Human Sacrifice as a Biblical Practice

Many will tell you that the Israelites did not practice human sacrifice to Yahweh. The evidence is to the contrary. There is a bias toward this claim because our view of that ancient people is colored by the biases of Abrahamic claims.

Many will tell you that the Israelites did not practice human sacrifice to Yahweh. The evidence is to the contrary. There is a bias toward this claim because our view of that ancient people is colored by the biases of Abrahamic claims.

This is a topic I had intended address from the start. Human sacrifice is in the Bible, particularly the Old Testament or Tanakh. Some cases are well known, but it is actually much more common than most know. Language and translation conceal an important concept.

This concept is the Hebrew word "cherem"(חרם). This word is often translated in ways that conceal the religious context. "Utterly destroyed", "banned", and etc. This term has a religious context first and foremost. An important rule about it is laid down in Leviticus 27:28-29

"Devoted to destruction" is how "cherem" is translated here. It applies to humans, property, and animals. In Latin, it is translated as "devotio" and in Greek "anathema". Both of those terms meant "sacrificed to a god" in their original context. The translators knew what it meant

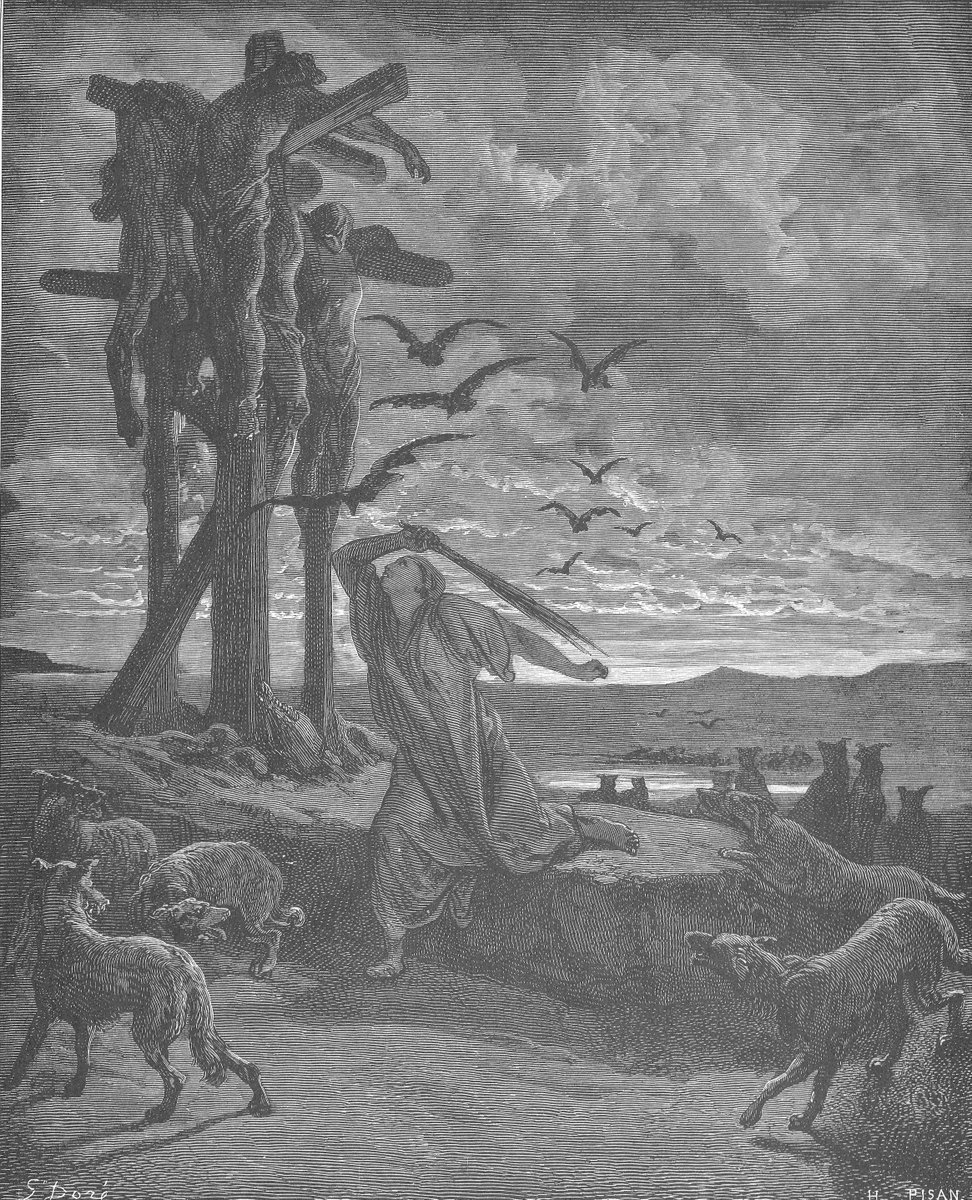

Not only are humans included in what can be "cherem", they very often are in the text. And where it is not the term used, there is a very strong implication of this idea. Take the example of David offering up Saul's children and grandchildren to end a famine in 2 Samuel.

I have read a lot of Christian commentaries and apologetics. No amount of sophistry is going to make me think that is not a sacrifice. If anyone else but the Hebrews took a group of men to a "hill of god" to kill them so it would end a famine, it would be called human sacrifice.

Nothing about the victims is mentioned, just that they were related to Saul. How convenient though, that David could eliminate all of Saul's male descendants, save for his his crippled grandson. Saul's heir Ishbaal was also conveniently murdered in his house, well before this.

There is also the famous case of Jephthah. He vows a sacrifice to Yahweh of whatever comes out to greet him, if he defeats the Ammonites. It ends up being his own daughter, and he sacrifices her. The Hebrew and Greek used is unambiguous about this.

Some have tried to say otherwise. But that is trying to change what it says. The command of Yahweh is that no one devoted as a sacrifice can be redeemed. They can't be spared or exchanged, they must die. Which is exactly what happens here.

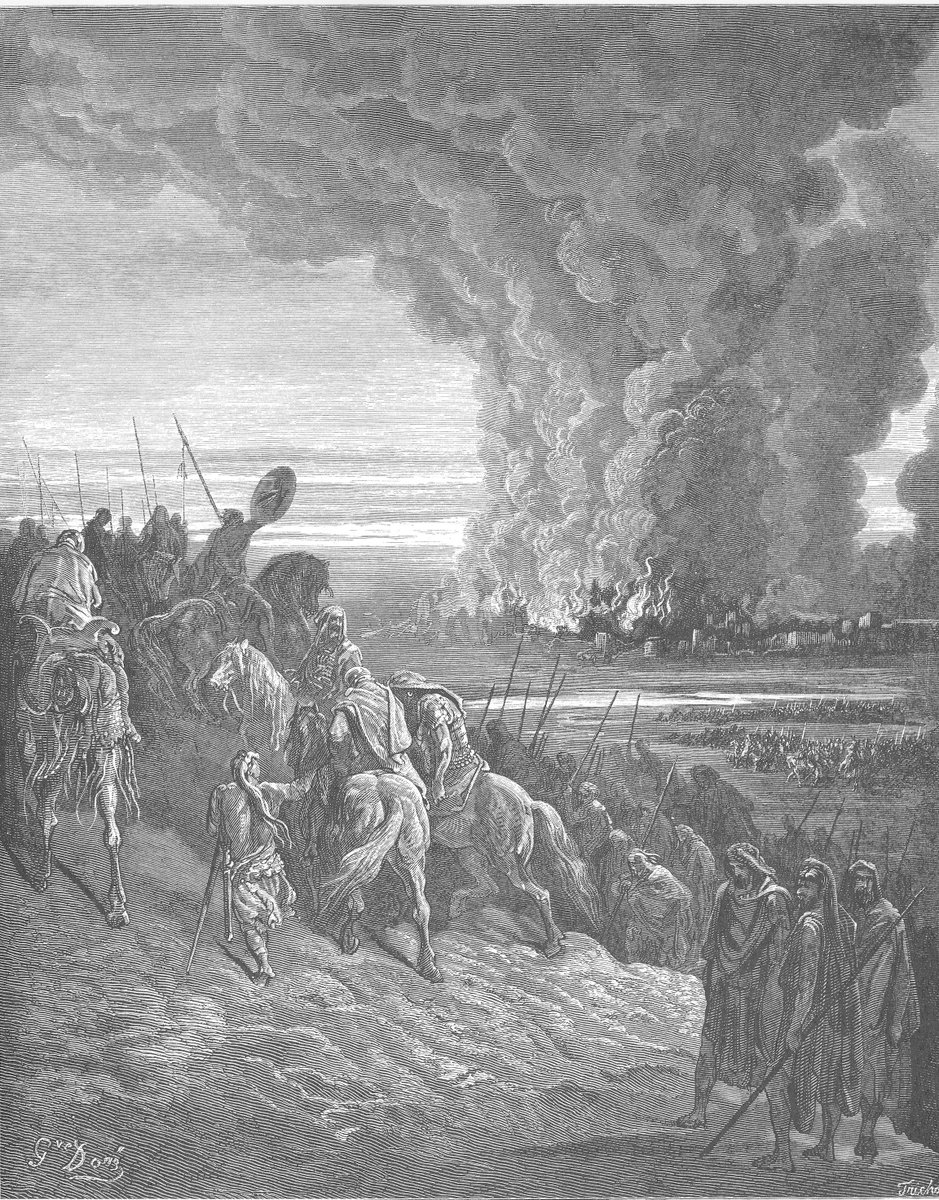

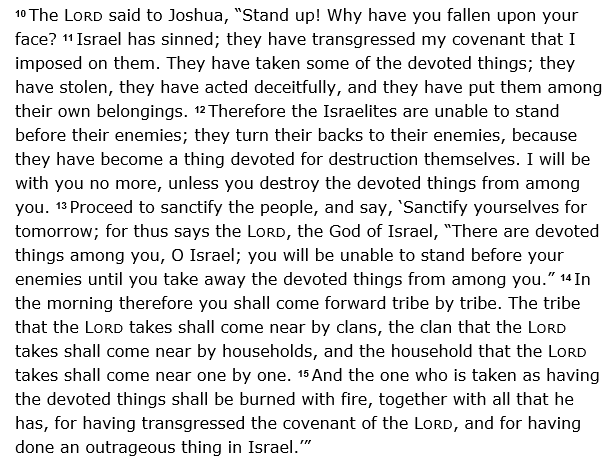

Another example is the case of Achan and his family. The Israelites sacrifice the entire population of Jericho, along with their valuables and animals. The sacrificial nature of "cherem" is the reason animals are included in all those Biblical massacres. It was a mass offering.

Achan had held back some loot that was suppose to be devoted, leading to Joshua losing cleromancy to determine who was guilty. The lot fell on Achan. The language in Joshua 7 indicates that taking a "cherem" object makes everyone in the group also become "cherem".

Joshua does what he is told. Achan, along with his children, possessions, and livestock, are stoned and burned. This appeases Yahweh's anger because of Achan having kept things that were meant to be offerings to him. This was not considered unjust, as it was a matter of cherem.

There is another close example in 1 Samuel 14. Engaged in war, Saul makes a vow that anyone who eats before the day is up will die. His son Jonathan eats some honey, ignorant of this vow. Some kind of cleromancy from Yahweh reveals to the priest that someone has transgressed this

It turns out to be Jonathan. The only thing that stops Saul from killing his son is the objection of his troops. This case is ambiguous, but makes more sense in light of cherem and the seriousness of vows. Otherwise, why would Yahweh indicate to Saul that he should kill his son?

Another case is the slaughter of the Amalekites. Samuel tells Saul to slay the Amalekites, animals, babies, women, children, all of them. The word used is again, "cherem". That is the reason why it has to be so merciless, and the reason for what happens after. Saul messes up.

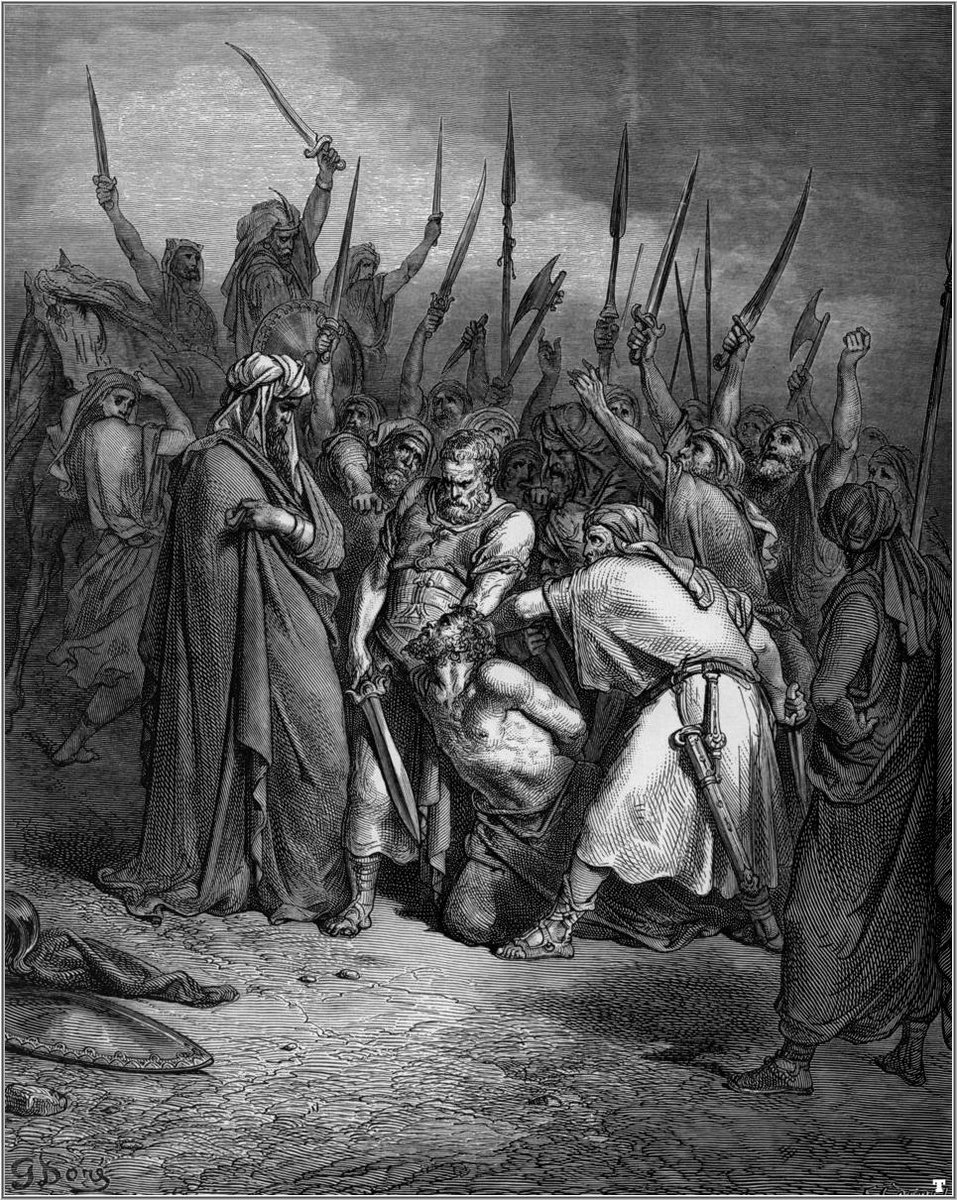

He spares the king of Amalek and some of the choice livestock. Samuel is angry with him, and curses Saul that he will not be king for long. Saul says that he was taking the king and animals to the altar of Yahweh at Gilgal. Samuel doesn't care.

Cherem meant that all that belonged to Yahweh anyway, and Saul had just denied him his offerings. A similar offense to Achan, actually. Samuel corrects it by finishing the job. He hacks Agag to pieces at Yahweh's altar. A small plea for mercy does not move him.

"Cherem" was a practice of other Semitic peoples. The Mesha Stele shows that the Moabites did the same thing, and it uses the same word for it(Moabite was basically a dialect of Hebrew). Note how "sacrifice" is used here, it would not be used in the Bible

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/anet/320-the-stela-of-mesha/

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/anet/320-the-stela-of-mesha/

I have looked at a transcription of the Phoenician letters on the Stele. Incidentally, the Hebrews used the same alphabet until they adopted their current one from the Persian era Aramaic script. It reads 𐤄𐤕𐤌𐤓𐤇𐤄, or "the cherem" Everyone was killed for the Moabite god.

Things changed. The entire Levant was ruled by successive empires that would have frowned on cherem. The rabbis were troubled enough by it that they changed cherem to mean a type of excommunication. This made its way into Christianity as anathema, the Greek translation.

There is a final issue to bring up. The Bible has a fixation on sacrificing children, particularly by fire and especially firstborns. This is strange in a culture that we are told started off as utterly opposed to such practices. Ezekiel 20:25-26 says that Yahweh commanded them.

Jeremiah wrote that Yahweh never approved such sacrifices. That wouldn't need to be said, unless the sacrifices were to Yahweh. In any case, cherem still entails the sacrifice of children. It seems like semantics to condemn one form of child sacrifice and approve another.

"Mlk" is a Semitic root indicating "king", or "ownership" and may have designated an offering. The later commentators may have invented or misconstrued a god called "Moloch" in Israel from that root to obscure Yahweh's associations with the sacrifice of the firstborn.

There were other cultures that at least occasionally did this. The Greeks and Romans mentioned some Phoenicians doing this. The rabbis likely based the hollow Moloch statue in the Talmud on older Roman and Greek accounts of Carthaginian sacrifices. They are identical in form.

There is no other religious text that commands at least 5 times in one section alone not to sacrifice your firstborn. The Egyptians never did this, and apparently did not need laws against it. Neither did others. The Hebrews did. Clearly it loomed large in their recent past.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter