Wandering down a rabbit-hole of animal sleep this morning

One of the fundamental things about sleep is that, almost without exception, it’s a universal feature of complex living organisms

One of the fundamental things about sleep is that, almost without exception, it’s a universal feature of complex living organisms

That in itself tells us something important about sleep: we are vulnerable when we sleep so, if it weren’t essential, we’d expect to see at least some species who don’t sleep

But ... everyone (pretty much) sleeps and, when living things don’t get it, there are consequences

But ... everyone (pretty much) sleeps and, when living things don’t get it, there are consequences

Even in the most ancient of life-forms, primitive unicellular organisms, while perceiving ‘sleep’ itself isn’t exactly easy, we can see circadian variations ... even the most basic of life listens to the tick/tock of its internal clock

We had a bee hive outside our sleep lab last summer, which prompted me to do a bit of reading about sleep in bees

(here’s a couple grabbing a quick snooze in a flower

)

)

(here’s a couple grabbing a quick snooze in a flower

)

)

Bees sleep for 5-8 hours, usually at night

Why?

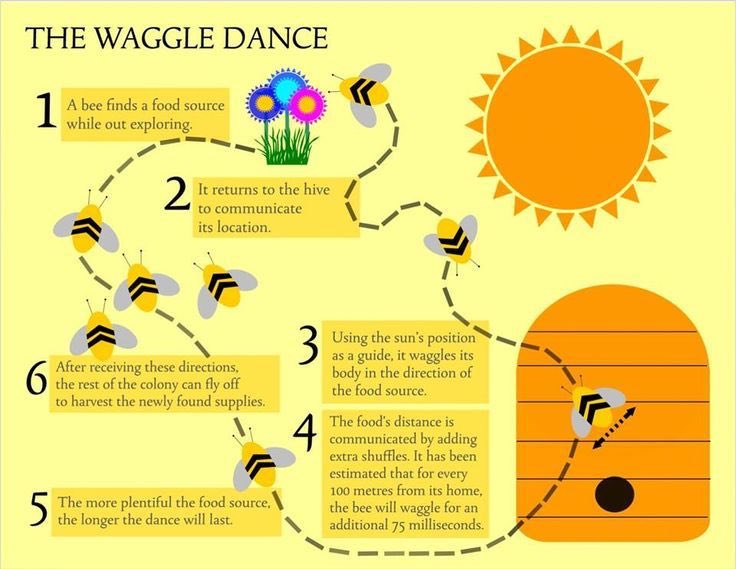

Well, for bees, sleep helps them perform the waggle dances they use to communicate where pollen sources are to the hive

If they don’t sleep ... they dance more badly

(whether the same is true of humans hasn’t been studied )

)

Why?

Well, for bees, sleep helps them perform the waggle dances they use to communicate where pollen sources are to the hive

If they don’t sleep ... they dance more badly

(whether the same is true of humans hasn’t been studied

)

)

Sleepy bees are also less good at navigating in general - if they haven’t had a decent night’s sleep, they will make more mistakes when trying to navigate back to their hive

(Another reason why power-napping on longer drives might be sensible?)

(Another reason why power-napping on longer drives might be sensible?)

Bee scientists (cool job!) have also been able to demonstrate that, just like in humans, sleep helps bees process memories ... again, probably important for remembering where that great new pollen source was

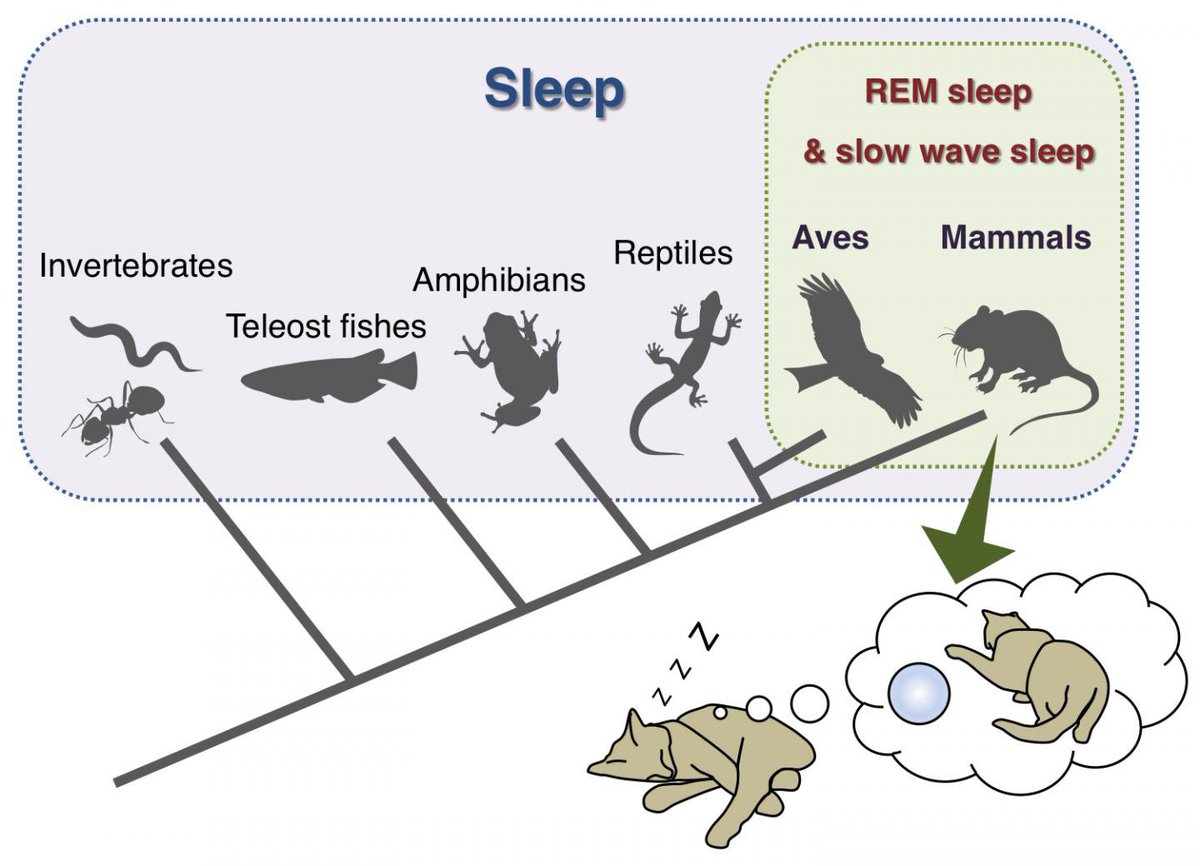

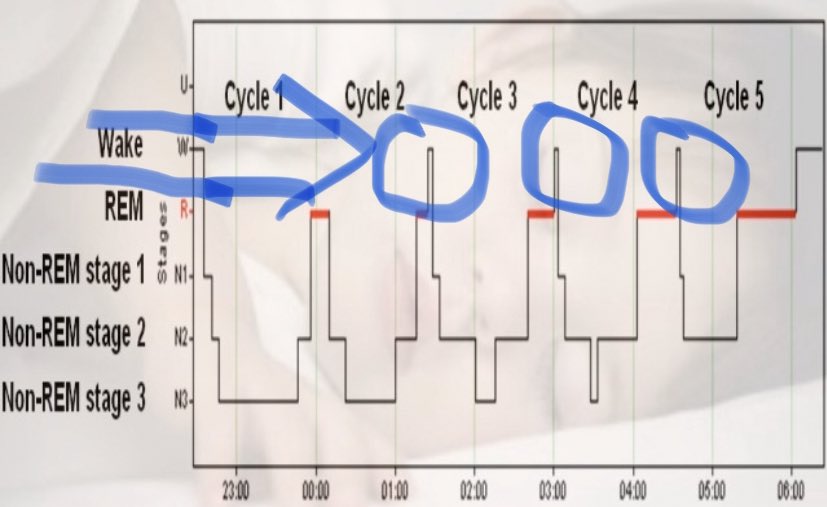

Across bird and mammal species, there is a relative consistency of features of sleep

Animal sleep scientists can demonstrate the classic distribution of REM and non-REM sleep we see in humans (it’s much harder to prove presence/absence of these in evolutionarily older species)

Animal sleep scientists can demonstrate the classic distribution of REM and non-REM sleep we see in humans (it’s much harder to prove presence/absence of these in evolutionarily older species)

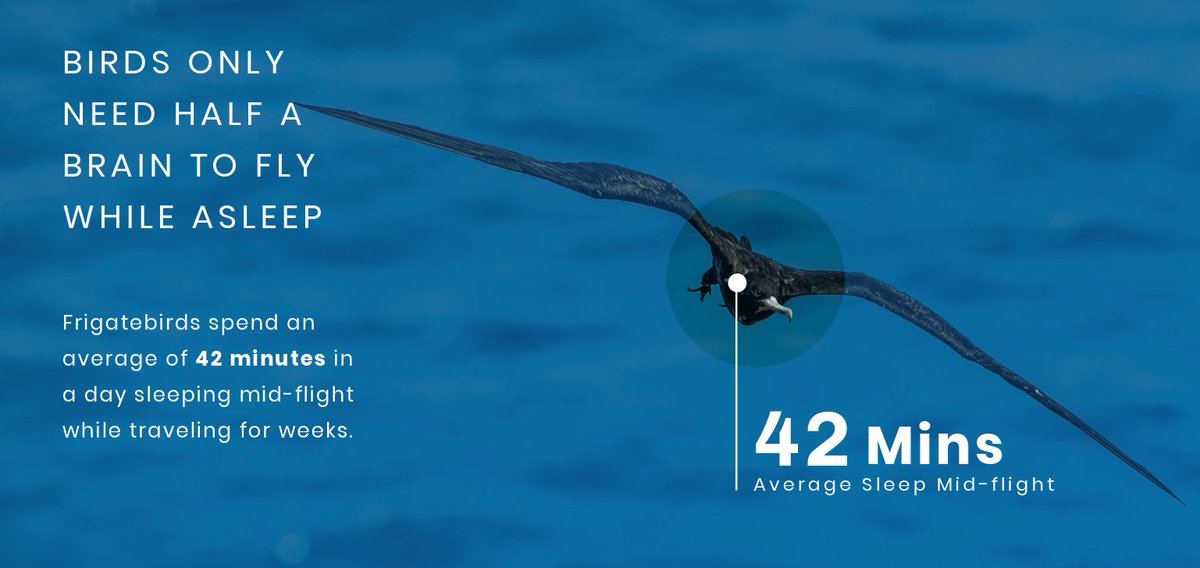

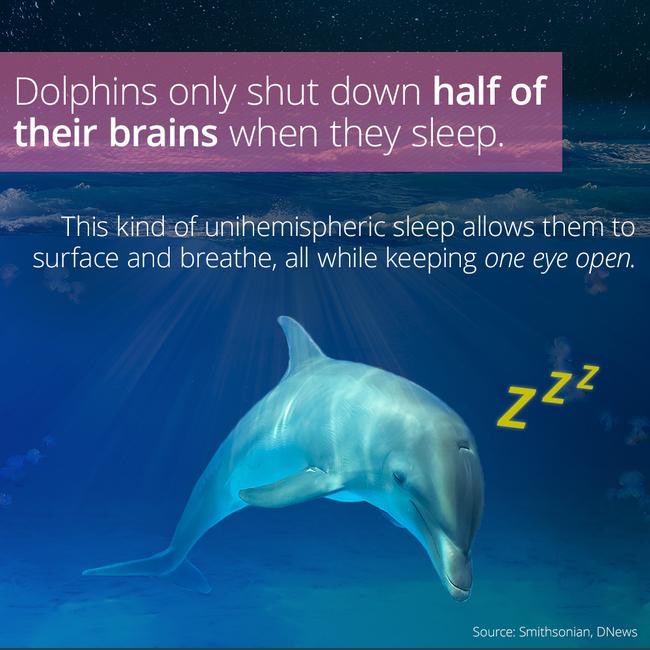

Birds, and aquatic mammals like dolphins, have a special sleep trick: they can let one half of their brain sleep at a time

This allows them to sleep while flying - with one eye open and one eye shut!

(I *may* be able to do this in some meetings... )

)

This allows them to sleep while flying - with one eye open and one eye shut!

(I *may* be able to do this in some meetings...

)

)

Many species have evolved sleep habits to protect themselves from predators

The natural arousals from sleep at the end of each sleep cycle probably serve this evolutionary purpose - the brain checking just to make sure that the surrounding environment is still safe

The natural arousals from sleep at the end of each sleep cycle probably serve this evolutionary purpose - the brain checking just to make sure that the surrounding environment is still safe

Birds who sleep in more vulnerable environments tend to sleep less in general than those where they are less vulnerable to predators.

In flocks - or ducks sleeping in a row - those on the outside tend to sleep less deeply than those in the middle, to help protect the group as a whole

Species evolve to sleep by day or night

Although we see a flipping of rhythms like body temperature, activity and hormone secretion in nocturnal animals, activity in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (our central body clock) remains similar in nocturnal and diurnal animals

Although we see a flipping of rhythms like body temperature, activity and hormone secretion in nocturnal animals, activity in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (our central body clock) remains similar in nocturnal and diurnal animals

Melatonin often referred to as “the sleep hormone”

More correctly, it’s “the darkness hormone”

In diurnal species, like humans, rising melatonin levels support sleep onset

In nocturnal animals, physiology responds the opposite way: rising melatonin supports increased activity

More correctly, it’s “the darkness hormone”

In diurnal species, like humans, rising melatonin levels support sleep onset

In nocturnal animals, physiology responds the opposite way: rising melatonin supports increased activity

Different species spend different proportions of their lives asleep

Some bat species are at the upper end - spending 20hrs/day, over 80% of their lives asleep!

Some bat species are at the upper end - spending 20hrs/day, over 80% of their lives asleep!

At the other end of the spectrum, giraffes - who can be very vulnerable to prey when they sleep (takes time to stand up and run!) and need to forage for food - sleep for less than 2 hours/day, only 8% of their lives

Humans are towards the lower end of the spectrum - we spend about a third of our lives asleep

That varies across the lifespan as well though - newborns spend 2/3 of their lives asleep, and older adults may only spend a fifth or so of their time asleep

That varies across the lifespan as well though - newborns spend 2/3 of their lives asleep, and older adults may only spend a fifth or so of their time asleep

As a very general rule, the smaller the species, the more time they are likely to spend asleep (though it’s not as simple as that!)

Herbivores also tend to sleep less (and spend more time awake foraging for food)

Elephants are another short-sleeping species, around 2 hrs/day

Herbivores also tend to sleep less (and spend more time awake foraging for food)

Elephants are another short-sleeping species, around 2 hrs/day

Animals like horses and giraffes can catch some sleep standing up, often in short power naps of only 5-15 minutes (for longer deeper sleep they tend to lie down)

(Horses have funky anatomy that allows them to doze while standing with minimal muscle exertion)

(Horses have funky anatomy that allows them to doze while standing with minimal muscle exertion)

Otters are another species who have evolved protective behaviours to keep them safe while they sleep ... sleeping otters hold hands

Dolphins, like some birds, sleep with one half of their brain at a time, making sure they stay alert for predators (and remember to come up for air from time to time)

They alternate the sleeping brain hemisphere every couple of hours or so

They alternate the sleeping brain hemisphere every couple of hours or so

Many mammals sleep in multiple bursts of sleep through a 24 hour period - polyphasic sleep

Most primate species, like us, tend to sleep in one predominantly consolidated sleep period at night - uniphasic sleep

(though even that can vary in humans)

Most primate species, like us, tend to sleep in one predominantly consolidated sleep period at night - uniphasic sleep

(though even that can vary in humans)

Although sleep is seen in all animal species, some can go to extremes humans would find punishing

Seals can go for weeks without any REM (dream) sleep while at sea - and switch between sleeping with half a brain at sea, and their whole brain when sleeping on land

Seals can go for weeks without any REM (dream) sleep while at sea - and switch between sleeping with half a brain at sea, and their whole brain when sleeping on land

These differences in how different animal species sleep give us insights into what the different types of sleep are for - we’ve still got lots to learn!

And, seeing as we’re down a rabbit-hole, how do rabbits sleep?

Well, they tend to sleep both in the day AND at night, getting around 12 hours sleep in total - and are most active around dawn and dusk, which lets us describe them as crepuscular! (brilliant word)

Well, they tend to sleep both in the day AND at night, getting around 12 hours sleep in total - and are most active around dawn and dusk, which lets us describe them as crepuscular! (brilliant word)

Some things look like sleep, but aren’t

(The classic medical example of this is anaesthesia ... no matter what the anaesthetists mutter as they “just pop you off to sleep for your operation”, general anaesthesia is very different physiologically to sleep itself)

(The classic medical example of this is anaesthesia ... no matter what the anaesthetists mutter as they “just pop you off to sleep for your operation”, general anaesthesia is very different physiologically to sleep itself)

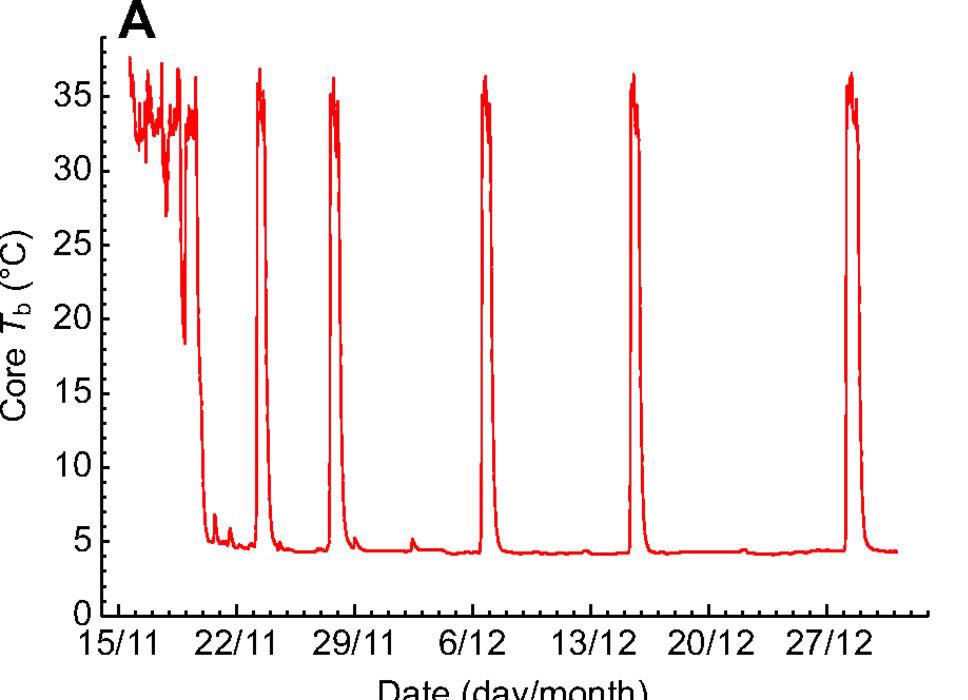

Some animals are able to profoundly alter their physiology to survive during extremes of weather: hibernation

In hibernation, core body temperature and heart rate drop significantly, far more than in normal sleep, and metabolism slows, dramatically deceasing energy expenditure

In hibernation, core body temperature and heart rate drop significantly, far more than in normal sleep, and metabolism slows, dramatically deceasing energy expenditure

The drop in heart rate can be profound: chipmunks drop their heart rate from 200bpm to just 5!

Breathing also slows right down ... and in some animals, can stop altogether!

Breathing also slows right down ... and in some animals, can stop altogether!

Some animals have extra tricks here: frogs retain high levels of glucose in their bloodstream, acting as natural anti-freeze, to allow them to survive even colder temperatures

Hibernation physiology is fascinating, a complete change in how the animal normally functions, with energy and water drawn from fat supplies

Body temp is allowed to drop to a set-point, basically the point below which it would take too much energy to successfully re-warm from

Body temp is allowed to drop to a set-point, basically the point below which it would take too much energy to successfully re-warm from

Sleep is a relatively easy state to reverse; even from deep sleep, animals, including us, can usually rouse in a matter of minutes at most

Hibernation can take much longer to come around from, as body systems slowly come back to normal levels of functioning

Hibernation can take much longer to come around from, as body systems slowly come back to normal levels of functioning

A hibernation quirk: brain activity can still more closely resemble wake than sleep, so when some animals ‘wake’ from hibernation, they need to spend time catching up on *actual* sleep their brains have missed while they hibernated

... another reason roused bears might be grumpy

... another reason roused bears might be grumpy

Hibernation can be regulated by a number of factors: food supplies, environmental temperature, day length - which means hibernation length can vary from year to year and, for some, is likely to be affected by climate change

Most animals hibernate for weeks or months but some can enter hibernation-like states (torpor) on a daily basis

For animals with high-metabolic demands, like the hummingbird, this allows them to survive on a daily basis

For animals with high-metabolic demands, like the hummingbird, this allows them to survive on a daily basis

Can humans hibernate?

No - but some scientists think it *might* be possible.

There are a few tantalising physiological hints, not least the occasionally miraculous human ability to survive at extreme cold temperatures https://www.bbc.com/news/amp/uk-50681489

No - but some scientists think it *might* be possible.

There are a few tantalising physiological hints, not least the occasionally miraculous human ability to survive at extreme cold temperatures https://www.bbc.com/news/amp/uk-50681489

The rare, poorly understood, sleep disorder Kleine-Levin Syndrome - characterised by profound, difficult to rouse from, somnolence - is sometimes colloquially referred to as a “hibernation syndrome”

There are key differences in KLS to true hibernation though

There are key differences in KLS to true hibernation though

KLS’ other common (and unhelpful!) name in the media in particular is the “Sleeping Beauty Syndrome” ... capturing that idea that in humans, ‘hibernation’ is more commonly found in the realms of magic or fantasy ...

... and human hibernation also found in science fiction: will future deep space exploration have crews who spend much of their travel time in deep freeze, hibernating between the stars?

Who knows?

As with sleep though, understanding animal hibernation better may help us too

Who knows?

As with sleep though, understanding animal hibernation better may help us too

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter