1) Does racism and bigotry increase during economic downturns, and decrease during good times? The belief that racism and economics are deeply connected, and that broad economic solutions can dissolve racism, are at the core of Bernie Sanders’ approach to race.

It’s also wrong.

It’s also wrong.

2) Sanders recently made some waves when, during his interview with the editorial board of the New York Times, he responded in familiar fashion to questions about how Donald Trump came to power. https://twitter.com/nytopinion/status/1217579480652357632

3) That explains the appeal of racism?” he was asked.

“Yeah. People are, in many cases in this country, working longer hours for low wages. You are aware of the fact that in an unprecedented way, life expectancy has actually gone down in America because of diseases of despair...

“Yeah. People are, in many cases in this country, working longer hours for low wages. You are aware of the fact that in an unprecedented way, life expectancy has actually gone down in America because of diseases of despair...

4) "People have lost hope, and they are drinking. They’re doing drugs. They’re committing suicide.”

This was an answer similar to the one I heard Sanders offer to Black Lives Matter protesters at the 2015 Netroots Nation in Phoenix:

This was an answer similar to the one I heard Sanders offer to Black Lives Matter protesters at the 2015 Netroots Nation in Phoenix:

5) “I’ll tell you what we’re going to do. We’re going to transform the economics in America and create millions of decent-paying jobs; we’re going to make public colleges and universities tuition-free; we’re gonna raise the minimum wage to a living wage.

6) “We’re going to transform our trade policy, so that corporate America invests in this country and not low-income countries around the world. “

7) Obviously, this answer fell far short of being satisfactory for people demanding a change in how black people in America are incarcerated, and moreover how readily white people in America treat their lives as utterly disposable and worse. https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2019/11/28/1899814/-The-Red-Summer-100-years-later-The-centennial-Americans-want-to-forget-but-need-to-remember

8) BLM protesters came up onstage to discuss this with Sanders. He stalked offstage after a few minutes, swatting flies as he went. It was immensely disappointing for those of us who backed Sanders, since it demonstrated a failure of understanding he has still not repaired.

9) I have understood for many years that the notion that racial bigotry increases during economic downturns, and declines in economic good times, is not just groundless, but actually contravenes reality. Our present milieu—a robust economy, record hate crimes—is stark evidence.

10) The essential studies in this area revolve around hate crimes, which are the most quantifiable expression of racial, religious, and sexual bigotry available. For years there was a running assumption that these crimes increased during economic downturns. Except they didn’t.

11) No study was able to find any kind of correlation in this regard. However, in the mid-1990s, social scientists were able to find a correlation—a powerful one, as it emerged—between hate crimes and another phenomenon associated with them: demographic shifts.

12) The key study was published in 1998 by Columbia professor Donald Green (then at Yale), titled “From Lynching to Gay-bashing: The Elusive Connection between Economic Conditions and Hate Crime.” https://gspp.berkeley.edu/research/selected-publications/from-lynching-to-gay-bashing-the-elusive-connection-between-economic-condit

13) The conclusion: “The authors speculate that the predictive force of macroeconomic fluctuation is undermined by the rapid rate of decay in the frustration-bred aggressive impulse and the absence of prominent political actors affixing economic blame on target groups.”

14) Subsequent studies by Green and others have concluded that demographic change, especially dramatic shifts within previously homogeneous societies, are more likely to produce the conditions that give rise to hate crimes. Economic downturns have, if anything, a dulling effect.

15) Green told me in a 2003 interview that bias crimes are especially likely to arise when minorities begin moving into communities that were previously homogeneous (i.e., predominantly white, such as Midwestern communities experiencing a large influx of Hispanics).

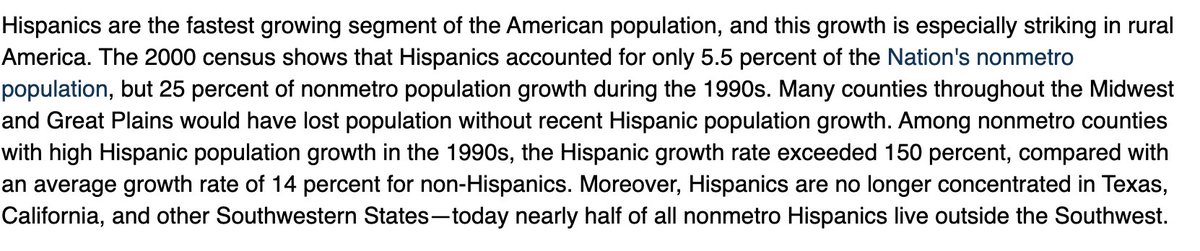

16) This demographic change occurred broadly across rural America between 1995 and 2010, particularly in the Midwest. A 2003 report from the Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Service explained all this in fairly stark numbers:

https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2003/february/hispanics-find-a-home-in-rural-america/

https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2003/february/hispanics-find-a-home-in-rural-america/

17) These kinds of demographic shifts, as noted, often become the primary breeding grounds for hate crimes, even in decidedly non-rural settings. Green also published another study in 1998 on this topic, titled “Defended Neighborhoods, Integration, and Racially Motivated Crime.”

18) Green and his co-authors compared monthly unemployment rates from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics with monthly bias-crime statistics compiled by the New York Police Department for the boroughs of Queens, Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240567589_Defended_Neighborhoods_Integration_and_Racially_Motivated_Crime

19) Jobless rates and bias crimes were examined separately for black, Asian, Latino, gay/lesbian, Jewish, and white victim groups. The study found no statistical link between rates of bias crime and economic fluctuations.

20) “Event count models indicate that crimes directed against Asians, Latinos, and blacks are most frequent in predominantly white areas, particularly those that had experienced an in-migration of minorities. …

21) “No relationship is found between rates of racially motivated crime and macroeconomic conditions, such as the rate of unemployment among non-Hispanic whites; nor does there appear to be an interaction between economic conditions and in-migration of minorities.”

22) Moreover, when they applied the same comparisons to a historical example—analyzing historical statistics that related cotton prices to the lynching of blacks in the South prior to World War II—no such connections were to be found.

23) The study instead found that demographic change in 140 community districts of the city between 1980 and 1990 predicted the incidence of hate crimes. The balance of whites and the target group was an important factor, but the rate at which balance changed was more significant.

24) The most common statistical recipe was an area that was almost purely white in the past which experiences the sudden and noticeable immigration of some other group. In the case of New York, what occurred was a rapid inmigration of three groups: Asians, Latinos and blacks.

25) Blacks were in some ways moved around, or their neighborhood boundaries changed. A number of previously white areas—Bensonhurst being the classic case, or Howard Beach—experienced a rapid inmigration of various nonwhite groups.

26) What was particularly revealing about the hate-crime pattern was that the crimes reflected the targets who were actually moving in; they revealed that this was not a kind of generalized hatred.

27) Bias crime has more of a kind of reality-based component, at least in the aggregate, than is implicated by those psychological theories that suggest that there only exists a generalized sense of intolerance on the part of those who practice extreme forms of bigotry.

28) In a later study, Green found this trend replicated itself elsewhere -- namely, in Germany after the fall of the Iron Curtain in the late 1980s. In that case, there was rapid inmigration of nonwhites into once-homogeneous eastern Germany, followed by a surge in hate crimes.

29) "Thinking about the kind of spatial and temporal dimensions of hate crime is a start in the right direction," says Green. "What it helps to think about is the difference between the static and the dynamic dimensions of this problem.

30) “People talk about the problem of hate crime being hate -- of course, it is a problem, but hate isn't necessarily rising or falling in the society as a whole. What's changing is your proximity to people that you find onerous, and your ability to take action against them.

31) "There are two hypotheses about why it is that hate crimes subside when demographic change runs its course. One hypothesis is that the haters either accept the fact changes occur to them or they move away.

32) “Another hypothesis is that nobody really changes their attitude, it's just that the capacity to organize against some outsider ... no longer becomes possible when one of your back-fence neighbors is now no longer part of the old nostalgic group."

33) As it happens, this very same underlying dynamic was at work in the election of Donald Trump, as I explored in my 2017 book, 'Alt-America: The Rise of the Radical Right in the Age of Trump.' https://www.amazon.com/Alt-America-Rise-Radical-Right-Trump/dp/1786634465/

34) I observed that many political analysts were content to surmise that Trump rode to the presidency on a wave of blue-collar “economic anxiety” resulting from persistent unemployment and lagging wages amid a recovering economy, especially in the swing states.

35) They pointed to Trump’s promises to bring back jobs to those areas as being the primary inducement for blue-collar Democrats to switch tickets. However, this papered over a powerful dimension of the unrest: racial and ethnic demographic shifts that had been occurring there.

36) Well before the election, the Wall Street Journal had reported that Trump was attracting a wave of support from areas where there had been a powerful demographic change in recent years in the form of a large influx of Latino labor. https://www.wsj.com/articles/places-most-unsettled-by-rapid-demographic-change-go-for-donald-trump-1478010940

37) These areas had previously been predominantly homogenous and white, especially in the Midwest and Rust Belt regions, which were simultaneously dealing with gutted local economies and lagging unemployment.

38) Don Leibl, a fifty-one-year-old computer systems analyst, saw the dairy farming hamlet of Arcadia, Wisconsin, where he lived, being transformed from nearly all white to more than one-third Latino as Mexican immigrants streamed in. It was a main reason he was voting for Trump.

39) “If you’d seen the way things have changed in this town, you’d say, ‘Something needs to be done about it,’” Leibl told the WSJ. He and others interviewed by the reporters said Trump’s wall-building pledge and vows to prioritize white workers had struck a chord.

40) The WSJ study relied on a tool often used by social scientists and economists called the diversity index, which measures the likelihood that any two people in a county will differ by race or ethnicity.

41) “In 244 counties, that diversity index at least doubled between 2000 and 2015, and more than half those counties were in the cluster of five Midwestern states.”

42) It noted that even though traditional immigrant gateways in California, Florida, and New York attract far larger numbers of minority immigrants, they have been melting pots for so long that their diversity levels have changed little over the past generation or so.

43) “In 88 percent of the rapidly diversifying counties, Latino population growth was the main driver. In about two-thirds of counties, newcomers helped expand the overall population. In the remaining third, the population fell despite an influx of new arrivals ..."

43) The study found that Trump had won the Republican presidential primaries in these counties by large margins, winning 73% of counties where the diversity index value had risen by at least 100% since 2000, and 80% of counties where the diversity index rose by at least 150%.

44) Support in the primaries for Trump in areas with sharp demographic shifts carried over into the general election: not only did he handily win in most Midwestern states experiencing such shifts, he also eked out slim margins in three key states where they were an issue.

45) What all of these numbers and the studies around them tell us is that economics have relatively little effect on the levels of racism and other bigotry in America.

46) Its underlying cause, in fact, is a pervasive fear among white people that they are losing their positions of demographic privilege, and its accompanying cultural and economic advantages.

46) There are three ways of addressing this fear:

1) By accommodating it, capitulating to it, and encouraging a politics of intolerance that lies when it tells people these fears are well grounded, as Republicans and the conservative movement have done for a very long time ...

1) By accommodating it, capitulating to it, and encouraging a politics of intolerance that lies when it tells people these fears are well grounded, as Republicans and the conservative movement have done for a very long time ...

47) 2) By ignoring it, and assuming that the people experiencing these demographic shifts will eventually “get over it” and adjust their worldviews ...

48) or 3) Recognizing the difficulties that arise around demographic shifts and addressing them proactively, easing refugees and immigrants into formerly all-white communities thoughtfully and helpfully.

50) While the second approach has been the default standard of liberals and leftists for the past three decades, its inadequacies have been laid bare by the rise of Trump. Similarly, any approach such as Sanders’ will innately be inadequate to this moment in our racial history.

51) Mind you, pointing this out is not necessarily a competitive slight for Sanders; no presidential candidate yet has ever approached or discussed the third option, largely because the role of demographics has been so generally overlooked.

52) Probably the one candidate who has come closest to examining the toxic effects of white demographic fear is Elizabeth Warren, who acknowledged that racism is the driver in mass incarceration of black people in discussing her plans to confront it. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/04/23/warren-there-is-no-criminal-justice-reform-without-addressing-racism/

53) However, all the Democratic candidates—Sanders only being the most prominent example, and hardly alone in this—need to discard, once and for all, the harmful myth that racism can be ended through the simple nostrum of economic well-being.

54) Racism operates in an entirely different sphere: In the underbelly of so much American mythology about who we are and what we have done to create the world we live in today. It loves to tell white Americans they are always the good guys. It hates facing the truth.

55) And it hates change, especially when the change is not one that obviously advantages them. It responds to change with fear, which the mythology supports (think of Trump’s favorite campaign-trail anecdote, about the viper who bites his savior). And with fear comes violence.

56) The reality, of course, is much more complicated than the mythology. If Democrats wish to craft policies that are genuinely effective around facts and logic rather than feel-good half-measures, they will find ways to embrace that reality, instead of inventing false ones.

@threadreaderapp Unroll please.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter