We don't "accept" car accident fatalities. We devote billions of dollars and untold effort every year to constructing laws, public policy, and physical infrastructure to bring them down. And it works. https://twitter.com/ClayTravis/status/1287768925711863813

"If we're so worried about preventable deaths, then why don't we do something about car crashes?"

My friend, the amount of science, engineering, and legislation devoted the design and construction of every inch of public road for exactly that purpose would blow your mind.

My friend, the amount of science, engineering, and legislation devoted the design and construction of every inch of public road for exactly that purpose would blow your mind.

Lights. Reflectors. Rumble strips. Roadway materials. Guardrail design. Signage. Regulation of the crown of the road and the angles of curves. Passing lanes. Lane markers. Speed limits. Size and composition of shoulders and medians.

And that's just the stuff that I, a rando humanities professor who doesn't own a car, could think of off the top of my head in a minute and a half.

(And yes, that's just the roadway itself. Car design is a whole other issue, as is regulation and licensing of drivers.)

(Having a dad who's an urban planning professor is a wonderfully instructive experience. I recommend it.)

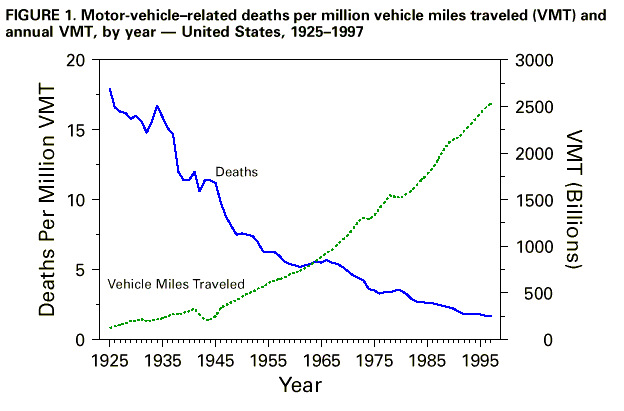

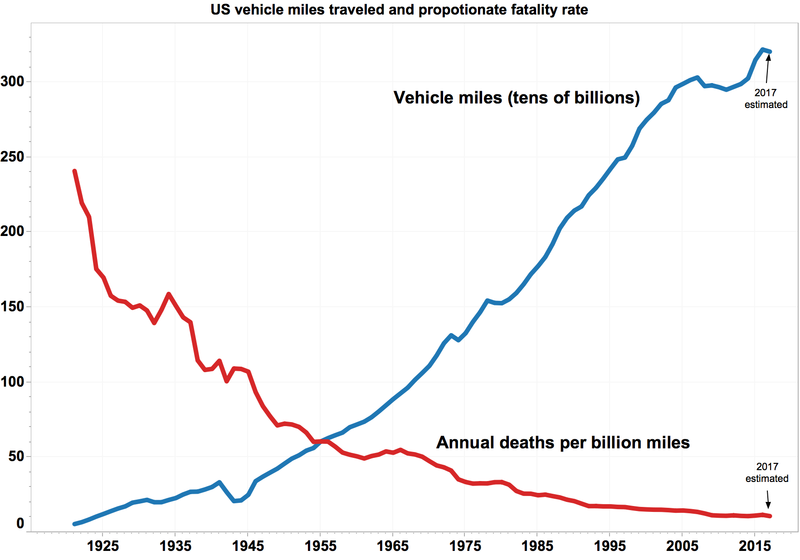

And no, to say we devote huge amounts of resources to reducing auto fatalities isn't to say that we're doing all we could or should be doing. There's all sorts of stuff we should be doing that we're not doing. And yet:

That's the turned-down guardrail end, if you're wondering—a huge step forward in guardrail design at the time, though largely superseded by even better technologies in the last few decades. More here: http://www.crashforensics.com/papers.cfm?PaperID=53

BTW, some folks in my mentions are noting that deaths-per-mile haven't been falling much in the US in the last few years, and have actually been rising some years. Again, though, we can look to policy choices for explanations. (SUV-friendly policies, for instance.)

There are always going to be competing imperatives in public policy, and powerful bad actors pushing for policies that lead to outcomes not in the public interest. The struggle to get good policies adopted is real, and hard.

But our roads and cars are dramatically safer than they were fifty years ago, and that didn't just happen by accident, by magic, or through the invisible hand of the market. It happened through the dogged pursuit of good public policy—by policymakers, activists, and engineers.

So many of these victories are largely invisible. Others are dramatic when they happen, but forgotten within a few years. But added together, they amount to millions of lives saved, families preserved, tragedies averted.

Several people have replied to this thread saying that while yes, we engage in all sorts of mitigation strategies around auto accident fatalities, we still drive, suggesting that anti-COVID measures are the equivalent of eliminating all cars.

There are a bunch of problems with that analogy, but the biggest is that it neglects the distinction between a long-term problem and a short-term crisis.

If we discovered a catastrophic new defect in the interstate highway system that could be fixed by shutting down the entire system for two months, but was going to kill more than a thousand additional people every day until we did, we'd shut the system down for repairs. Period.

The question wouldn't be whether we should we shut down the interstates, it would be how we could best mitigate the effects of doing so, and solve the local crises that were likely to develop as a result of the shutdown.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter