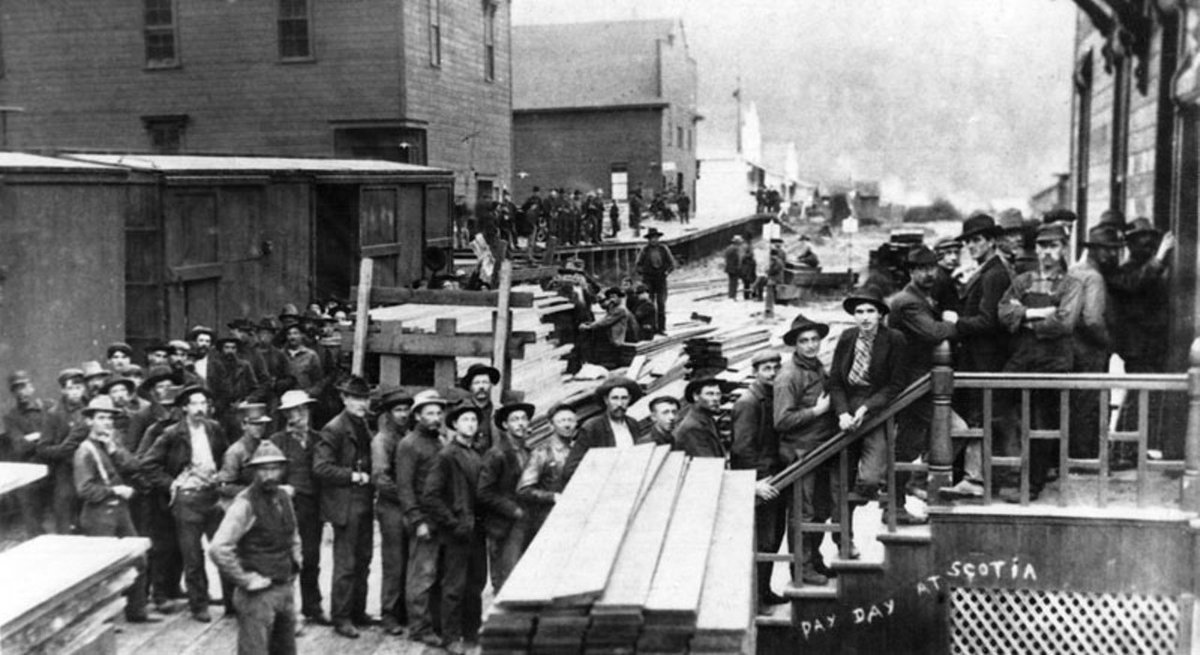

This Day in Labor History: June 21, 1935. The Eureka Mill Massacre takes place, killing 3 workers. Let's talk about the organization of the timber industry!

The Great Depression absolutely decimated the timber industry. At its best, this industry was the opposite of auto, with hundreds of operators all competing by harvesting as much timber as they could.

Overproduction and cutthroat competition was a major problem. In 1923, 495,586 people were employed in logging camps and sawmills while in 1932, only 124,997. Wages fell from an average of $19.34 a week in 1929 to $8.40 in March 1933.

A 1932 survey covering 2,320 camps and mills in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho showed that 35,250 workers had full-time employment, 29,263 had to make do with part-time work, and 58,235 were unemployed.

Loggers had a long tradition of organizing and radicalism, most notably with the IWW in the 1910s. But state repression during and after World War I, including the Everett Massacre in 1916 and the Centralia Massacre in 1919, effectively ended the IWW in the Northwest.

An industry-wide company union called the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen was created during World War I and continued on a voluntary basis after the war. But company unionism never satisfied workers’ desire for a real voice on the job.

With companies fleeing the Four-L in the early years of the depression, a new round of organizing began. The American Federation of Labor created the Sawmill and Timber Workers Union to coordinate this organizing.

While it operated on the AFL’s conservative principles, the rank and file and much of the local leadership contained thousands of radicals, including avowed communists, sowing the seeds of later internal union conflicts.

On April 26, the strike began with workers at the Bloedel-Donovan mill in Bellingham, Washington.

They had many demands, but the most important was union recognition. They also wanted a 6-hour day, paid holidays, a seniority system, and a 75 cent an hour minimum wage (about $14 in 2020 dollars).

The STWU announced a regionwide strike on May 6 if these demands weren’t granted, but workers started leaving early. They quickly followed in Portland and Olympia. By the May 6 deadline, 10,000 workers were on strike.

June 21 was the 43rd day of the Great Strike. As strikers converged on the Holmes-Eureka Mill, they began to argue with the scabs and the mill’s hired guards. People reported the police chief pull a gun and fire into the crowd, but no one is sure who fired first.

In any case, someone fired on the strikers. William Kaarte, a logging camp cook was shot in the throat and immediately killed. Tree faller Harold Edlund was shot in the chest and survived until June 24. Paul Lampella, had his eye shot out and he lingered on until August 7.

Another man named Ole Johnson had his leg amputated. This massacre would have been much worse but the police’s machine gun jammed. Sometime during this event, people broadly associated with the FBI turned up.

J. Edgar Hoover denied they were FBI agents, but it’s a good chance they were. They helped round up as many strikers as they could find. They arrested 166 workers that day. But they could not convict them, as no jury in the area would find them guilty.

The prosecutor gave up by September 25. Three days after the murders, on June 24, a mass march for the funeral of Kaarte brought 2000 people out, with representatives from all the area unions.

That might not sound like a huge funeral by the standards of the dead from strikes in cities like Detroit and Chicago, but Eureka only had 16,000 residents.

That same day, when 2000 strikers were blocking scabs at a Tacoma mill, the National Guard attacked them, leading to more violence. The growing violence of June led to both sides seeking mediation from the Roosevelt administration.

The strike had mixed success. Most employers agreed to a shorter workday and small wage increases, but refused to recognize the union. Workers returned to work in July. But they had also tasted their first victory and would continue to organize, often with radical leaders.

A general rule of thumb for this industry is that the closer you were to Canada, the more likely you were to have a communist leader. From Portland south, they tended to be more politically conservative.

The AFL had granted the United Brotherhood of Carpenters jurisdiction over the timber industry. But the Carpenters were distinctly uncomfortable with industrial unionism in the first place.

Having up to 100,000 loggers overwhelm their regular members was alarming, even as they wanted the dues. That the Northwest forests were full of radicals, including communists and ex-Wobblies was even more unacceptable.

So the Carpenters only granted the timber workers second rate status in the union. For thousands of workers, this was completely unacceptable.

With the development of the CIO, first within the AFL in 1935 and then on its own by 1937, loggers sought to create a true industrial union in the forests. This led to the International Woodworkers of America (IWA).

The Carpenters and IWA would go through a five-year war in the forests over who would represent the workers and in the end, the answer would be both, with about 2/3 of the workers with the IWA and 1/3 with the Carpenters.

Ironically, the area around Eureka would be a Carpenters stronghold and remained so for the next half-century. The IWA would win most the gains the workers in 1935 wanted, with Carpenters contracts generally following what the IWA won.

This thread borrowed from Richard Widick, Trouble in the Forest: California’s Redwood Timber Wars. Parts of it also come from my own book, Empire of Timber: Labor Unions and the Pacific Northwest Forests.

Back tomorrow with a brand new thread on the impact of the GI Bill on the American working class.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter