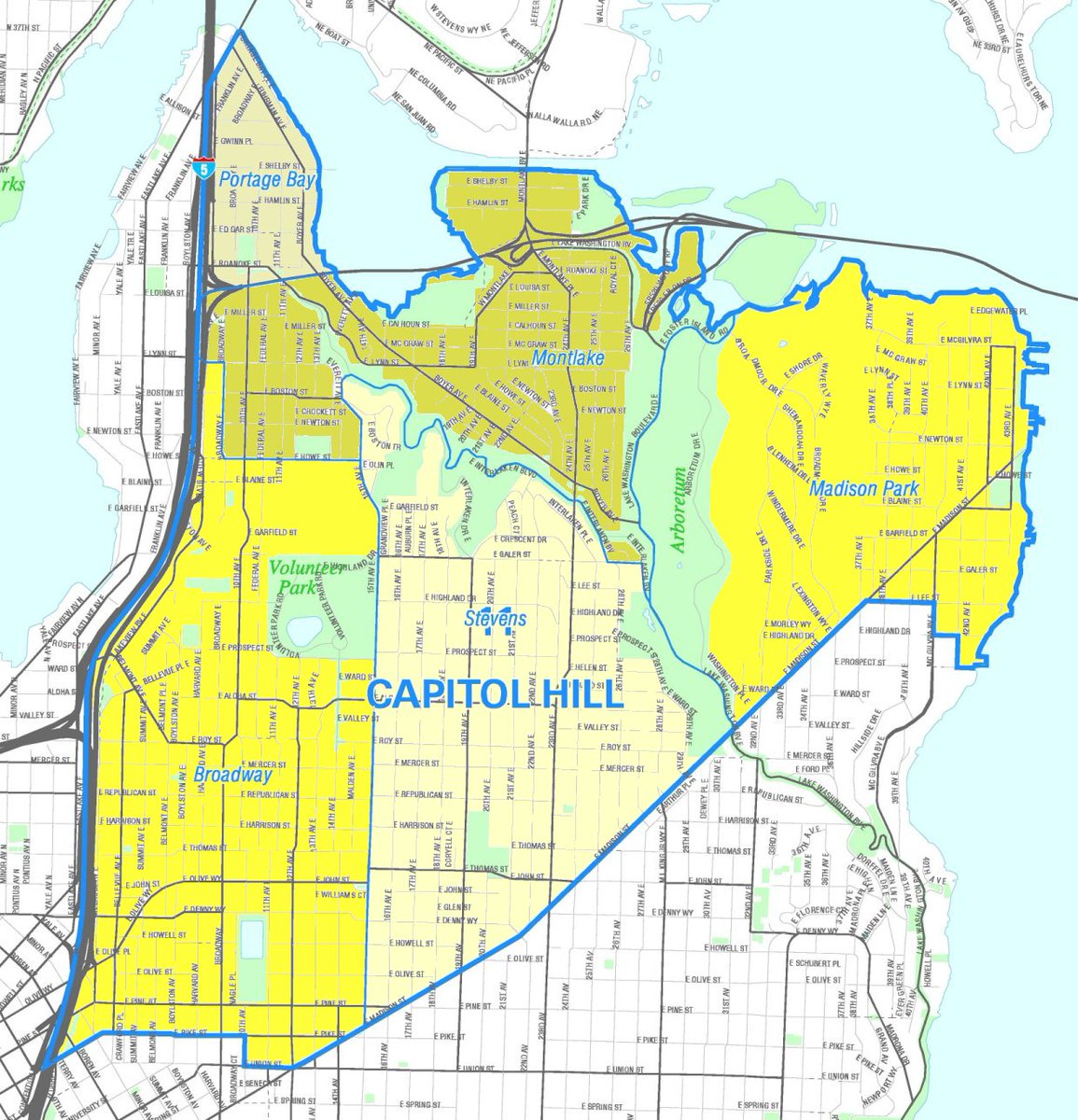

Capitol Hill Organized Protest (CHOP), a local symbol of the movement for black lives, sits on the southern edge of a huge section that was formerly reserved for whites only.

(2/19)

(2/19)

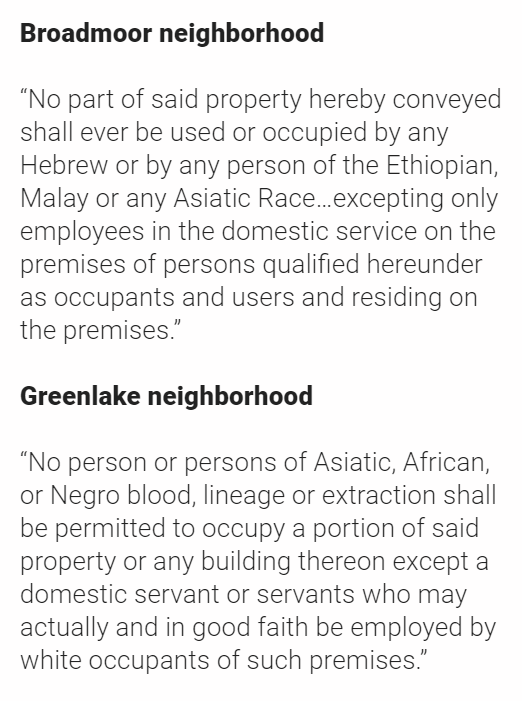

This was enforced through restrictive covenants written into the deeds that prevented black people and other races from holding or occupying land. University of Washington provides samples of the language used in various neighborhood documents:

(3/19)

(3/19)

These were a way to get around a 1917 Supreme Court case that ruled city-wide segregation ordinances unconstitutional. The 1926 Corrigan v. Buckley upheld their legality, arguing that private developers and homeowners were exempt.

(4/19)

(4/19)

In the Twenties, like many other northern cities, Seattle saw an influx of black residents during the Great Migration from, prompting organized efforts by whites to keep black tenants and homeowners out.

(5/19)

(5/19)

A year after Corrigan v. Buckley there was a campaign by members of the Capitol Hill Community Club to persuade residents to agree not to sell or rent to “Negroes, or any person or persons of the Negro blood.”

(6/19)

(6/19)

By the end of the three-year campaign, the restrictions covered a total of 964 home owners, 183 blocks, and 958 lots, according to a 1947 report by UW student Katherine Pankey. They would be in effect for 21 years.

(7/19)

(7/19)

The Housing Act of 1934 created the practice of “red-lining” which identified certain neighborhoods—most often black ones—as risky for investment. This further incentivized the use of racial covenants by by white neighborhoods hoping to avoid being red-lined.

(8/19)

(8/19)

In the 1940s, as the covenants were set to expire, the CHCC launched a campaign to encourage homeowners to renew them, arguing they were needed for the “mutual benefits, protection, preservation and promotion of the value of that land and properties”

(9/19)

(9/19)

The CHCC was resisted by the Civic Unity Committee, a coalition of civil rights groups including the NAACP and the Christian Friends of Racial Equality, a multiracial church-based organization comprising and led by women.

(10/19)

(10/19)

The CUC engaged in a highly successful letter-writing and education campaign to convince homeowners not to renew the covenants. Not a single one was extended when they expired in 1948.

(11/19)

(11/19)

That same year, in Shelley v. Kraemer, the Supreme Court ruled restrictive covenants legally unenforceable. Of course, this wasn’t the end of housing discrimination.

(12/19)

(12/19)

No longer able to enforce covenants legally, white communities turned to threats of violence and other forms of intimidation to keep non-whites out.

(13/19)

(13/19)

In 1952, Austrian Holocaust refugee Richard Ornstein bought a home in the Sand Point Country Club area. The realtor who sold it to him was unaware that the deed included a restrictive covenant.

(14/19)

(14/19)

Daniel Allison, head of the neighborhood association, told the realtor the community will not have Jews as residents” and warned of ways that Ornstein’s prospective neighbors might respond.

(15/19)

(15/19)

According to the ADL, “Allison also warned that if the Ornsteins moved in, their child ‘could’ be made uncomfortable, their driveway ‘could’ be blocked off, and the streets and their utilities ‘could’ be cut off.”

(16/19)

(16/19)

In addition to social coercion, bank loan discrimination also continued to maintain segregation. These practices were outlawed by civil rights legislation in the 1960s.

(17/19)

(17/19)

However, the legacy a racial covenants can still be seen today in Seattle and elsewhere as de facto segregation takes the place of de jure. Non-whites continue to be priced out of areas and discriminated against despite legislation.

(18/19)

(18/19)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter