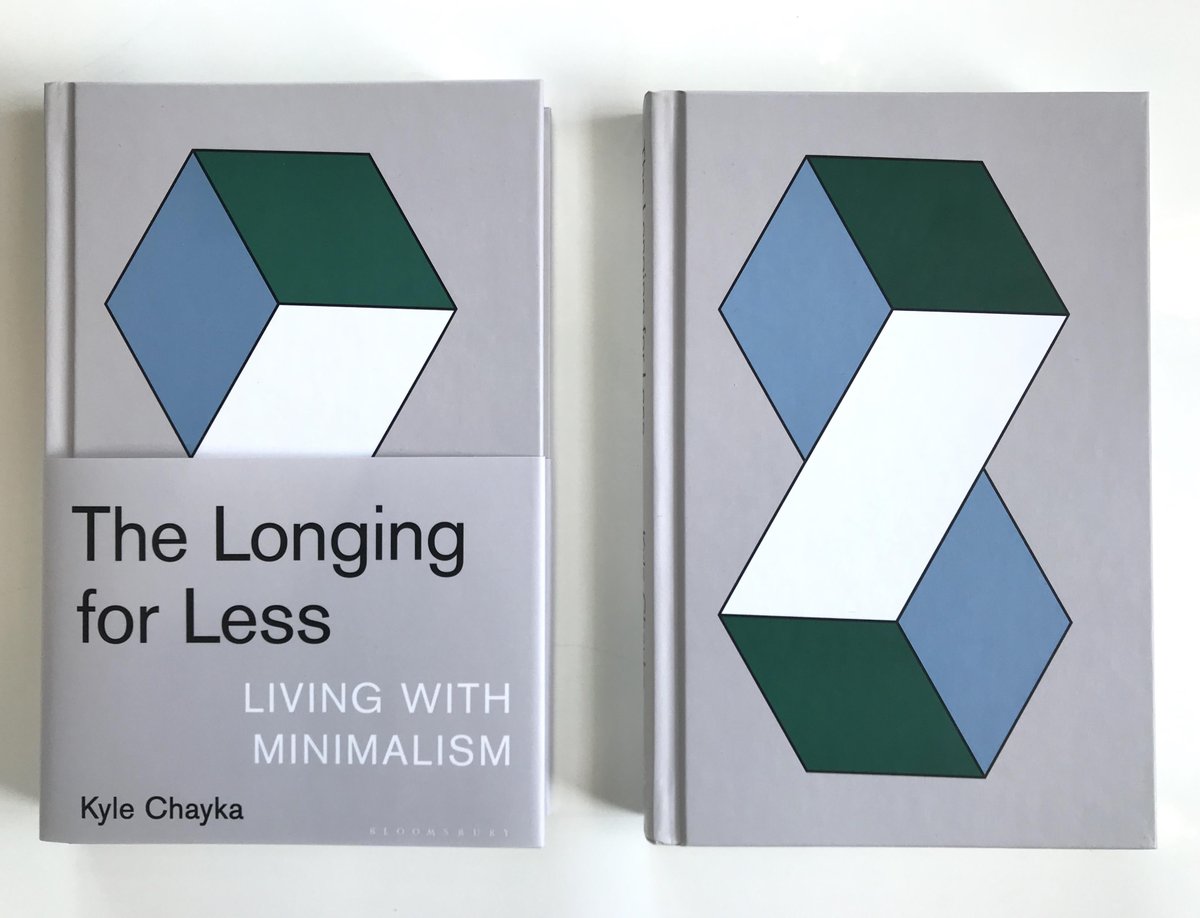

My first book, The Longing for Less: Living with Minimalism is on shelves today from @bloomsburypub! You can order it here: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/the-longing-for-less-9781635572100/ But I also wanted to do a thread of my favorite people & quotes from the book —

The book is about deconstructing the trendy minimalism of Instagram, Marie Kondo, etc, and getting back to more fundamental ideas that aren’t just about austere decorating and consuming less. Here are some of those figures:

Together, they present a more expansive idea of minimalism & living simply. Like the Stoic Marcus Aurelius, c. 2nd century CE: “That which is really beautiful has no need of anything.”

Marx was kind of a minimalist, arguing that buying so much stuff was just a balm for the alienation of capitalism: “The less you are, the less you express your own life, the more you have”

The American philosopher Richard Gregg called for “voluntary simplicity” in the 1920s. He presaged internet critiques:

“We think that our machinery and technology will save us time and give us more leisure, but really they make life more crowded and hurried”

“We think that our machinery and technology will save us time and give us more leisure, but really they make life more crowded and hurried”

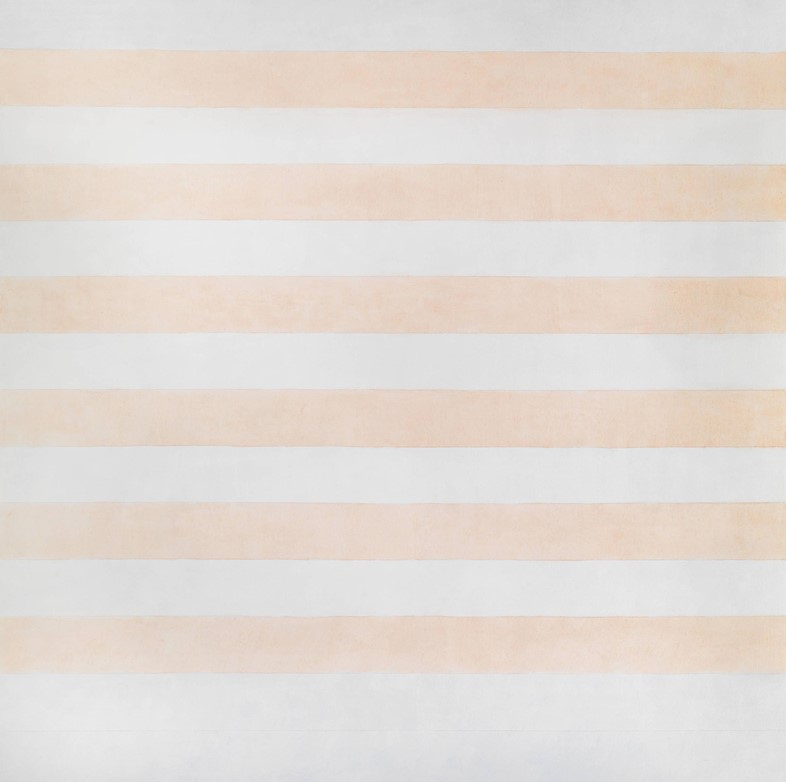

Agnes Martin is one of the best-known minimalist artists. She used simplicity to evoke universal feelings:

“We are in the midst of reality responding with joy. It is an absolutely satisfying experience but extremely elusive.”

“We are in the midst of reality responding with joy. It is an absolutely satisfying experience but extremely elusive.”

Minimalism sometimes puts elegance and control above all:

“You can feel comfortable in any environment that's beautiful,” said the architect Philip Johnson of his 1949 Glass House, which helped popularized the modernist aesthetic in America

“You can feel comfortable in any environment that's beautiful,” said the architect Philip Johnson of his 1949 Glass House, which helped popularized the modernist aesthetic in America

After architectural modernism, Minimalist art in '60s New York embraced pre-made industrial materials and geometric forms.

Its simplicity was a radical departure from art history. “What you see is what you see,” as the painter Frank Stella said.

Its simplicity was a radical departure from art history. “What you see is what you see,” as the painter Frank Stella said.

Minimalism emptied art out of figures, emotions, and narrative. The artist Donald Judd even hated the word itself: “There isn’t any such thing as minimalism,” he wrote in 1981.

Minimalism is always associated with emptiness, but Judd’s homes were crowded with collections of books, art, and artifacts. They only look minimalist because he had such an excess of space to fill, like in his Marfa library:

(If I could live anywhere it would absolutely be an aircraft hanger that Judd turned into a home studio)

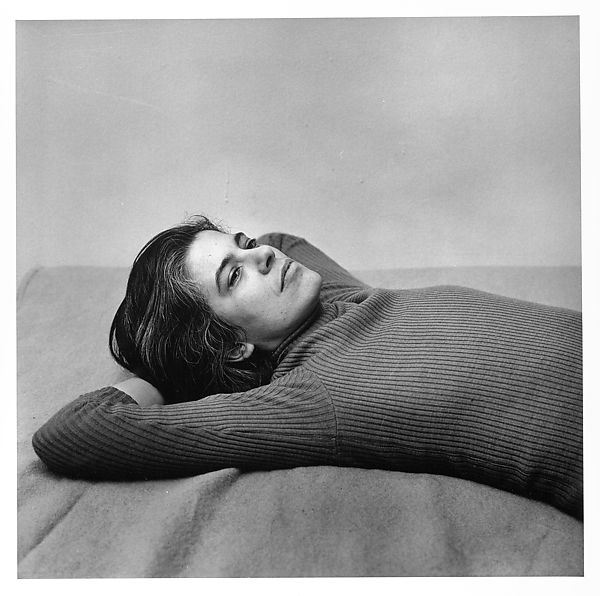

Minimalism can ultimately mean more rather than less, as Susan Sontag wrote in 1967:

“There is no talented and rigorous asceticism that doesn’t produce a gain (rather than a loss) in the capacity for pleasure”

“There is no talented and rigorous asceticism that doesn’t produce a gain (rather than a loss) in the capacity for pleasure”

Minimalism can be about sensory perception, too, the way we feel overwhelmed with our environment and crave controllable stimuli instead of the chaotic world…

The composer Erik Satie pioneered the idea of music you don’t have to pay attention to back in 1920. He told the listeners of his “Furniture Music” compositions to “behave… as if it did not exist”

Satie’s idea was echoed by Brian Eno in 1978: His ambient music “must be as ignorable as it is interesting.” I love Eno’s “Music for Airports”

(Eno actually came up with the idea for ambient music when he got hit by a car and was stuck in bed with a record of harp music playing at too low a volume — it became part of his surroundings rather than a self-contained experience)

But minimalism can be challenging, not just comforting or relaxing, as in the work of the late queer, Black minimalist composer Julius Eastman. My favorite piece of his is “Stay On It”: https://vimeo.com/147239206

Ultimately, minimalism helps us not to barricade our senses with pleasant sounds or sensation but rethink what music is, as in John Cage’s “Water Walk”

The last chapter of my book is about the Japanese aesthetics of nothingness.

The 13th-century Zen monk Mumon said nothingness was not pure absence, but “a red-hot iron ball which you have gulped down and which you try to vomit up, but cannot.”

The 13th-century Zen monk Mumon said nothingness was not pure absence, but “a red-hot iron ball which you have gulped down and which you try to vomit up, but cannot.”

We can appreciate absence.

As the novelist Junichiro Tanizaki put it in his essay “In Praise of Shadows”: “We find beauty not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another creates.”

As the novelist Junichiro Tanizaki put it in his essay “In Praise of Shadows”: “We find beauty not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another creates.”

One of my favorite figures in the book is Kuki Shuzo, a Japanese philosopher who studied in Paris & Germany in the 1920s, moving between cultures and embracing a deep ambiguity. As he wrote in a poem:

“This is a life

That misses its way”

“This is a life

That misses its way”

Kuki’s work on the Japanese quality of “iki” describes what deeper minimalism could be:

“an attitude of disinterestedness toward fate, free from all attachments, an attitude that has its source in an awareness of fate”

“an attitude of disinterestedness toward fate, free from all attachments, an attitude that has its source in an awareness of fate”

At the end of the book, Japanese rock gardens are an icon and a meeting point for global minimalism: an enduring form of absence amidst the bustle of life and time.

At Ryoan-Ji in Kyoto, only 14 of the 15 garden stones are visible at any one time — the effect is in the spaces between the stones, the absence that is always present, that we have to dwell in.

If any of these people or ideas in the expanded field of minimalism seem interesting, please do buy the book and learn more:

Bloomsbury: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/the-longing-for-less-9781635572100/

Indiebound: https://www.indiebound.org/book/9781635572100

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Longing-Less-Living-Minimalism/dp/163557210X/

Bloomsbury: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/the-longing-for-less-9781635572100/

Indiebound: https://www.indiebound.org/book/9781635572100

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Longing-Less-Living-Minimalism/dp/163557210X/

The book doesn’t provide an answer or a solution to minimalism, because there isn’t one. Minimalism is a way of asking questions.

I’ll be happy if the book is like a mixtape: find some cool ideas, artists, and writers, then pursue them to find your own answers

I’ll be happy if the book is like a mixtape: find some cool ideas, artists, and writers, then pursue them to find your own answers

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter