Episode 10 of #DeafHistorySeries is on Annie Jump Cannon (1863-1941), the “Computer” whose work mapped the field of astronomy and impacted the way the sky is seen.

Annie Jump Cannon was born in Dover, Delaware on 11 December 1863, the eldest of three children born to Wilson Lee Cannon and Mary Jump.

Wilson was a shipbuilder and state senator who had four children with his first wife Ann Scotten. Mary was an amateur astronomer.

Wilson was a shipbuilder and state senator who had four children with his first wife Ann Scotten. Mary was an amateur astronomer.

In her adolescent years, Mary took astronomy classes at Quaker Friend’s School near Philadelphia. She passed her love of star-gazing to Annie, fashioning a makeshift observatory in their attic.

As a child, Annie spent days studying the constellations & reading astronomy books.

As a child, Annie spent days studying the constellations & reading astronomy books.

Wilson & Mary nourished Annie’s love of learning. Mary especially encouraged her to study science and mathematics & aim for higher education.

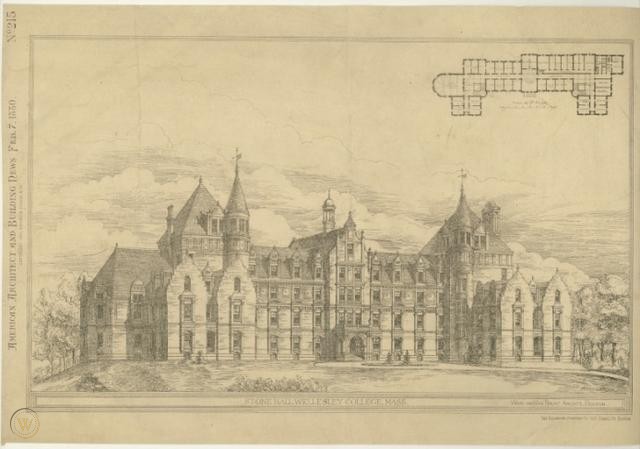

In 1880, Cannon became the first woman from Delaware to leave for college, enrolling at Wellesley College in Massachusetts.

In 1880, Cannon became the first woman from Delaware to leave for college, enrolling at Wellesley College in Massachusetts.

Women at the time were expected to marry & stay within their homes. Education, it was believed, would weaken their constitution.

The rise of “Seven Sisters” colleges from 1865-1889 made higher education a dignified goal for upper-class women. Many choose to study the sciences.

The rise of “Seven Sisters” colleges from 1865-1889 made higher education a dignified goal for upper-class women. Many choose to study the sciences.

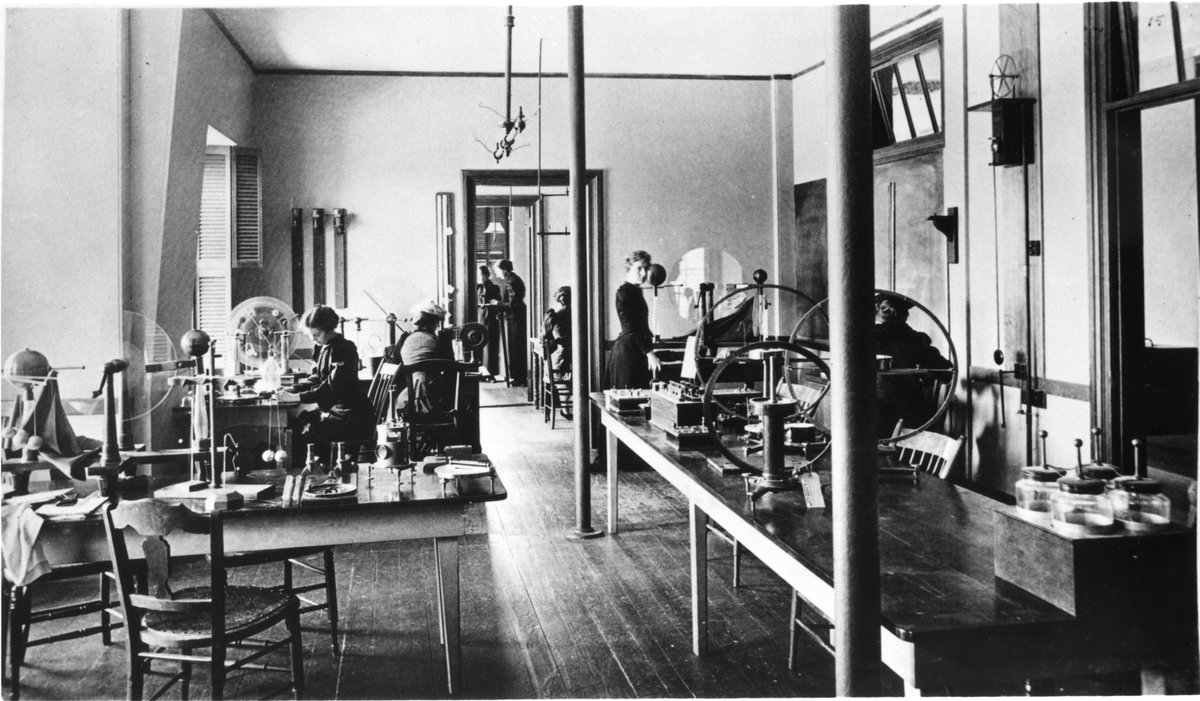

At Wellesley, Cannon studied physics under Sarah F. Whiting (1847-1927), the college’s first professor of physics (pictured). It was Whiting who introduced Cannon to astrological spectroscopy—the study of stars using electromagnetic radiation to identify their properties.

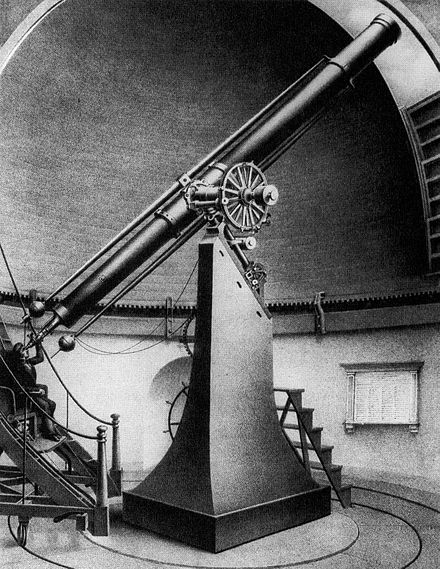

After Edward Charles Pickering (1846-1919), the Director of Harvard Observatory invited Whiting to visit and work with the telescope, Whiting ensured no astronomical event would pass without her students witnessing it.

Whiting even showed Cannon how to use a four-inch telescope to observe the Great Comet of 1882.

“Morning after morning,” Cannon wrote in her eulogy of Whiting in 1927, “she marshalled the girls to balcony or porch to see the Great Comet…in all its splendor.”

“Morning after morning,” Cannon wrote in her eulogy of Whiting in 1927, “she marshalled the girls to balcony or porch to see the Great Comet…in all its splendor.”

At Wellesley, Cannon's hearing declined, likely due to damage from winter exposure. Scarlet fever in 1893 worsened her deafness; by middle-age she was nearly completely deaf. One of her brothers also became deaf, giving some indication Cannon had progressive hereditary deafness.

Throughout her life, Cannon managed her deafness by speechreading and favoring one-on-one conversations. She even obtained one of the early Acousticon hearing aids to assist her in more lively social situations when needed.

(Picture: ad for Acousticon, 1906)

(Picture: ad for Acousticon, 1906)

Cannon graduated in 1884 as valedictorian of her class, returning to Dover & keeping busy with reading clubs & tutoring.

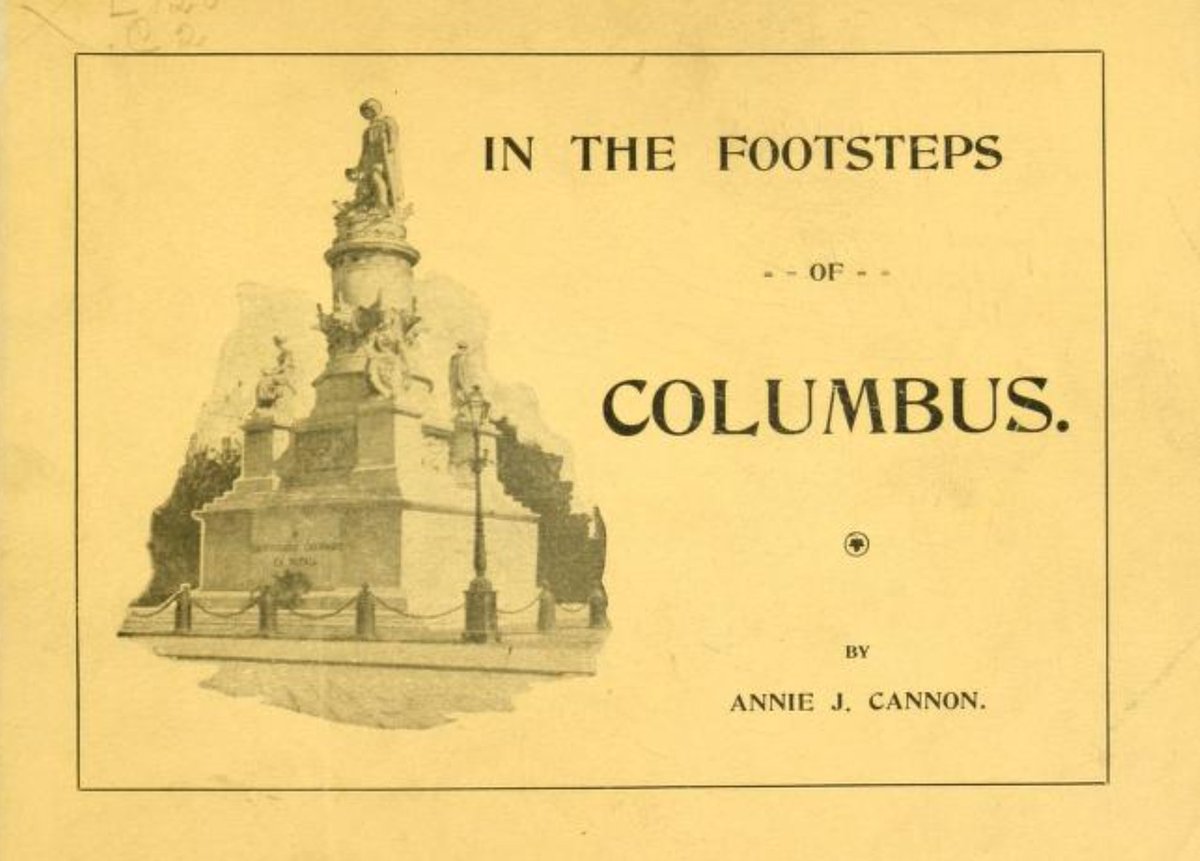

In 1892 she visited Europe to photograph a solar eclipse, compiling her work as a booklet to sell at the 1893 Columbian Exposition.

https://archive.org/details/infootstepsofcol00cann/page/n4/mode/2up

In 1892 she visited Europe to photograph a solar eclipse, compiling her work as a booklet to sell at the 1893 Columbian Exposition.

https://archive.org/details/infootstepsofcol00cann/page/n4/mode/2up

A year later, Mary Jump Cannon died, leaving her daughter without her closest intellectual companion.

Unable to stay in Dover and be surrounded by her mother’s memories, 10 years after graduation Cannon returned to Wellesley College, reaching to her former professors for work.

Unable to stay in Dover and be surrounded by her mother’s memories, 10 years after graduation Cannon returned to Wellesley College, reaching to her former professors for work.

Whiting helped Cannon procure an assistantship conducting X-ray experiments in the physics lab. Cannon taught physics & took graduate courses in astronomy & physics.

She would eventually obtain her masters from Wellesley College in 1907.

She would eventually obtain her masters from Wellesley College in 1907.

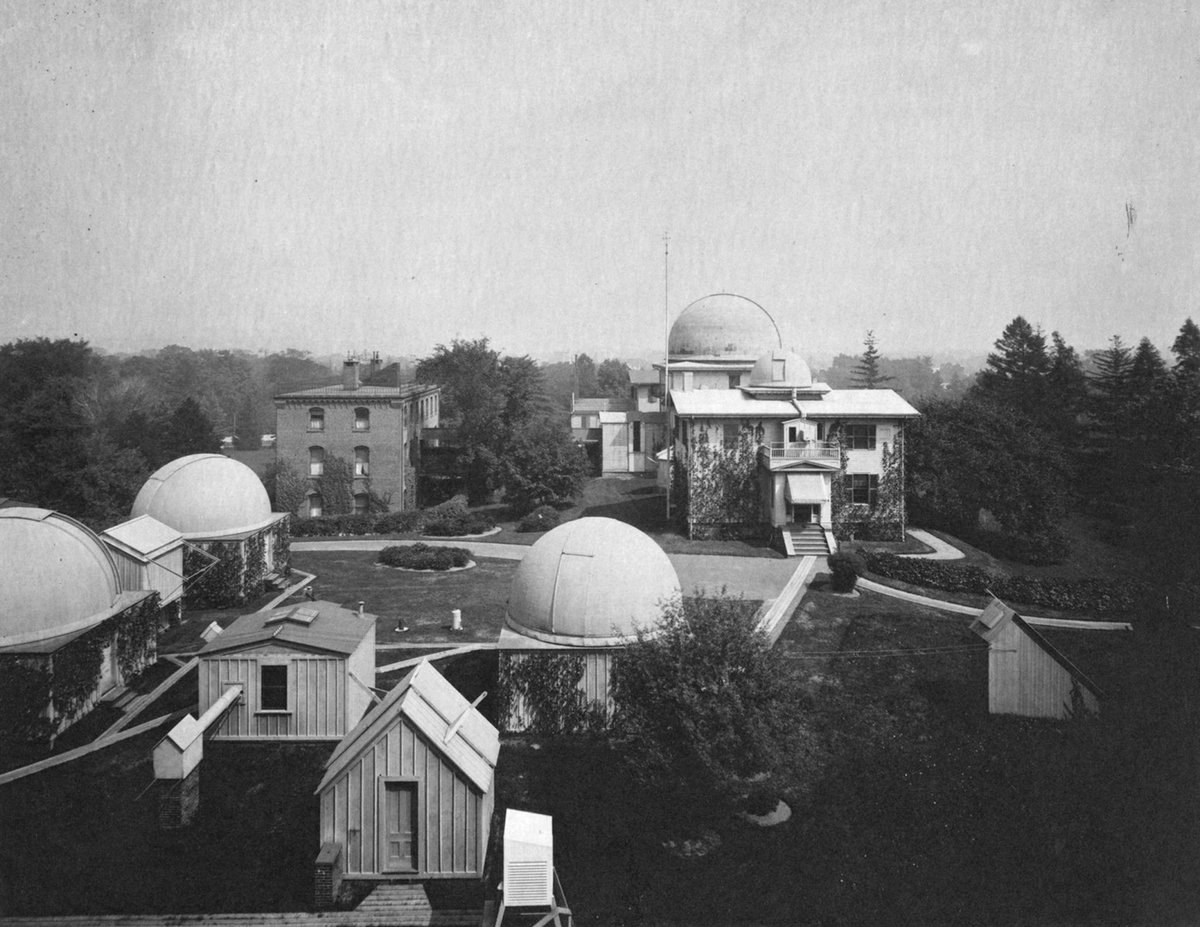

Cannon also connected to Pickering, who offered her an unpaid internship at Harvard Observatory. As the Observatory gained fame for its photographic research, Cannon transferred to Radcliffe College in 1896 as a “special student” to work with more powerful telescopes.

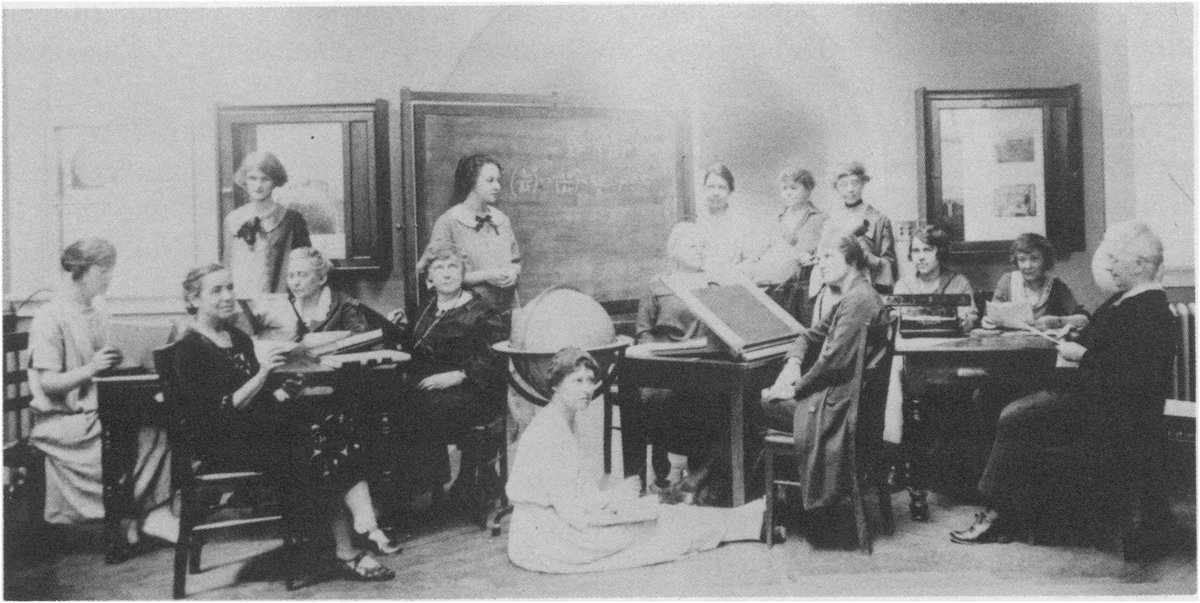

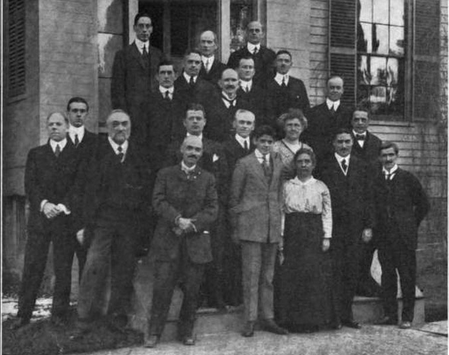

At the Observatory, Cannon joined “Pickering’s Women,” the nickname for the group of female astronomers hired by Pickering to complete the Henry Draper Catalogue—an extensive effort to provide the positions, magnitudes, & spectra of more than 225,330 stars using astrophotography.

The women analyzed the observatory data, essentially performing as “human computers.” They were also cheaply paid, making 25 to 50 cents hourly despite the complexity of their work. They worked on atmospheric refraction, classified stars, and cataloged photos and star charts.

Cannon’s early years at the Observatory were spent studying variable stars, recording slight fluctuations in brightness.

She worked alongside prominent astronomers, including Williamina Fleming, Cecilia Payne, Antonia Maury, and Henrietta Leavitt (pictured)--who was also deaf!

She worked alongside prominent astronomers, including Williamina Fleming, Cecilia Payne, Antonia Maury, and Henrietta Leavitt (pictured)--who was also deaf!

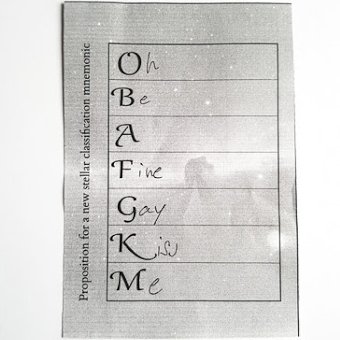

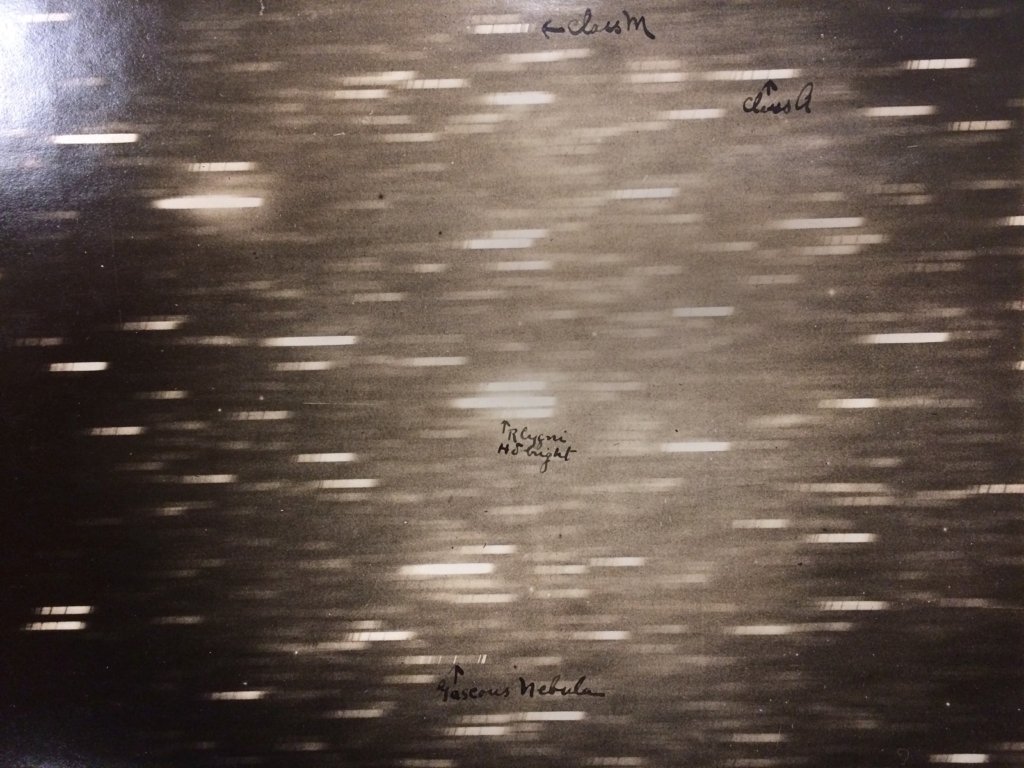

While working, Cannon found the conventional systems of star classification ineffective. Stars are classified based on their spectra—the lines that interrupt the rainbow of colors by splitting light with a prism. Each line corresponds to a different chemical makeup in the star.

Based on the thickness of the lines on a star’s spectrum, Cannon created a new system with seven classes—O, B, A, F, G, K, M. She realized that the stellar temperatures also determined spectral lines: O stars are hot and blue; M stars are cool and red. Her system is still used.

In 1911, Cannon became the curator of astronomical photographs at Harvard Observatory.

Her work was effective as she could classify three stars/minute. Pickering praised her speed in 1927: “Miss Cannon is the only person in the world—man or woman—who can do this work quickly.”

Her work was effective as she could classify three stars/minute. Pickering praised her speed in 1927: “Miss Cannon is the only person in the world—man or woman—who can do this work quickly.”

Cannon classified more than 225,000 stars. Her work was published in the Draper Catalogue. She also discovered 300 variable stars and 5 novae (exploding stars).

See more about her work with stellar spectra: https://library.cfa.harvard.edu/cannon-spectroscopy?admin_panel=1

See more about her work with stellar spectra: https://library.cfa.harvard.edu/cannon-spectroscopy?admin_panel=1

In 1923, the National League of Women Voters declared Cannon one of 12 greatest living women. Two years later, she received an honorary Doctor of Science from Oxford, the first women in its 300-year history. Cannon received many other honorary degrees, including from @udelaware.

Though a popular collaborator & friend, some American eugenicists (e.g Raymond Pearl) considered Cannon “defective” due to her deafness & prevented her from being nominated to the National Academy of Sciences.

In 1931, she became the first woman awarded the Henry Draper Medal.

In 1931, she became the first woman awarded the Henry Draper Medal.

A year later, Cannon was awarded the Ellen Richards Research Prize from the Association to Aid Scientific Research. After giving the $1000 prize, AASR dissolved the award, explaining that women had finally achieved equal research opportunities as men.

Cannon disagreed, arguing more scientific support for women was needed.

She used her award to endow the Annie Jump Cannon Prize for women astronomers, which is still given every 3 years by the American Astronomical Society. Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin (1900-1979) was first winner

She used her award to endow the Annie Jump Cannon Prize for women astronomers, which is still given every 3 years by the American Astronomical Society. Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin (1900-1979) was first winner

Cannon continued working, even travelling to Arequipia, Peru, to photograph stars near the South celestial pole. In 1938, after 40 years of work, she finally received a permanent position at Harvard, retiring two years later.

She died in April 1941.

She died in April 1941.

Further Reading:

Dava Sobel, THE GLASS UNIVERSE (2017)

Natasha Geiling, “The Women Who Mapped the Universe and still couldn’t get any respect” https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-women-who-mapped-the-universe-and-still-couldnt-get-any-respect-9287444/

Norah H. Murphy, “Eyes to the Sky” https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2017/5/5/annie-jump-cannon/

Galactic Gazette: https://wolba.ch/gazette/ajc/

Dava Sobel, THE GLASS UNIVERSE (2017)

Natasha Geiling, “The Women Who Mapped the Universe and still couldn’t get any respect” https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-women-who-mapped-the-universe-and-still-couldnt-get-any-respect-9287444/

Norah H. Murphy, “Eyes to the Sky” https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2017/5/5/annie-jump-cannon/

Galactic Gazette: https://wolba.ch/gazette/ajc/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter