In our own tasks, when we find low scores, we usually discover it’s due to lack of clarity by experimenters (or translators), not evidence of inability. We address this by having controls to ensure participants understood the task. But IQ tasks don’t have a control condition.

Nobody who knows the Tsimane’ would think they are intellectually handicapped--they have, for instance, extensive ethnobotanical knowledge that would surpass most US adults. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/299/5613/1707

But ethnobotanical knowledge, or thinking about causal relations in natural kinds, or training dogs to hunt, or surviving alone in the rain forest aren't tested in IQ tests. What is tested instead in "culture fair" IQ tests are visual relations, geometric shapes, patterns, etc

But cultures differ in, for example, whether they have words for shapes, spatial relations, etc. These differences influence how people think about and use categories @glupyan ( http://sapir.psych.wisc.edu/papers/lupyan_2012_languageAugmentedThought.pdf )

We've found that many Tsimane’, for instance, don't know shape labels. Then why should anyone *ever* run tests that could be influenced by knowledge of shapes with the Tsimane’?

(It’s actually not clear that people without printed materials understand pictures in the same way we do. Here's Tepilit Ole Saitoti, from his autobiography, The Worlds of a Maasai Warrior)

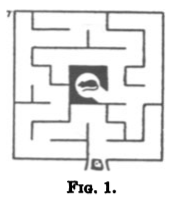

For a “culture free” IQ test, Cattell even suggested that people could be given mazes. I wonder if he thought about the fact that some indigenous people have never been in a hallway.

The only way to sum this up is that the term "culture fair" is just a total fabrication.

Thinking about large cultural differences between people who live far away and speak different languages (non-WEIRD-vs-WEIRD) should motivate us to think about potential cultural and experience-based differences between people who speak the same language and live nearby.

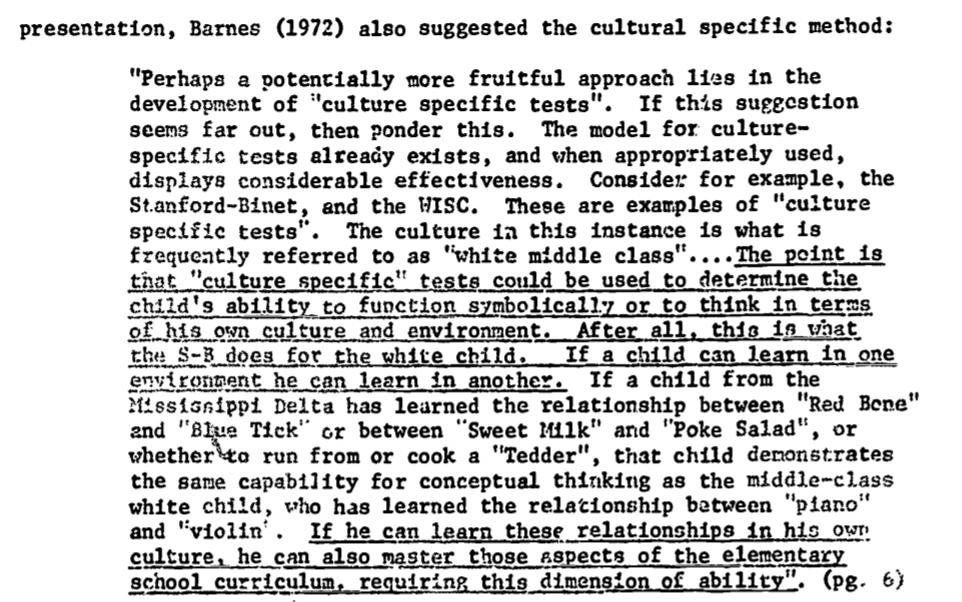

Such differences were highlighted decades ago with examples that show the cultural baggage inherent in creating any test. If you construct the right IQ test, as in "The Black Intelligence Test of Cultural Homogeneity", black children score higher than white children.

(Another example is the "Dove Counterbalance General Intelligence Test", though it's rightly condemned for racist stereotypes http://baltimoretimes-online.com/news/2013/oct/18/chitling-test-controversy/)

And bias in psychology is not just in IQ testing. https://mobile.twitter.com/duane_g_watson/status/1274475980724338689

Besides the unavoidable culture-ladenness of completing a written exam, there are other good reasons to doubt IQ tests meaningfully measure ability.

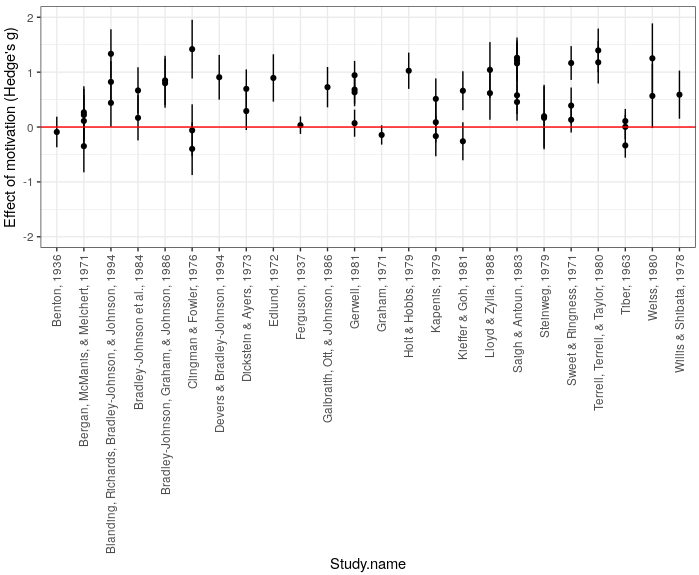

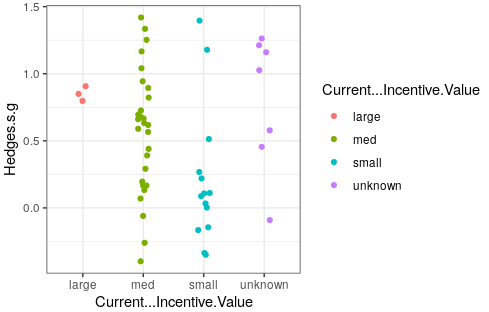

One big one is that performance on them is sensitive to factors that nobody would consider "ability." For instance, if you pay people more, they will do better. The size of the effect across studies averages to about 0.5 SD @angeladuckw https://www.pnas.org/content/108/19/7716

(Note that this meta-analysis included some apparently fraudulent data (Breuning) but the result still holds once it's removed)

Moreover, as motivation would predict, the effect of reward in IQ test performance appears sensitive to the size of reward.

So, IQ tests in part measure how much effort you're willing to exert, not ability. What's worse, we don't know how large an effect motivation *could* have w/ optimal intervention because the field has not considered it important to figure out the dose-response curve.

Demonstration of effects of extrinsic motivation need to make us worry about individual variation. The problem is that individuals and groups almost certainly vary in motivation--people in extreme situations or poverty or other countries may not care much about doing your test.

A second example can be found in large effects of coaching and practice, which has effect sizes up to 0.15-0.43 SDs (again, no determination of how large the effect could be made to be).

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1984-16352-001

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1984-16352-001

Even if most people aren’t explicitly coached, any effect is troubling because it makes you wonder what other activities *could* effectively function like coaching (e.g. individual variation in parental talk about general academic or test or metacognitive strategies, etc.)

Overall, these findings reflect a primary failing of IQ research: it *equates* ability with outcome on a standardized test. This assumption is so ingrained in research assumptions, it’s rarely questioned.

But in other areas of psychology, this assumption is common enough it has a name: “the fundamental attribution error”---presupposing behavior (test performance) is driven by internal ("ability") rather than external factors.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamental_attribution_error

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamental_attribution_error

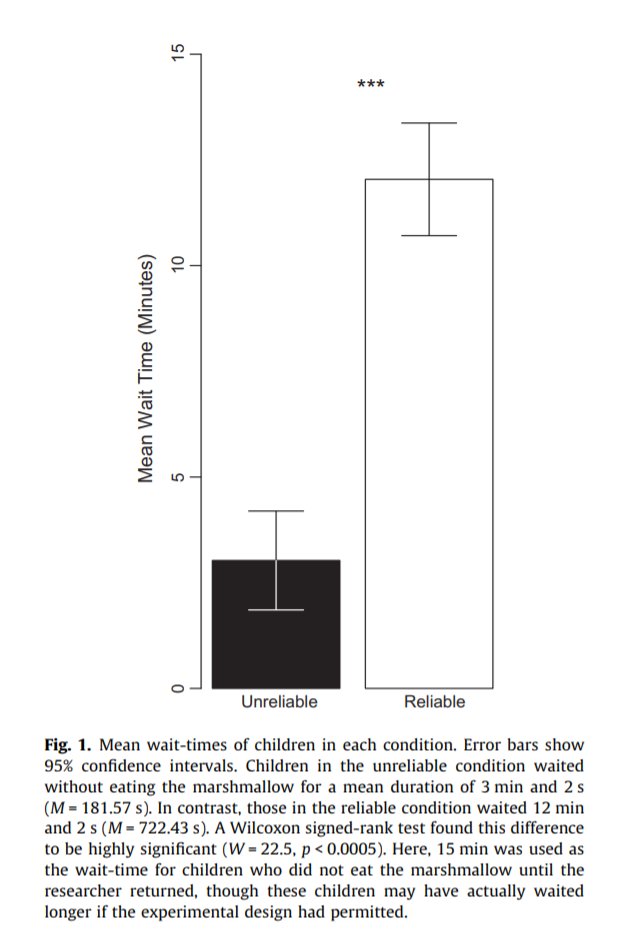

A study that illustrates this perfectly in a nearby domain is the marshmallow task. Early studies by Walter Mischel reported correlations between the ability to delay gratification and life outcomes.

But @celestekidd (et al.) realized that these studies were confounded by environmental reliability: for instance, maybe poor kids *should not* delay gratification because, based on their experiences, promised rewards are less likely to materialize.

As with motivation, a way to test this is to manipulate reliability in the lab. When do you do that, you find the manipulation completely drives whether kids wait.

http://celestekidd.com/papers/KiddPalmeriAslinCognition2013.pdf

http://celestekidd.com/papers/KiddPalmeriAslinCognition2013.pdf

It’s not that kids *can’t* wait. It’s not “ability.” It's a rational judgement about a reward's expected value. And the effect is huge---ceiling and floor. (It was recently replicated by an independent lab: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022096519303662)

Many arguments made about IQ were also made to support the marshmallow task--it correlates with real world outcomes, it's stable over time, varies reliably across cultures and demographics, etc.

These arguments all turn out to be confounded because nobody considered how external third variables--in that case, situation reliability--might affect performance on the underlying task itself, and be correlated with those other outcomes.

That points to a big problem for you too, IQ.

The wrongheaded jump to internal causes should be a real lesson. A measure can be replicable, consistent over a lifespan, correlated to life outcomes… and not at all capture what you think it does.

Note that this isn’t a debate about g or positive manifold. It’s not a question about nature vs nurture. It’s a question about whether the underlying data that go into these studies measure an “ability” or something else.

I’m also not claiming there is no variation in intellectual capacity between people. The claim is that you don’t know what drives variation in performance. Tests haven’t been controlled for countless unmeasured, “non-ability” factors that might influence test scores.

Motivation? Not measured. Expectations? Not measured. Test familiarity? Not measured. Interest in the task? Not measured. Attention? Not measured. Confidence? Not measured. Wandering thoughts about financial insecurity? Not measured.

Stress at home? Not measured. Hunger because you couldn't buy breakfast? Not measured. How much do you care about making the experimenter or teacher happy? Not measured. Rapport with your teachers or experimenters? Not measured.

Linguistic confidence in the test language? Not measured. Native dialect? Not measured. Belief you'll get the promised incentive? Not measured. Knowledge of test taking strategies? Not measured. Confidence you understood instructions? Not measured.

What do you know or believe about your own intelligence? Not measured. Do you like or hate puzzles or puzzle games? Not measured. What did parents say or do to ensure kids cooperate in the test or experiment? Not measured.

How easily do you understand what experimenters want? Not measured. How much do you like doing what others want? Not measured. ( @cantlonlab told me about a kid in an IQ test who said "mouth" when asked to name a container for cereal. It was a good answer, marked incorrect.)

Even just the financial concerns here are difficult to control because even SES is complex, possibly idiosyncratic. Your income doesn’t tell me your number of dependents, loans, savings, debt, security net, trust funds, expected inheritances, ability to work overtime, etc.

So, another confounded correlational study won’t solve this problem. It’s *interventions* on possible “non-ability” factors that might. If you see that interventions have effects, you know that outcomes depend on external factors.

It’s also clear that heritability of “IQ” doesn’t help either because heritable factors might not be about “ability” (e.g. preferences for certain kinds of activities, sensitivity to doing what others want or expect, etc.), but maybe that’s a story for another thread.

One important point about heritability, though, is that genes affect many aspects of your life, including what experiences you have. So even if “IQ” and genes correlate, this might be due to confounds--for instance, discrimination in educational opportunity based on how you look

Phew, almost done.

A way to summarize all this is that "ability" should mean what you do under the “optimal” circumstances for an individual, which will vary person-to-person. “Ability” is not what each person happens to bring to some boring test I just put in front of you

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C3%A1szl%C3%B3_Polg%C3%A1r

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C3%A1szl%C3%B3_Polg%C3%A1r

So, we don’t know IQ tests measure ability. We have no real reason to think they do what they claim. I sometimes get pointed to articles comparing a few other factors, but what you need is to simultaneously control *everything* in *every* claim to justify that.

When I discuss this, some people imply it's presumptuous--as though I'm claiming to resolve a century old debate. But the point is the opposite---*nobody* has figured it out.

We don't understand the functioning of a single cognitive mechanism. We don't understand C elegans. We definitely don't understand how external and internal pressures factor into test-taking performance.

And the problem in pretending that these debates somehow shouldn’t continue because they’re old or the science is “settled” (which it’s not) can be seen in the uncritical way reviewers and editors approached the Clark study. https://twitter.com/tage_rai/status/1275275891342544896?s=20

I also hear "All that's been said before!" And that's right, it has. The problem is that many basic critiques haven't been refuted or handled--they’ve been ignored. Here’s, Boykin (via the paper in @duane_g_watson’s thread above.

I suspect basic questions get ignored because people are excited to apply fancy new statistical tools, genetic tests, etc. Finally, another factor analysis. But if the underlying tests aren’t valid measures of “ability”, what's the point? What could the results possibly mean?

The dismal truth is that ignoring what test performance really means, allowing them to be built into the structure of society, leads to terrible consequences. The blame goes to psychology. An example is told through the San Francisco school system: https://www.kalw.org/post/legacy-mistreatment-san-francisco-s-black-special-ed-students#stream/0

The cross-cultural results on IQ aren’t an error or a fluke. They’re a canary. They show us the baggage that IQ tests bring. Once you see that these measures don’t do what they claim across cultures, we have to doubt that they measure what they claim within cultures too.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter