbursements.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter