#OnThisDay in 1803 in Dublin, the United Irishmen rose up against British rule. The rebellion didn’t last very long and mostly became a footnote in Irish history. Today I’m going to try and rehabilitate it.  Thread

Thread  #history #ireland #LocalHistory #twitterstorians #oralhistory

#history #ireland #LocalHistory #twitterstorians #oralhistory

Thread

Thread  #history #ireland #LocalHistory #twitterstorians #oralhistory

#history #ireland #LocalHistory #twitterstorians #oralhistory

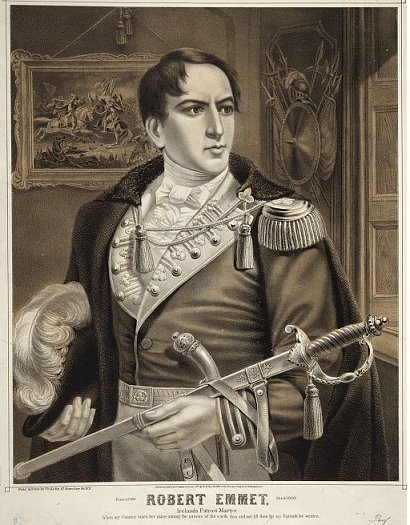

The 1803 Rising is primarily known for the brutal execution of its leader Robert Emmet and, particularly the speech he made from the dock – a heavily mythologized figure at this point. But this does it (and him, ironically) a grave disservice.

Also, the 20+ men hung on Thomas Street and elsewhere in the weeks leading up to the famous death of Robert Emmet have been almost completely forgotten. (More on them later.)

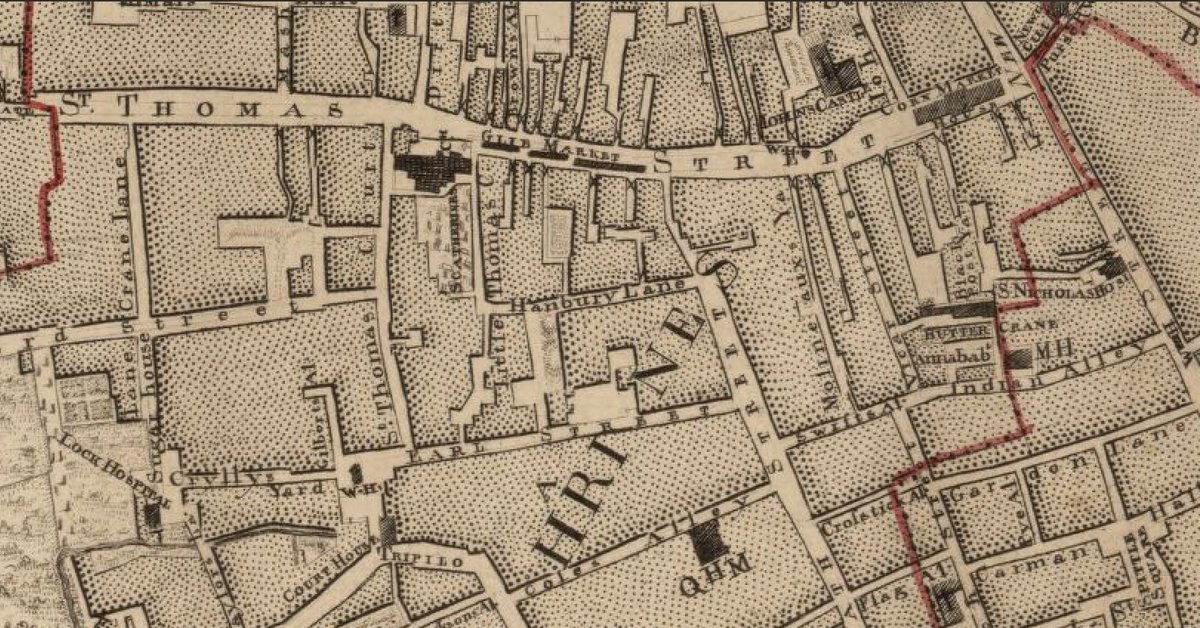

The rebellion kicked off on Thomas Street, a working-class area of Dublin with a fascinating history, roughly halfway in-between the cathedral of Christchurch - just west of Dublin Castle, overlooking the River Liffey - and the giant Guinness factory at St. James Gate.

Dublin Castle itself was the primary target of the United Irishmen, the seat of British power in Ireland and not very well defended. Dublin was surrounded by several British barracks which could easily provide reinforcements, but these were to be targeted separately.

And then once Dublin Castle fell, the rest of the country was to join the rebellion, safe in the knowledge that any British response would be paralyzed by their administration in Ireland being in complete disarray.

(Warning: I am not a historian. Follow the excellent people at #twitterstorians for the real deal. I have read some excellent ones on this very topic, which I'll share in due course!)

British power was very centralized and communications were slow (no wifi, yo), so by the time London would have heard about a Dublin rebellion and organized a retaliatory force, the United Irishmen would have been in complete control. At least that was the plan.

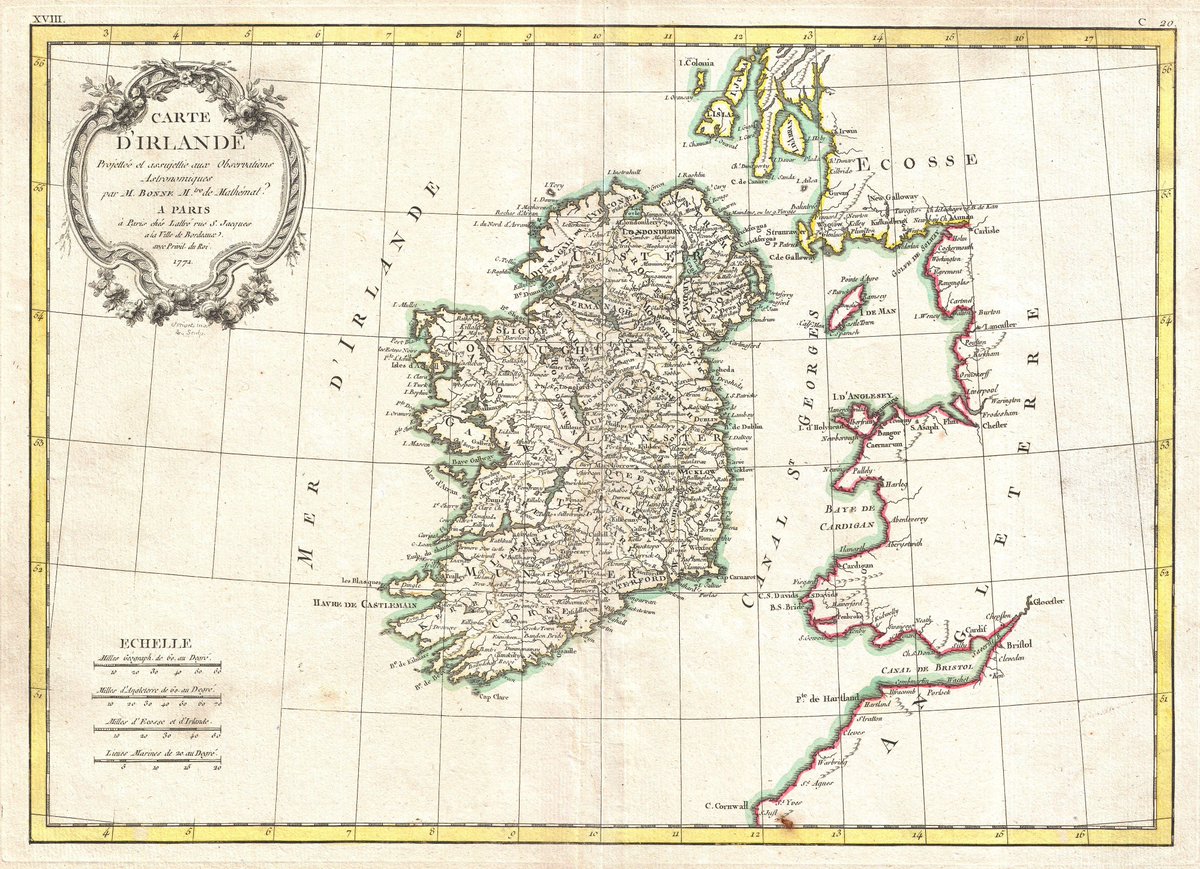

The hope was to also attract a French invasion fleet. Robert Emmet had been part of a secret diplomatic delegation for some time in Paris along with other exiled republicans, lobbying Napoleon’s administration for military assistance against their common enemy: the British crown.

This wasn’t the vain hope it is sometimes portrayed as. After the collapse of the Peace of Amiens in May 1803, the likelihood of a renewed French invasion of Ireland soared. (Britain had declared war on France in response to Napoleon seizing Switzerland.)

But why didn’t the United Irishmen plan for the whole country rise up at the same time? Good question! Two reasons, both related.

First, a widescale rebellion had just occurred in 1798 which was brutally put down by the English resulting in up to 50,000 Irish deaths. A number of high profile atrocities were committed which terrorized the population of Leinster in particular.

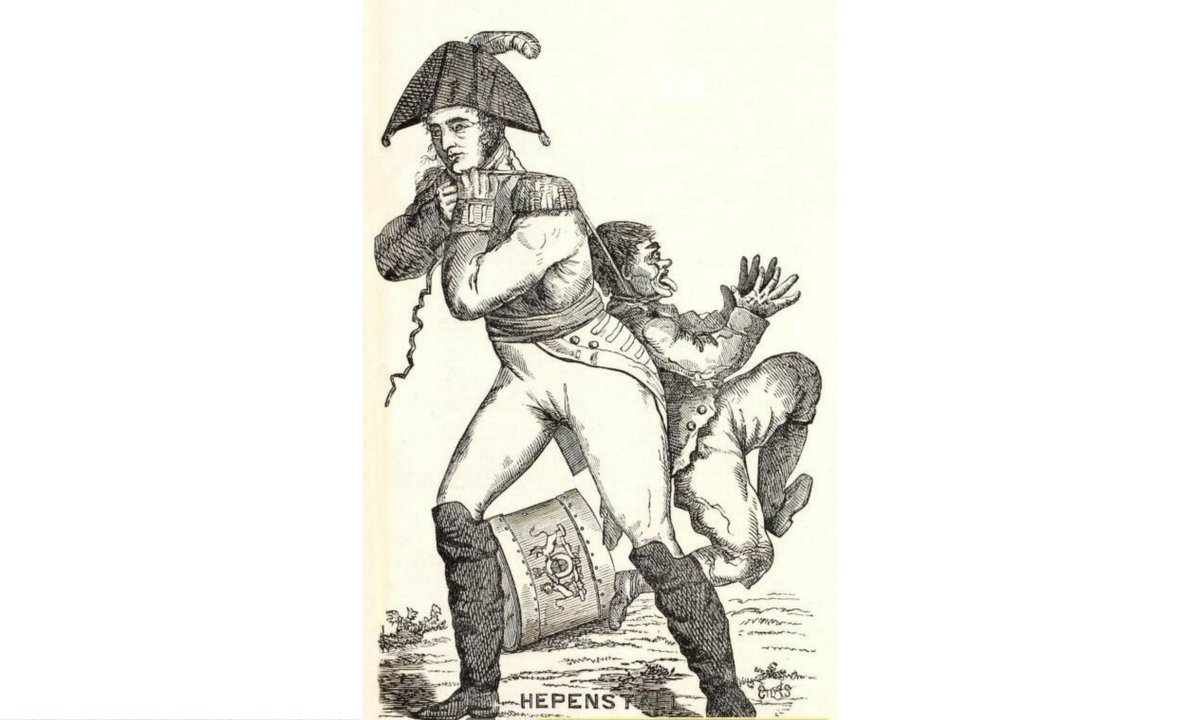

Some of the most infamous stories surround Lieutenant Edward Hepenstall, a giant of a man popularly known as The Walking Gallows for his habit of acting as judge, jury, and executioner, hanging men with his own cravat across his broad back as they kicked and choked to death.

Hepenstall was also fond of “half-hanging” which was where a noose would be thrown over a tree branch, and the victim would be hoisted in the air and strangled partially being dropped to the ground and interrogated – a Georgian version of waterboarding, I suppose. Grim stuff!

Second, the rural leaders of the United Irishmen were unconvinced about Robert Emmet – the Dublin leader of the 1803 Rising, just 24 years old at the time. A chief point of contention, aside from his inexperience, was the lack of arms — a big reason for defeat in 1798.

Robert Emmet hoped to win their support eventually by covertly manufacturing the arms he needed. And those who wouldn’t be swayed by that would rise up, he estimated, when the symbol of British power in Ireland, Dublin Castle, fell into his hands.

Which was another reason he chose Thomas Street as his base of operations. It was an industrialized area, home to numerous breweries and distilleries, where the manufacture of large numbers of pikes and munitions could go unnoticed. And almost did.

But while Emmet was still trying to convince various potential allies of the seriousness of his plot, and the extensiveness of his preparations, disaster struck. On 16 July 1803, an explosion at the covert arms factory on Patrick Street threatened to expose the entire plot.

Fearing imminent arrest, Emmet brought forward the date for the rebellion, despite not being quite ready, nor having firm commitments from potential allies. It was an impossible bind but he decided to try, and risk failure, rather than waiting and maybe getting caught anyway.

The date for the rebellion was set: 23 July 1803, just one week later. Which left no time for negotiation with rural leaders or to make further pleas for French help. Word was sent out that the people were to rise. All Emmet could do was hope. #onthisday

What actually happened on the day itself – 23 July 1803 – is commonly misunderstand. It’s often spoken of as a fool’s errand or some sort of shambles. In reality, Emmet had an intricate plan to take control of Dublin, and then the rest of the country.

In fact, recent scholarship shows that Robert Emmet's plan for 1803 later served as a template for the leaders of the 1916 Rising. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/markievicz-journal-suggests-link-between-1916-and-1803-1.2562517

The reason the plan was able to be recycled in this manner is because it was never executed in 1803. On the evening of the Rising, at around 9pm, Emmet ordered a solitary rocket to be fired into the air - a signal to his forces scattered around the city to stand down permanently.

A number of setbacks had left Emmet fearing a slaughter of the United Irishmen, and he was keen to avoid another 1798. However, this retreat allowed the British to portray the Rising as little more than a poorly attended drunken riot on Thomas Street.

In fact, this was a bit of propaganda, mostly aimed at the French... which is now commonly believed. The truth is that Robert Emmet came very close to succeeding, closer than he ever knew. (More to come in a bit!)

Thomas Street was of great strategic importance to Emmet’s plan. It was a densely populated area with many narrow laneways where men and tools and weapons could be hidden, and the main artery between Dublin Castle and the British Army HQ at Kilmainham.

I wandered up that narrow laneway to find these horses hanging out, showing how all kinds of industry could be taking place just off this busy city street, without passers by being aware at all.

And the men and tools and weapons were indeed lying in wait 215 years ago: 7000 pikes were stashed in a secret depot just off Thomas Street which were to be distributed near Cornmarket, close to Christchurch and Dublin Castle.

Large numbers of men were waiting in various safe houses around the south of the city, as well as in various United Irish pubs along Thomas Street itself like the White Bull and the Golden Bottle.

And then even more forces were hidden at various strategic locations like Wood Quay, Townsend Street, and Smithfield, ready to seize various arm depots and barracks, and prevent reinforcement of Dublin Castle. https://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th-century-history/the-rising-of-1803-in-dublin/

As Thomas Street was generally heaving on a Saturday, lined with pubs which were packed with farmers enjoying themselves after making some coin in the city markets; a sudden influx of people wouldn’t arouse immediate suspicion.

But things started to go wrong for the rebels almost immediately. They had huge stores of ammunition, but few guns to fire them with. The person tasked with acquiring the weapons that day absconded with the money. Uh oh.

Once the word spread that Emmet had failed to acquire the promised guns, support started to waiver. Some of the lower ranking United Irishmen hidden in the many pubs of Thomas Street decided the day would be more profitably spent drinking.

Again, remember that one of the key reasons for failure in 1798 was a lack of arms. Many of these guys were veterans of that conflict who refused to fight again unless they had weapons to match the British.

Emmet and his most trusted lieutenants had to spend the day racing from safe house to safe house to reassure the higher ranking rebels tasked with taking over those barracks and arm depots, and the Castle itself, that the Rising was going ahead regardless.

Another blow came when the rebels moving in from Kildare were turned back – told that the Rising was postponed and would be taking place the following weekend. Perhaps there was some miscommunication, but perhaps this was a saboteur in the pay of the British.

Together with Emmet’s failure to convince John O’Dwyer and his Wicklow-based band of hardened rebels to join the Rising – who had amazingly avoided British capture since 1798 – this would leave the United Irishmen very shorthanded indeed.

The final, fatal blow to Emmet's plans surrounded an industrious chap called Henry Howley, master of the arms store, who had cleverly manufactured hollow logs to surreptitiously carry pikes throughout the city.

Howley - a veteran of 1798 - also oversaw the manufacture of grappling irons and scaling ladders and even rudimentary rockets. https://comeheretome.com/2016/06/16/robert-emmet-and-the-munitions-depot-of-marshalsea-lane/

However, his role on the day of the Rising itself was to bring up a fleet of coaches which Emmet was going to use to attack Dublin Castle at speed - essential to the plan's success, in Emmet's eyes.

Disaster struck once more as the desperately unlucky rebel leader received some very bad news: Howley had been involved in an altercation and shot a British Colonel, and was forced to abandon the coaches and flee.

Emmet decided at this point to abort the rebellion. He felt a deep responsibility for the men under his command, and resolved to do everything he could to spare as many of their lives as possible.

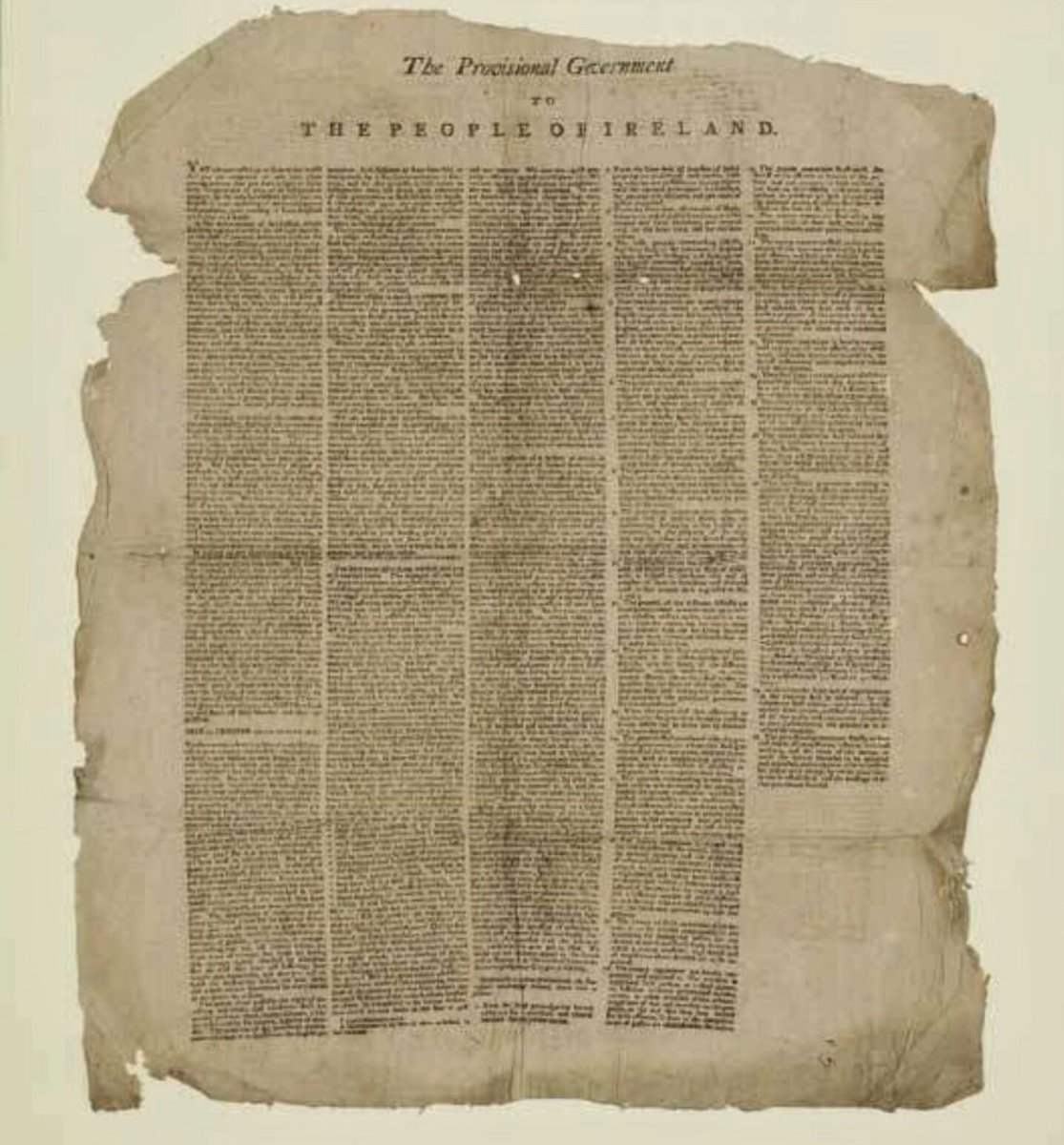

After sending up a single signal rocket just after 9pm, ordering all forces to stand down, Emmet left his arms depot at the head of a few hundred men and read his Proclamation of Independence.

It’s quite a remarkable document that doesn’t get anything like the same attention as the 1916 Proclamation, including radical provisions for the seizure of all Church property and the redistribution of land. https://www.failteromhat.com/declare1803.php

Anyway, after reading the Proclamation, Emmet headed towards Dublin Castle with a few hundred men, deliberately making significant noise to attract as much attention as possible. His aim was to create a diversion to allow his larger body of concealed troops to escape the city.

And they did, for the most part, bar some forces around the Coombe which engaged in heavy fighting with the British. Emmet managed to escape himself, with his men mostly intact, into the Wicklow Mountains which had helped John O’Dwyer foil the British so well for five years.

The tragedy for Emmet (and Ireland) was that the Castle was so lightly defended that he probably could have taken it fairly easily if he had pressed on. Who knows what would have happened then?

Robert Emmet didn’t survive on the run quite as long as John O’Dwyer. He honorably refused to escape to Paris (and still held out some probably unrealistic hope that the French would make good on their invasion promises). This honor was to be the undoing of him.

He moved from the safety of the Wicklow Mountains to a higher risk location in Dublin – Harold’s Cross – to be close to his sweetheart, Sarah Curran. Emmet was captured on August 25th and taken to Dublin Castle for questioning.

Many more rebels were interred in Kilmainham Gaol, having been swept up the night of the Rising and in subsequent days as the British turned the city upside down. With Emmet captured, the hangings could now begin. (More in a couple of hours!)

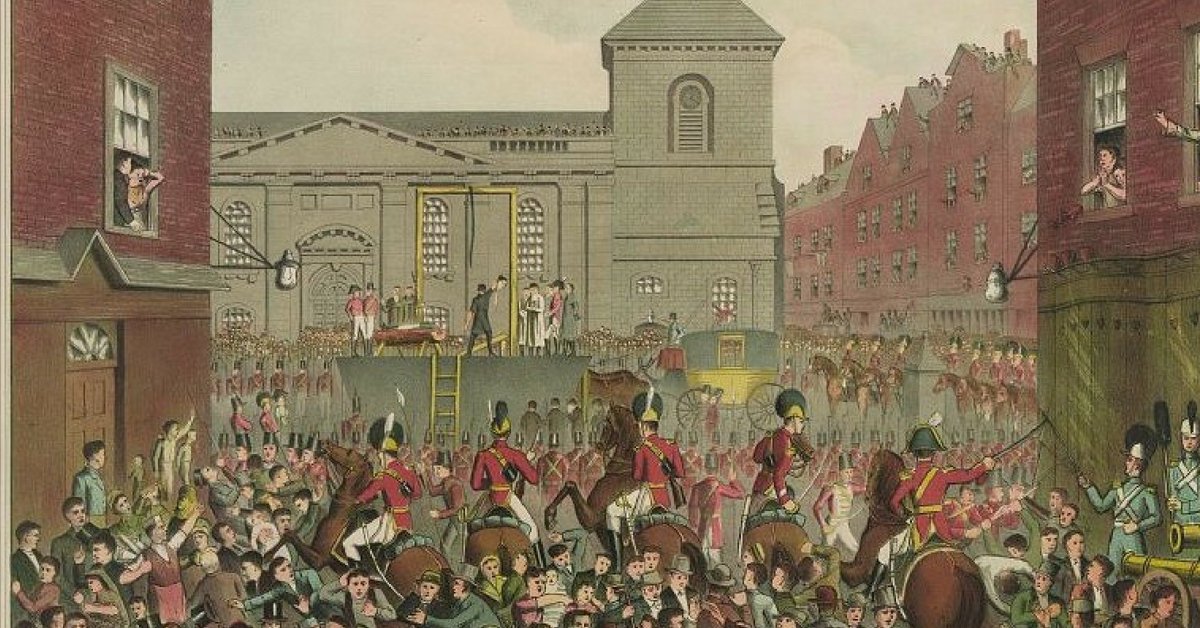

OK, I'm back! Let's talk about the hangings, because this was pretty crazy. They didn't take place at a jail or any of the normal city gallows. But right here, in the middle of Thomas Street, outside St. Catherine's Church.

Right in the middle of the street too! Lucky it was pretty wide. Plenty of room for a gallows. It was too see a lot of use over the next three weeks. But why did the British hang them here?

It seems the point was intimidation as well as retribution. Of the 20-30 men that were hung after the 1803 Rising, they were all executed where they lived or worked. One priest was even hung from the burned out rafters of his own house.

The timetable seemed calculated for maximum effect on the local population too. One man would be tried on one day at the Green Street courthouse near Smithfield, and he'd be executed the very next day on Thomas Street.

The legal proceedings themselves were self-congratulatory show trials, with the establishment keen to stress how just they were being, when in reality the barrister for the defense was a British spy - Leonard McNally. https://www.historyireland.com/volume-23/leonard-macnally-the-most-disreputable-barrister-to-have-ever-practised-at-the-irish-bar/

It seemed like Dublin Castle was trying to ratchet up the pressure each day, hoping one of the United Irishmen would turn King's Evidence and expose the whole plot, and identify those who hadn't been apprehended yet.

It's a little difficult to be definitive about who was executed in this manner (and how many), in part because the records are a bit of a muddle, and there were a couple of cases of probable mistaken identity - including one particularly tragic case.

However, as far as I can tell, these men were hung in the 3 weeks leading up to Robert Emmet's trial, or just shortly after (mostly on Thomas Street, but some others elsewhere):

Edward Kearney, Thomas Maxwell Roach, Owen Kirwan, James Byrne, John Biggs, Denis Lambert Redmond, Felix Rourke, John Killen, John McCann, Thomas Donnelly, Laurence Begley, Nicholas Tyrell, Michael Kelly, John Hay, Henry Howley, John McIntosh, and Thomas Keenan.

When the day rolled around for the trial of the rebel leader, Robert Emmet, tensions in the city were pretty high. On all sides, because as a Protestant from a well-to-do family, Robert Emmet was seen by Dublin Castle as one of their own. Which made him even more of a traitor.

This is one of the reasons I was so fascinated with the 1803 Rising, and why it's so tragic that it failed - it was pretty much the last time Protestants and Catholics came together to fight the British.

After the failure of 1803, the republican movement would get much more sectarian... and ruthless. The course of Irish history, and Northern Ireland in particular, could have been very different.

The trial of Robert Emmet would soon go down in history. The British had already ensured they would get their intended result: aside from having turned his barrister into an informer they blackmailed Emmet into not mounting any defence, darkly hinting of harm towards his fiancée.

Nevertheless, the British had a show to put on, desperate to give the appearance of justice to a watching world, and the trial lasted for 12 hours. Before sentence was pronounced, Robert Emmet was permitted to address the court. They would soon regret this.

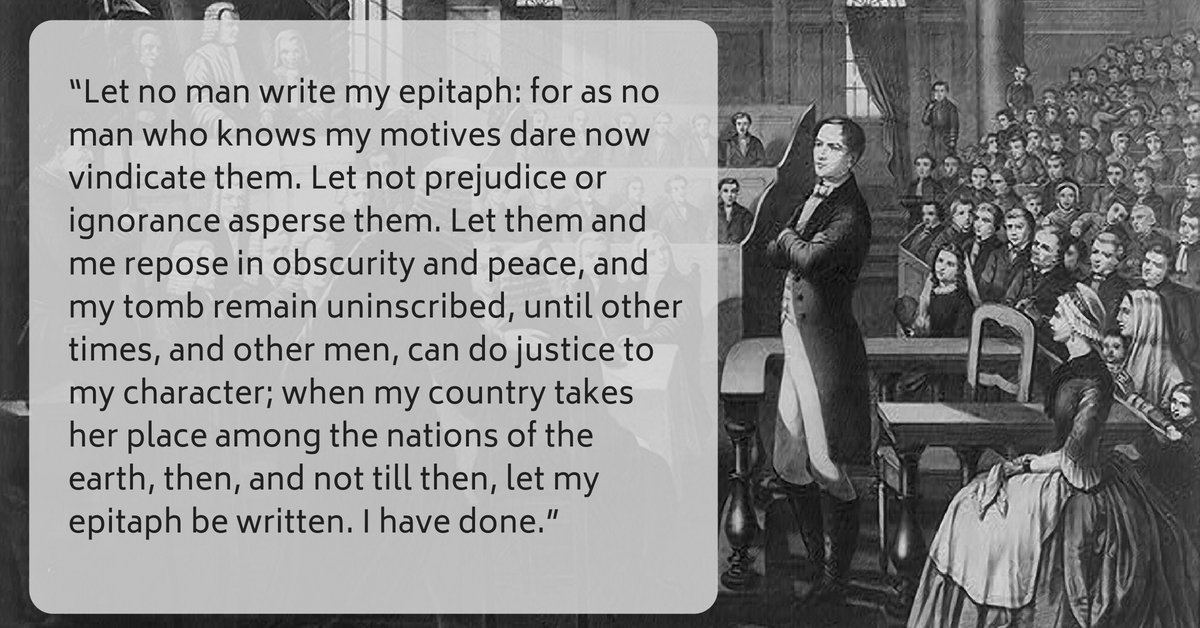

Robert Emmet's speech from the dock is now famous, and served as a rallying cry for Irish republicans for generations afterwards. The exact contents are disputed, as both sides raced to the printers to issue their own versions.

Where Emmet's supporters are alleged to have prettied up his speech so that his already impressive eloquence reaches near superhuman levels, the British had a different audience in mind, and are alleged to have strategically inserted remarks which were less friendly to the French

Whatever the exact truth of the matter, the level of eloquence displayed by Robert Emmet, after spending 12 hours or so on his feet, manacled to the dock, are remarkable. The whole speech is worth reading, but the closing lines are most famous.

What makes it even more remarkable is that the imposing judge presiding on that day - Lord Norbury - attempted to shout him down several times during the ten or so minutes which he spoke, but Emmet was resolute, and insisted on having his say.

This was to cost him, however. When Norbury finally regained control of his courtroom, he pronounced the typical sentence of being "hung, drawn, and quartered" but specifically insisted the latter parts were carried out, which was usually just a bit of vocal theater.

But, for Emmet at least, the full grim spectacle would take place. Right on Thomas Street.

The City Executioner was a man by the name of Tom Galvin. Now, Galvin had hung many men, but he'd never beheaded one. He had to borrow a butcher's block and long handled knife from a butcher in Smithfield and hoped that would do the job.

By the time Emmet was finally brought to Thomas Street - the authorities taking him the long way through packed streets for maximum impact - the streets were heaving with tens of thousands of people.

Rumors abounded that John O'Dwyer - whose reputation had reached near mythic status at this point - was planning a daring rescue.

Indeed, at one point a clatter of hooves were heard as Emmet put his head in the noose, and hope flickered across his face. Cruelly dashed - it was British reinforcements from Kilmainham, concerned at the riotous atmosphere.

There was to be no heroic escape for Emmet. He was hung, and then Tom Galvin attempted to behead him, first sawing at the base of his head with the long butcher's knife, and then eventually resorting to an axe. It took thirty minutes.

Most disturbingly, when Galvin severed a major artery there was a giant spurt of blood, indicating that Emmet was possibly still alive at this point.

Galvin took Emmet's severed head and walked to the front of the stage, booming out "THIS IS THE HEAD OF A TRAITOR." Blood trickled off the stage and was lapped from the cobbles by hungry dogs.

Emmet's body was taken to the pauper's graveyard at Kilmainham as his friends and family were afraid to come forward and claim it. That night, his body was dug up and spirited away. To where? Nobody knows for sure.

I was so captivated by this story that I wrote a novel set during these weeks leading up to Robert Emmet's trial. It focuses on the (fictional) story of a market trader, whose patch is taken over by this gallows. You can check it out here: http://davidgaughran.com/books/liberty-boy/

The Rising of 1803 and the tumultous months which followed form the historical backdrop to the plot. And it was researching this that I discovered the Rising wasn't the shambles it was popularly depicted as.

There's no doubt it would have seen a much greater loss of life if Emmet hadn't ordered his men to stand down that evening, and it's much more influential than popularly believed.

It also marks a turning point for Irish republicanism, which would switch from engaging the better armed and trained British troops in open battle, and instead focus on close quarters city fighting for which they weren't trained, or guerrilla actions.

That's it! I hope you enjoyed this little curious bit of Irish history that happened #onthisday. If you want some (actual) historian recommendations Ruan O'Donnell's book "Robert Emmet and the Rising of 1803" is brilliant: https://amzn.to/2LCZI29

Finally, I have to give a shout out to the best blog out there on Dublin history @chtmdublin which covers local/forgotten Dublin history in the most fascinating and entertaining manner. Check it out: https://comeheretome.com/

/end

/end

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter