So yesterday I introduced all of you to my dissertation research.

I ended on a cliffhanger with a promise to continue today, so here we go!

(Here's yesterday's thread: https://twitter.com/cwjones89/status/1275412504219435008?s=20)

I ended on a cliffhanger with a promise to continue today, so here we go!

(Here's yesterday's thread: https://twitter.com/cwjones89/status/1275412504219435008?s=20)

To start off today, we need to go back in time. My dissertation covers the years 745-612 BC, but in order to understand it we need to look at the period before this, from 826-745 BC.

Ancient historians sometimes call this period “the Crisis of the Eighth Century.”

Ancient historians sometimes call this period “the Crisis of the Eighth Century.”

We have very few sources, so it’s not clear what happened and it’s hotly debated. But what is clear is that high officials were wielding power and prestige in ways they had not before.

The Assyrians kept track of time by naming years after officials. This was an honor as it meant everyone who took out a loan or sold land that year (anything you would get notarized today) would date their transaction by your name. You’re famous!

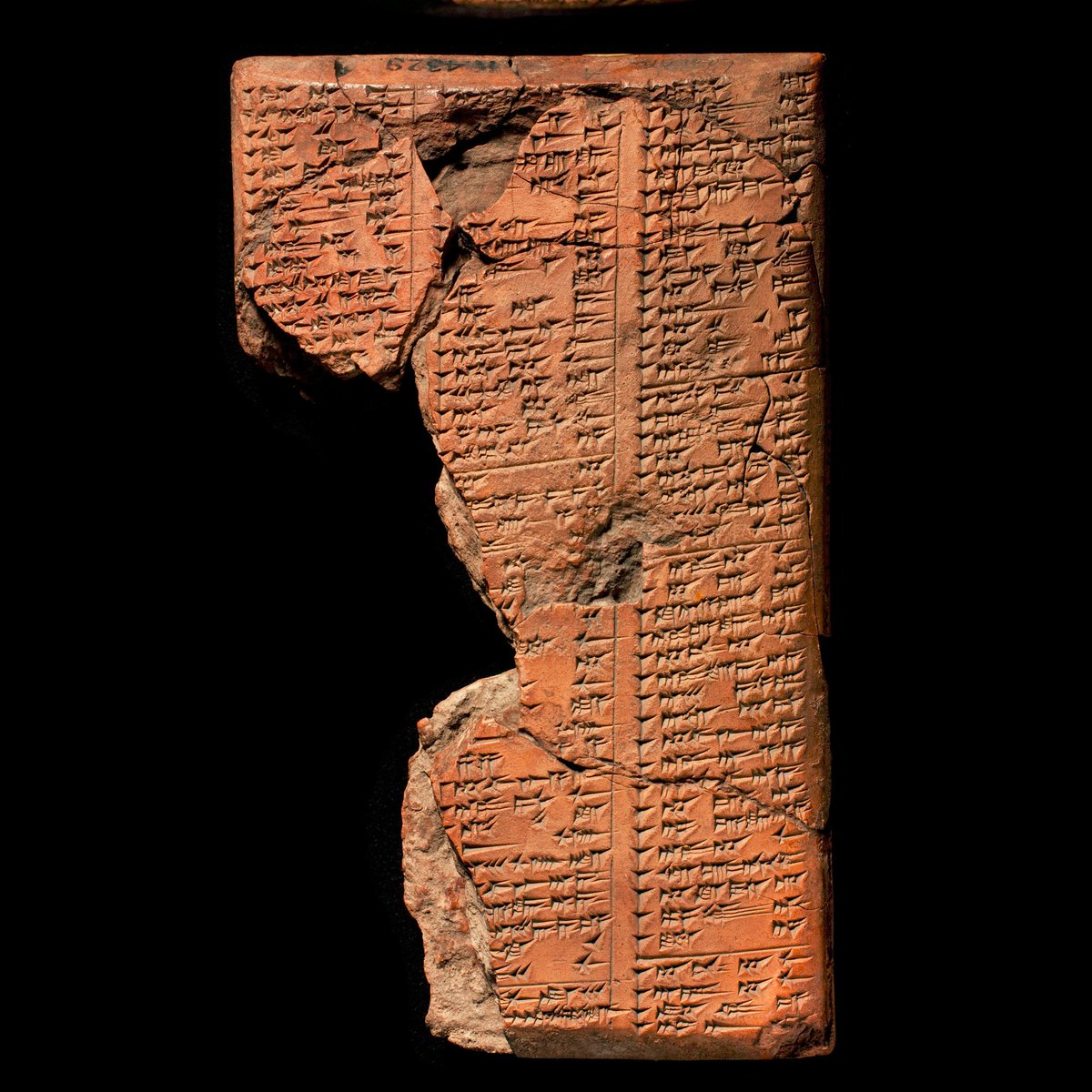

They had to keep lists of all the year-names (called “limmu”) so they could remember the right order. The good news is archaeologists have found enough tablets to compile a complete list for the years 910-649.

(Before and after that, things get confusing.)

(Before and after that, things get confusing.)

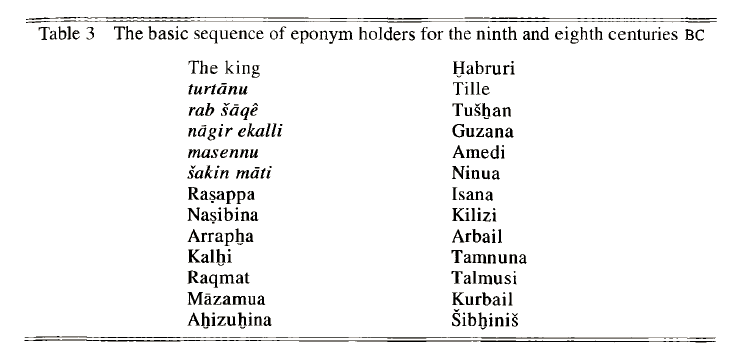

The limmu-lists show that limmus were actually assigned in a specific order:

First the king, in the first year of his reign.

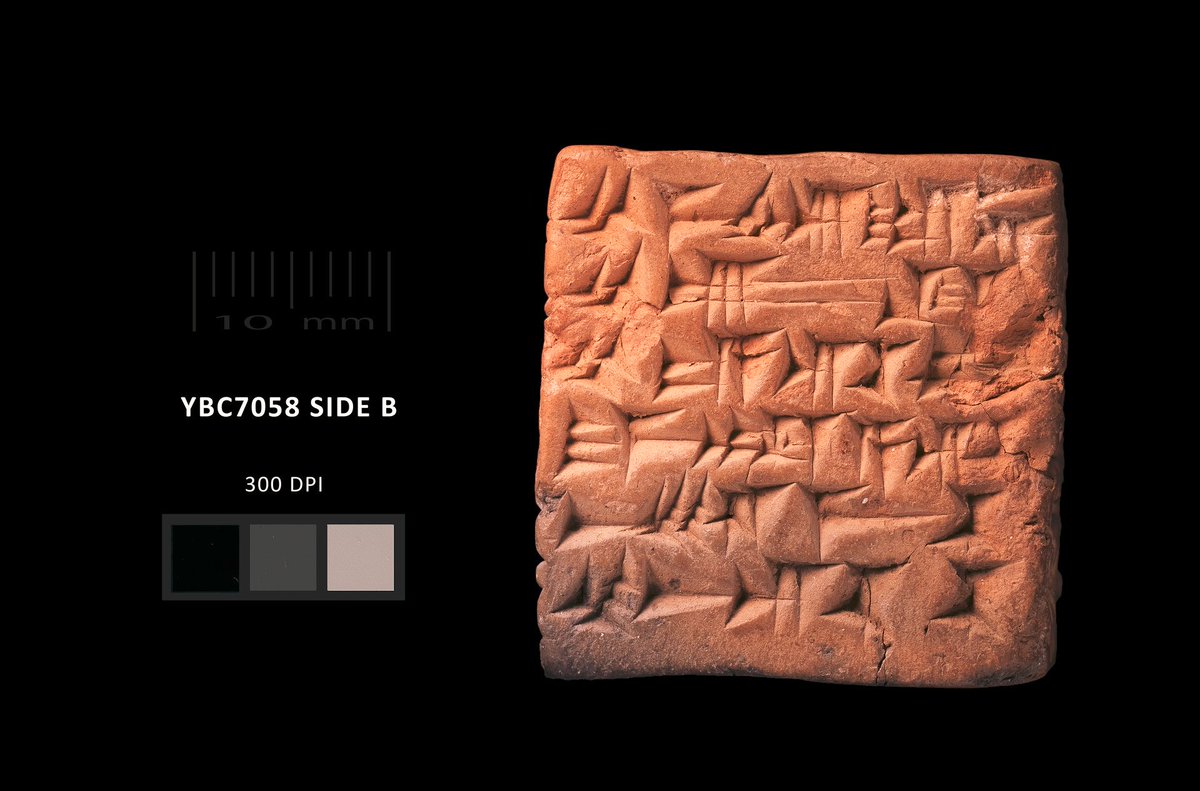

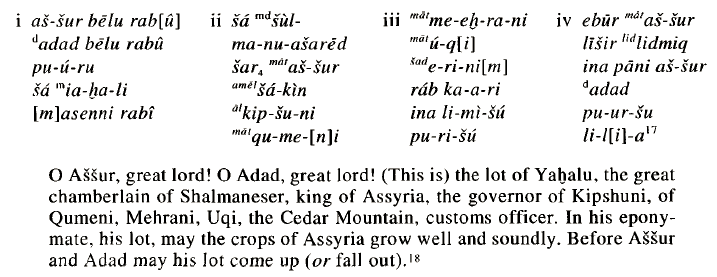

Then four of the leading officials in the kingdom. They drew names for the exact order, using inscribed cubes like the one below:

First the king, in the first year of his reign.

Then four of the leading officials in the kingdom. They drew names for the exact order, using inscribed cubes like the one below:

Then came provincial governors in a set order, beginning with the governor of Ashur, Assyria’s ancient capital and the home of its chief god and then other governors of provinces in a set order by province.

(From Millard, Eponyms of the Assyrian Empire, p. 8-11)

(From Millard, Eponyms of the Assyrian Empire, p. 8-11)

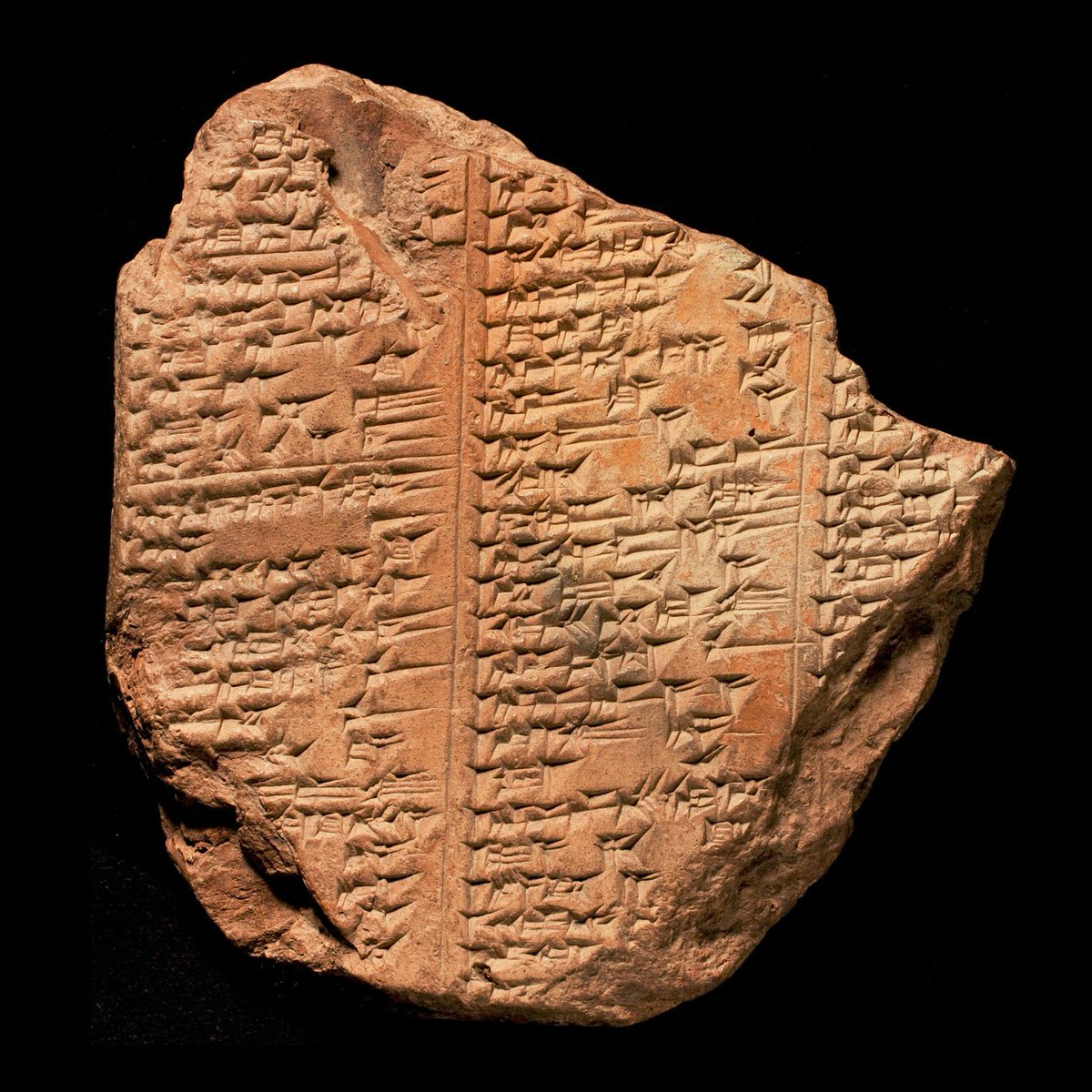

OK, so back to the Crisis of the Eighth Century. The really high ranking officials, those first in line to be limmus, are doing things that usually only kings did.

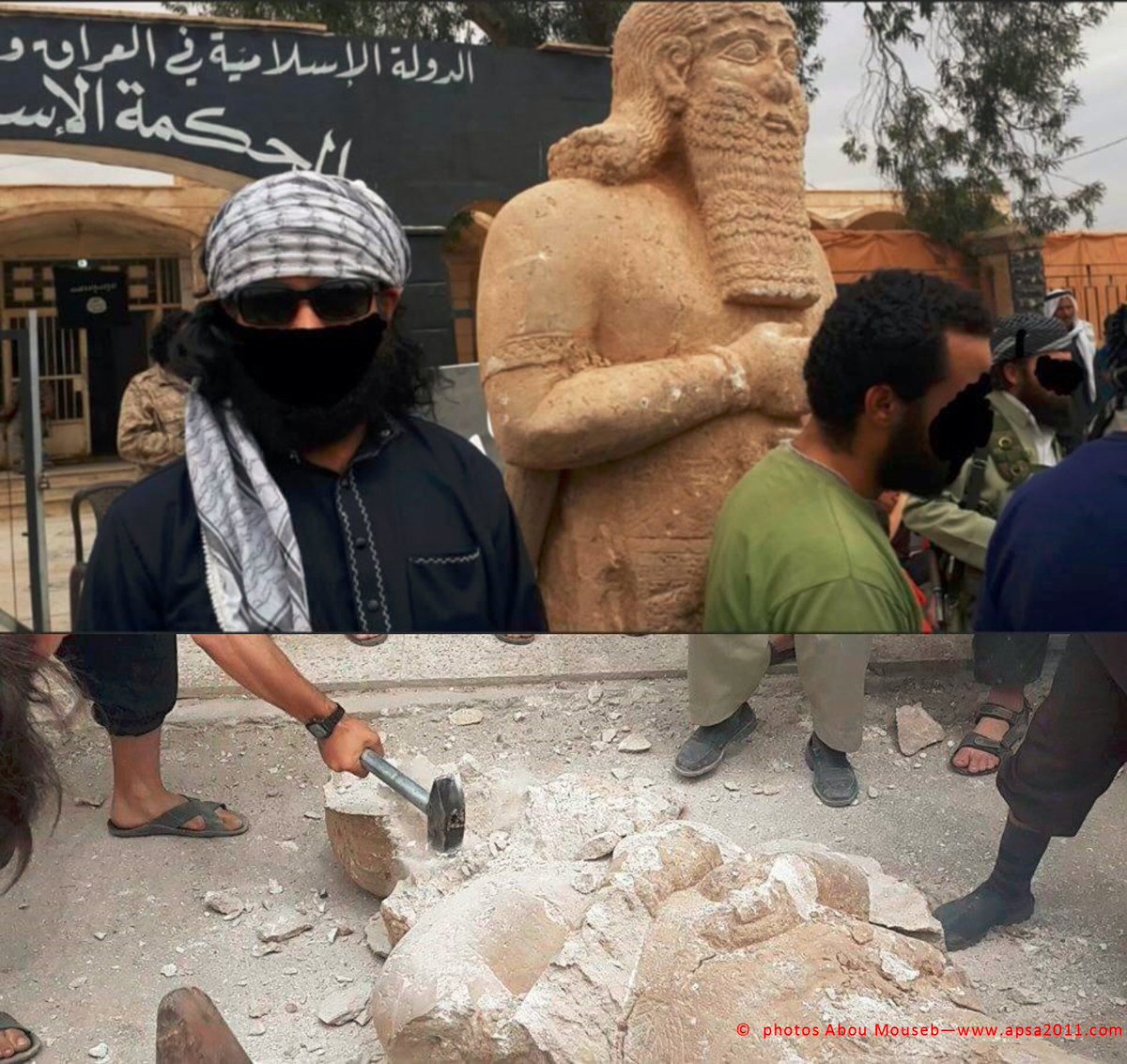

Like setting up monuments along the borders of the empire showing themselves on the same level as the king:

Like setting up monuments along the borders of the empire showing themselves on the same level as the king:

High officials set up monuments like Assyrian kings used to, except not quite claiming to be kings themselves, just stating that they led armies and built things and cared for the people.

Some of these were found by ISIS in 2015 and smashed.

Some of these were found by ISIS in 2015 and smashed.

The Assyrian Eponym Chronicle, a document which lists limmus alongside important things that happened that year, lists 13 years where revolts took place, plus two with plagues.

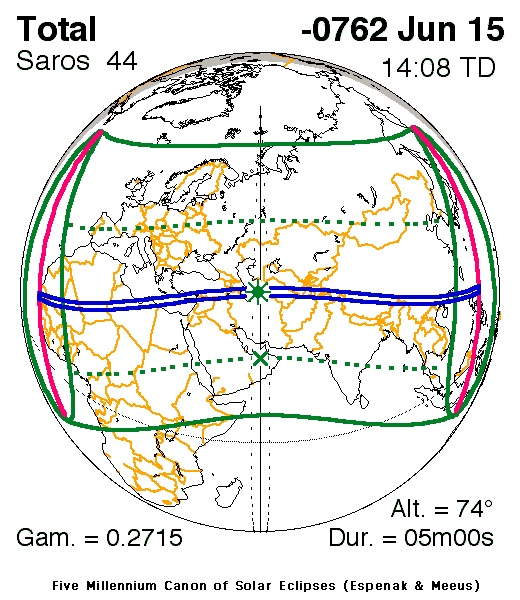

(For 763 it also mentions a solar eclipse, which is how we can convert these dates to our calendar)

(For 763 it also mentions a solar eclipse, which is how we can convert these dates to our calendar)

Clearly things were in a general status of “not great” and governors seem to have been doing their own thing much of the time. Were governors responsible for some of these revolts? Probably. But in most cases they remained loyal to the king.

It’s just that the potential for telling the king to go jump off a cliff was always there. And when Tiglath-Pileser III seized power in a revolt in 745, he found this unacceptable.

He and his son Sargon II carried out far-reaching reforms to blunt the power of the aristocrats.

He and his son Sargon II carried out far-reaching reforms to blunt the power of the aristocrats.

First, they expanded the number of provinces. Each governor now controlled a smaller piece of the pie.

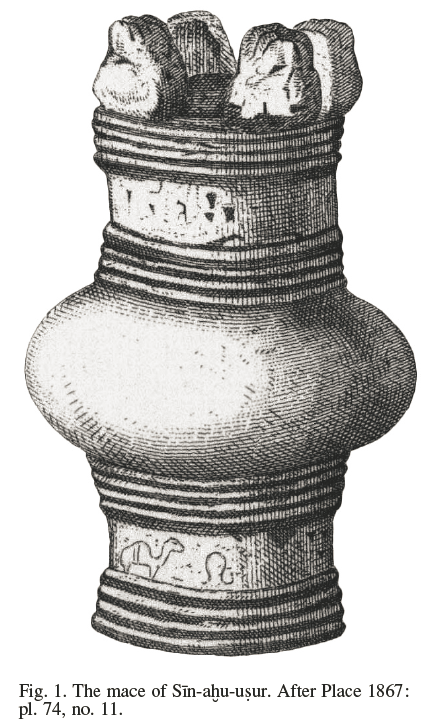

Second, new offices were created. Sargon II revived an old office called the sukkallu which had not been used in 500 years. And then appointed his brother Sin-ahu-uṣur to it.

Second, new offices were created. Sargon II revived an old office called the sukkallu which had not been used in 500 years. And then appointed his brother Sin-ahu-uṣur to it.

Third, SNA data shows that the people Sargon II appointed to limmu-offices were not well connected. In other words, he’s picking people without a wide network of supporters.

Guess who doesn’t get to be a limmu? Actually powerful people, like his brother Sin-ahu-uṣur.

Guess who doesn’t get to be a limmu? Actually powerful people, like his brother Sin-ahu-uṣur.

Sargon II is killed in battle in 705. His son Sennacherib junks all precedent and just appoints whoever he wants as limmu. There is no set order and there’s no point in waiting your turn. It goes to whoever the king wants to put there.

Creating more officials and keeping them fighting for smaller pieces of the pie helps keep the king on top.

It’s easier to keep everyone in line and prevent a repeat of the Crisis of the Eighth Century when they’re fighting each other.

It’s easier to keep everyone in line and prevent a repeat of the Crisis of the Eighth Century when they’re fighting each other.

But this had unintended consequences.

We can see this in the networks.

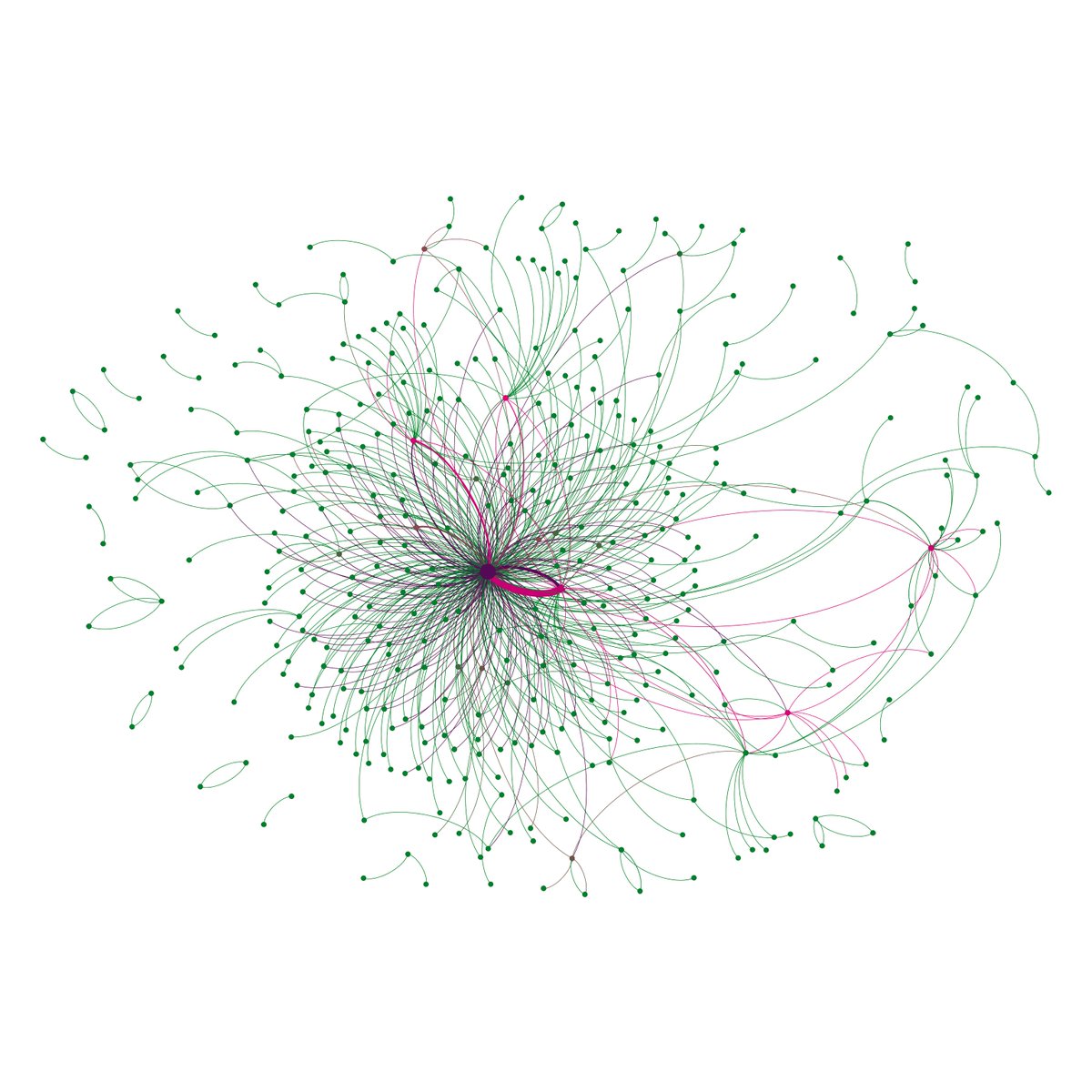

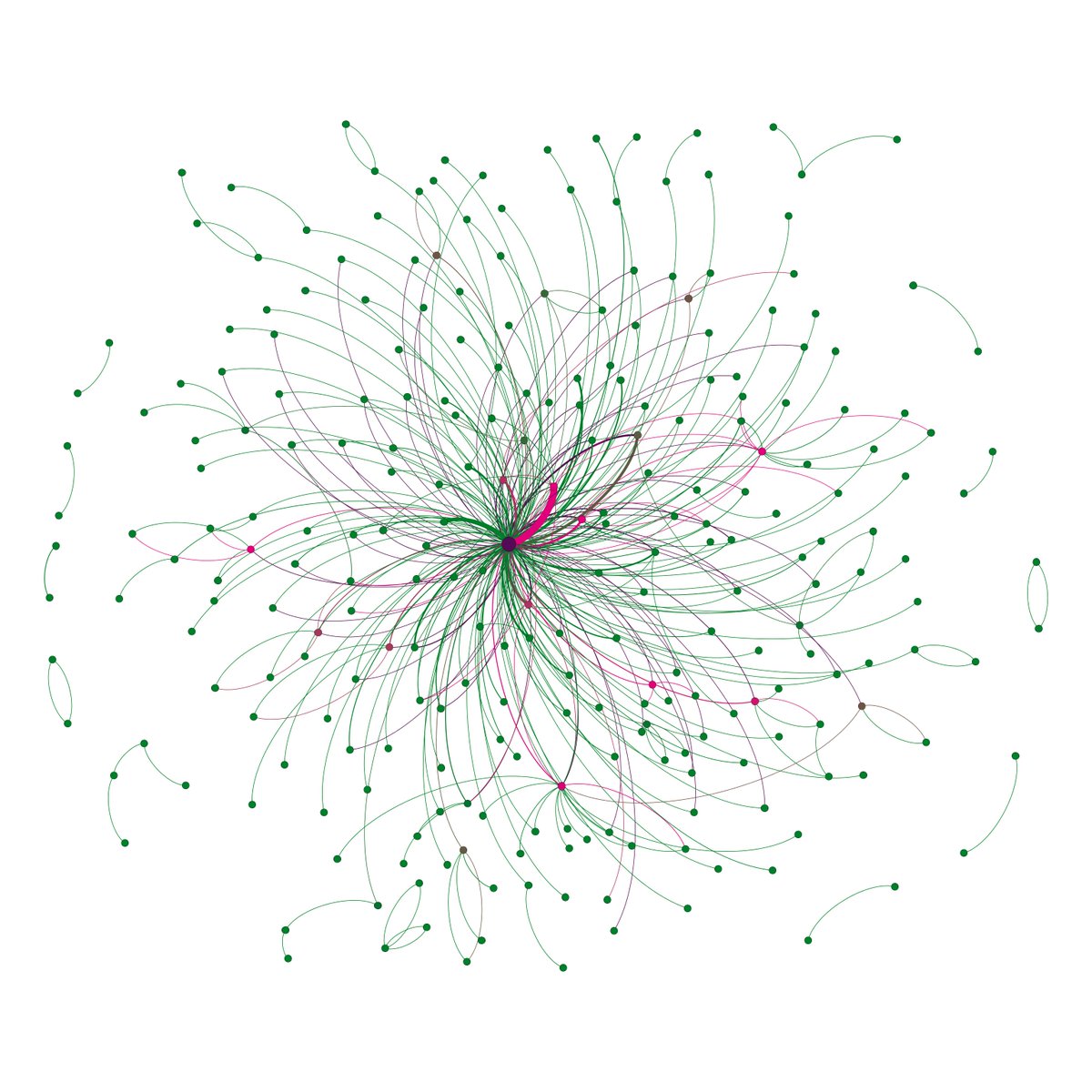

Network on the left is Sargon II (r. 722-705). Right is Esarhaddon (r. 681-669).

We can see this in the networks.

Network on the left is Sargon II (r. 722-705). Right is Esarhaddon (r. 681-669).

There is a measure called ‘network diameter’ which measures the maximum # of jumps it takes to get from one side of a network to the other.

It drops from 7 to 5.

People are less open in communicating information they hear from other people.

It drops from 7 to 5.

People are less open in communicating information they hear from other people.

Esarhaddon’s father Sennacherib had been murdered by his own sons whom he passed over in the line of succession. Under Esarhaddon there was an environment of paranoia.

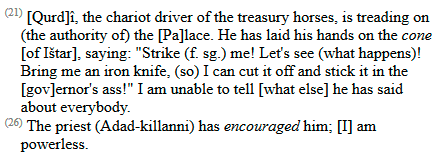

Anonymous denunciations were common. Here’s one from the city of Guzana (Source: http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/P313461/html)

Anonymous denunciations were common. Here’s one from the city of Guzana (Source: http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/P313461/html)

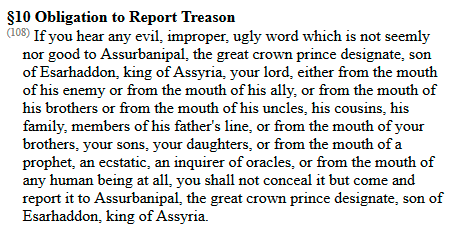

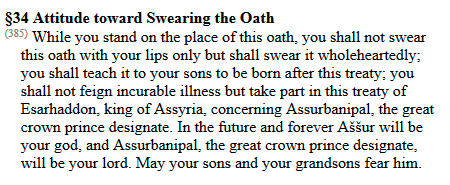

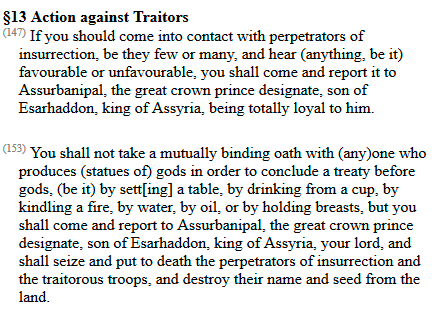

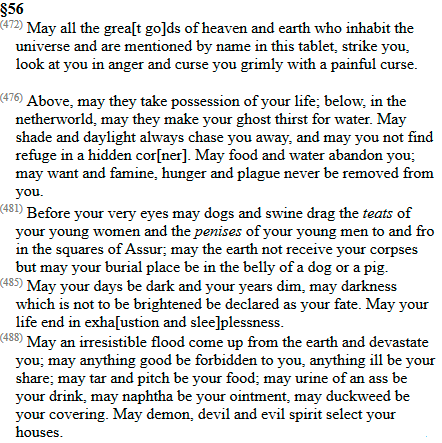

When Esarhaddon chose a successor in 672 he made every official in the empire swear a lengthy oath to defend his choice. He put copies in the temples in their headquarters to remind them who they swore by.

Here are some excerpts. Read the whole thing here http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/Q009186/html

Here are some excerpts. Read the whole thing here http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/Q009186/html

Then there’s this laconic line from a Babylonian historical chronicle about the events of 670 BC:

“The eleventh year: In Assyria the king executed many of his leading officials.”

“The eleventh year: In Assyria the king executed many of his leading officials.”

What does this mean? An environment built around paranoia, where everyone is trying to screw each other over while avoiding ending up dead themselves, means the king gets worse and worse information.

This creates even more opportunities to do away with someone you don’t like.

This creates even more opportunities to do away with someone you don’t like.

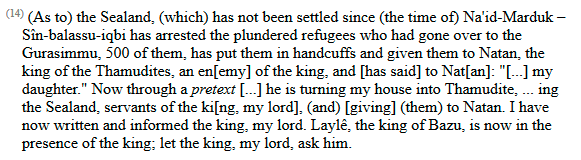

We see an example of this in the following letter sent by Nabû-bel-šumate, the governor of the Sealand (the marshy region of southern Iraq where the Tigris and Euphrates meet the Persian Gulf) to the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (r. 669-631).

In this letter he denounces Sin-balassu-iqbi the governor of Ur, accusing him of slave trading and plotting to make a marriage alliance with a hostile Arab sheikh. He insinuates that Sin-balassu-iqbi is disloyal.

(You can read the letter here: http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/P452649/html)

(You can read the letter here: http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/P452649/html)

He wasn't the only one - others also accused Sin-balassu-iqbi of double-dealing, and he was replaced by one of his brothers.

But when civil war split the empire in 652, Nabû-bel-šumate joined the rebels and fought a four year guerrilla war against Assyria.

But when civil war split the empire in 652, Nabû-bel-šumate joined the rebels and fought a four year guerrilla war against Assyria.

He eventually fled to Elam (in modern Iran). Demands for his extradition led to an Assyrian invasion and the destruction of the Elamite capital of Susa and other major cities in 646 (like Hamanu shown below).

The Elamites then agreed to hand him over. He killed himself first.

The Elamites then agreed to hand him over. He killed himself first.

The Elamite king sent his body to Assyria packed in salt, to prove that he was dead.

Ashurbanipal claimed that after he received the body “I made him more dead than before.”

He cut off his head and made another rebel wear it as a necklace.

Ashurbanipal claimed that after he received the body “I made him more dead than before.”

He cut off his head and made another rebel wear it as a necklace.

This is just one example, and somewhat exceptional. But it illustrates well the kinds of things that could happen when officials denounced each other, and that very likely no one’s hands were actually clean.

Neo-Assyrian officialdom was a tank full of piranhas.

And this piranha tank was created by the system set up by Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II in a bid to re-assert royal power in the late 8th century.

And this piranha tank was created by the system set up by Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II in a bid to re-assert royal power in the late 8th century.

This brings me to my final point:

We have been blinded by the abundance of sources and the artistic achievements of the last 132 years of the empire.

We think of Assyria from 745-612 as Augustan Rome, rising to new heights.

We have been blinded by the abundance of sources and the artistic achievements of the last 132 years of the empire.

We think of Assyria from 745-612 as Augustan Rome, rising to new heights.

Instead, I would suggest that Assyria from 745-612 was closer to Rome from 284-410 AD. Still powerful and feared on the outside but riddled with internal structural weakness, wealth inequality, and overly centralized power on the inside.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter