Alfred Hitchcock thread

The Pleasure Garden: Though not regarded as thoroughly Hitchcockian, Hitchcock's first picture, as Dave Kehr has pointed out, is filled with signs of things to come. A spiral staircase, voyeurism, a blonde who turns out to be a brunette: all appear in the opening scene alone.

The story pairs two flapper-type young women, one of whom becomes a stage star, with two colonial officials. The girl who hits the big time runs off with a prince; the other does get married, but her husband turns out to be dallying with a native lass over in the unnamed colony.

Caught in the act when his wife arrives unannounced, the man drowns his mistress, who then reappears as a ghost (pictured below in a GIF I didn't expect to find in Twitter's library). This does seem un-Hitchcockian, given his apparent avoidance of anything obviously supernatural.

The Lodger: I can't think of early 20th-century London without thinking of boarding houses. Maybe a disproportionate number of Londoners of that era really did live in boarding houses, but now I wonder how much of that image owes to how often they appear in early Hitchcock.

A Jack the Ripper tale told with Jack the Ripper still in living memory, The Lodger has its title character arrive at a boarding house looking and acting just like everyone expects the much-discussed murderer to look and act — so much so that he cannot possibly be the Ripper.

Disappointingly, the film makes it clear that the lodger isn't Jack the Ripper. I've read that Hitchcock originally intended to leave it ambiguous, to keep the possibility open that the heroic young man who wins the landlord's daughter in the end may actually be a serial killer.

There's nothing ambiguous, however, about how the young Hitchcock uses the film to announce himself as the next big talent. The London fog, the glass floor, the blinking "GOLDEN CURLS" sign: you can feel all of it pushing the established language of silent cinema to its limits.

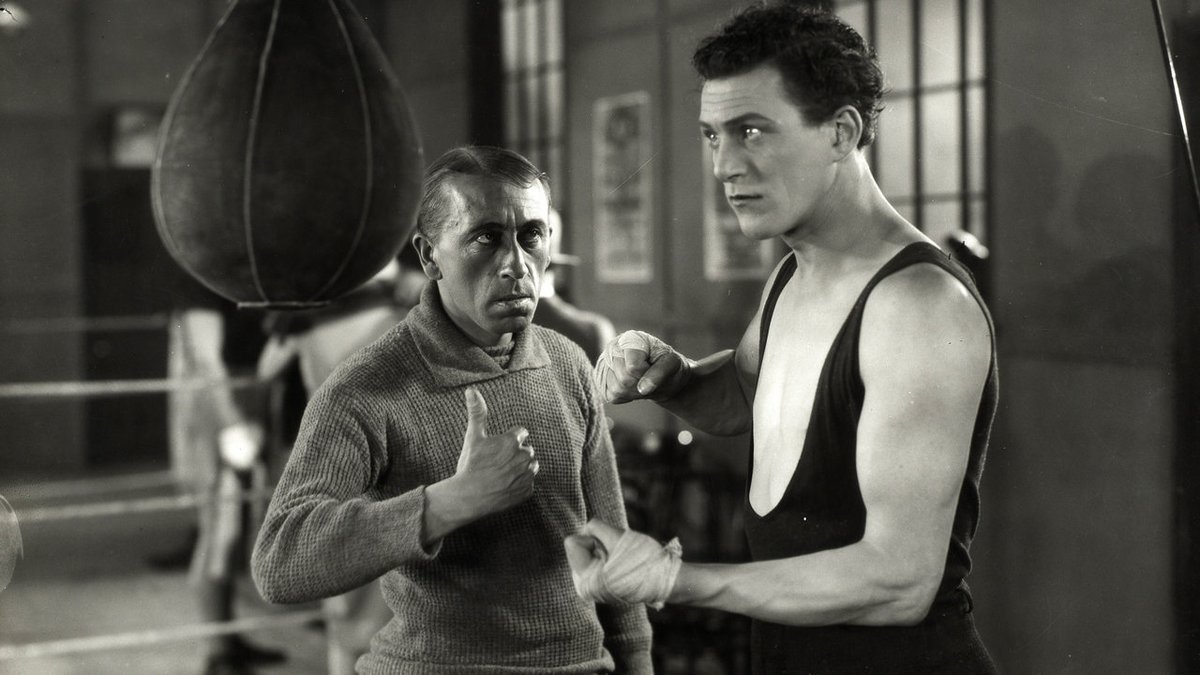

The Ring: I didn't known Hitchcock made a boxing movie, though I was aware of the genre's unavoidable silent-era popularity. Any up-and-coming young director would have expected to be given at least one pugilistic picture, although this one was an original Hitchcock screenplay.

When boxing movies fell out of favor, such up-and-comers also lost a reliable means of demonstrating their technical mastery. Martin Scorsese revived this move 55 years later with Raging Bull, and he must have been the last to successfully pull it off. https://twitter.com/colinmarshall/status/1215100518743166977

Casual Hitchcock-watchers will spend the whole time waiting for a murder, inside or outside the ring. The movie isn't Hitchcockian in that way, but as Éric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol write, "it permits Hitchcock a very subtle treatment of a theme that is dear to him: adultery."

(And yes, if you've guessed that I'm watching Hitchcock's entire filmography in large part to enable a richer reading of Rohmer and Chabrol's book about his first 44 pictures, you are right.)

Downhill: The title reflects the direction of the life of the protagonist. A boarding-school boy takes the fall for his best friend when a flapper accuses them (seemingly both of them) of having impregnated her. Expelled, he later stumbles into a doomed marriage to an actress.

Not long after the union falls apart, our man finds himself working in the kind of place from which no 1920s Hitchcock character emerges unscathed: a music hall. And a French music hall at that, France being the country where (so I gather) most fallen Englishmen used to wash up.

He's working there as a sort of ballroom-dancing gigolo for leering middle-aged women, and even that's not the end of his fall. The accompanying metaphors include a southward geographical journey, and he winds up all the way in Marseilles before someone puts him on a ship home.

Leering middle-aged women were no doubt a fact of professional life for Ivor Novello, the film's star and co-writer of the original play. Previously the lodger in The Lodger, he was known as Britain's handsomest screen actor in the 20s; Downhill more or less puts him on display.

The 34-year-old Novello doesn't make a very convincing schoolboy, though I can't say for sure how old the character is supposed to be at the end. Has his downfall taken a year? Five years? A decade? Six months? I'd believe any answer, given the story's subjective sense of time.

What title cards appear provide surprisingly little dialogue. Three of them divide the film into parts: first "The World of Youth," then "The World of Make-Believe," and finally "The World of Lost Illusions" — not the only elements that suggest aspiration toward universal myth.

The Farmer's Wife: The eponymous character dies in the first scene, leaving the farmer to spend the remainder of the film in search of a new wife. He draws up a list of local widows and spinsters, then rides around proposing to — and being rejected by — each of them in turn.

None of these prospective wives is particularly appealing to begin with, and they become even less so after the farmer calls on them. He gets frustrated enough to inform one of them that she's "full blown and a bit over," which triggers a shrieking, all-limbs flailing meltdown.

The film has the clear goal of finally uniting the farmer with his faithful young housekeeper, a goal handily accomplished. "The point of view is that of a man who enjoys his domestic comforts," write Chabrol and Rohmer, "but it is also that of a man in love with femininity."

Working with an adapted stage play, Hitchcock uses his cinematic advantage to show off the Welsh (from what I've read) countryside. Perhaps that explains the sequence toward the end, of otherwise unclear purpose, with hundreds of beagles led through the village out on a fox hunt.

Easy Virtue: After a high-profile divorce trial involving the accidental death of her portraitist and would-be lover, an Englishwoman on the cusp of middle age escapes to the Mediterranean. There she soon finds herself proposed to by a young Englishman unaware of her identity.

When the two return to the young man's family estate in England, they've already married. Sensing something amiss, his mother proceeds to put pressure on her son's new bride, going so far as to keep his last girlfriend around the house. Eventually, of course, all is discovered.

The basis is a Noël Coward play, seemingly written to send up the haughty moral attitudes of the English gentry. But in the movie no character comes off particularly well, and and whatever signature witticisms Coward worked into the script don't make it into the sparse dialogue.

The satire is as moralistic as its target: "'Virtue is its own reward' they say, but 'easy virtue' is society's reward for a slandered reputation." Apparently the bien pensant of 1928 also had to pretend that easy virtue and slandered reputation were things of no consequence.

Champagne: Not very Hitchcockian in any obvious respect, this one showcases "the British Mary Pickford" Betty Balfour much as Downhill does Ivor Novello. She plays an heiress who hires a plane out to go see her boyfriend on an ocean liner, drawing the wrath of her rich father.

Dad suddenly shows up claiming that the family has lost everything — a fortune made in the champagne business — after a market crash. (This was just a year before the real 1929 crash of the London Stock Exchange.) So when the ship arrives in France, they just have to stay there.

As Hitchcock later said to François Truffaut, Champagne "had no story to tell." It had, at any rate, more to show than tell: not so much Balfour herself (a British Mary Pickford in every sense) but a variety of visual tricks — match cuts, a freeze frame, etc. — unique to cinema.

Truffaut clearly learned from Hitchcock's freeze-frames. And the evident technical mastery required to pull all this off does suit the thin material, although the film's entire legacy seems to have amounted only to the improbable through-a-glass-bubbly final shot.

In the exchange just before, the heiress and her boyfriend declare their intent to get married. The latter suggests having the captain marry them on the ship back to England: presumably one of the Cunard Line's, as was the ship that took them to France in the first place.

Cunard Line still exists, albeit as a subsidiary of the cruise juggernaut Carnival. But no longer are any of its ships registered in the United Kingdom: in 2011 they moved all the licenses to Bermuda, where couples can legally be married at sea. I guess that's where the money is.

The Manxman: Hitchcock's last silent film is a remake, or rather the second adaptation (the first, now lost, came out in 1917) of the eponymous novel by Hall Caine, a Manx writer from whose meddling Hitchcock ultimately had to relocate his shoot off the Isle of Man to escape.

Whether shot on location or in Cornwall, the setting is remarkably elemental compared to Hitchcock's earlier work. In it plays out the story of a love triangle between two best friends, the fisherman Pete and the lawyer Philip, and Kate, the daughter of the local pub's owner.

Kate promises to marry Pete before he goes to seek his fortune in Africa. Philip looks after Kate in Pete's absence — and of course the two wind up falling for one another. No sooner does word of Pete's death come in than they scamper off for some alone time in an isolated mill.

This turns out to be fake news: Pete is in fact alive, but by the time Philip hears of it, Kate is already pregnant. In this third Hitchcockian tale of downfall, no choice remains for the disgraced daughter and just-bewigged judge than total self-abasement, followed by exile.

A sense of the sublime elevates potentially melodramatic subject matter, and the combination of relative visual and narrative austerity make this, for me, the most memorable of Hitchcock's silents. (So does an inventive use of not just titles but letters, telegrams, diary pages.)

Blackmail: We arrive at Hitchcock's first sound film — indeed, the first British sound feature ever made. Like many pictures of that era, its sparse dialogue is (to my ear) seldom perfectly intelligible. But it doesn't matter, given that the project was conceived as a silent.

More to the point, it doesn't matter because the director is Alfred Hitchcock. You could consider him a silent filmmaker who successfully made the transition to sound, but he has much more value to us as a sound filmmaker with the visual storytelling ability of a silent master.

Like Easy Virtue, Blackmail features a young woman implicated in the death of a painter. She goes home with him, but when he gets too close for comfort she stabs him with a bread knife and flees. It transpires that her boyfriend, a Scotland Yard detective, is assigned the case.

Walking through London, this woman is tormented by insistent visual reminders of her guilt — corpse-like sleeping bums, dagger-like blinking advertisements — and aural ones too, as in the boarding-house scene where the soundtrack turns up the volume only on the word "knife."

Her boyfriend (misguidedly) protects her, but soon a seedy figure turns up claiming to have evidence that she committed the murder. His attempt to commit the titular form of extortion doesn't survive the exposure of his own criminal record, and the movie then turns into a chase.

This final pursuit through (and atop) the British Museum marks, by my reckoning, another Hitchcock first: the first of the climactic spectacles that deliver much of his filmography's immediately memorable imagery. (Here it also kills off the blackmailer, exonerating the blonde.)

The opening, which depicts the detective and his fellow officers arresting a suspect unrelated to the main story, seems inessential. But it was meant to serve a superior, unused ending in which the detective, in a similarly another-day's-work fashion, puts away his girlfriend.

Juno and the Paycock: An adaptation of a stage play about a hard-up Dublin family who come into money — or at least believe they have — during the Irish Civil War. It was popular enough in the theatre of the 20s and 30s that I've seen it referenced in a few novels of that period.

The popularity of the play seems to have carried over to Hitchcock's cinematic version — as it must have, since Hitchcock's version is barely cinematic at all. Even without knowledge of the source material, any viewer can tell they're watching little more than filmed theatre.

It must have been tempting, when sound came along, to simply covert successful works for the stage into movies. No need sweat visual storytelling when the actors can tell the story themselves! The result: "pictures of people talking," as Hitchcock himself later dismissed them.

Murder!: The titular event happens just before the film begins. An actress is discovered in a near-catatonic state beside the bludgeoned body of another actress. The viewer immediately rules out the straightforward suspicion of her being the Murderer!, but the jury doesn't.

Or rather, most of the jury doesn't. One member acquainted with the actress, in show business himself, holds out a while. After the conviction he strives to prove her innocence, though unlike most of Hitchcock's accused she displays notably little interest in the matter herself.

Late in the film emerges its most memorable character, a trapeze artist desperate to keep secret not his cross-dressing, which he does to play female roles onstage, but his "half-caste" origins — in all a veiled way, it's been argued, of suggesting homosexuality in 1930s Britain.

Told with extensive dialogue even by the standards of later Hitchcock, the story (whose every main character is some kind of theatre professional) uses a fake script to expose the real Murderer! — whose metaphorical and literal fall delivers the visual spectacle at the very end.

The Skin Game: Another adapted stage play, this one about a grudge match between two moneyed families in the countryside, the aristocratic Hillcrists and arriviste Hornblowers. The head of the Hornblowers wants to develop land near the estate of the Hillcrists, who won't have it.

On balance the film's sympathies seem to lie with the Hornblowers, cinema itself having still been an arriviste medium at the time. But even so, it stops short of ridiculing the Hillcrists, whose iron resolve to prevent the appearance of "chimneys" at all costs raises the stakes.

As far as I can tell, the Hillcrists embody a genuinely extant near-fetishistic English attitude toward "untouched" countryside land. The aristocratic perspective has a good deal to recommend it, to my mind, though I can't say I share any of its kneejerk preference for the rural.

Though the film remains essentially theatrical, Hitchcock cinematically enlivens certain passages. Most impressive for me is the auction of the land in question, which opens with an unbroken 80-second shot from the constantly crowd-scanning perspective of the auctioneer himself.

Rich and Strange: This one opens with an evening-commute sequence that, despite its function of conveying the misery of the protagonist's workaday existence, still makes the London Underground of the early 1930s look superior to many a transit system in the United States today.

When the man gets home, a letter arrives from a wealthy uncle informing him that he and his wife will receive part of their inheritance in advance, expressly so that they might enjoy themselves in the moment. And so they embark on the Oriental cruise that structures the film.

Many of Hitchcock's later films are noted for the sheer amount of ground they cover, albeit usually because their characters are fleeing pursuers. Here we have a married couple following a travel itinerary; the drama arises from that perennially Hitchcock-favored theme, adultery.

The wife, Emily, wastes little time taking up with a Navy Commander on the ship. Once he recovers from seasickness, the husband, Fred, starts pursing "a Princess!" Or so the title cards describe her in this sound film that puts more text onscreen than many of Hitchcock's silents.

Actually, what arises from all this is better described as comedy than drama: the "princess" is obviously a grifter, and the bachelor Commander, though seemingly a man of genuine rank, surely can't keep his promise to settle down, much less with the suburban likes of Emily.

Hitchcock would again find comedy in the material of a couple driven temporarily apart by sheer boredom. This is also a travelogue film, incorporating footage of Paris, Port Said, Colombo, and Singapore (the last three of which they see, humorously, only from cars and rickshaws).

That Fred and Emily will reconcile is a foregone conclusion, though even when they do Hitchcock has more peril in store. That the film's ending must nevertheless find them back in their Garden-City home underscores the weakness of genre — not this genre per se, but genre itself.

Number Seventeen: Another theatrical adaptation, albeit one that ends with a train crashing onto a boat. But most of what happens before that climactic chase happens in an empty house, working through the logic of a convoluted story about the pursuit of a stolen diamond necklace.

The film's two segments, as critical consensus seems now to hold, sit together uneasily. Personally, I admire the starkness of the aesthetic contrast between them, though the toy-set spectacle of the second rather drowns out the gunshots-and-pratfalls chamber farce of the first.

I shouldn't exaggerate the discontinuity between what takes place inside the house and on the train, building as the action in the former does to a pursuit of its own. (Not that the ever-growing number of characters and revelations about their identities makes it easy to follow).

Nor should I make the train sequence sound rinky-dink, when in fact it must've been a technical marvel in 1932. On repeat viewing, I see Hitchcock pulls it off with fewer model shots than I'd remembered. And it gives me reason to learn about train ferries: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Train_ferry

Waltzes from Vienna: Here we have Hitchcock's only attempt at a period biographical romantic comedy/operetta film — and not an especially serious one, if his own on-set declaration is to be believed: "I hate this film, I hate this kind of film, and I have no feeling for it."

The story is adapted from an Austrian musical (or something formally between a musical and an opera) about Johann Strauss II writing "The Blue Danube" in defiance of both his famous, egotistical father and a baker's-daughter fiancée who doesn't want him getting above himself.

Minor, uncharacteristic, and near-disowned a work though this may be, I do admire the boldness of taking a musical as source material and removing all the songs. This also sharpens the focus on "The Blue Danube" — a piece still 34 years from being associated with Stanley Kubrick.

The Man Who Knew Too Much: Exotic location? Check. Murder? Check. Kidnapping? Check. International crime? Check. Sun-worshipping cult? Check. Final set-piece shootout? Check. MacGuffin? Check. It seems Hitchock made the prototypical thriller film rather early in his career.

I have little direct experience of the thriller genre in film. I have practically none at all in literature, but that hasn't stopped me from — and may have encouraged me toward — reading about thrillers, in books like @AndyMartinInk's Reacher Said Nothing: https://twitter.com/colinmarshall/status/1160455634254327808

You could say this 1934 The Man Who Knew Too Much (Hitchcock would do a loose American remake in 1956) doesn't quite hang together, except as string of individually spectacular elements — none more so to me than Peter Lorre's ability to deliver his English lines phonetically.

With a film like this, I find myself trying to recall the eventful plot in detail, knowing full well how little it matters. Much like the the MacGuffin, a device Hitchcock first employed here (as a note warning of an assassination), it's all just excuses to keep the action going.

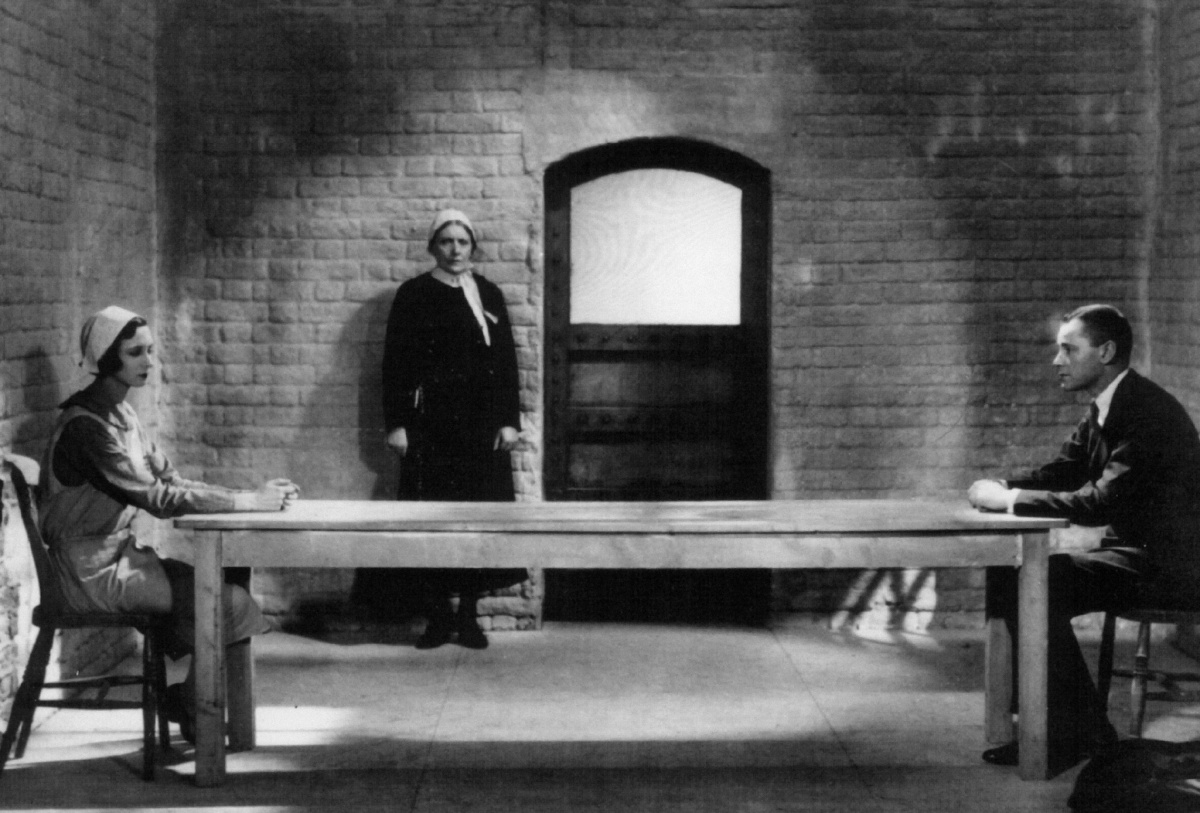

The 39 Steps: The purest expression so far of that most Hitchcockian scenario of all, an innocent man on the run alternately helped and hindered by an immaculately costumed blonde. Here the innocent man is Canadian, unusually, though a Canadian in Hitchcock's territory of London.

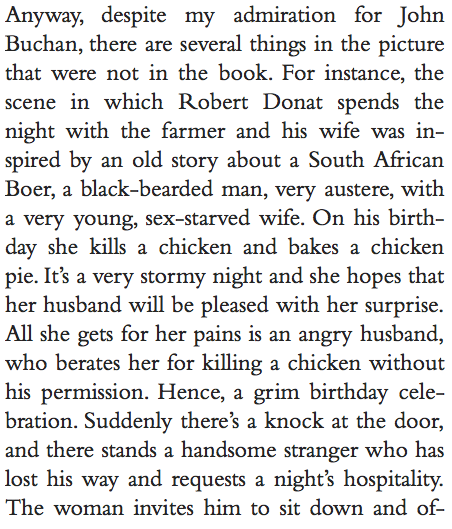

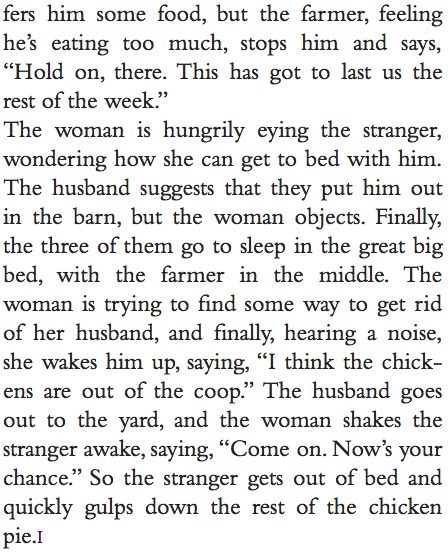

Naturally he's soon pursued out of London, in accordance with Hitchcock's ever-widening geographical purview. He makes it all the way to Scotland, where the film executes perhaps the canonical hide-out-in-a-farmhouse-for-the-night sequence. Hitchcock tells a good related story:

In a field where the competition includes Gregory Peck and Cary Grant, even a 1930s British cinema icon like Robert Donat hasn't gone down in history as a preeminent Hitchcock leading man. Yet he defines the qualities essential to such a figure, not least an iron self-possession.

By the same token, The 39 Steps defines much of what became essential to the Hitchcock thriller. I admire its cinematic engineering — but there's also something unforgivable, to my mind, about being what Robert Towne called the origin of all "contemporary escapist entertainment."

Secret Agent: Odd that a Somerset Maugham adaptation starring John Gielgud should come out as a less-than-respectable Hitchcock film, albeit one exotically set (in a Swiss Casino, the Swiss Alps, a Swiss chocolate factory, a train crossing into Turkey) and filled with incident.

You could call this an "entertainment," as Graham Greene preemptively labeled his less ambitious novels, though on some level Hitchcock made nothing but. Greene himself, who wrote film criticism in the 1930s, had little appreciation for Hitchcock, and less still for Secret Agent:

In some sense a comedy, the film also acknowledges the wearying qualities of the secret-agent genre. Gielgud is one of a trio, the others being Peter Lorre and "Hitchcock blonde" Madeleine Carroll," who signed on for adventure but has second thoughts when they kill the wrong man.

Sabotage: Hitchcock returns to London, and though the action never leaves the city, it happens as a consequence of international intrigue. A cinema owner commits the titular acts as an agent of an unnamed and vaguely motivated foreign power, Tsarists in Conrad's original novel.

As in many Hitchcock adaptations, the source material's story is simplified nearly to the point of abstraction. Creating one suspenseful situation after another is the goal. In the most famous, a schoolboy unwittingly carries a bomb onto a bus — and actually gets blown up by it.

Hitchcock later said he thought he'd botched that scene, narratively speaking. He also acknowledged the miscasting of the boy, and worse, of the detective charged with investigating all this sabotage. Yet the film did win over even the formerly Hitchcock-detracting Graham Greene.

Greene approves of the boy blowing up as a retention of "the ruthlessness of the original." I'd side with him more than I would with Hitchcock, who regretted that the sequence as designed had made the public "resentful" — awareness of the public being his great virtue and vice.

Young and Innocent: This title could apply as well to the protagonist as to the murder victim. Spotted standing over the corpse when it washes up on a beach, the former is accused — and in the media declared guilty — of having killed the latter. Naturally, he goes on the run.

Just as naturally, this being Hitchcock, the evasion of his pursuers (all humanity, it seems) takes him deep into the countryside. Of course, he falls in on the way with a blonde (or blonde-enough) who, despite initial hostility, becomes his ally — and eventually his lover-to-be.

The film's most lasting cinematic move comes near the end, as a correlative for the whole search for The Real Killer up to that point. A single crane shot makes its way over a ballroom to musicians onstage, among whom he's identified by his facial twitch.

This protagonist, like most of Hitchcock's up to this point, isn't much of a character beyond his youth, and more to the point, his innocence. But had he been anything more, perhaps the audience couldn't have projected onto him their invincible convictions of their own innocence.

The Lady Vanishes: Hitchcock has made use of trains fairly often up to this point, but here we have a film most of whose action takes place on a train. And it is right off of that train, while it travels through a vague Alpine middle-Europe, that the titular lady vanishes.

There are two ladies, a young one and the old one. It's the latter who vanishes, though not before befriending the former — who then, in increasing distress, finds that everyone and everything has seemingly conspired to insist to her that there was no old lady in the first place.

At once, a Hitchcock fan suspects two things: first, that there was indeed a lady, and second, that the lady didn't actually vanish. The audience must be misdirected at every opportunity, and here the first opportunity comes in the title, now the film's best-remembered element.

The young lady is the protagonist, not usually the female part in Hitchcock's thrillers. But then she isn't a blonde, and like so many of Hitchcock's doggedly pursued men, she's thrust into a situation where all seem to be against her, with precious few allies to be found.

Modern viewers would surely describe the other passengers' behavior as "gaslighting," although some of them just have a cricket match they don't want to miss or a mistress with whom they don't want to be discovered. Incidentally, the play that term comes from the same year, 1938.

All was not well in Europe at that time, of course, a condition that has begun to make itself felt in Hitchcock's work. The "vanishing" of the lady is ultimately tied to a bit of nonspecific spy-vs.-spy gamesmanship, complete with a MacGuffin and a final shootout at the border.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter