I have read @JesseJenkins's piece, @JulianSpector's write up of it. Having nerded out on this topic for several years now I just can't let this one go both b/c I find it fascinating and b/c I think Jesse & co. are falling into a trap of only looking @ short run values. (1 of ?)

a typical dist solar system will be online for 30+ years. It will come as we (hopefully) decarbonize much of the economy by electrifying it. As we do that it will be important to ensure we avoid this growth from driving up peak loads and thereby infrastructure investment.(2 of ?)

If we only look at short run values-- the avoidance of line losses, the avoidance of transmission congestion, the ability to avoid a specific distribution system upgrade we are massively undervaluing DERs (3 of ?)

To make this conversation relatively simple, let's focus on the distribution system though it applies to the transmission and generation system as well. And to keep it concrete, let's focus on California's experience with energy efficiency. (4 of ?)

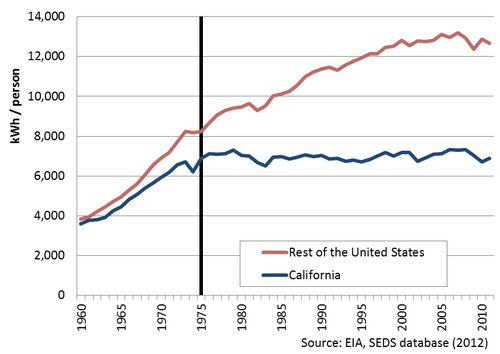

The Rosenfeld Curve is named after Art Rosenfeld, basically the father of energy efficiency in the US. He demonstrated how California flattened out the electricity demand growth in California after the 1970s, even as the economy took off. (5 of ?)

If the all of that energy efficiency hadn’t been done, there would be a lot more load growth like there was in the rest of the United States and therefore a lot more investment in distribution substations, transmission lines, and powerplants. (6 of ?)

The value of that energy efficiency was the ability to avoid utilities from ever having to consider new substations, lines, etc that they otherwise would have needed should growth had gone on unabated like it did in the rest of the US. (7 of ?)

This didn't mean the utilities in California didn't need to do upgrades. Instead, when the utility engineers went to do their annual plans of what needed to be built there were less projects showing up in those plans than there otherwise would have been. (8 of ?)

The chief value of all that EE was avoiding peak load growth and thereby avoiding the utilities from having to even consider many projects that otherwise would be needed. The projects avoided were those the utilities never knew they would have otherwise needed (9 of?)

The MIT approach basically says,“well, if there isn’t a distribution system need you can avoid in the location where you are, then you don’t have value”. I call this the “right place, right time... your mother is a saint” standard based on a “Four Rs” standard from SDG&E (10 of ?

This Four Rs standard basically set a high bar for whether DERs could act as a non wires alternative based on whether they can come on line and perform in a certain set of hours to avoid a SPECIFIC PROJECT in the utilities distribution system plans. (11 of ?)

There is a fair debate over the performance requirements, timing of deployment, etc. for for whether a utility should contract with a DER or set of DERs to avoid a PLANNED upgrade. But that is not "THE" value of DERs. (12 of ?)

As the MIT paper notes, there was a study done by UC Berkeley a few years back that showed that only 10% of the distribution system had planned projects that could be avoided by distributed solar. (13 of ?)

This may be true (sounds probable in a flat load growth world we're in), but again, it is conflating short run value (can you avoid THIS planned project) with long run value (can you avoid peak load growth over the life of your project) (14 of ?)

An easy way to think about this difference between planned upgrades and the long run value of DERs is to think about this: would there only be upgrades needed on 10% of the distribution grid had California not done all of its efficiency policies? (15 of ?)

Or think about this: how much efficiency would we have done if each lightbulb swap out or A/C unit upgrade needed to be evaluated based on the ability avoid the local substation needing an upgrade in the next 5 to 7 years (16 of ?)

…probably we wouldn’t have done a lot of EE and we would have built a lot more utility infrastructure. (17 of ?)

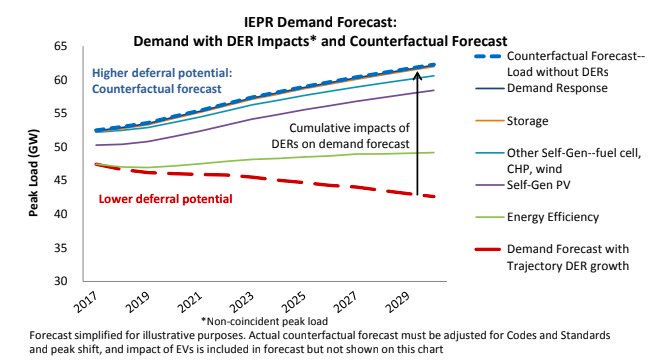

The @californiapuc recently put out a great graph as they analyze implementation of one of their decisions from a couple years ago where they recognized that they need a long-run locational value in addition to a shorter run deferral value. (18 of ?)

In this @californiapuc graph the red line is how many upgrades are needed with the current DERs on the grid- not a lot b/c the load forecast INCLUDEs the DERs. Take the DERs out and you see how much more the utilities would need to invest (the blue dashed line). (19 of ?)

So what is the point of this academic debate? Beyond the fact that I find it fascinating, there are policy debates about BTM vs. utility scale resources which is related to a debate more salient to me: what comes after net metering? (20 of ?)

There is an appropriate discussion about what comes next and we need to be having that conversation. But obsessing over whether you’re on the right feeder to avoid a planned upgrade is really missing the point. (21 of ?)

What will be more important that location is TIME— does the distribution system peak 4 to 9 June to August IS a WAY more important question than “does this specific feeder need an upgrade” particularly since the upgrade needs cascade up to sub-Trans, Trans, Gen. (22 of ?)

We can move to something not NEM that pays for those higher value hours rather than based on rates and rate design, but also not be setting a standard that basically ignores the majority of a DER’s value, which is preventing many needs from ever entering utility plans (23 of ?)

As an aside, that tariff should also be a great battery arbitrage rate (“sick nasty" is the technical adjective) as it gets away from all the averaging you see in rate design (24 of ?)

This is already the direction VDER is going, establising a 460 hour window where your "injections" into the grid get value for avoiding distribution capacity just like they have for gen capacity. And you're welcome for that solar developers, btw... (25 of ?)

Finally, the whole reliability argument is one where the DER community should be pushing WAY harder. The MIT paper says that avoiding the cost of an outage with a personal battery or other backup is a private benefit, which is true (26 of ?)

...if I use my battery to watch TV during an outage it is not like anyone gets that benefit besides little ol' me. HOWEVER, utilities use my and others' personal cost of an outage and add up those costs to justify their reliability investments as being cost effective. (27 of ?)

The utilities then get the commissions to approve those grid mod expenses to reduce outages and we ALL pay for them, even though many of us won’t get the benefit of the investments (particularly those of us who have our own back up). (28 of ?)

Customer batteries and microgrids can provide customers value that the utilities would have otherwise ascribed to their more old fashion ways of improving reliability (e.g., automated switches, fault indicators, etc.) avoiding the need for them to make the investments (29 of 30)

...alright, that is it for now, but there is so much more to talk about here. But first things first-- if we only look at short run value for DERs, DERs are going to be "not cost effective". Duh. So let's take a more accurate long run view (30 of 30).

...and thank you to @JesseJenkins and his team for writing this. As much as I find fault in some of the assumptions it is a conversation worth having and one I hope we can engage in via #energytwitter and hopefully in person at some point

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter