Finally have the time and the brain space to sit down with this talk on Sex Work as Queer History. I'm pretty excited to hear more about this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=wtVBczKi3ZY

Melissa Grant contextualising the discussion of how sex workers have shaped the fight for queer rights and what this might mean for queer politics. She notes that sex worker rights have been part of every major rights movement in North America.

While the sex worker rights movement is gaining more mainstream recognition now, it has a long history that is essential to remember and use to resist the santising of rights movements and also of historical records.

Melissa Grant notes that although this discussion occurs during Pride, we should note that sex working people have shaped queer rights long before the events at Stonewall (though Stonewall is commemorated as the basis for Pride taking place during this time in North America).

Hugh Ryan noting that the increasing focus on Stonewall, and specifically on its first night, risks obscures the queer politics and militancy that existed not only alongside of it in other parts of the Village, but also events that happened before or after (eg. The Haven riots).

Ryan talking about what happened during Stonewall at the Women's House of Detention (a women's prison that no longer exists; 1932-1974). These women prisoners rioted in solidarity with the people on the outside, despite the likelihood of violent retribution from the guards.

He notes that there are records that they screamed "gay power!" and set some of their belongings on fire and threw them out of windows, yet this solidarity is erased somehow within the currently constructed Stonewall narratives.

Rita Mae Brown is one of the people who notes this. He notes that all the records of the period get written up by men so the solidarity of the women's prison gets lost in this. Notably, most of the people in that prison were there for sex work related charges during that period.

Many were queer, many were political activists. One of the women in that women's prison during that first night at Stonewall was a Black Panther, Afeni Shakur. Following this she meets members of the Gay Liberation Front who write about this meeting afterwards. (Solidarities!)

He's recounting the Gay Liberation Front's recounting in which there is a discussion of how Afeni Shakur becomes aware of the processes of queer liberation and its necessity. She took this knowledge with her and intended to create solidarity & address homophobia in the BPP.

(Side note: I'm really enjoying learning more about the 1970s history of the Black Panthers that isn't about the men but more focused on the women.)

Shakur worked with radical queer women and early trans journalists to create solidarities between the Black Panther Party and the emerging queer rights movement, understanding that these were all connected in a need to end oppression.

Cecilia Gentili is recounting her history in Argentina. She notes the first time she met a trans person and found this to be such an affirming revelation because now she could see other people like her that existed around her. (Community matters! Trans elders and peers matter!)

( #CW discussion of #DrugUse)

She's talking about the way in which trans lives in Argentina were positioned at that point, having to acknowledge the likelihood that trans women would go into sex work, potentially use drugs, and die young.

She's talking about the way in which trans lives in Argentina were positioned at that point, having to acknowledge the likelihood that trans women would go into sex work, potentially use drugs, and die young.

She's talking about Argentina's histories of dictatorships and democracies, & the ways in which these factored into trans oppression, particularly by the police. She notes with surprise that some of her friends who were able to prove police brutality are now getting reparations.

She can't believe that it's real that South America is paying trans women a pension as reparations for police brutality. It isn't something she thought would happen. (Honestly, I don't think this would happen here in India ever. AMAZING! More power to those women!)

She's recounting her coming to sex work as more necessity than choice, particularly as a trans woman, and taking sex seriously as profession. She notes it was a revelation that sex work was natural and empowering and allowed her practical ways to pay rent.

In the face of the rest of the world being #transphobic as heck, sex work allowed her a space as a trans teenager wherein she could feel valued and where her body and personhood wasn't positioned as "wrong." So this allowed for personal validation and economic survival.

She's discussing the power differentials within the queer community now, noting the power of gay men over trans women. This could be as basic as gay men conferring social capital (and being positioned as the ones who COULD confer social capital).

Continuing to talk about the ways in which exclusion, queerness, and sex work have functioned, Melissa Grant notes asks Red Schulte to speak to their understanding of the ways in which even these communities (queer and/or sex worker) can be exclusionary to certain identities.

(So much of this is making me think of that great article I read about the ways in which the leglisation of sex work is only about the idealised cis able-bodied white woman sex worker who participates in framing sex work as a morally wrong "choice" to eventually be opted out of.)

I can't find the article but I did find this other talk I watched last month about sex work, art, community, and decriminalisation which I thoroughly rec. I don't know if the video went up eventually but I did a livetweet at the time: https://twitter.com/SamiraNadkarni/status/1268336267202138112

So back to the talk! Red Schulte is talking about the ways in which hustling and the gender question (work/ marketing/ presenting of selves) can allow for validation, affirmation & community, but also have the darker side with the #dysmorphia, #anxiety tension & frustration of it

They are talking about anchoring the discussion of queer sex workers in a history of communities of care and mutual aid. They note that sex workers have been fetishised by the policing industry in the country for at least a century: in policy, in their personal lives, in practice

This is hyperfocused on Black & immigrant sex workers. As a result, sex workers have a lot to say about the violence of "rescue," of white saviourism that gets wrapped up in criminalisation, and these histories of violent fetishization.

In actively refusing these violences, sex workers (particularly Black and migrant sex workers) have created knowledges for harm reducing and community building care networks. This allows for care networks outside of the purview of the state.

As a side note, sex workers have long been at the forefront of the abolition movement. If anyone is interested in readings around this or a reading group, here's a recommendation: https://twitter.com/SexWorkHive/status/1277991511389614080

Also, instead of my livetweet thread further up, just watch the video. I finally found it! https://twitter.com/MoMAPS1/status/1272940580763578370

Important note: Just so it's clear, the abolition mentioned is the abolition of violent systems/institutions, not the abolition of sex work. The latter is part of moralising and criminalising structures that endanger sex workers and act against their interests. Sex work is work.

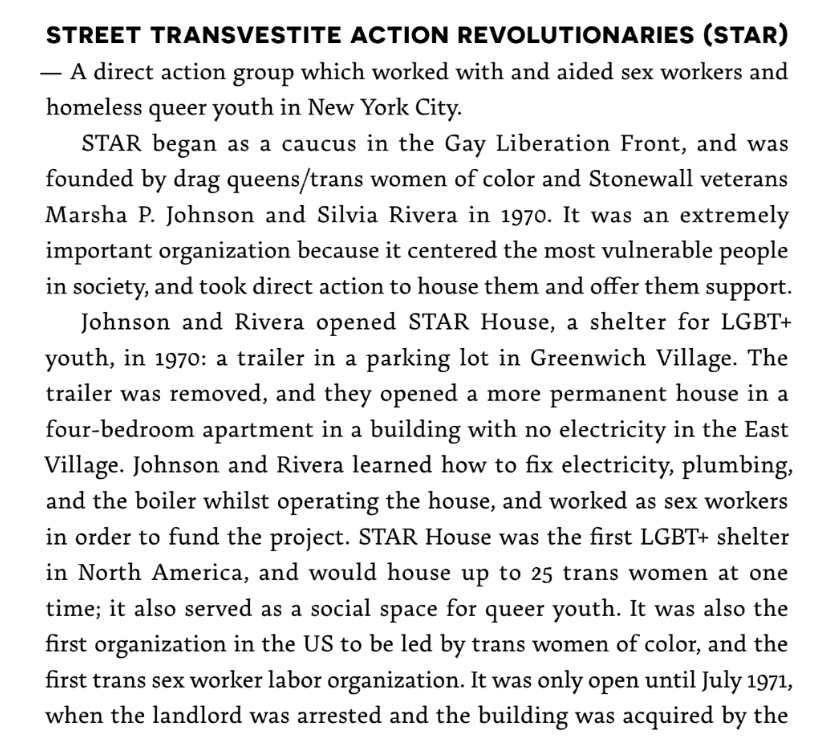

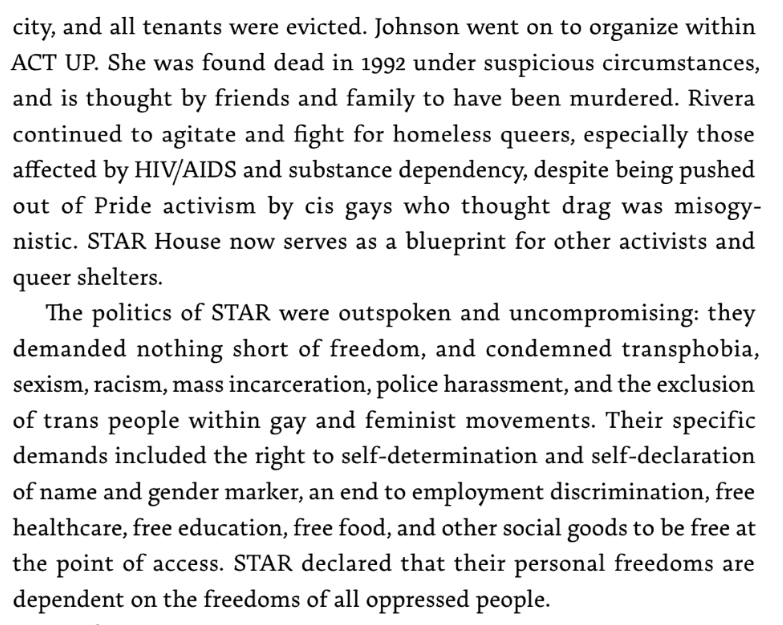

Red Schulte talking about STAR House in the East Village. I remember reading about this recently in an article about Rivera. (Screenshots taken from Morgan Lev Edward Holleb's The A-Z of Gender and Sexuality: From Ace to Ze).

The images are of text that are hopefully accessible with OCR software, but if not or if you do not have access to OCR software, please let me know and I'll make time to transcribe these properly.

Red Schulte notes that the legacy of STAR House is one that is based on providing for one another and caring in the face of systemic violences like criminalisation, in the face of the stigma of #DrugUse, in the face of #whorephobia, which exist and are constantly present.

They note that despite the ideas of cops, the criminal-legal systems, and societally accepted channels because they have no vested interest in listening to sex working people while policing them. So care and support are things these communities have had to build themselves.

They are talking about the 1978 'Take Back the Night' in Boston as a particular historic moment. Sex workers from the Prostitutes Union of Massachusetts got together with the Combahee River Collective. (I think I have read about this and the work with the Boston Bail Project?)

(I'm going to have to come back to this but I'm fairly sure one of the books I was reading recently on the histories of feminist movements had a bunch of stuff about this particular meeting. I'm going to have to go wander through my cupboards again.)

AH! I shouldn't have paused, Red Schulte has got me! It's the Emily Thuma book. That's it exactly. THANK YOU. (This would have taken me days to figure out myself!)

Melissa Grant noting that this is raising the larger issue than one of bringing the police themselves to justice, but of why the police are seen as capable of bringing justice or safety when these communities and their histories have told us all along that it's not the case.

She posits that perhaps these histories are suppressed /because/ they are confrontational with the police, because they are radical, and because of how history itself is constructed. Why were the people in that women's prison not included in these histories? Why leave them out?

She's bringing up one of the points I feel most strongly about: which are questions of who comes into contact with the communities elders who gets to carry these stories; who does the care work; who has access to the possibilities of documenting this; whose voice is heard.

Hugh Ryan notes that a lot of the laws that are now considered traditions of policing were actually originally piloted on sex workers (eg. fingerprinting was piloted on sex workers in NY because it gave them large numbers). He's contextualising this sex work as poverty-driven.

These early arrests were only about women because the legal language used draws distinctions between them and men (using the gender binary), and qualifies prostitution at this early point as to do solely with the "lewdness" of women.

Ryan notes that this meant that all of these women and transmasculine people were thus being policed by this and brought to the women's house of detention. He notes that between this constant policing, forcible geography created by arresting them and confining them to this >

prison, by giving them little to no money in the aftermath of this incarceration, the police inevitably constantly gathered together a community of anyone who was perceived as poor and improperly feminine through these processes, and many of them were likely to be queer.

He posits that, unintentionally (and not without violence), these processes of policing sex work through gender and poverty likely did contribute to creating one of the most known queer spaces in America.

Cecilia Gentili is talking about the links between the criminalisation nexus between gender/ sexuality/ sexual behaviour/ sex work. At the time that she began sex work, by wearing a skirt she could already get arrested. So sex work wouldn't change the fear of arrest.

This also plays out in policing and ideas of power wherein the arrest for sex work becomes about the exertion (and consequent reaffirmation) of masculine power over trans women in particular. The act of policing is not about justice but about power to affirm the masculine self.

Red talking about piecing back together history with whorestory (I am loving this), and linking this to prison newsletters (inside and outside publications) which are physical manifestations of mutual aid: these carry legacies, traditions, strategies, and debates.

Red is talking about No More Cages, the archives of which can be accessed here: https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth-oai:np197v453 (Oh, huh, there's an unexpected overlap happening with my recent reading on queer digital archives and the politics of queer archiving as historical intervention. Love it.)

(This also reminds me that I need to go read that Jeanne Vaccaro piece on crafting and trans histories because it'll likely speak as well to these ideas of physical and material processes of care and legacy in queer communities that I'm getting so much out of in this talk).

Side note: If anyone is interested in reading about crafting and trans histories, I can absolutely put copies into a dropbox or something so more people can get access. Just let me know.

( #CW for brief discussion of #suicide) Also in the back of my brain is this excellent article by Ashley Lucas that talks about community, prisons, survival, queerness, and Shakespeare: https://aboutplacejournal.org/issues/practices-of-hope/tending-together/ashley-e-lucas/

(... I want this book SO MUCH.)

(... I want this book SO MUCH.)

Red noting that there's something powerful about access to material archives, to something that says that there is a legacy that they come from in this struggle. They love the radically inclusive nature of these histories, but also having space to complicate them & get them messy

Melissa noting that access to these sorts of material legacies and spaces isn't present much, and the prison frames that absence, that there's only one sex worker history archive in North America that is dedicated to prison histories. Individual sex worker archives exist though.

Melissa notes that there is a lack of phsyical spaces that memorialise and tell sex worker stories and that these gaps are in some way addressed by prison and jail newsletters being the ways in which those histories, legacies, stories are made present and passed down.

Melissa recounting coming together for the first data and violence against sex workers protest staged in 2003 in front of San Francisco city hall and 6 months later that space is where (briefly) same sex marriages took place, and she notes the distance between these two positions

Reminded SO MUCH of the whole thing right now in India about a push to get same-sex marriages legalised while completely ignoring the Trans Act & all its violences, ignoring the ways in which legalising same-sex marriage does not address stigmatisation, violence, carceral systems

There's a parallel to be made of course with the idea of the "good" homosexual political subject that will then be used to brutally and repeatedly police anyone who does not fit this very specific upper caste, upper/ upper middle class, cis monogamous idea of queerness.

It is also echoing in a lot of ways the ways in which these local struggles for rights are being aggressively sanitised and that when it is historically situated or legacies are provided, complex histories of trans identities, caste identities, sex work, etc are being erased.

There's something about this idea of legacies, of material objects that tell these stories, that's really resonating for me.

Side note but I've had a recent chance to start listening to/ reading some of the histories of the queer collective I'm part of, and these aren't public.

Side note but I've had a recent chance to start listening to/ reading some of the histories of the queer collective I'm part of, and these aren't public.

I think this is why Melissa's questions are resonating so strongly for me: the fact that if I wasn't present here in this moment, if this was something I put off to later, would I still have access to these stories or these histories? Would I have these material records to hold?

And of course there are larger questions of how these documents would function in a public sphere, even if they were to become public, because many of the things I find dearest are the most ridiculous things, but I don't know how those would function outside of these intimacies.

(Welcome to Samira read an article about intimacies, politics, and queer archiving a week ago and has had non-stop feelings about it pretty much since then.)

I think there's also a really interesting question that I'm wrestling with because queer histories and histories of sex work overlap, but not everyone in these spaces has access to that overlap based on their own politics or choices, and that's a complicated negotiation too.

What happens to these complicated and complex histories when you come in and you want to claim some but not all because of the different spaces you occupy and the ways you have come to these spaces? What happens then? (I think Red gets at this when they say it gets messy).

Back to the talk. Melissa notes that violences are dual in this: trans people are being told that they will not survive and they are not documented and memorialised in the same way, and at the same time there is a complete lack of commitment to keeping them alive as well.

Oh interesting! Melissa pointing out that while sex work movements and queer movements can overlap or be distinct, the current mainstreaming of the sex worker movement has happened alongside of the mainstream visibility of trans rights.

She notes that the hypervisibility of trans sex workers, particularly those from Black and migrant communities, are the ones most harmed but are also the ones carrying the day and out there fighting. Their work makes these politics deliberately present, visible, essential.

Cecilia noting that she felt often that while she could be present in movements, she didn't necessarily feel she had the sort of learning or academic background to be part of organising. She's pointing to the way in which organising power itself ends up tied to institutions.

This is such a major point. There's a real problems with how activist movements themselves end up forcibly gentrified and this is often also produced through structures of in-communities and out-communities within these communities themselves. It's something to constantly refuse.

I love that Cecilia notes that claiming that space in activism has changed her life dramatically. It's so important, and it pushes back on the ideas that exclude trans women from these movements.

Hugh Ryan keeps coming back to the idea of who owns and who makes space, particularly these ideas of who has access to space at all. This is reminding me a lot of work that queer collectives have done out here on the ways in which public spaces like parks, etc are policed now.

Despite the fact that these parks are government parks and for the public, sex workers, local trans communities, poor people, homeless people, people who use drugs, etc, are all being excluded from these spaces despite very much being part of the "public" entitled to them.

It's not only a deliberate gentrifying, it puts these communities at risk as they do not have community or collective space. (There is a lot of research on this that was presented at TISS Mumbai a few years ago. I'm blanking on the researcher names but I hope they publish.)

AHA! I went and dug out my old notebook for 2018 and found notes I took while at the exhibition. The researchers are Sunil Mohan, Rumi Harish, and Radhika Raj. The project was on the gentrification of Bangalore parks and who gets created as the idealised "public" by the state.

(Honestly, my spiderweb of a memory is why I need notebooks for everything. I am a terrible academic for many reasons but my shockingly bad memory is definitely one of them.)

In these "public" parks (often corporate sponsored), these researchers noted that it wasn't even that local communities who used those spaces for care who were excluded through gentrification, but that anyone perceived as "lesser" could not access things like park toilets, etc.

So this affected not only homeless people, poor people, trans communities, sex workers, etc, but also gardeners, security workers, cleaners, etc (often noted with caste and class lines) who weren't seen as "acceptable" to use these gentrified upper caste upper middle class spaces

Hugh Ryan is noting that these communities, queer communities made up of women and transmasculine people, created culture on the street. He traces this back as far as 1939 with Walter Winchell the gossip columnist saying that the House of Detention makes the Village queer.

He notes that these people are still being pushed out of these spaces, they are still being forced away, and the implication is that the neighbourhood belongs to the gentrified gay community there, and he wants to push back on that because it is not true and is active erasure.

Red links this to Alicia Walker and a discussion about public moments of celebration such as International Whore's Day (2nd June, named for this event: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occupation_of_Saint-Nizier_church_by_Lyon_prostitutes) and pride, and noting that she needs these to feel connected to her communities who fight/ resist.

This discussion is reminding me of Alice Birch's play [BLANK] that I went to see last year while in London. I think it's a play that doesn't sanitise people and make them simple in order to show you that prison is wrong. It leaves them messy and broken, and prison is still wrong.

If you're looking for a review, read this one. Trust not the guardian's review; I'm sorry but that dude is crap. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/theatre-dance/reviews/blank-donmar-warehouse-play-review-alice-birch-clean-break-anniversary-jemima-rooper-a9164606.html

I will say that I thought the play was uneven, but I think that was actually good for me. I don't know that I could have trusted it if it wasn't? It is not an easy watch by any means and the script gives you less distance, so ymmv: https://www.amazon.com/BLANK-Oberon-Modern-Plays/dp/1786829487

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter