By the spring of 1918, the First World War was into its fourth year. A weary British population had lost fathers, sons, uncles and friends all fighting on the battle fields.

Life was hard on the home front too, where a deadly influenza virus spread resulting in the deaths

Life was hard on the home front too, where a deadly influenza virus spread resulting in the deaths

of thousands of civilians. The death toll was less than a third of the 750,000 British fighting personnel who died in the war, and a fraction of the estimated 50 million people who died worldwide throughout 1918 and 1919, but the shock of it echoed throughout communities.

ScotlandsPeople registers record and mirror the epidemic that claimed the lives of thousands of victims in Scottish towns and cities.

Newspapers, reluctant to spread more bad news, only quietly reported the epidemic. The influenza took the name ‘Spanish ‘Flu’ because the

Newspapers, reluctant to spread more bad news, only quietly reported the epidemic. The influenza took the name ‘Spanish ‘Flu’ because the

media were able to report on the epidemic sweeping the neutral country of Spain.

The flu arrived in Britain via ports in Glasgow. The original source is still a mystery – some contemporaries believed that it originated in the far east, others in the unhygienic and

The flu arrived in Britain via ports in Glasgow. The original source is still a mystery – some contemporaries believed that it originated in the far east, others in the unhygienic and

overcrowded British military camp at Étapes in France.

Wherever it began, it was a universal experience; the shipping networks freely transported the illness across the world. Servicemen and travellers stepped off the ships onto Clydeside, unwittingly spreading the virus.

Wherever it began, it was a universal experience; the shipping networks freely transported the illness across the world. Servicemen and travellers stepped off the ships onto Clydeside, unwittingly spreading the virus.

Railways helped the flu to travel locally; urban and coastal areas - those well-served by mass communication and transport links - suffered worse than the rural, inland and isolated areas across the country.

As the flu spread, an alarmed public questioned the cause of the

As the flu spread, an alarmed public questioned the cause of the

epidemic and sought preventative methods. Doctors were unsure about what advice to give. The Southern Reporter newspaper noted on 31 October 1918 that

‘…the very considerable reduction of sugar and fat in the national diet has weakened the power of resistance of the

‘…the very considerable reduction of sugar and fat in the national diet has weakened the power of resistance of the

individual… the whisky drinker says the seat of the trouble is the scarcity of his favourite spirit; across the Border some allege that the poor and thin quality of the beer is at the bottom of it. The smoker asserts that a perpetual cloud of tobacco smoke ensures immunity

from infection, and the sniff-taker has steady belief that no microbe can exist where the mull is in constant request. One set of opinions is perhaps just as reliable as another. What we are up against is that the disease exists and is spreading.’

Local newspapers promoted

Local newspapers promoted

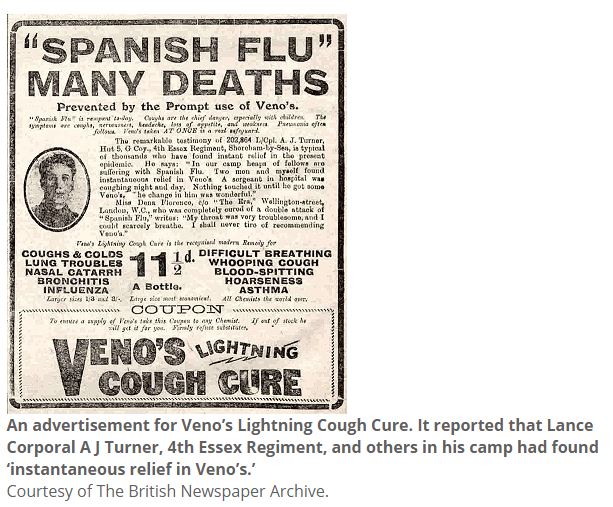

and advertised remedies. ‘Zip’ cold remedy claimed that it could dry up a common cold within half an hour, and could therefore prevent the ‘flu from setting in. ‘Formamint’ advertised their mints with the support of aristocratic ladies including Lady Mann who stated

she ‘felt safe from infection of any kind when I have Formamint at hand.’ Lady Firbank agreed that ‘Formamint tablets have completely cured [my] throat which owing to influenza has been left weak and painful.’ ‘Veno’s Lightning Cough Cure’ boasted that

The illness swept the country in three waves – the first, in the early summer of 1918 was the mildest and mainly claimed the very young, elderly and sick. The second wave in the autumn of the same year attacked a different sector of society. Half of the deaths from this

phase of the outbreak were people aged between 20-40 years old. It wasn’t unknown for healthy adults to die within a day of catching the virus. The third, in the late winter in early 1919, was also powerful and produced a high mortality rate.

Over five months in late 1918,

Over five months in late 1918,

the registered deaths in Scotland numbered 14,742, more than the corresponding five months of the previous year. The deaths in 1917, by comparison, had been the lowest in all the years since 1868.

The Registrar General for Scotland’s yearly report covering 1918 recorded

The Registrar General for Scotland’s yearly report covering 1918 recorded

that 78,372 deaths (39,144 male and 39,228 female) were registered in 1918. The report confirmed that at least 17,575 deaths that year were attributable to influenza. This was probably an underestimation; some deaths were ascribed to other causes and complications due to the

presence of influenza, for example, ‘bronchitis’ or ‘pneumonia’.

In the early stages of the epidemic, deaths were often attributed to ‘PUO’ (a pyrexia of unknown origin) but later deaths were recorded as ‘Spanish Flu’ or, more commonly, ‘influenza.’

In the early stages of the epidemic, deaths were often attributed to ‘PUO’ (a pyrexia of unknown origin) but later deaths were recorded as ‘Spanish Flu’ or, more commonly, ‘influenza.’

The victims of the disease were mainly from ill-nourished working class families. The Perthshire Advertiser reported on 13 July 1918 that the flu ‘usually begins with a sharp attack, an out-and-out seizure, and even doctors have had to stop short in their rounds of visitation

and go to bed. The most effective remedies are said to be quinine and toddy.’

Some victims suffered from ‘heliotrope cyanosis’ which was evidenced in blue markings on your fingertips, lips, nose and tips of your ears. Bodies were known to turn black due to de-oxygenated

Some victims suffered from ‘heliotrope cyanosis’ which was evidenced in blue markings on your fingertips, lips, nose and tips of your ears. Bodies were known to turn black due to de-oxygenated

haemoglobin in the blood vessels.

Although the influenza was most dangerous for young adults, no one was immune. The Perthshire Advertiser in July 1918 reported on the death ‘an elderly lady Miss Scott, residing at Aldie Place Dunkeld Road. Miss Scott was 78 years old.’

Although the influenza was most dangerous for young adults, no one was immune. The Perthshire Advertiser in July 1918 reported on the death ‘an elderly lady Miss Scott, residing at Aldie Place Dunkeld Road. Miss Scott was 78 years old.’

The flu pandemic came to an end by the summer of 1919 as those that had been infected had either died or developed immunity to the virus. In the 100 years since the Spanish flu outbreak, there have been four influenza pandemics, but none were as deadly as the 1918 outbreak.

Source - SP & NLS

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter