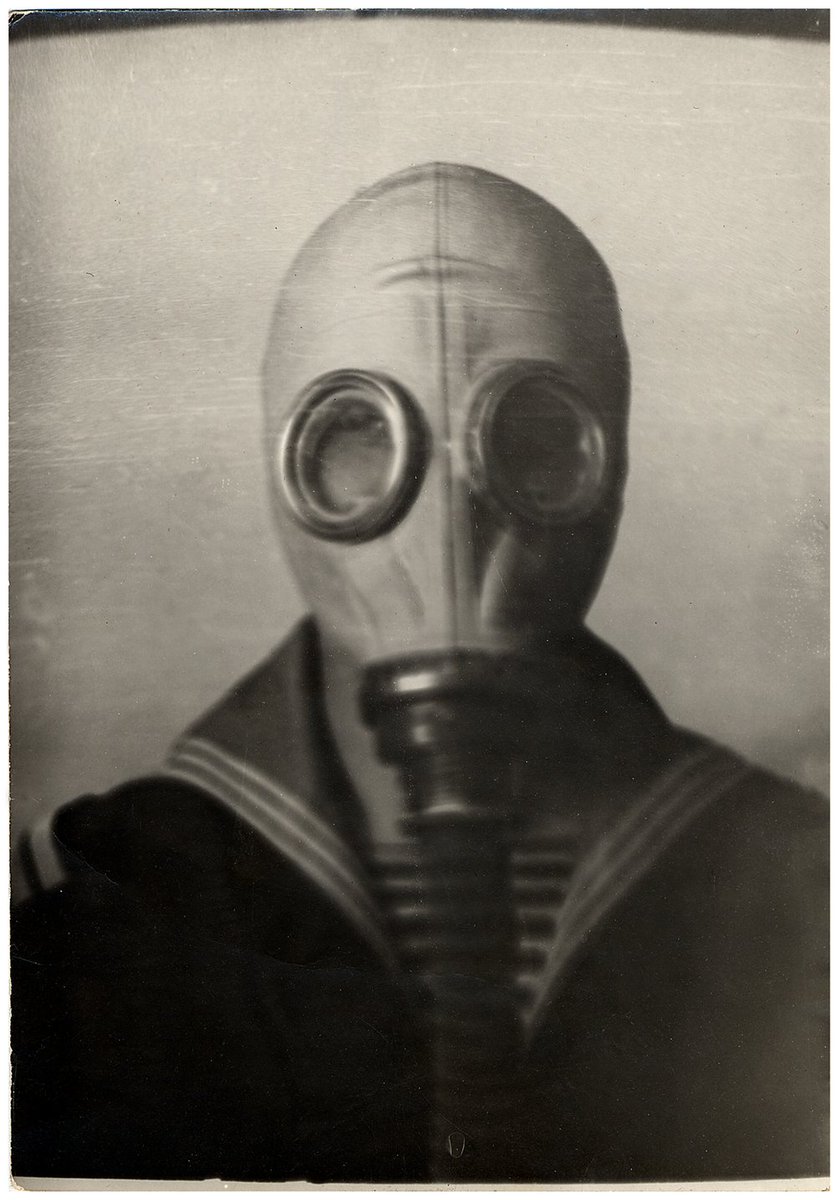

It is claustrophobic: the sound of your own breathing mixes with the fear of asphyxiation.

It is impersonal: only the eyes peering through the sockets betray any humanity.

It is totemic: the sum of our fears, and for some - their desires.

This is the history of the gas mask...

It is impersonal: only the eyes peering through the sockets betray any humanity.

It is totemic: the sum of our fears, and for some - their desires.

This is the history of the gas mask...

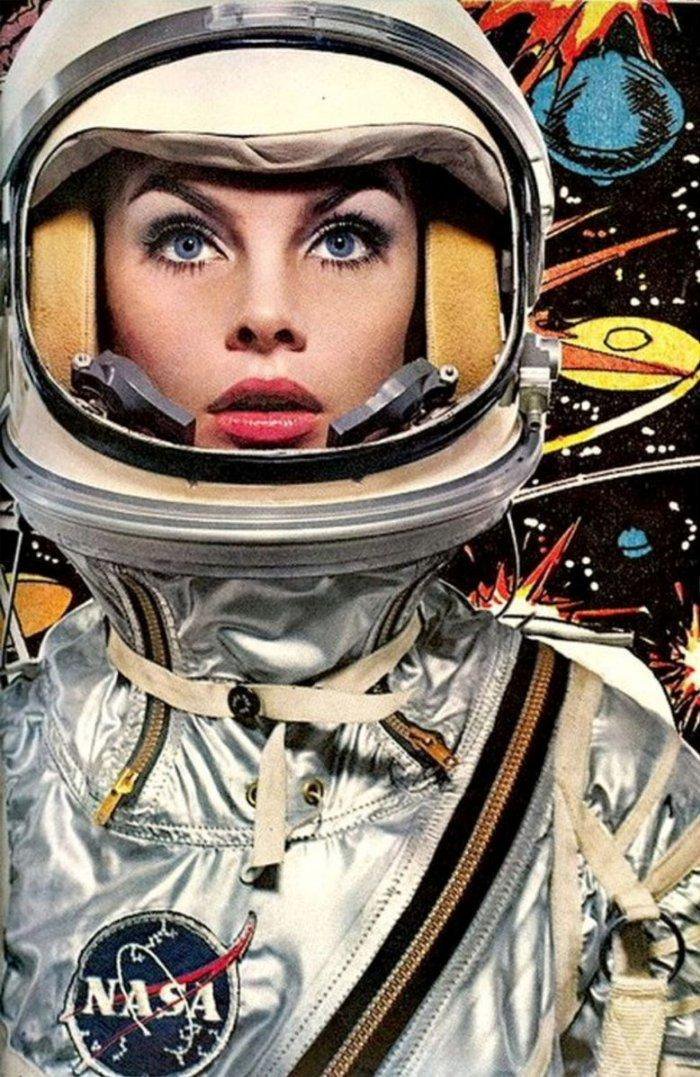

If the spacesuit is the symbol of progress, the gas mask is the sign of the apocalypse. In popular culture it signifies that science has turned against us. It's the face of dystopia.

The first chemical masks were work by Venitian plague doctors: a bird-like mask, the beak stuffed with lavender, matched with full length coat and hat. It was a terrifying sight - the grim reaper come to apply poultices to your tumours.

But it was poison gas, first used at the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, that led to the modern gas mask. At first these were cotton masks treated with chemicals. However their protection was limited.

Eventually a full hood design with an activated charcoal filter was developed, the mask linked to a respirator worn on the chest. This image of these inhuman soldiers soon became the frightening face of modern industrial warfare.

But soldiers were not the only victims of gas attack: horses, mules and dogs also needed protection. The medieval and the industrial world seemed to fuse together in the mud and death of the Western Front.

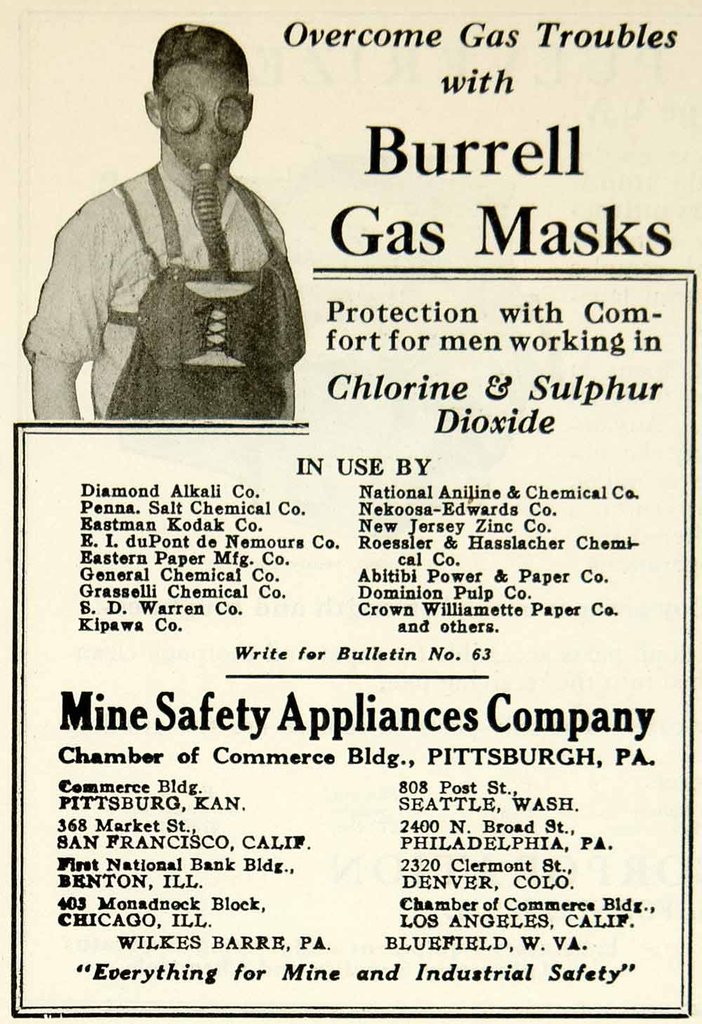

After the Great War gas mask technology was reused for civilian purposes. Miners were issued them for protection in hazardous conditions. It was the beginning of what would later become the Hazmat suit.

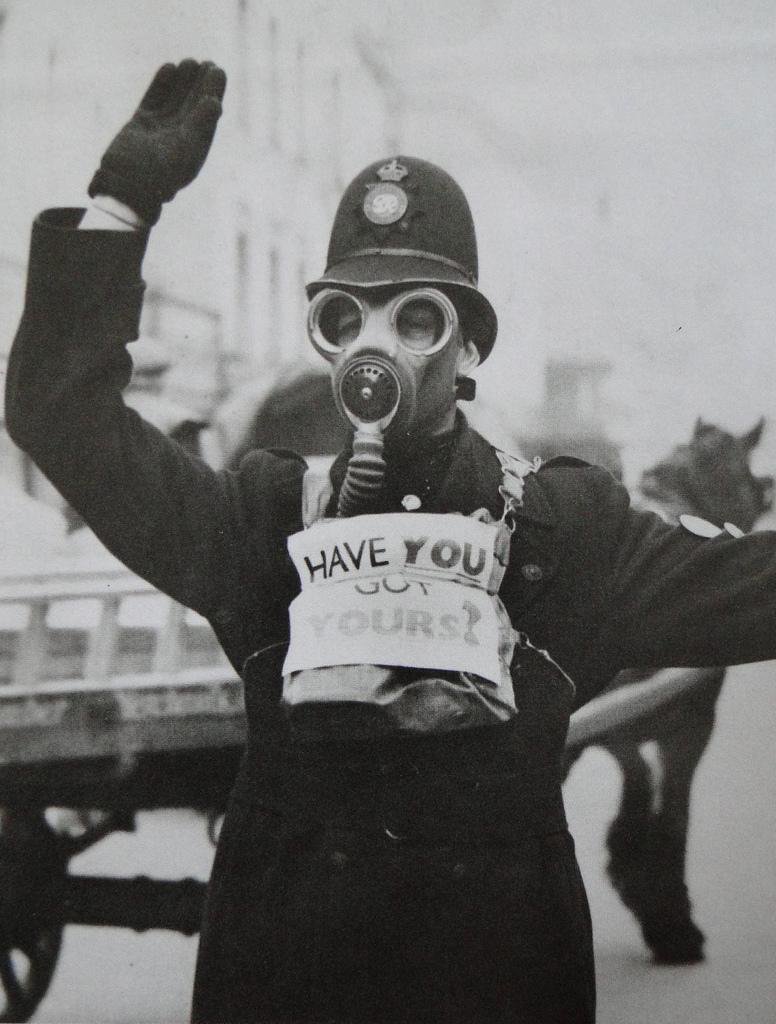

By the outbreak of World War Two the fear of gas attack from German bombers led to widespread deployment of gas masks and hazmat suits on the home front. Britain lived in morbid fear of destruction from chemical warfare.

People tried to adapt: children were given 'Mickey Mouse' gas masks to lessen their fear of them. Comedians made jokes about them. They were normalised, made commonplace. Humour diffused the fear.

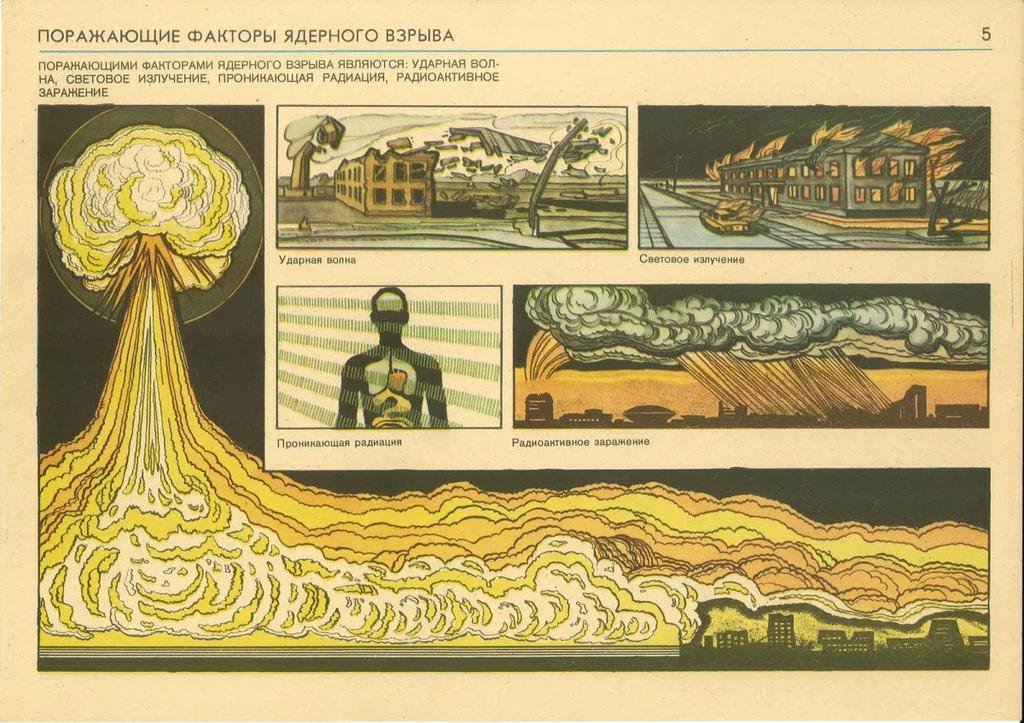

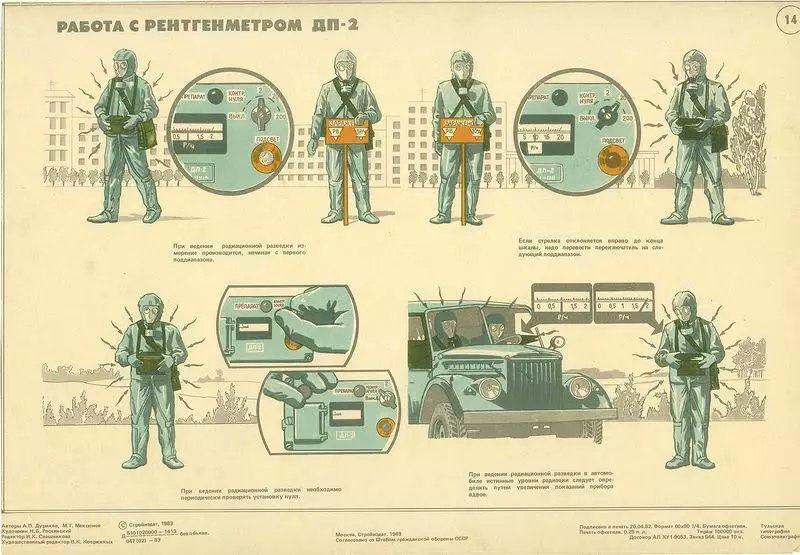

And then the atomic bomb was dropped. A new threat required a new protective response: the gas mask (now with filter attached directly to the mask), hazmat suit and dosimeter became part of the new normal for troops. The era of the NBC soldier had arrived.

Then by the middle of the century something strange happened: having been normalised by war, the gas mask began to be embraced by alternative culture as a sign.

And like many signs it pointed to many things...

And like many signs it pointed to many things...

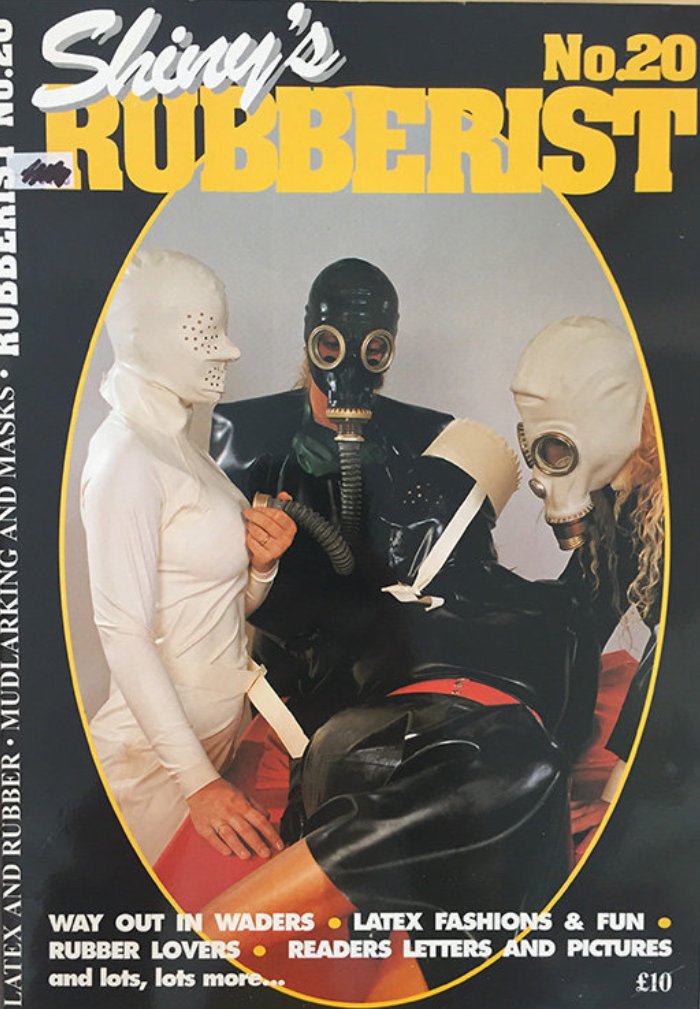

Rubberists are people who like wearing rubber: sometimes draped, sometimes tight fitting. The gas mask - enveloping and constricting - was a natural fit for the scene.

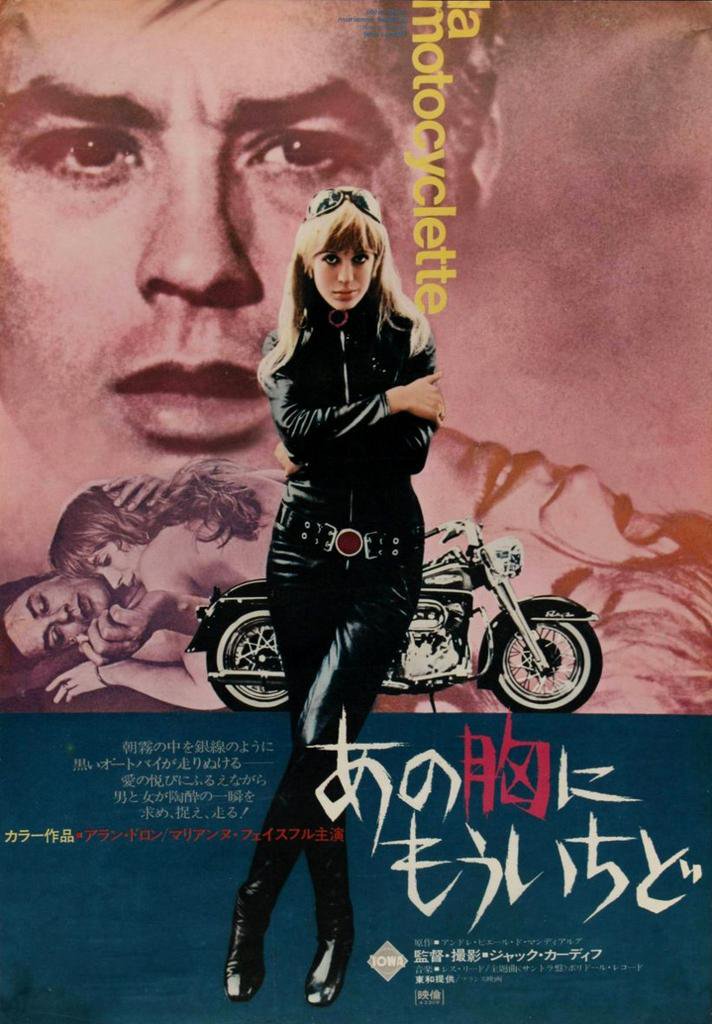

John Sutcliffe was an early pioneer of leather, rubber and latex fetish clothing. Starting out in Hampstead in 1957 he later designed the tight biker clothing for Marianne Faithful and latex costumes for A Clockwork Orange.

Sutcliffe's company - Atomage - relocated to Drury Lane and began publishing a number of influential fetish magazines, which the police regularly confiscated and burned. The gas mask as fetish item began to take off.

Like all fetishes there is a question mark over whose desire is being stimulated: the subject or the observer. Many readers of Atomage wrote in to say they hated gas masks, and only wore them to give their partners pleasure.

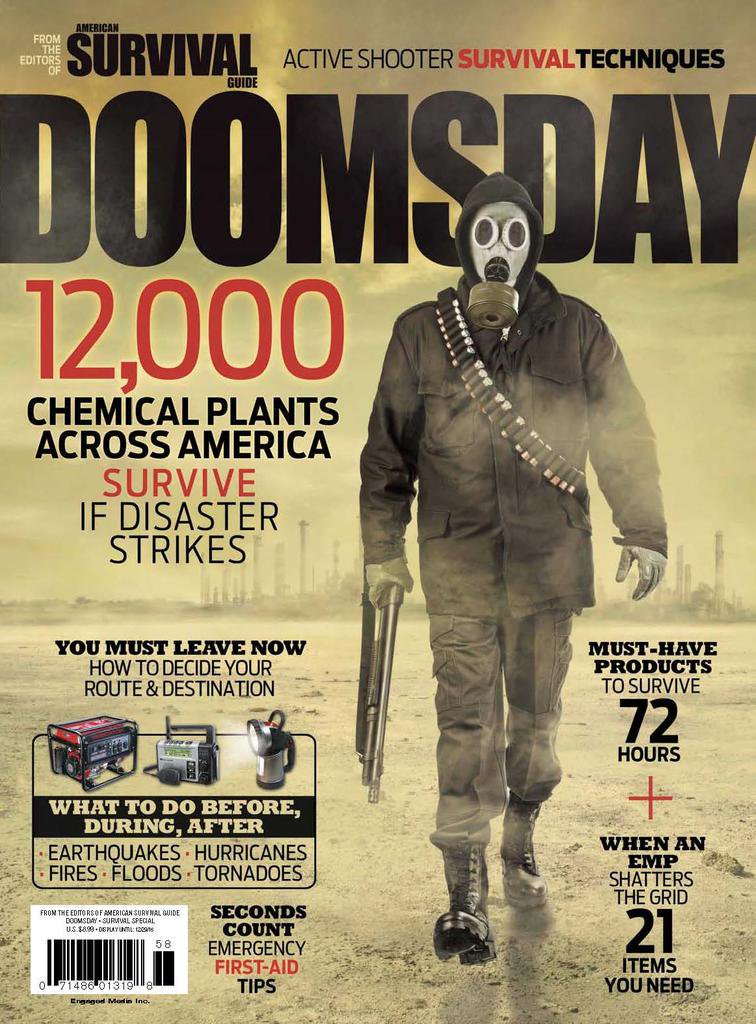

Survivalists are people who anticipate and prepare for civil emergencies. Developed from the Civil Defence movements of the 1950s they are sometimes called 'Preppers': people prepared for the worst.

Survivalism was boosted by the 1970s oil shocks and the widespread civil discontent of the time. And as the Cold War reheated in the 1980s some people genuinely believed that Doomsday was a matter of when, not if.

Companies began to cash in on this fear by selling military-grade protection equipment to civilians. Modern respirators were certainly safer than WW2 era gas masks, and more comfortable too.

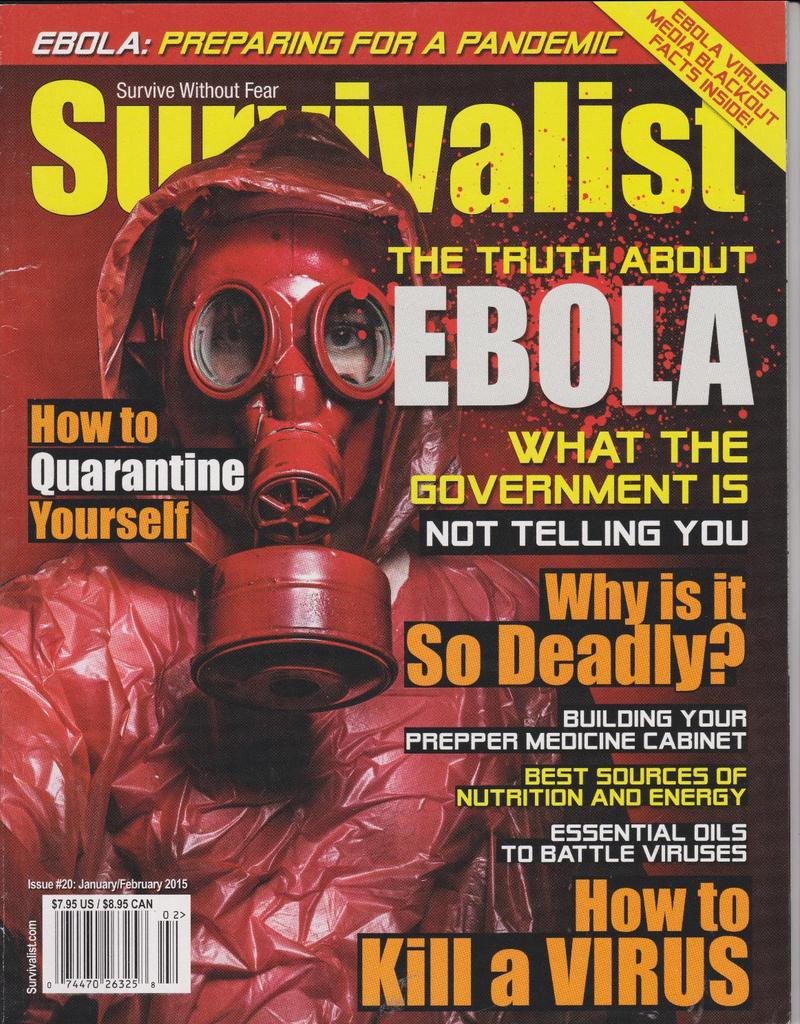

As the Cold War ended, Prepper concerns turned to other hazards: pandemics, bio-terrorism and plague outbreaks. Eventually these fears would feed into the emergence of Zombie Apocalypse fiction as a popular genre of pulp.

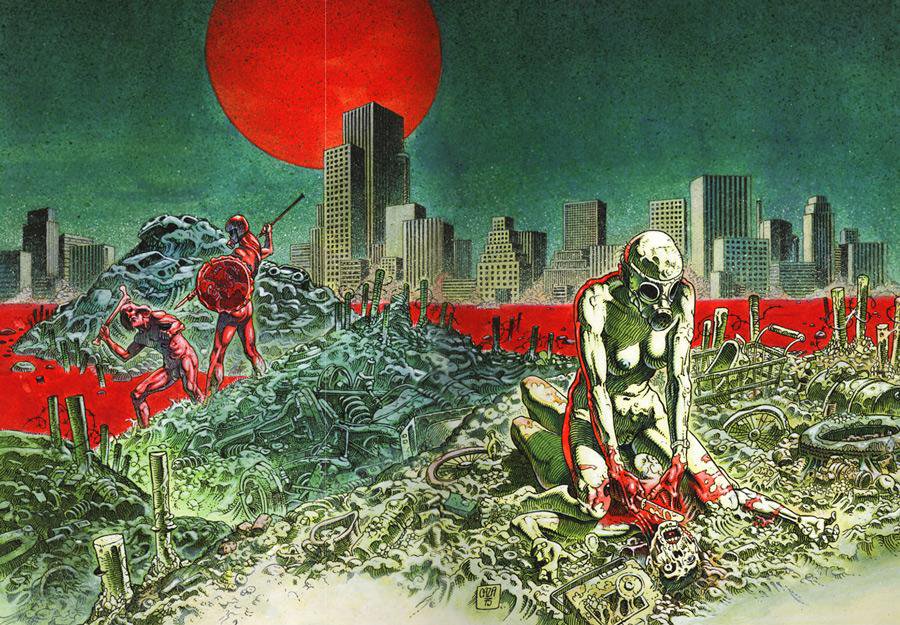

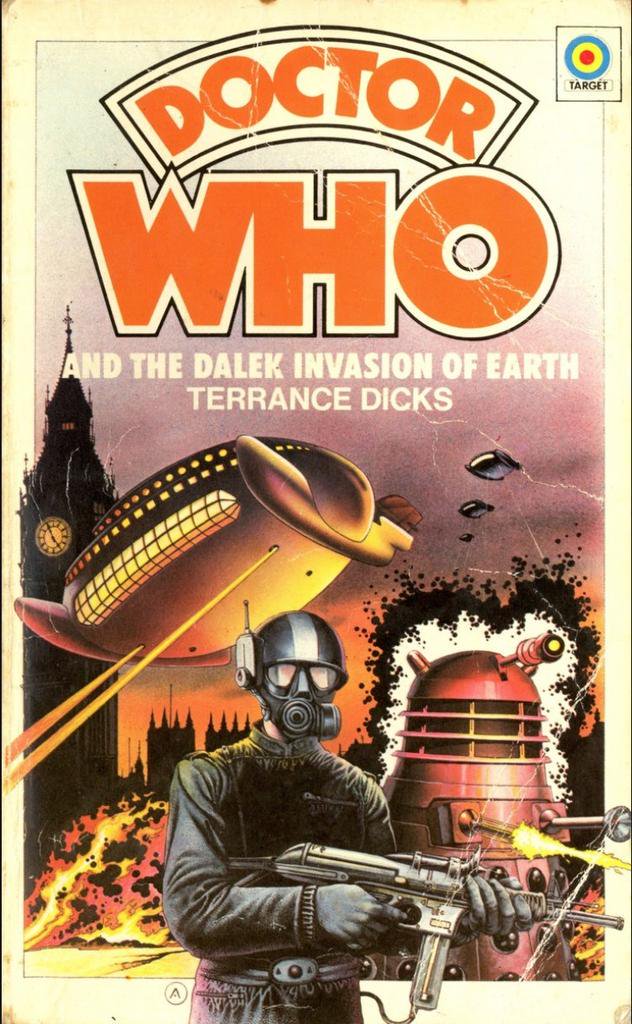

Bio-hazard has been a popular sci-fi theme for a long time, from War Of The Worlds to I Am Legend. And in the 1970s one artist fused the rubberist and survivalist look into a new aesthetic of the apocalypse...

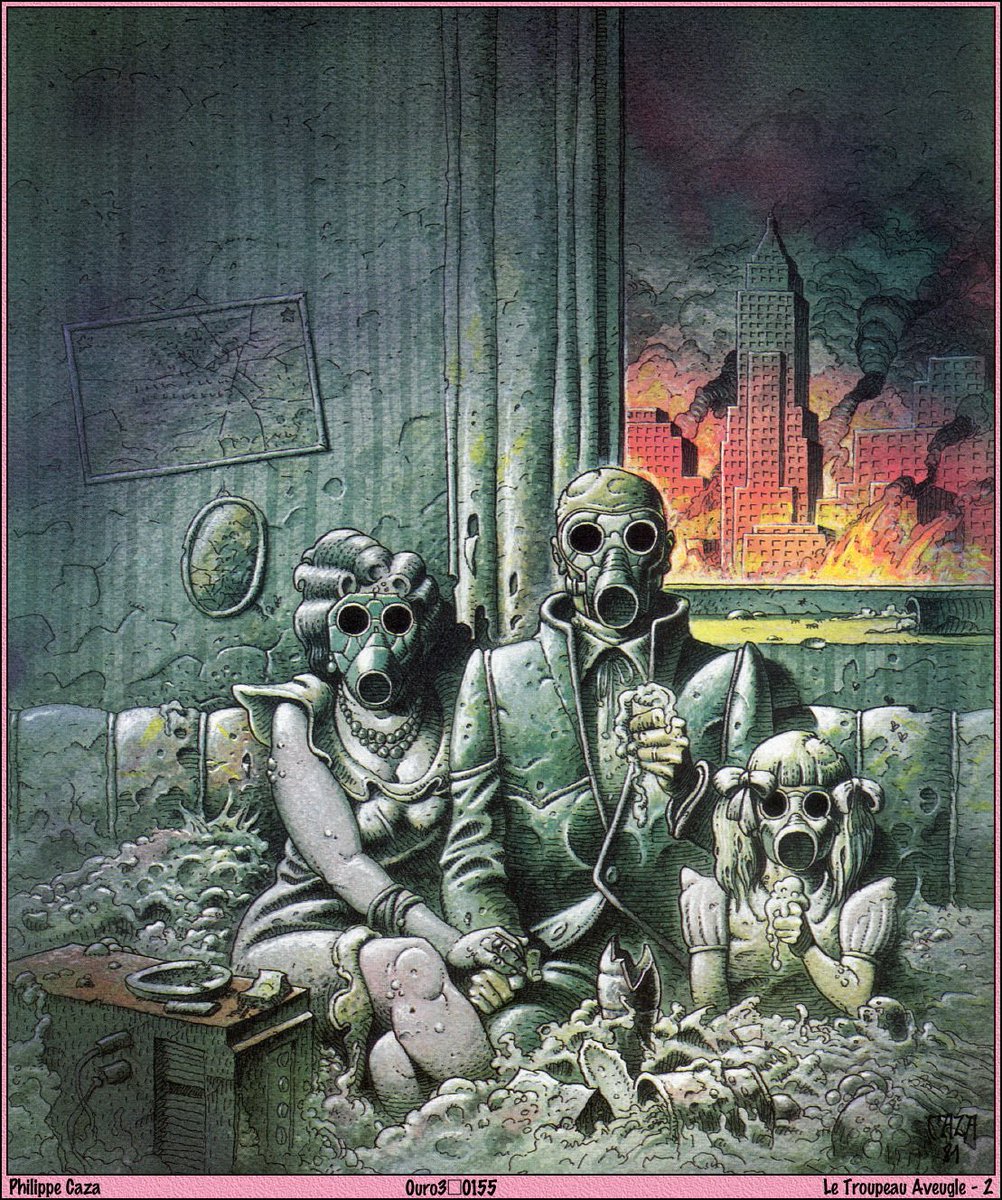

Philippe Caza defined the modern armageddon chic. From his work on Métal Hurlant to his covers for J'ai Lu SF he merged the symbols of modernity with the symbols of disaster.

From #DoctorWho to Dark Ambient you can see the influence of Caza's vision: anonymity, claustrophobia, dispair and the reckless love of a dark future.

Why have we sexualized the apocalypse? Freud noted that sex and death are our two greatest drives, which leak into our desires and must be repressed. Perhaps this is the modern way of surfacing them again.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter