Do you know why the Jones Act exists? I suspect most people, to the extent they even consider the question, have some vague sense it is related to World War I . @Jeopardy offers a case in point:

#EndTheJonesAct

#EndTheJonesAct

It's true that the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 was a direct result of the war (one key matter addressed was what to do with all of the transport ships built by the government during the conflict). But why was Section 27—the actual Jones Act—included?

#EndTheJonesAct

#EndTheJonesAct

As some may be aware, restrictions on maritime cabotage are as old as the republic. So if cabotage had been restricted all along, what was the point of Section 27? Why did Senator Wesley Jones feel the need to include this provision in the Merchant Marine Act of 1920?

Before answering that question, let's go back to the first Congress. As @KLGates (the lawyers employed by the Jones Act lobby) note in their Jones Act guide, one of its first acts was to discriminate against foreign shipping in domestic commerce: https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/the-essential-guide-to-the-jones-act-25963/

So were the Founding Fathers a bunch of protectionists? Context here is important. For starters, ensuring a large fleet of U.S. merchant ships was vitally important to U.S. national security, as such vessels could function as a naval auxiliary.

During the recently-concluded Revolutionary War, for example, U.S. privateers (converted merchant ships) captured or destroyed around 600 British ships.

Furthermore, both U.S. shipping and shipbuilding were very competitive: https://www.cato.org/books/case-against-jones-act

Furthermore, both U.S. shipping and shipbuilding were very competitive: https://www.cato.org/books/case-against-jones-act

Indeed, they were so competitive that in The Abandoned Ocean ( https://www.amazon.com/Abandoned-Ocean-History-United-Maritime/dp/1570034273), authors Andrew Gibson and Arthur Donovan argue that these measures favoring U.S. shipping were essentially cost-free.

To say that is no longer the case today is a gross understatement.

To say that is no longer the case today is a gross understatement.

In 1817, meanwhile, U.S. policy went from discouraging foreign ships in domestic trade via discriminatory duties to flatly prohibiting them.

#EndTheJonesAct

#EndTheJonesAct

As the decades passed the age of wood and sail gave way to iron and steam. Ensconced in their protected domestic market, U.S. shipbuilders did not adapt. After the famed clipper ships it was pretty much all downhill for both U.S. commercial shipbuilders and the U.S. fleet.

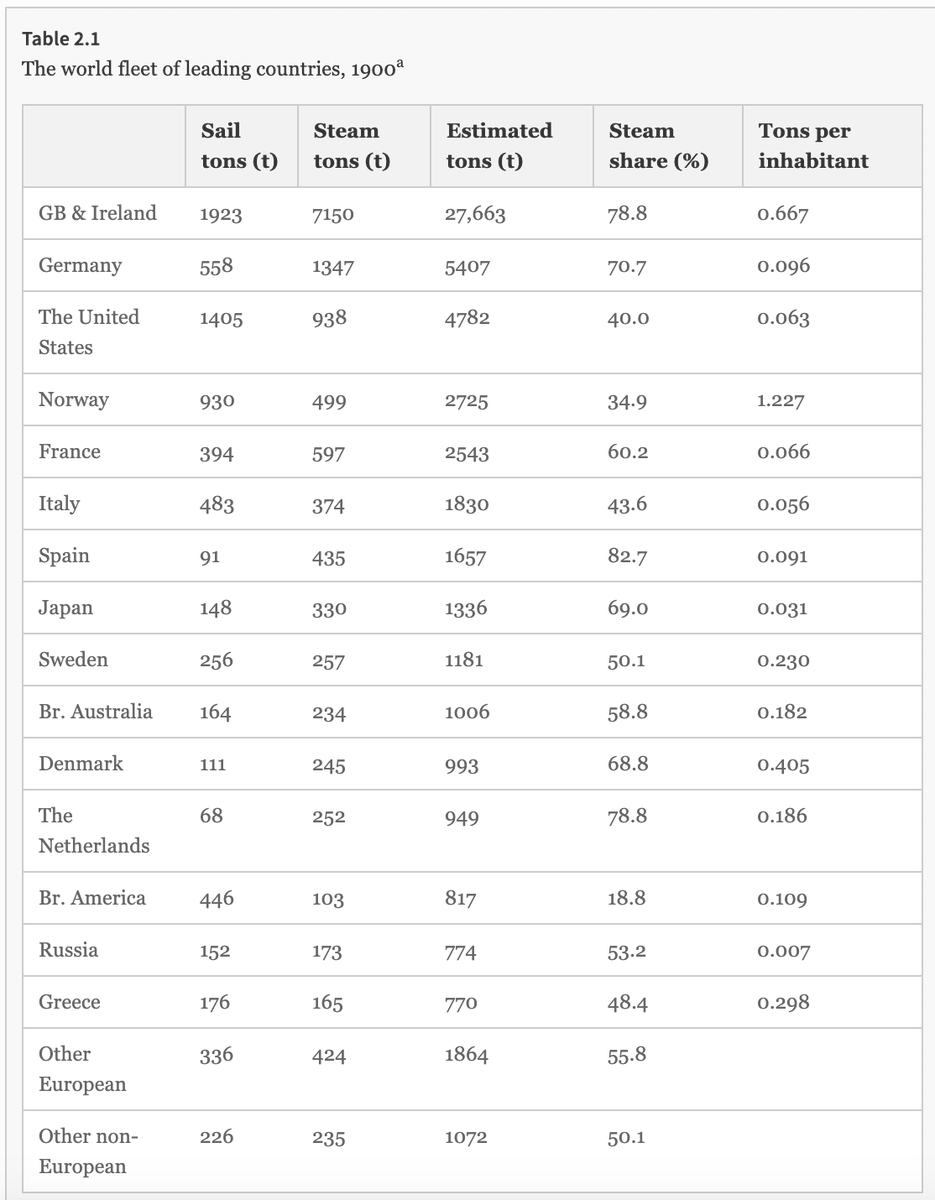

This is illustrated by the fact that by 1900 the U.S. had only 40% of its tonnage under steam power and the rest under sail. In contrast, numerous other countries had as much as 70% or 80% under steam: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-26002-6_2

U.S. shipping became so uncompetitive that in the early 1890s a shipper tried sending 250 kegs of nails from NY to California via *Belgium*, as breaking the journey into two international voyages would allow the use of foreign shipping.

#EndTheJonesAct

#EndTheJonesAct

This resulted in a court case examining whether the shipper had violated U.S. coastwise laws against foreign ships engaging in cabotage. The court ruled that the shipper did not. So Congress responded by prohibiting domestic trade via voyages through foreign ports.

But in the face of uncompetitive U.S. shipping, the search went on for less costly alternatives. One option that emerged was sending goods overland to a foreign port and then on to its US destination as travel by land was not deemed to be a "voyage."

#EndTheJonesAct

#EndTheJonesAct

So goods destined for Alaska from the Lower 48 could first be sent by rail to Vancouver and then on to AK. This competition was great for AK, but not so good for Seattle shipping companies. These companies, however, had an ace up their sleeve: their state's senator, Wesley Jones.

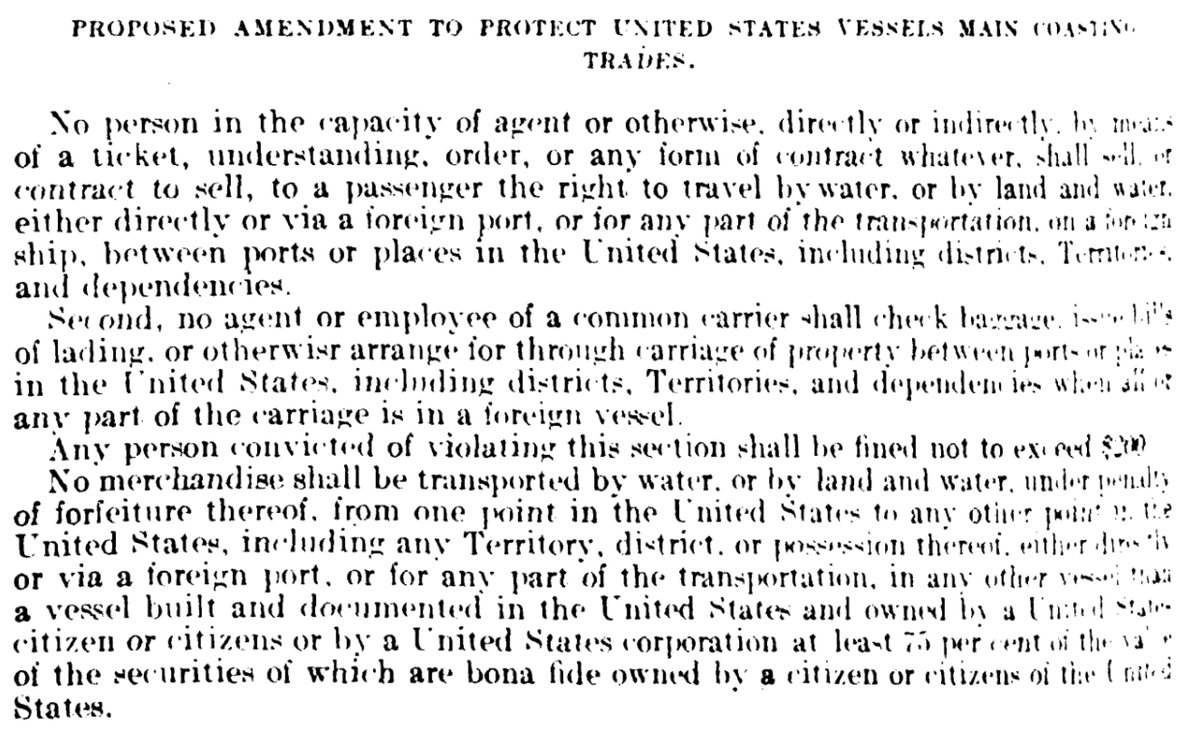

On February 20, 1920 William L. Clark of the Pacific Steamship Company testified before a hearing chaired by Sen. Jones where he complained about this competition from Canada. To head this off Clark proposed the following amendment to U.S. coastwise laws: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3475999&view=1up&seq=1462&q1=clark

Here's what ultimately made into the Merchant Marine Act of 1920's Section 27, with additions to the existing cabotage language in italics and deletions in strikethrough:

Readily apparent is the similarity to Clark's proposed language, as evidenced by terms such as "by land and water," discarding the term “ports” in favor of the broader “points,” and a reference to vessels “built in” the United States.

#EndTheJonesAct

#EndTheJonesAct

This is just the most basic version of the history behind the Jones Act. For a more complete story, pick up a copy of "The Case against the Jones Act." https://www.cato.org/books/case-against-jones-act

#EndTheJonesAct

#EndTheJonesAct

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter